Ironically, the most widely celebrated holiday in the Islamic Republic of Iran long predates the official religion. Nowruz, literally “New Day” in Farsi, marks the first day of spring and the Persian New Year. The holiday, which usually falls on or around March 21, is widely celebrated across the Middle East and Central Asia.

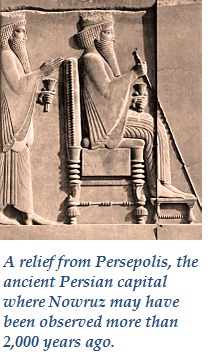

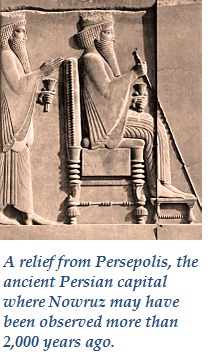

Nowruz is a national holiday celebrated by Iranians of virtually all ethnicities and religions. Celebrations may date back to Cyrus the Great’s reign in the sixth century B.C. Many of the season’s traditions have roots in Zoroastrianism, an ancient monotheistic faith still practiced by some

25,000 in Iran.

Shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, some hardliners unsuccessfully tried to

suppress the holiday due to its pre-Islamic origins. But Iran has never severed connections to its pre-Islamic past. “Iran’s advancements after Islam are incomparable to its past. However, pre-Islamic history of Iran is also part of our history,” Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

said in 2008. Most Iranians still look to the ancient Persian Empire as a source of pride.

The following is an overview of traditions associated with Nowruz.

A Persian Santa Claus and Troubadour

Amoo, or “Uncle,” Nowruz, and his sidekick Haji Piruz are folk characters who herald the spring. Uncle Nowruz, like Santa Claus, hands out presents to children and is an older man with a white beard.

Haji Piruz, his clownish assistant, sings joyous songs and plays a tambourine or drum in city streets and squares. Men and boys blacken their faces with soot, and wear bright red clothing and a conical hat to portray the character in hopes of earning some coins for providing entertainment. The following is a translation of one common song associated with Haji Piruz:

Wind and rain have gone.

Lord Nowurz has come.

Friends, convey this message.

The New Year has come again

This spring be your good luck

The tulip fields be your joy.

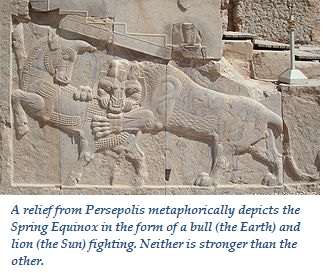

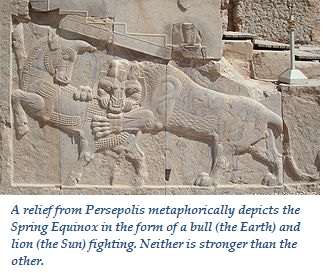

Nowruz is celebrated on the Spring Equinox, but the holiday includes many stages and weeks of preparation.

Spring Cleaning

Iranians begin preparing their homes for Nowrouz weeks in advance. The annual spring cleaning is known in Farsi as khoneh takooni, or “shaking the house.” Families meticulously wash rugs, windows, curtains and repair furniture. They throw out or donate old household goods and purchase new clothing to greet the coming spring.

Haft Seen Table

One of the most important Nowruz

traditions is setting the haft seen table, which includes seven symbolic items all starting the with an “s” sound:

• Sabzeh (sprouted wheat grass): For rebirth and renewal

• Samanu (sweet pudding): For affluence and fertility

• Senjed (sweet, dried lotus tree fruit): For love

• Serkeh (vinegar): For patience and wisdom gained through aging

• Sir (garlic): For medicine and maintaining good health

• Sib (apples): For health and beauty

• Sumac (crushed spice made from reddish berries): For recalling the sunrise

Additional items on the table include:

• Mirror: To reflect on the past year

• Live goldfish in a bowl: To represent new life

• Orange in a bowl of water: To symbolize the Earth

• Decorated eggs: For fertility

• Coins: For future prosperity

• Books of classical poetry and/or the Koran: For spirituality

Fire Jumping

On the last Wednesday of the year, Iranians set up bonfires in public places and leap over the flames in a ritual, Chahar Shanbeh Soori, thought to ensure good health for the year. People sing the following song addressing the fire while jumping:

Give me your beautiful red color

And take back my sickly pallor!

Since the 1979 revolution, hardliner clerics and public officials have warned against observing the ritual, citing safety hazards and roots in pre-Islamic traditions. In recent years, youth have begun using firecrackers and other fireworks.

On March 1, 2015, the head of Tehran’s police prevention unit

said authorities would take legal action against people blocking the main streets or bothering others with bonfires. On March 13, Tehran’s interim Friday prayer leader and Assembly of Experts member Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami

said the ritual is

haram (forbidden) from a religious perspective and reminded the public that many festivals have turned into days of mourning because of unfortunate accidents.

