Garrett Nada

As an oil- hungry island nation, Japan’s position on Iran is fraught with inherent tensions. It has to balance an existential thirst for oil — to fuel industries, cars and homes — against a moral abhorrence of nuclear weapons, especially as the only country devastated by the world’s deadliest bombs in World War II. Iran is the nexus of those top priorities — and policy challenges.

As an oil- hungry island nation, Japan’s position on Iran is fraught with inherent tensions. It has to balance an existential thirst for oil — to fuel industries, cars and homes — against a moral abhorrence of nuclear weapons, especially as the only country devastated by the world’s deadliest bombs in World War II. Iran is the nexus of those top priorities — and policy challenges.

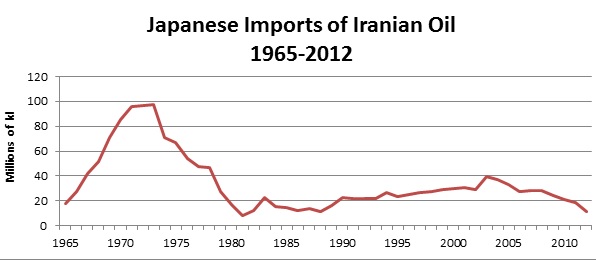

Japan is heavily industrialized and increasingly dependent on imported oil. It buys some 90 percent of its fuel from the Middle East. Iran was one of Japan’s top two sources of oil before its 1979 revolution. Afterwards, for more than three decades well into the 20th century, Iran continued to rank third or fourth. The Fukushima nuclear disaster deepened Japan’s need for oil and natural gas. Before the 2011 crisis, 54 nuclear reactors provided about 30 percent of Japan’s electricity needs. As of early 2013, safety concerns and public pressure had kept shut all but two plants.

At the same time, Japan is also deeply opposed to nuclear proliferation. It has joined in key international efforts to prevent Iran from getting a bomb. Since 2006, Tokyo has fully supported the four U.N. sanctions resolutions designed to prevent Iran from developing the world’s deadliest weapon. Since 2012, it has also complied with new U.S. sanctions that penalize other countries that buy Iran’s oil and gas.

Japan has also imposed its own sanctions on Iran’s banks and banned investment in new Iranian energy projects. “We took those steps as they are necessary to push for nuclear non-proliferation and prevent its nuclear development,” then Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshito Sengoku said in 2010, after announcing new sanctions. “We have traditionally close relations with Iran and from that standpoint, we will patiently encourage the country towards a peaceful and diplomatic solution.”

Japan intends to play a proactive role in solving the nuclear dispute because it “best understands the tragedy of the use of nuclear weapons and shoulders the responsibility to realize a world free of nuclear weapons,” according to its national security strategy.

Beyond trade and security, Japan’s relationship with Iran has become a double-edged sword diplomatically, both as an asset and a liability. Historically, Tokyo has had strong relations with Iran, beginning in the late 1920s. Each country has hosted the other’s leaders during both the monarchy and the theocracy. Since the 1979 revolution, Japan has occasionally been a conduit for sensitive messages between Iran and Western nations.

Beyond trade and security, Japan’s relationship with Iran has become a double-edged sword diplomatically, both as an asset and a liability. Historically, Tokyo has had strong relations with Iran, beginning in the late 1920s. Each country has hosted the other’s leaders during both the monarchy and the theocracy. Since the 1979 revolution, Japan has occasionally been a conduit for sensitive messages between Iran and Western nations.Japan and Iran share two cultural traits that inherently provide common bonds. Both countries emerged from ancient civilizations that each believes give them special standing in the world. “Iran is a country with a rich history” that Japan highly respects, Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida told his Iranian counterpart Mohammad Javad Zarif in a November 2013 visit to Tehran. The two countries also both share the eastern emphasis on respect and “face” as pivotal elements in diplomacy, politics and even trade.

Horrific shared experiences with weapons of mass destruction also bind the two countries. “Iran and Japan are two countries that have suffered greatly from weapons of mass destruction,” President Hassan Rouhani said in a mid-2013 meeting with Masahiko Komura, the special envoy of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Two of Japan’s major cities, Nagasaki and Hiroshima, were the first and only targets of atomic weapons. Even survivors who were exposed to very low doses of radiation showed a high risk for cancers decades after the 1945 bombing. Similarly, Iran suffered more than 50,000 casualties from Iraq’s repeated use of chemical weapons during the 1980-1988 war, according to a 1991 CIA report. Respiratory diseases and other health issues are still killing Iranian veterans and civilians alike due to low-dose exposure.

But relations also carry a price today. Tokyo cannot afford to cozy up to Tehran because of its close relationship with Washington, which is far more important politically, economically and for security. Japan still relies on the American military for its defense, and the United States is Japan’s second-largest trading partner, after China.

