Hadi Semati is a former professor in the faculty of Law and Political Science at Tehran University and a former scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is now an independent analyst.

What were the key political events or developments in Iran in 2022?

The protests that erupted in September were the most significant domestic development of the year. They posed the greatest challenge to political stability since the 1979 revolution. The demonstrations were sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman detained by the morality police. But the essential driver was the dire economic situation, which also was a key factor in previous rounds of demonstrations. The 2017-2018 protests were over high prices of basic goods, such as eggs. And the 2019 demonstrations were triggered by an overnight gas price hike.

In 2022, a palpable sense of despair spread across socioeconomic classes, even to the political elite. Inflation surged to more than 50 percent by June. Some Iranians had initially been hopeful that the situation would improve because the United States and Iran were in talks about reviving the 2015 nuclear deal. When negotiations faltered in September, the prospects for economic relief from U.S. sanctions were dashed.

In September, members of Generation Z, who fueled the protests, were mobilized over issues of personal freedoms. They sought an end to state interference in their dress codes and other lifestyle issues. But deep down, I suspect that they were also expressing frustration about the lack of economic opportunity. Without decent jobs, many have been forced to postpone marriage and gaining independence from their parents. Many Iranians also long to travel but cannot afford to take vacations or relocate.

The protests extended to all 31 provinces over the last four months of 2022. But the turnouts did not mobilize large enough crowds or diverse enough sectors of society to pose an imminent danger to the regime. An estimated 200,000 people participated during that period. The lower and middle classes did not turn out in force. The individual demonstrations were small, sometimes just dozens or hundreds of people. In contrast, millions poured into the streets during the Green Movement protests over the disputed 2009 presidential election.

The government also did not appear to be using all the tools available to quash the demonstrations. More than 500 people were reportedly killed during the first three months, but the government had apparently learned from about the potential backlash from previous crackdowns and sought to avoid mass killings that could fuel wider resistance. It primarily deployed the police, the Law Enforcement Forces, and Basij paramilitary to disperse the demonstrations, but it appeared to be holding the elite Revolutionary Guards in reserve.

Authorities also used targeted methods to limit the internet by curtailing access in particular hotspots and during specific times of day. During the economic protests in 2019, the government had completely shut down the internet for 10 days nationwide in ways that which negatively impacted the economy.

What were the most important developments in Iran’s foreign policy in 2022?

On foreign policy, Iran took two transformative steps. First, it failed to agree to proposed terms to revive the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). After President withdrew from the deal in 2018, the Biden administration signaled intent to rejoin the pact. The world’s six major powers began new talks in Vienna—led by the European Union—in April 2021. Sporadic negotiations dragged on until August 2022, when Iran’s negotiating team returned from Vienna. The public mood shifted as many Iranians increasingly concluded that a deal was virtually if not official dead.

Second, Iran decided to arm Russia with drones for the war in Ukraine, reflecting the deeper relationship between Tehran and Moscow. Iran provided hundreds of drones in 2022—the Shahed 136 and the Mohajer 6 – and sent trainers to Russia and Crimea.

In December, the United States charged that Iran had become Russia’s “top military backer.” Moscow, in turn, offered military and technical support. The White House expressed concern that Russia might even provide Iran with Sukhoi Su-35ts, advanced fighters jets that would boost Iran’s aging air force. The White House also said that Moscow may have advised Tehran on how to put down the protests. Iranian officials thought that helping Moscow, as part of a shift to the East, will boost Tehran’s deterrence against Western powers.

There was still significant debate among the foreign and security policy elite, and the press as well, about the “dangers of the total shift towards the East” and its adverse effects for Iran’s national interests. However, one can argue that the United States, and the West in general, have some responsibility in pushing Iran further in that direction.

President Ebrahim Raisi marked 17 months in office at the end of 2022. What were his successes? What have been his failures?

Raisi made big promises but failed to deliver anything significant in his first full year in office. His poor performance was due largely to limited managerial experience. Raisi, a cleric, started his religious training after finishing elementary school. He spent his career in the judiciary and therefore lacked executive experience. Raisi’s cabinet was the most ill-equipped to take office of any previous group of senior officials. Many ministers lacked expertise relevant to their portfolios. Four of his picks were members of the Revolutionary Guards.

Raisi and his team severely underestimated the economic, political and social challenges facing Iran. When he took office, the economic situation was poor after years of U.S. sanctions, mismanagement and corruption. But the economy got worse on Raisi’s watch. By the end of 2022, the rial had lost some 44 percent of its value against the dollar since he took office in August 2021.

