Kenneth Katzman, a former CIA analyst and lead Iran specialist at the Congressional Research Service, is now a senior advisor at the Soufan Group.

What does Iran want from its intelligence agencies? What are their primary objectives?

The primary mission of Iran’s intelligence agencies is to keep the Islamic regime in power. The Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Intelligence Organization are the main intelligence agencies. Their missions overlap extensively because their agendas are broad. Ascertaining their day-to-day operations is difficult from thousands of miles away and without a U.S. embassy in Tehran. But much of their work involves repressing dissidents at home and abroad. They are especially concerned with stifling organized opposition.

Much like U.S. intelligence, Iranian intelligence gathers information on other governments, especially in the Middle East. Tehran wants to find out what rivals are planning and discern the effectiveness of its policies.

Additionally, the agencies look for materials and components for producing arms, especially missiles and drones. The MOIS has agents based in Iranian embassies across Europe. As civilians, MOIS personnel can blend in better than IRGC personnel, who are military people. MOIS agents look for technology from foreign companies—including German, French, Italian and Swiss firms—and for holes in international sanctions to procure technology. IRGC intelligence also engages in procurement, but mostly in coordination with the MOIS.

Who or what do the agencies track? Who or what are their targets?

In Europe and abroad, the agencies track dissidents in exile, some of whom have networks in Iran that agitate against the government. Intelligence agencies have targeted a broad range of exiled oppositionists, including monarchists, Kurdish separatist groups, dissidents who defected from the Islamic regime, and the Mujahedeen-e Khalq (MEK), a left-wing Islamist organization. They have also targeted individual activists and journalists, especially those involved in the Green Movement protests over the disputed 2009 presidential election as well as several subsequent rounds of unrest.

In Iran, agencies have a wide range of targets, from underground organizations to government employees suspected of opposing the regime. Dissent is widespread in Iran, but the agencies do not attempt to track every citizen. They tend to focus on organizations and networks, especially ones actively recruiting members and plotting against the government.

The agencies are particularly concerned about Arab, Kurdish and Baluch separatist groups. The ethnic minorities have long alleged neglect and discrimination by the Persian-dominated central government. Intelligence agencies also focus on labor unions, oil workers and bazaaris, or traditional merchants—groups that played a key role in fueling the 1979 revolution against the monarchy.

How do they track their targets? What tactics are the intelligence agencies known to use—and use most effectively?

The agencies employ diverse tactics. They glean a lot of information from online activities. For example, the IRGC has a special cyberspace division. Agencies intercept electronic messages and scrub social media for criticism of the government. They also use traditional collection methods, including interrogations, wiretapping and trailing people. Agents often interview family, friends and co-workers of suspects. Sometimes, they lure exiled dissidents to countries neighboring Iran to be apprehended by Tehran’s agents.

The agencies employ diverse tactics. They glean a lot of information from online activities. For example, the IRGC has a special cyberspace division. Agencies intercept electronic messages and scrub social media for criticism of the government. They also use traditional collection methods, including interrogations, wiretapping and trailing people. Agents often interview family, friends and co-workers of suspects. Sometimes, they lure exiled dissidents to countries neighboring Iran to be apprehended by Tehran’s agents.

The MOIS has a reputation for using more subtle methods than the IRGC. MOIS agents might use fake identities to infiltrate a company and root out dissidents, whereas IRGC operatives are known for more kinetic action, such as breaking into warehouses or scouting locations. IRGC agents, who are military people, more readily employ force to repress dissent.

What roles have the different agencies played in Iran and abroad? What impact have they had?

The MOIS has been more methodical and deliberative than IRGC intelligence. It conducts research and circulates reports. The MOIS might, for example, produce an assessment on Iranian policy in Iraq and provide recommendations. The MOIS has historically focused on Europe, where many Iranian dissidents have sought refuge.

