Iran and the world’s six major powers have less than a month to reach a deal that will ensure Tehran’s controversial nuclear program will be exclusively peaceful. Both sides are now intensifying their efforts to meet the November 24 deadline for an agreement. Leaders on both sides have noted that there has been progress on key issues and remain hopeful that a deal can be reached before the deadline.

Both Iranian and U.S. officials, however, have claimed that each other’s governments will be at fault if a deal is not reached. “If [a deal] does not happen, the responsibility will be seen by all to rest with Iran,” Undersecretary of State Wendy Sherman warned on October 23. “It is not clear if negotiations will reach a conclusion within the specified time frame” unless the other side gives up its “illogical excessive demands,” Deputy Foreign Minister Seyed Abbas Araghchi said on October 27 (click here for the latest remarks by U.S. and Iranian officials).

The following is a schedule for the next three weeks of diplomacy and a rundown of the three possible outcomes of the November talks — a deal, no deal or an extension.

•

November 7: E.U. foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton is

scheduled to meet with political directors from the P5+1 countries — Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States.

• November 9 and 10: Secretary of State John Kerry and Ashton are slated to meet with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif in Muscat, Oman.

•

November 11: Political

directors from the P5+1 and Iran are scheduled to meet in Muscat, Oman.

•

November 18: The final round of talks between Iran and the P5+1 is set to commence in Vienna. Kerry has

suggested that he and Zarif will both be in Vienna for the last few days of negotiations.

A Deal:

The temporary Joint Plan of Action states that

goal of the negotiations “is to reach a mutually-agreed long-term comprehensive solution that would ensure Iran’s nuclear program will be exclusively peaceful.” The following are excerpts from an article by

Joe Cirincione on six issues pivotal to an accord.

1. Limiting Uranium Enrichment

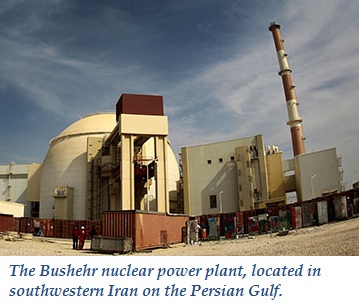

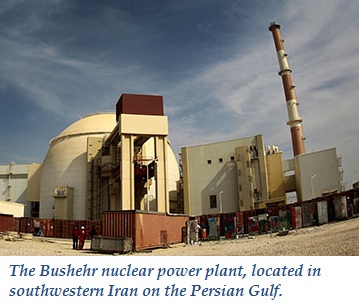

Iran’s ability to enrich uranium is at the heart of the international controversy. The process can fuel both peaceful nuclear energy and the world’s deadliest weapon. Since 2002, Iran’s has gradually built an independent capability to enrich uranium, which it claims is only for medical research and to fuel an energy program. But the outside world has long been suspicious of Tehran’s intentions because its program exceeds its current needs.

A deal may generally have to include:

•reducing the number of Iran’s centrifuges,

•limiting uranium enrichment to no more than five percent.

•capping centrifuge capabilities at current levels.

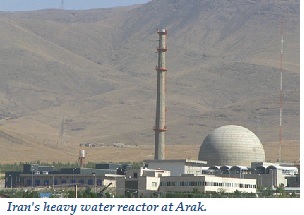

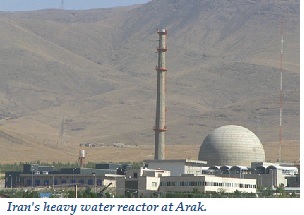

2. Preventing a Plutonium Path

Iran’s heavy water reactor in Arak, which is unfinished, is another big issue. Construction of this small research reactor began in the 1990s; the stated goal was producing medical isotopes and up to 40 megawatts of thermal power for civilian use. But the “reactor design appears much better suited for producing bomb-grade plutonium than for civilian uses,”

warned former Secretary of Defense William Perry and former Los Alamos Laboratory Director Siegfried Hecker.

In early February, Iranian officials announced they would be willing to modify the design plans of the reactor to allay Western concerns, although they provided no details.

3. Verification

The temporary Joint Plan allows more extensive and intrusive inspections of Iran’s nuclear facilities. U.N. inspectors now have daily access to Iran’s primary enrichment facilities at the Natanz and Fordow plants, the Arak heavy water reactor, and the centrifuge assembly facilities. Inspectors are now also allowed into Iran’s uranium mines.

A final deal will have to further expand inspections to new sites. The most sensitive issue may be access to sites suspected of holding evidence of Iran’s past efforts to build an atomic bomb. The IAEA suspects, for example, that Iran tested explosive components needed for a nuclear bomb at Parchin military base.

