Among Iran’s 31 provinces, Kurdistan in the northwest is one of the most restive. It is one of three border regions—along with Khuzestan in the southwest and Sistan and Baluchistan in the east—with volatile ethnic issues that have led to protests, strife and calls for autonomy or independence. Stability in Kurdistan is vital to security on the border with Iraq and maintaining territorial integrity. The province is a microcosm of challenges from Iran’s many ethnic minorities.

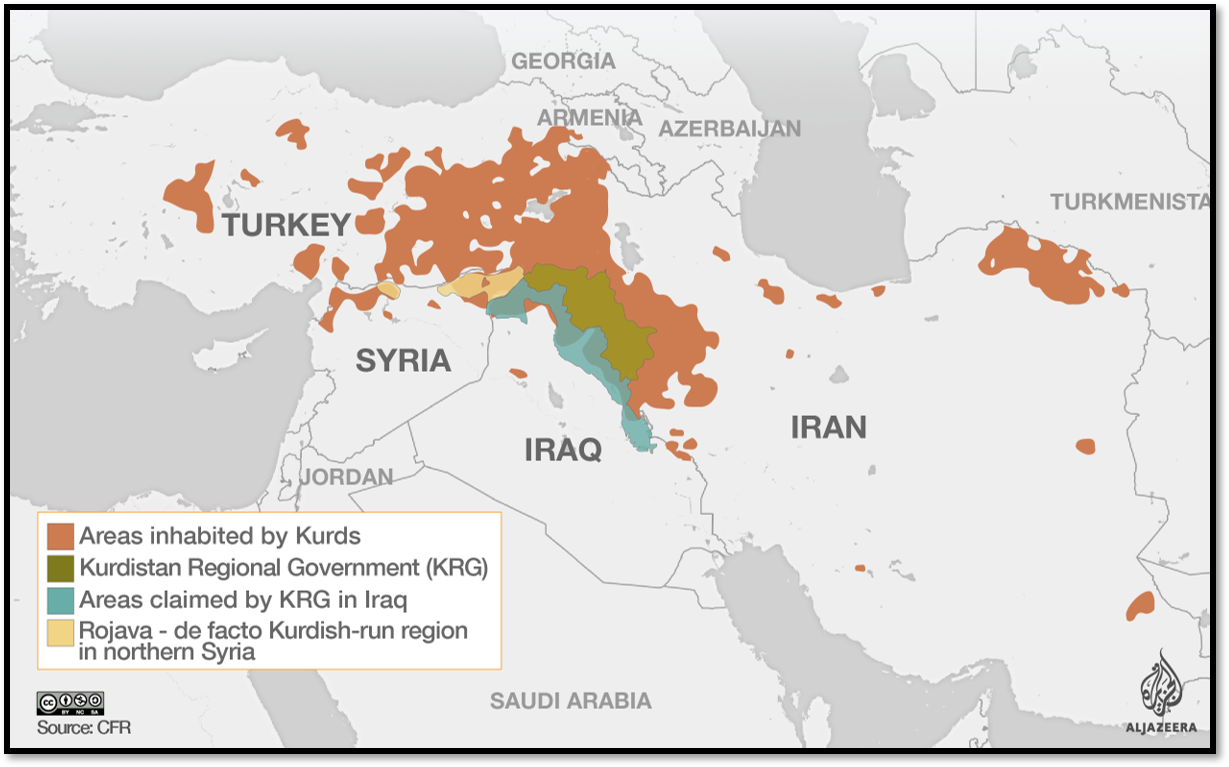

Iran and its neighbors have long perceived the Kurds as a threat due to their numbers, geographic distribution and resistance to central authority. The Kurds are the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East. The Kurds are the majority in Kurdistan province but a minority in Iran.

Iran and its neighbors have long perceived the Kurds as a threat due to their numbers, geographic distribution and resistance to central authority. The Kurds are the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East. The Kurds are the majority in Kurdistan province but a minority in Iran.