Economic Ties

In the past, Japan had occasionally defied its Western allies to maintain good relations with Iran. Japan was one of the few countries that purchased oil from Iran in 1953, after Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh nationalized the oil industry – then owned by the British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The United States and Britain were so opposed to Mossadegh that their intelligence services later jointly orchestrated a coup to restore the monarchy.

After Iran’s 1979 revolution, Tehran exported its first oil shipments to Japan on March 5 – the twelfth anniversary of Mossadegh’s death. By 2003, the height of Japanese-Iranian trade since the revolution, Tokyo imported 683,000 barrels of oil per day from Iran -- or 16 percent of its crude oil imports.

Japan’s total oil imports from Iran then began decreasing due to its own economic problems – long before the United States tightened sanctions in mid-2012. Japan suffered from more than a decade of high inflation between 2003 and 2013. The economy fell into recession three times since 2008. So oil consumption decreased.

Sanctions have also taken a bite out of Japan’s oil purchases. Japanese imports from Iran fell 39 percent – from 314,129 barrels per day to 191,032 barrels per day – in 2012. Japanese oil companies continue to buy Iranian oil, but only with a special exemption from U.S. sanctions. Washington grants waivers to Japan and other countries every six months for curbing their crude oil purchases. Over the first 11 months of 2013, oil trade dropped another five percent to 178,139 barrels per day. In 2013, Japan imported less Iranian oil than at any time since 1981, when Iran was embroiled in a war with Iraq.

But Tokyo and Tehran have not allowed the nuclear dispute to degrade their longstanding relationship. Iran still considers Japan an important trade partner and potential future investor in Iran’s energy sector. Inpex, a private Japanese oil company, used to own a 75 percent stake in developing the South Azadegan oil field. But it reduced its stake to 10 percent in 1996 and pulled out completely in 2010 to avoid U.S. sanctions.

Among key figures for 2012, according to the Japan External Trade Organization and Ministry of Finance:

● Japan-Iran trade totaled about $8.66 billion

● Japan imported $8 billion worth of goods from Iran, 99 percent of which was crude oil.

● Japan exported $658 million of goods to Iran, largely machinery, metals, chemicals and non-metallic minerals.

Japanese companies are risk averse because they could face sanctions ― and jeopardize their reputations ― just for doing for doing business with Iran. Toyota Motor Corporation voluntarily halted car exports to the Islamic Republic in 2010, citing the “the international environment.”

But private Japanese companies are also yearning to do business with Iran again, given its market of 79 million consumers. Japanese products were popular in Iran, especially during the 1980s and early 1990s. But the import of cheaper goods from Korea, and later China, ramped up the competition. Japanese auto and electronics manufacturers particularly want to reenter the market. And for them, Iran appears comparatively more stable than the tumultuous Arab world since the 2011 uprisings began. The mid-2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani, followed by his outreach to improve Iran’s relations with the world further, has further encouraged Japanese diplomats and businesses.

Security Concerns

Japanese opposition to Iran’s nuclear trajectory is somewhat complicated by its own unique nuclear program. Japan is the only non-weapons state under the Non-Proliferation Treaty that has major fuel cycle facilities that could enable to make a bomb ― the so-called “nuclear threshold.” For years, Iranian officials have claimed they are pursuing the “Japan model” of nuclear development.

Japanese opposition to Iran’s nuclear trajectory is somewhat complicated by its own unique nuclear program. Japan is the only non-weapons state under the Non-Proliferation Treaty that has major fuel cycle facilities that could enable to make a bomb ― the so-called “nuclear threshold.” For years, Iranian officials have claimed they are pursuing the “Japan model” of nuclear development. To defuse the issue, Japan is eager to see the temporary agreement between Iran and six world powers — the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia — produce a long-term deal. Tokyo repeatedly raises the issue in its interactions with Tehran. Its Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a three-point statement on Rouhani’s election in mid-2013 that encouraged the new president to engage in serious dialogue to end the nuclear dispute.

Tokyo prefers a peaceful settlement for its own energy security too. When tensions rise, Tehran has occasionally warned that it could block the Strait of Hormuz, an oil transit chokepoint through which some 20 percent of oil traded worldwide flows. The strait’s closure, or U.S. or Israeli military strikes on Iran, could endanger Japan’s energy supply. Japan’s first national security strategy, released in December 2013, prioritizes stability in the Middle East as “inseparably linked to the stable supply of energy, and therefore Japan’s very survival and prosperity.” So Tehran’s production of a nuclear bomb would be a disheartening defeat for Tokyo.

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP. He traveled to Japan in January 2014.

Photo credits: President.ir, Map by Aridd at en.wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org