On March 18, 2015, nearly 400 people were reportedly

injured and three died in accidents related to the ritual. In 2017, 10 people died and more than 2,000 people were

injured, according to the head of Iran’s Center for Emergency Medical Services.

Food

For

Chahar Shanbeh Soori, some Iranians make wishes and distribute a special soup consisting of roasted garbanzo beans, almonds, pistachios, hazelnuts and dried figs, apricots and raisins.

Another

soup,

Ash-e-reshteh (left), is traditionally served around Nowrouz. The hearty mixture is filled with noodles and multiple types of beans. The noodle knots represent the many possibilities for the coming year, and untangling them is thought to bring good fortune.

Sabzi pollo mahi, is a common fish and rice dish served during Nowrouz. The rice is mixed with green herbs to symbolize the coming spring.

Several types of sweets are also ubiquitous at this time of year.

• Baqlava: flaky pastry sweetened with rosewater

• Naan bereng: cookies made from rice flour

• Noghl: sugar-coated almonds

• Samanu: a sweet pudding made from sprouted wheat

Many Iranians have found these foods and other items increasingly expensive since 2012. Tightened international sanctions imposed over Tehran’s controversial nuclear program have dramatically raised prices. “I didn’t buy nuts last year, because prices were very high and I won’t buy them this year either,” a 37-year-old mother of two told

The National in 2014.

The Count Down

After

Chahar Shanbeh Soori, Iranians wait with their families and friends for the exact moment when the vernal equinox occurs,

Tahvil in Farsi. Elders distribute sweets and children receive coins. People begin making short visits to the homes of friends and family throughout the day and night. At each house visit, hosts provide nuts, sweets, dried fruits and tea to their guests.

Sizdah Bedar

On the 13th day of the new year, Iranians try to get rid of the bad luck associated with the number 13 by spending the day outside having fun with family and friends. Many people pack picnic lunches and head to parks or the countryside. The tradition is known as sizdah bedar, or “getting rid of the 13th.”

Iranians also discard the sabzeh grass from the Haft Seen table, which collected all the potential bad fortune of a family during Nowruz. Some unmarried girls knot grass blades symbolizing the union of a man and woman in hopes of finding a husband before the next Nowruz.

The United Nations includes Nowruz on its List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Click here for more information.

*A previous version of this article was published in 2014.

Photo credits: Persepolis by alisamii (http://www.flickr.com/photos/alisamii/4806644274) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Haji Firuz and Haft Seen Table by Robin Wright, Fire jumping by PersianDutchNetwork (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Ash-e-Reshteh by AilinParsa (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Amoo, or “Uncle,” Nowruz, and his sidekick Haji Piruz are folk characters who herald the spring. Uncle Nowruz, like Santa Claus, hands out presents to children and is an older man with a white beard. Haji Piruz, his clownish assistant, sings joyous songs and plays a tambourine or drum in city streets and squares. Men and boys blacken their faces with soot, and wear bright red clothing and a conical hat to portray the character in hopes of earning some coins for providing entertainment. The following is a translation of one common song associated with Haji Piruz:

Amoo, or “Uncle,” Nowruz, and his sidekick Haji Piruz are folk characters who herald the spring. Uncle Nowruz, like Santa Claus, hands out presents to children and is an older man with a white beard. Haji Piruz, his clownish assistant, sings joyous songs and plays a tambourine or drum in city streets and squares. Men and boys blacken their faces with soot, and wear bright red clothing and a conical hat to portray the character in hopes of earning some coins for providing entertainment. The following is a translation of one common song associated with Haji Piruz: For Chahar Shanbeh Soori, some Iranians make wishes and distribute a special soup consisting of roasted garbanzo beans, almonds, pistachios, hazelnuts and dried figs, apricots and raisins.

For Chahar Shanbeh Soori, some Iranians make wishes and distribute a special soup consisting of roasted garbanzo beans, almonds, pistachios, hazelnuts and dried figs, apricots and raisins. After Chahar Shanbeh Soori, Iranians wait with their families and friends for the exact moment when the vernal equinox occurs, Tahvil in Farsi. Elders distribute sweets and children receive coins. People begin making short visits to the homes of friends and family throughout the day and night. At each house visit, hosts provide nuts, sweets, dried fruits and tea to their guests.

After Chahar Shanbeh Soori, Iranians wait with their families and friends for the exact moment when the vernal equinox occurs, Tahvil in Farsi. Elders distribute sweets and children receive coins. People begin making short visits to the homes of friends and family throughout the day and night. At each house visit, hosts provide nuts, sweets, dried fruits and tea to their guests.