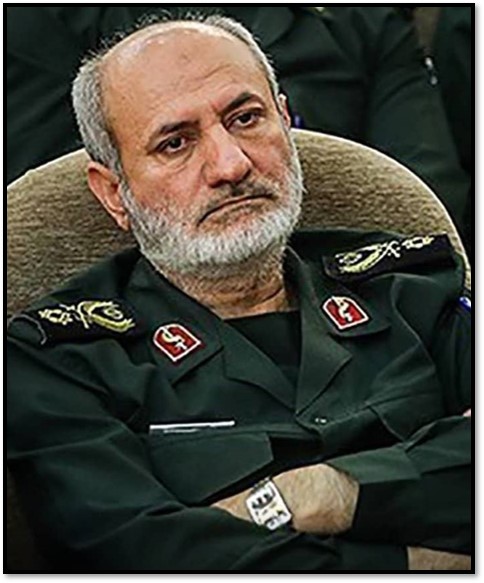

In contrast, IRGC intelligence has historically focused on Iran and the surrounding region, where most armed opposition groups operate. IRGC intelligence deploys alongside the Qods Force, the elite branch responsible for IRGC operations abroad. The Qods Force manages the arming, training and funding of proxy militias, including Hezbollah in Lebanon, Shiite groups in Iraq, and the Houthis in Yemen. IRGC intelligence helps plot routes and logistics to move weapons, money and personnel across the Middle East.

Inside Iran, the MOIS and IRGC intelligence play similar roles. Both agencies look to develop information on networks and underground groups. But IRGC intelligence has focused particularly on preventing armed attacks in Iran, such as bombings or the storming of government buildings.

Their impact is difficult to measure, but both organizations have been critical to keeping the regime in power. The Islamic Republic has weathered four rounds of major protests since the 2009 Green Movement. Intelligence agencies, along with law enforcement, quashed the demonstrations. IRGC intelligence confronts near-term, tangible threats to the regime. Some MOIS operations appear to have less impact. The MOIS has assassinated dissidents but often people who did not have much support inside Iran. The targets reflect the government’s paranoia about anyone who challenges the theocracy.

Are there famous cases of Iranian intelligence operations that illustrate what the agencies do, and how they differ?

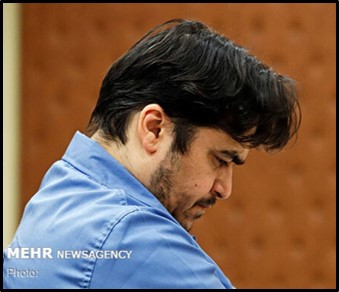

In October 2019, IRGC intelligence lured dissident journalist Ruhollah Zam to Najaf, Iraq. Zam ran Amad News, an anti-government website, from France. A woman reportedly promised Zam money to launch an opposition television station and invited him to Iraq to collect the cash. The details are murky, but IRGC intelligence kidnapped Zam and brought him back to Iran to face trial. He was accused of fueling protests and was hanged in 2020.

Intelligence agencies have also assassinated people. The MOIS has been linked to several plots in Europe. Shapour Bakhtiar, the last prime minister before the revolution, was killed in his Paris home in 1991. Two of the three assailants reportedly had MOIS ties.

But intelligence agencies have failed to prevent attacks by Iran’s adversaries. Israel alone has allegedly conducted at least two dozen operations against the nuclear and drone programs since 2010. Israeli agents reportedly assassinated Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the father of Iran’s nuclear program, in 2020, representing a huge intelligence failure. Israel was also linked to explosions at the Natanz nuclear site, where Iran enriches uranium, in 2020 and 2021.

Who do the agencies report to? How would you diagram the chain of command?