Raisi fell short of his four main goals on the economy, including:

- Fighting corruption

- Creating one million housing units annually

- Creating one million jobs annually

- Stabilizing prices and reducing inflation

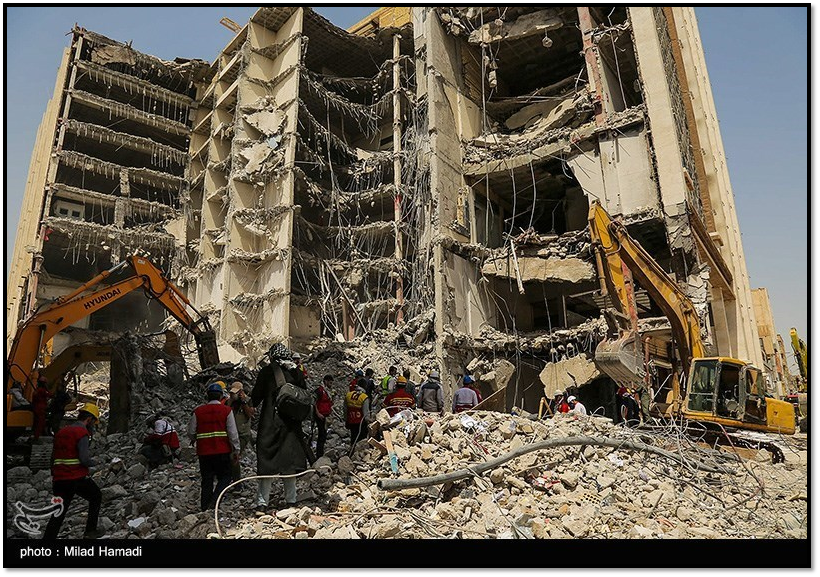

On corruption, Raisi had promised to continue a campaign he had started as head of Iran’s judiciary from 2019 to 2021. But a series of high-profile corruption cases during his first year in office undermined his credibility. In May 2022, the collapse of the Metropol, a 10-story residential and commercial building in Abadan, reflected the scope of corruption; 43 people were killed. Engineers had reportedly warned of faulty construction of the Metropol, but government inspectors failed to enforce building codes the owner of the building had strong political connections. After protests calling for government accountability, officials arrested more than a dozen people--including the Abadan mayor and two previous mayors--connected to the Metropol.

On housing, the government didn’t release figures in 2022 on how many units were built. But in December, the new minister of roads and urban development, Mehrdad Bazrpash, warned that the construction budget would need to be doubled to meet Raisi’s target of one million units annually.

On jobs, Raisi also fell short. Only 374,000 new jobs were created during his first year in office, according to government statistics. Meanwhile, about a half million new people entered the job market.

On prices, Raisi failed to curb inflation. The government resorted to printing more money to cover the budget deficit. As of November 2022, consumer prices were up 48 percent compared to 2021. The prices of food and beverages were up a staggering 68 percent compared to last year. Many Iranians cut back on staples, such as fruit and dairy.

What is the state of Iran politically? What’s different today from a year ago? How stable is the government given the protests over economic issues and personal freedoms in 2022?

The government was surprisingly stable. But cleavages emerged among conservatives or hardliners. They controlled all the major branches of power, including executive, legislative, parliamentary, economic and the military. But they did not reach a consensus on strategy to solve the myriad challenges that contributed to the protests. Some officials called for dialogue with demonstrators, while others called for a harsher crackdown. Elite infighting could increase further with the succession of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who turned 83 in 2022, looming down the road. Various factions were already jockeying to influence that process.

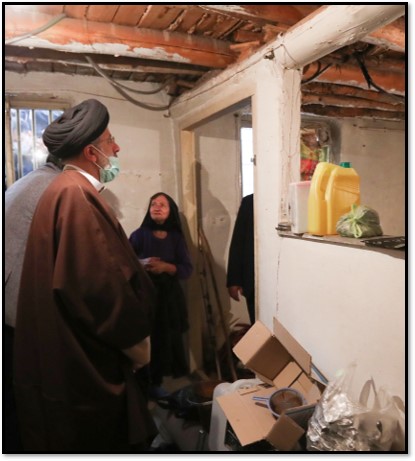

But society was more polarized in 2022 compared to 2021. More and more people lost trust in the government to deal with both internal and external pressures, from environmental degradation to U.S. economic sanctions. Even the most brutal regimes need a constituency of supporters to survive. The Islamic Republic still had a constituency, primarily among the poorest segments of the population. But many families were living paycheck-to-paycheck or were dependent on government subsidies to meet their basic needs.

The regime could have an increasingly difficult time maintaining the loyalty of the working class if the economic situation does not improve in the near future. Iranian society is highly educated, connected to the outside world, and wants social mobility. But in the absence of meaningful reforms, people have increasingly felt trapped.