As of 2020, Iran had between eight and 10 million Kurds, or roughly 10 percent of Iran’s 84 million people. Kurds, who can trace their roots back more than four millennia, are the third largest ethnic group after Persians and Azeris. They are primarily concentrated in Kurdistan, West Azerbaijan, Kermanshah and Ilam provinces. Many protests and clashes with regime security forces have played out in Kurdistan, which is estimated to have the highest percentage of Kurds in Iran. Kurdish separatist groups have sought independence since 1918, both during the monarchy and since the 1979 revolution.

Related Material:

Kurdistan is one of three border provinces — each with disaffected ethnic minorities — that the central government has neglected for decades, according to Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran. (Khuzestan province is home to the largest Arab community. Sistan and Baluchistan province is home to the largest number of Baluch).

“Iran, both before and after the 1979 Revolution, made a big mistake by treating all kinds of problems and grievances in these provinces with a heavy-handed national security approach—as potential gateways for separatism or invasion,” Ghaemi said. “In my 20 years of tracking executions in Iran, Arab and Kurdish prisoners have been executed much more frequently than others.”

Kurdistan is slightly larger than Maryland. It shares a 124-mile border with Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region. The western half of the province is largely mountainous; the eastern half includes fertile plains that produce fruits, vegetables and grains. Kurdistan has historically been one of Iran’s top wheat producers. As of the 2016 census, Kurdistan’s population was 1.6 million, or about two percent of Iran’s total population. More than 70 percent of its residents live in cities—close to the national average. More than 400,000 people live in and around Sanandaj, the provincial capital.

Regional Flashpoint

At least 25 million Kurds are spread across Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. They are the largest minority in the world without a state. The Kurds were promised their own country in the Treaty of Sevres after World War I, but Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk rejected the agreement. In Kurdish, the northwestern part of Iran is called “Rojhelat,” which means “East” Kurdistan.

The Kurds have never had a modern state. But Iran’s Kurds arguably came the closest in January 1946, when separatists declared independence from Iran and founded the short-lived Republic of Mahabad in the northwest. The Kurdish mini-state enjoyed the financial and political backing of the Soviet Union, but it fell to the shah’s military in December 1946 after Soviet forces withdrew from Iran. The legacy of the short-lived Republic of Mahabad further spurred Kurdish nationalism. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) of Iraq adopted and still flies the same flag.

The Kurds have never had a modern state. But Iran’s Kurds arguably came the closest in January 1946, when separatists declared independence from Iran and founded the short-lived Republic of Mahabad in the northwest. The Kurdish mini-state enjoyed the financial and political backing of the Soviet Union, but it fell to the shah’s military in December 1946 after Soviet forces withdrew from Iran. The legacy of the short-lived Republic of Mahabad further spurred Kurdish nationalism. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) of Iraq adopted and still flies the same flag.

In the 21st century, Kurdish issues have ignited across the four countries with large Kurdish communities. In 2017, Iraq’s Kurdish provinces held a referendum on independence. Nearly 93 percent of 4.5 million voters supported turning the KRG and some disputed oil-rich cities, such as Kirkuk, into an independent state.

Iranian leaders roundly criticized the referendum and warned of further instability in a war-torn region. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei accused the United States and foreign powers of trying to “create a new Israel” to serve their interests. President Hassan Rouhani called the plan to split Iraq a “foreign sectarian plot.”

Tens of thousands of Kurds in #Iran'ian occupied #Kurdistan celebrate the independence referendum in Bashur. #Twitterkurds #Rojhelat pic.twitter.com/ZFgCqCLXih

— PDKI (@PDKIenglish) September 25, 2017

Meanwhile, thousands of Iranian Kurds took to the streets of Baneh, Saghez and Sanandaj in Kurdistan province to support the KRG move. The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan, a political group and militia exiled in northern Iraq, also supported the referendum. In the Kurdish regions of Iran, the Revolutionary Guards and the Basij paramilitary have set up an extensive command-and-control system—second only to Tehran province—to deal with unrest and cross-border attacks by Kurdish militants.