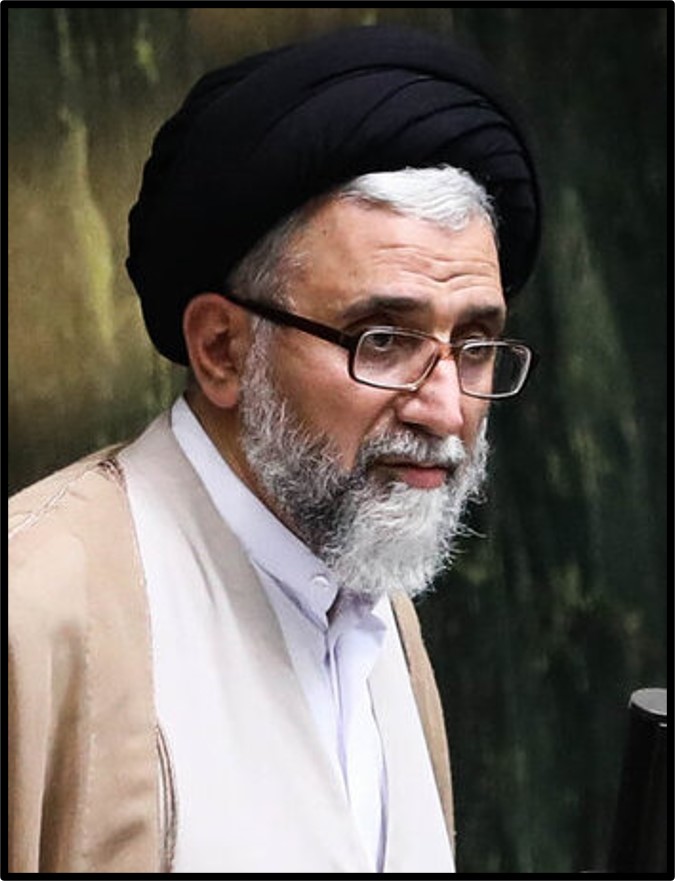

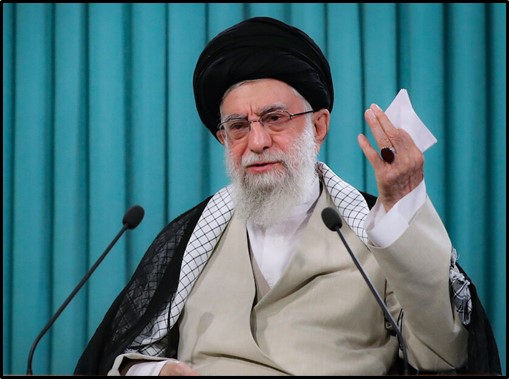

Mapping the chain of command is difficult. The supreme leader is the highest authority, but he does not micromanage day-to-day intelligence activities. The MOIS chief holds a cabinet position and reports primarily to the president, who can remove the minister with the supreme leader’s approval. IRGC intelligence, however, falls under the military chain of command and answers to the supreme leader. The president would not normally get involved in removing an IRGC intelligence chief.

How do the theocracy’s intelligence apparatuses differ from the monarchy’s intelligence agencies? How are they similar?

Since the 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic has set up more than a dozen intelligence agencies in addition to the MOIS. Some have overlapping missions and compete for resources. Both branches of the armed forces, the IRGC and the conventional military (Artesh), have their own intelligence organizations.

Intelligence collection was much more centralized under the monarchy. The shah had one main intelligence organization, the SAVAK, the predecessor of the MOIS. The military, despite being well-funded, did not have a well-developed intelligence apparatus.

How do Iran’s intelligence agencies differ from U.S. intelligence? How are they similar?

One major difference is that the United States does not have an equivalent to the IRGC or its intelligence organization. Also, U.S. laws prevent intelligence agencies from spying on Americans at will. Iran lacks a strong distinction between civilian and military intelligence, so some agencies can spy on both foreign adversaries and Iranian citizens with few constraints. The IRGC represses domestic dissent despite being a military force. The U.S. military does not surveil U.S. citizens or conduct riot control.