4. Clarifying the Past

The issue is not just Iran’s current program and future potential. Several

troubling questions from the past must also be

answered. The temporary deal created a Joint Commission to work with the IAEA on past issues, including suspected research on nuclear weapon technologies. Iran denies that it ever worked on nuclear weapons, but the circumstantial evidence about past Iranian experiments is quite strong.

Among the issues:

•research on polonium-210, which can be used as a neutron trigger for a nuclear bomb,

•research on a missile re-entry vehicle, which could be used to deliver a nuclear weapon, and

•suspected high-explosives testing, which could be used to compress a bomb core to critical mass.

“Iran needs to clarify issues related to possible military dimension and implement the additional protocol [to prove its nuclear program is entirely peaceful],” the head of the U.N. nuclear watchdog, Yukiya Amano,

said on October 31 at the Brookings Institution.

5. Sanctions Relief

Iran’s primary goal is to get access to some $100 billion in funds frozen in foreign banks and to end the many sanctions that have crippled the Iranian economy. Since the toughest U.S. sanctions were imposed in mid-2012, Iran’s currency and oil exports have both plummeted by some 60 percent.

The temporary Joint Plan of Action says a final agreement will “comprehensively lift UN Security Council, multilateral and national nuclear-related sanctions…on a schedule to be agreed upon.” (It does not, however, address sanctions imposed on other issues, such as support for extremist groups or human rights abuses.) The United States and the Europeans may want to keep some sanctions in place until they are assured that Iran is meeting new obligations.

6. The Long and Winding Road

The final but critical issue is timing: How long is a long-term deal? It will clearly require years to prove Iran is fully compliant. But estimates vary widely from five to 20 years. Another alternative is a series of shorter agreements that build incrementally on one another.

Click here for Joe Cirincione's full article on these six issues.

No Deal:

Undersecretary of State Wendy Sherman has warned that “

escalation will be the name of the game, on all sides,” if the talks collapse. Tehran’s resumption of work on the most sensitive aspects of its nuclear program could raise prospects for military action. President Barack Obama has

warned that he would seek to impose new sanctions on Iran in an agreement cannot be brokered. But enforcing sanctions could become much more

difficult if European and Asian countries, especially Russia and China, blame the failure of talks on U.S. unwillingness to compromise on Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity.

Extension:

The previous

extension pushed the due date for a deal back by four months to November 24. Neither side wants the talks to last any longer than necessary. But they may again opt for more time to negotiate if the alternative is a total collapse of the talks. Even if a general consensus is, however, reached on the major issues, experts may need additional time to hammer out the technical details. An extension could again allow for additional repatriation of frozen funds outside of Iran, perhaps in return for Iran taking more steps to roll back its nuclear program.

Iran’s ability to enrich uranium is at the heart of the international controversy. The process can fuel both peaceful nuclear energy and the world’s deadliest weapon. Since 2002, Iran’s has gradually built an independent capability to enrich uranium, which it claims is only for medical research and to fuel an energy program. But the outside world has long been suspicious of Tehran’s intentions because its program exceeds its current needs.

Iran’s ability to enrich uranium is at the heart of the international controversy. The process can fuel both peaceful nuclear energy and the world’s deadliest weapon. Since 2002, Iran’s has gradually built an independent capability to enrich uranium, which it claims is only for medical research and to fuel an energy program. But the outside world has long been suspicious of Tehran’s intentions because its program exceeds its current needs.  Iran’s heavy water reactor in Arak, which is unfinished, is another big issue. Construction of this small research reactor began in the 1990s; the stated goal was producing medical isotopes and up to 40 megawatts of thermal power for civilian use. But the “reactor design appears much better suited for producing bomb-grade plutonium than for civilian uses,” warned former Secretary of Defense William Perry and former Los Alamos Laboratory Director Siegfried Hecker.

Iran’s heavy water reactor in Arak, which is unfinished, is another big issue. Construction of this small research reactor began in the 1990s; the stated goal was producing medical isotopes and up to 40 megawatts of thermal power for civilian use. But the “reactor design appears much better suited for producing bomb-grade plutonium than for civilian uses,” warned former Secretary of Defense William Perry and former Los Alamos Laboratory Director Siegfried Hecker. The temporary Joint Plan allows more extensive and intrusive inspections of Iran’s nuclear facilities. U.N. inspectors now have daily access to Iran’s primary enrichment facilities at the Natanz and Fordow plants, the Arak heavy water reactor, and the centrifuge assembly facilities. Inspectors are now also allowed into Iran’s uranium mines.

The temporary Joint Plan allows more extensive and intrusive inspections of Iran’s nuclear facilities. U.N. inspectors now have daily access to Iran’s primary enrichment facilities at the Natanz and Fordow plants, the Arak heavy water reactor, and the centrifuge assembly facilities. Inspectors are now also allowed into Iran’s uranium mines. Among the issues:

Among the issues: