Robin Wright and Garrett Nada

The new diplomacy between Iran and the world’s six major powers faces growing opposition from key players in the Middle East, including the oil-rich and influential Gulf states. The Sunni sheikhdoms are nervous the Shiite theocracy will do a deal on its nuclear program that leaves Tehran with a residual capability to eventually build a bomb, either by retaining basic knowledge of a weapons program or controlling the pivotal fuel production for a weapon.

More broadly, however, Saudi Arabia and the smaller monarchies fear that a diplomatic deal will allow rival Iran to shed its pariah status and reemerge as the Gulf powerhouse—to their disadvantage. Iran’s split with the West after the 1979 revolution had increased the influence of Saudi Arabia particularly as an alternative pillar of U.S. policy. A deal on Iran’s nuclear program could in turn lead to rapprochement with Washington that would diminish Gulf leverage.

Tensions between Iran and its Gulf neighbors have not eased despite new President Hassan Rouhani’s call for improving relations between Tehran and Riyadh. “We are not only neighbors, we are brothers,” he said shortly after his election in June. “We have had very close relations, culturally, historically and regionally.” He emphasized this point in a tweet following his October 15 call with Qatar's emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani.

But suspicions remain deep. After the Iranian and Saudi foreign ministers met this fall, Prince Saud al Faisal was openly skeptical. “What we want now is to see that desire materialize on the ground,” he said. “They preach what they do not practice, and practice what they do not say.”

Opposition to a deal plays out on four levels:

• Iran’s military capabilities.

• The sectarian balance of power between Shiite Iran and the Sunni sheikhdoms.

• The ethnic balance between Persians and Arabs.

• Ties with the United States.

The Military Balance

The Gulf sheikhdoms are concerned that even a nuclear capability – no bomb, but the ability to assemble a weapon in a short time – would change the strategic balance of power in Iran’s favor.

Iran currently has more conventional and unconventional troops than the six sheikhdoms in the Gulf Cooperation Council combined. Tehran has more than twice as many ground, air and naval forces as Saudi Arabia, its main rival and the largest of the GCC countries. But the GCC has a potential advantage in quality of armor, artillery and mobility. The six sheikhdoms collectively have more combat planes--666 fixed wing combat aircraft that are also more advanced than Iran’s 334 largely outdated planes. The Gulf navies collectively have some 598 crafts, while Iran has about 280. Iran’s forces would probably not be able to sustain a long campaign against GCC forces, especially if they were backed by the United States.*

Iran currently has more conventional and unconventional troops than the six sheikhdoms in the Gulf Cooperation Council combined. Tehran has more than twice as many ground, air and naval forces as Saudi Arabia, its main rival and the largest of the GCC countries. But the GCC has a potential advantage in quality of armor, artillery and mobility. The six sheikhdoms collectively have more combat planes--666 fixed wing combat aircraft that are also more advanced than Iran’s 334 largely outdated planes. The Gulf navies collectively have some 598 crafts, while Iran has about 280. Iran’s forces would probably not be able to sustain a long campaign against GCC forces, especially if they were backed by the United States.* A nuclear capability would be a game-changer, however. The sheikhdoms are particularly concerned that Iran might use the mere knowledge of how to produce the world’s deadliest weapon to increase its regional leverage, intimidate rivals, promote its revolutionary ideology, and control the Gulf waters through which some 40 percent of the world’s oil flows.

As a result, Saudi Arabia and its neighboring sheikhdoms Gulf would prefer virtually the same limits on Iran’s program demanded by Israel, including closure of key facilities and an end to enrichment of uranium.

The Sectarian Balance

The rivalry between the Gulf and Iran actually predates the 1979 revolution. It reflects the deepest schism within the Islamic world dating back to the seventh-century split between Sunnis and Shiites.