Some U.S. and Iranian agencies are similar. The MOIS functions like a combined FBI and CIA in that it has both domestic and international investigative powers. The intelligence arm of the Artesh is similar to the Defense Intelligence Agency. Artesh intelligence assesses foreign militaries and strategic threats to Iran, such as U.S. and Saudi military capabilities. Like the U.S. military, Artesh intelligence tries to avoid political issues. Its primary mission is to protect Iran from foreign militaries, not suppress demonstrations.

In the United States, large police forces, such as the New York Police Department, have their own intelligence units. The Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) is Iran’s national police. LEF intelligence focuses on typical policing issues, including smuggling, money laundering, robbery, prostitution and other crimes. The United States and Iran also have similar counterintelligence bodies in many agencies that are designed to ensure that rules are followed and classified information is used properly. In Iran, counterintelligence agencies are responsible for preventing infiltration. They investigate their own people and review their own apparatus.

Is there a hierarchy among Iran’s intelligence agencies? Which are the most powerful? Why?

The MOIS and IRGC intelligence are the most important agencies, but the IRGC is the more powerful of the two. Parliament has much less oversight over the IRGC, which reports to the supreme leader. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei rarely acknowledges mistakes or internal problems. IRGC intelligence mistakes are often blamed on other agencies. The MOIS chief, meanwhile, can be removed much more easily. There has been more turnover in the minister position. The MOIS chief also receives more criticism from lawmakers.

What are the relations among the agencies? How do they compete or work together? Are there rivalries?

The agencies may jostle for power on a case-by-case basis, but there is not systematic competition. The MOIS and IRGC intelligence have their own roles until there is a problem. Competition and cooperation depend on the issue. The MOIS might investigate a dissident network in Europe, which would be outside the purview of IRGC intelligence. Agencies might develop a source that another organization detains, which can cause problems. But that happens in the United States as well.

The MOIS and IRGC intelligence rivalry was evident in their analysis of Iranian policy toward Iraq in 2010 and 2011. Iran had emerged as the most influential foreign power in Iraq following the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. The IRGC supported Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki (2006-2014), a Shiite who repressed the Sunni minority. The IRGC empowered Shiites who monopolized Iraq’s political system and marginalized Sunnis. The MOIS warned that the IRGC’s actions were counterproductive to Iran’s interests. The ministry found that Maliki’s policies were pushing some Sunnis to join radical militant groups, which later became ISIS and threatened Iran.

The MOIS and IRGC intelligence, however, can cooperate and share resources. When an issue requires action from another agency, they share information. The MOIS will share intelligence if it can help the IRGC resolve a potentially public and embarrassing problem. IRGC intelligence might get involved if the MOIS gets a tip regarding a potential attack plot. The MOIS would report potential demonstrations, and the IRGC might deploy forces in response. The MOIS would relay who is involved in the demonstration, how large it might be, and other information. IRGC intelligence would then put down the demonstration.

How does the spectrum of intelligence agencies reflect the political spectrum in Iran?

The agencies do not reflect a political spectrum. The IRGC is run by hardliners. The MOIS also tends to be hardline, but some of its analysts are professionals who are more open to questioning government policies. Some ministers of intelligence and security have been less extreme than others, but not dramatically so. These agencies are generally led by solid supporters of the theocracy and the supreme leader. They do not reflect broader opinion in Iran.

How have the role or goals of Iran’s intelligence agencies differed under disparate reformist or hardline governments?