Ethnic, Sectarian and Political Tensions

Kurds have long fought for their right to self-govern. “For more than 4,000 years the intransigent Kurds have resisted all efforts by outsiders to subjugate them,” according to a CIA report from 1980 on the Kurds of Iran. “Their fierce independence, however, has also torpedoed occasional attempts by inspired or ambitious leaders to unite them into a single state.” Kurdish society has traditionally been based on tribe and clan. Rivalries along tribal or clan lines have often stymied attempts at unification.

Iranian governments—under both the monarchy and the theocracy—have suppressed Kurdish identity by limiting to use of the Kurdish language in schools and government services. The 1906 constitution declared that Persian was the official language of Iran; it required members of parliament be able to speak, read and write Persian.

Iranian governments—under both the monarchy and the theocracy—have suppressed Kurdish identity by limiting to use of the Kurdish language in schools and government services. The 1906 constitution declared that Persian was the official language of Iran; it required members of parliament be able to speak, read and write Persian.

Reza Shah Pahlavi, who ruled from 1925 to 1941, tried to centralize control over Iran by assimilating minorities. The government banned the use of minority languages in education, administration and the media. Several dialects of Kurdish are spoken in Iran, but most Iranian Kurds speak Sorani – as opposed to Kurmanji (spoken widely in Iraq, Turkey and Syria) or Palewani (spoken by some Iranian Kurds) .

Mohammad Reza Shah, who ruled from 1941 to 1979, allowed the broadcast of Kurdish radio programs. But the shah reduced the power of Kurdish tribal leaders, known as khans. In the 1960s and 1970s, his government also broke up the khans’ large estates and redistributed their land to peasants, which weakened tribal bonds and Kurdish identity.

Since the 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic has continued to use Persian as the official language. But it has allowed the use of Kurdish in publications and the media, albeit under state supervision. Under President Hassan Rouhani, who took office in 2013, the government has allowed more Kurdish cultural activities. But as of 2019, the central government “continued to use the law to arrest and prosecute Kurds for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and association,” according to the State Department’s annual human rights report. “The government reportedly banned Kurdish-language newspapers, journals, and books and punished publishers, journalists, and writers for opposing and criticizing government policies.”

In July 2020, the judiciary sentenced Zahra Mohammadi, a 29-year-old Kurdish civil rights activist, to 10 years in prison for undermining national security. Mohammadi directed the Nojin Cultural Association, a group that teaches Kurdish language and literature. She was initially accused of having links to two armed opposition groups, but those charges were dropped.

The Kurds have faced suppression and neglect from the central government. The Islamic Republic has “disproportionately targeted minority groups, including Kurds, Ahwazis, Azeris, and Baluchis, for arbitrary arrest, prolonged detention, disappearances, and physical abuse,” according to the State Department 2019 Human Rights Report. “These ethnic minority groups reported political and socioeconomic discrimination, particularly in their access to economic aid, business licenses, university admissions, job opportunities, permission to publish books, and housing and land rights.”

In early 2021, Iranian authorities arrested dozens of Kurdish civil society activists, labor rights activists, environmentalists, writers and university students, including individuals with no known history of activism. Between January 6 and February 3, authorities detained at least 88 men and eight women in five provinces: Alborz, Kermanshah, Kurdistan, Tehran and West Azerbaijan provinces. Three dozen civil society and human rights organizations—including Human Rights Watch, the Center for Human Rights in Iran and the Kurdistan Human Rights Network—issued a joint call to the international community to respond.

High unemployment among Kurds has forced many to take jobs as “kulbars,” or smugglers and couriers carrying goods between Iraq and Iran. The job is dangerous due to harsh weather, mountainous terrain, land mines and Iranian border patrols. In 2019, 50 kulbars were reportedly killed and 144 injured by border guards.

Government investment helped improved Kurdistan’s literacy rate, just 28 percent in 1979. In the 2016 census, the province had a literacy rate of 84.5 percent but still lagged behind other provinces, including Tehran, which had a literacy rate of 93 percent. Many rural districts in Kurdistan only have primary schools.