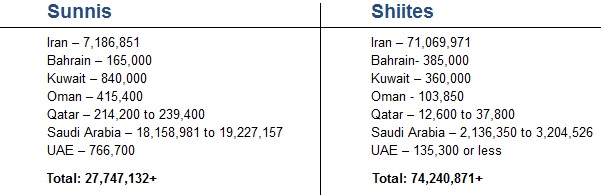

Iran has the world’s largest Shiite population; it is the only country led by Shiite clergy. Both factors made it the de facto leader of the Shiite world politically, even though the key center of Shiite scholarship is in Iraq.

Saudi Arabia is the birthplace of Islam and the guardian of its two holiest sites. The Gulf sheikhdoms are all ruled by Sunni monarchies, but all have Shiite populations. Shiites are the majority in Bahrain, where many have been involved in protests against the government since 2011. Saudi Arabia has more than 2 million Shiites, many of whom live and work in the oil-fields of the restive Eastern Province.

Both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia have long claimed that Iran was trying to foment unrest among their Shiite minorities. “Clerical authorities in Iran still tend to act as if they lead the Islamic World--issuing ultimatums, intimidating their neighbors, and inciting dissidence and revolution,” Prince Turki al Faisal, the former Saudi intelligence chief, said in October.

Numerically, Iran’s 79 million population is almost twice as large as the 45 million people who populate the six Gulf sheikhdoms, especially since the Gulf numbers include foreign residents. The Sunni monarchies are concerned that Iran’s acquisition of a nuclear capability might lead the Shiite theocracy to more actively support their brethren inside the Gulf sheikhdoms.

The Ethnic Balance

Gulf fears about Iran also have roots in centuries-old competition between Arabs and Persians for regional dominance. Tensions played out most recently during the eight-year war between the Arab regime in Iraq and the Persians of Iran in the 1980s. It was sparked by rival claims on the strategic Shatt-al Arab waterway along their border, but it was more broadly about regional influence. The Iran-Iraq war still ranks as the bloodiest conflict in the modern Middle East, producing more than 1 million casualties.

Again numerically, Iran’s Persians significantly outnumber the Gulf Arabs. Half of the sheikhdoms also have Persian minorities. The Gulf sheikhdoms fear that an Iran with even a nuclear capability would give the Persians greater leverage over key regional issues, from oil prices to control of transportation routes. Gulf Arabs even oppose calling the strategic waterway that divides Iran and the sheikhdoms the “Persian” Gulf because it implies Iranian control or influence.

“The Iranian leadership’s meddling in Arab countries is backfiring,” Prince Turki said. “Arabs will not be forced to wear a political suit tailored in Washington, London, or Paris. They also reject even the fanciest garb cut by the most skillful tailor in Tehran.”

U.S. Ties

Saudi Arabia has been one of two pillars of U.S. policy in the Arab world —along with Egypt—since the late 1970s. After Iran’s 1979 revolution, the United States had both strategic and economic interests in giving GCC forces a qualitative edge over Iran. It invested heavily in the modernization of Gulf militaries through arms transfers worth tens of billions of dollars. In turn, the Gulf’s defense strategy against revolutionary Iran has been based on close security ties with the United States.

Iran’s new diplomacy—including the first meeting between the Iranian and American foreign ministers in September—has left the Gulf states feeling more vulnerable. The unprecedented phone call between President Obama and President Hassan Rouhani was especially unnerving for the ruling sheikhs, who view a potential U.S.-Iran rapprochement as harmful to both their relations with Washington and their own long-term interests. Abdullah al Askar, chairman of the foreign affairs committee in Saudi Arabia's Shoura Council, reflected local sentiment. “If America and Iran reach an understanding,” he told Reuters, “it may be at the cost of the Arab world and the Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia."

Robin Wright has traveled to Iran dozens of times since 1973. She has covered several elections, including the 2009 presidential vote. She is the author of several books on Iran, including "The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and transformation in Iran" and "The Iran Primer: Power, Politics and US Policy." She is a joint scholar at USIP and the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Garrett Nada is a senior program assistant at USIP.

* Based on “The Gulf Military Balance” report by Anthony Cordesman and Bryan Gold. Click here for Cordesman’s chapter on Iran’s conventional military.

* *Based on estimates derived from the U.S. State Department and CIA World Factbook figures

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org