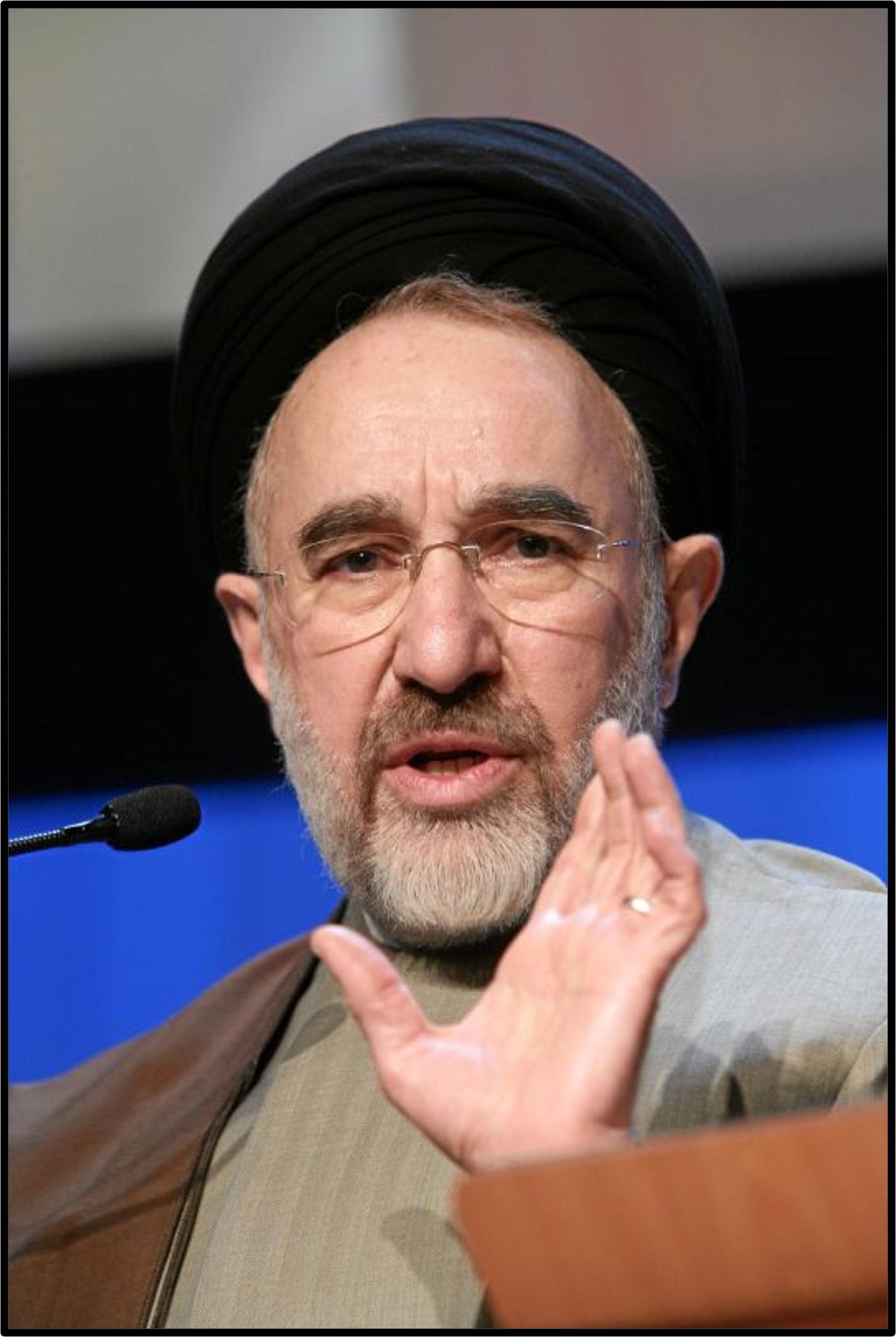

The role or goals of the agencies have not differed under presidents, whether reformist or hardliner. Agency leadership positions are slated for hardliners who do not hesitate to crush dissent. Even former President Mohammad Khatami, the most reformist president, was not able to effectively rein in the agencies. He was almost removed for not suppressing the student riots in 1999 fast enough. Khatami shifted to a harder line when his presidency was at risk.

Iran’s presidents have not been able to appoint anyone who was liberal and open to allowing more dissent. They have more discretion on other issues, including the economy, health affairs, education, culture and media. Regime survival depends on the intelligence and security positions. It depends on absolute loyalty to the official line and the supreme leader.