The central government has also discriminated against Kurds for their faith. Iran is a predominantly Shiite country. Most of Iran’s Kurds are Sunni, many of whom opposed the adoption of Shiism as the official state religion after the 1979 revolution. “The religious institutions of Sunni Kurds are generally blocked, while those of Shi’as are encouraged and supported by the state,” Amnesty International reported in 2008. The state has also occasionally harassed Sunni clerics.

Sunnis are the majority in Kurdistan province but have poor access to government jobs, partly due to the “gozinesh” process which screens applicants for their allegiance to the Islamic Republic and the principle of velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist), a concept derived from Shiite Islam. The screening process has limited the employment prospects for non-Shiite Kurds and other minorities with the government – the largest employer in Iran. Abdollah Ramazanzade, Kurdistan’s first Kurdish governor, was a Shiite; he was appointed by President Mohammad Khatami in 1997.

Opposition Groups

Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI)

Overview: Established in 1945, the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) is among the oldest and most active Kurdish opposition groups. The movement, which is banned in Iran, engages in both political and military activities. Its founder was Qazi Muhammad, who led the short-lived Republic of Mahabad. The small state defied Tehran for nearly a year before the shah’s forces reestablished control in December 1946. Muhammad was hanged for treason in 1947. For the next three decades, the PDKI operated primarily underground.

The PDKI participated in the 1979 revolution, but the new government rejected demands for Kurdish autonomy or independence. The PDKI, along with several other Kurdish groups, waged an uprising from 1979 to 1981 in the Kurdistan and West Azerbaijan provinces. It was the largest rebellion against the fledgling Islamic government, but the uprising was crushed by the Revolutionary Guards. Some 10,000 people were killed, including Kurdish fighters, government troops and civilians. The PDKI – with support from Iraq – continued to attack Iranian forces for another two years. But by 1984, many of PDKI leaders and members had fled into exile in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The PDKI participated in the 1979 revolution, but the new government rejected demands for Kurdish autonomy or independence. The PDKI, along with several other Kurdish groups, waged an uprising from 1979 to 1981 in the Kurdistan and West Azerbaijan provinces. It was the largest rebellion against the fledgling Islamic government, but the uprising was crushed by the Revolutionary Guards. Some 10,000 people were killed, including Kurdish fighters, government troops and civilians. The PDKI – with support from Iraq – continued to attack Iranian forces for another two years. But by 1984, many of PDKI leaders and members had fled into exile in Iraqi Kurdistan.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the PDKI launched intermittent attacks across the border from Iraq. But the group faced several setbacks, including the assassinations of two leaders in 1989 and 1992. The PDKI blamed both on Tehran. Its ability to challenge the regime weakened in the 1990s; it declared a unilateral ceasefire in 1996.

In 2006, a minority wing broke off from the group over personal and ideological differences. The PDKI remained largely dormant until 2016, when it launched its “Rasan” (or Uprising) – campaign to recruit new members and launch cross border attacks against the Revolutionary Guards. Over the next four years, it launched sporadic clashes with Iranian security forces.

Leadership: The current leader is Mustafa Hijri, a career educator who was elected to the fourth congress in 1979. Hijri served in several top positions, including deputy leader and interim leader before he was elected secretary general in 2006. The PDKI’s highest governing body is a congress, which convenes every four years. Each congress elects a Central Committee comprised of 25 permanent and 10 substitute members, who make policy decisions between congressional sessions.

In an interview in 2015, Hijri condemned Tehran for cracking down on “any form of dissent in Kurdistan” while spending “billions of dollars on terrorist groups outside of Iran instead of investing inside the country.” Hijri urged the United States to do more to support Kurdish freedom.

Goals: The PDKI is both a Kurdish nationalist and a democratic socialist party. It is committed to “democracy, liberty, social justice and gender equality.” It is a member of the Socialist International. It has repeatedly demanded Kurdish independence. Since 2004, however, the group has modified its demands; it called for greater autonomy within a federal democratic system in Iran. The PDKI has used armed resistance against the central government while promoting its ideology online and in border towns.

Military: The PDKI is estimated to have between 1,000 and 2,000 fighters spread across Iran and Iraq. The PDKI’s “Peshmerga,” or “those who face death,” include male and female fighters. Since the 1990s, it has been primarily based in the Koy Sanjaq district of Iraq’s Erbil province, about 40 miles from the Iranian border. The PDKI has claimed to have sleeper cells in Iran as well.

Kurdistan’s Peshmerga Forces will always prepare and except the worst and only rely on the fact that our mountains are our only friends. #Kurdistan #Rojhelat #Rasan #Peshmerga #PDKI #KDPI #Twitterkurds pic.twitter.com/uoDOmAprai

— PDKI (@PDKIenglish) December 24, 2018

Foreign Relations: Since the 1980s, the PDKI has depended on its brethren in Iraq for refuge. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) of Iraq has allowed the PDKI to use its territory as its base of operations. In 2017, the PDKI supported the KRG’s referendum on independence.

Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK)

The Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK), founded in 2004, is movement that has both a militia and a political wing, the Free and Democratic Society of East Kurdistan (KODAR). Both are banned in Iran. PJAK was an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), originally based in Turkey that later moved its operations to Iraq. PJAK has claimed that it is a separate organization, but some of its members were in the PKK and the two groups have similar ideologies. Its leader is Abdul Rahman Haji Ahmadi, who called them “brother parties” that share “the same core.”

#Iran’s Revolutionary Guards kill five Kurdish PJAK militants https://t.co/1c4zjWJL5l pic.twitter.com/GSIafbNdu5

— Rudaw English (@RudawEnglish) June 14, 2016

PJAK’s militia launched intermittent attacks against government targets, mostly in Kurdistan and Kermanshah provinces, from 2004 to 2011. It declared a unilateral ceasefire after 180 PJAK fighters were killed during three months of intense fighting in 2011. The group has long used the Qandil Mountains, along the border with Iraq, as a base of operations.

Leadership: Ahmadi directs the group’s activities from Cologne, Germany. In 2010, Germany rejected an Iranian request for his extradition. In 2011, Ahmadi called for all ethnic groups in Iran to topple the regime. “The Iranian government will not fall just by the Kurdish people revolting,” he said. “But, if all the nations in Iran start a revolution together, then they will be able to bring the Iranian government down.”

Goals: The PJAK has called for a “democratic confederacy” to replace the theocracy. It is committed to greater autonomy for Iran’s diverse peoples as well as gender equality. It has worked to build grassroots support and simultaneously urged Kurdish members of parliament to press for Kurdish rights. In 2017, KODAR called for a boycott of the presidential election, but it did not discourage Kurds from running in local elections.

Siamand Moeini of PJAK: Iran is not prepared to accept Kurdish demands thus we can’t reach an agreement with them https://t.co/VFZTH0nJBr to form a united front against Tehran, @PDKIenglish & other Kurdish parties have asked PJAK to accept overthrow of regime is the only option pic.twitter.com/QoYUYtqJCm

— Fazel Hawramy (@FazelHawramy) August 20, 2018

Militia: The group retained armed fighting forces after the ceasefire in 2011 and has occasionally clashed with regime forces. It is estimated to have between 2,000 and 3,000 fighters, including women.

Foreign Relations: Ahmadi reportedly visited Washington in 2007, but did not meet with U.S. officials. The United States designated PJAK a terrorist organization in February 2009. PJAK does not have formal alliances with other countries. It does, however, receive support from the PKK in Iraq.

Komala

Overview: The Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan was formed by students and intellectuals in 1969. Its first and current leader is Secretary General Abdullah Mohtadi. It participated in the 1979 revolution and established a political party in March 1979. Komala’s platform is socialist. It calls for a democratic, secular and federal Iran. Komala fought alongside the PDKI and other groups during the Kurdish rebellion in 1979 and 1980. The group went into exile in Iraq in 1983. It suspended attacks against Iran in the early 1990s.

In 2017, Komala announced the resumption of its armed campaign against the regime. But it has avoided major attacks that would provoke a wider conflict with the Iranian military. “We will keep the right to retaliate in the appropriate time,” Mohtadi said in 2018.

In 2017, Komala announced the resumption of its armed campaign against the regime. But it has avoided major attacks that would provoke a wider conflict with the Iranian military. “We will keep the right to retaliate in the appropriate time,” Mohtadi said in 2018.

Leadership: Mohtadi is from a family long active in Kurdish politics. His father was a minister in the Republic of Mahabad in 1946. Mohtadi founded Komala with fellow students in Tehran in 1969. In the 1970s, he was arrested three times and spent more than three years in jail for his activism against the shah.

Goals: Komala calls for a “democratic secular pluralist federal Iran,” civil liberties, human rights, and tolerance but its ideology is socialist. It has focused on regime change in Iran rather than establishing a Kurdish state. It has sought to form a united front of other minorities while mobilizing Iran’s Kurdish population. The party’s ideology was initially communist. In 1983, it joined the Communist Party of Iran, but some members left to form the Workers Communist Party in 1991. The group splintered again 2000. One branch, the Komala Communist Party of Iran, which also calls itself Komala, is still communist. It is significantly smaller (and not profiled here).

Military: Komala is estimated to have less than 1,000 fighters. It has clashed with Iranian forces, but since the 1990s it has primarily used its Peshmerga fighters to defend training camps and Kurdish settlements in Iraq. Some of its fighters joined the fight against ISIS in Iraq in 2014.

Graduation day for our new batch of #Peshmerga's.

— Komala (@Komala_english) January 19, 2016

Congratulations dear #Kurdistan, your children will protect you. pic.twitter.com/Q0SEFRGYpX

Foreign relations: Mohtadi spoke with State Department officials in 2007 but did not secure U.S. support. Komala registered as a lobbying group with the Justice Department in 2018. It formed an alliance with the PDKI in 2012.

Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK)

Overview: Founded in 1991 by Said Yazdanpanah, the Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK) is an Iranian Kurdish separatist movement that is engaged in both political and military activities. It is based in northern Iraq. The PAK is committed to an independent Kurdish state that would bring together territory from Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

Leadership: Yazdanpanah, a guerilla fighter, was assassinated, allegedly by Iranian agents in 1991, four months after he established the Revolutionary Union of Kurdistan – the precursor to the PAK between 1991 and 2006. His brother, Hussein Yazdanpanah, replaced him as the group’s leader. At a congress in October 2006, the group changed its name to PAK and elected Ali Qazi – son of the president of the short-lived Republic of Mahabad – as its president. Yazdanpanah is the vice president.

Goals: The party seeks an independent Republic of Kurdistan in the Middle East. Its platform is committed to a secular democracy, pluralism, women’s rights and respecting religious diversity in a parliamentary system. It joined the PDKI’s uprising against the Iranian regime in 2016. “In Iran we will fulfill our duty. It is always Tehran that has been fighting us, killing, executing, but the world never reports on this,” Yazdanpanah said in 2016. “We now have very active, strong forces.”

Goals: The party seeks an independent Republic of Kurdistan in the Middle East. Its platform is committed to a secular democracy, pluralism, women’s rights and respecting religious diversity in a parliamentary system. It joined the PDKI’s uprising against the Iranian regime in 2016. “In Iran we will fulfill our duty. It is always Tehran that has been fighting us, killing, executing, but the world never reports on this,” Yazdanpanah said in 2016. “We now have very active, strong forces.”

Military: In 2014, the PAK joined Iraqi Kurds to fight ISIS. In 2016, Yazdanpanah claimed that the group had received three rounds of training from the U.S. military in 2015. “We took advantage of every opportunity to get training, by the Americans, French, Brits,” he said. CENTCOM later denied training PAK fighters.

In 2016, the PAK militia kicked off a new offensive with an attack on an Iranian military parade near Sanandaj; it claimed to kill two Iranian forces. “We are only 1,000 [fighters], but we fight like 10,000,” Yazdanpanah said in 2019. In May 2020, the PAK united its Peshmerga divisions into the “Kurdistan National Army” and called on other Kurdish parties to join forces.

Foreign relations: The PAK has close ties to the PDKI as well as the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in Iraq.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of “The Iran Primer” at the U.S. Institute of Peace. Caitlin Crahan is a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.