James Dobbins

- Under President George W. Bush, the United States and Iran twice engaged in extended and substantive diplomatic talks.

- In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, bilateral U.S.-Iranian contacts produced the most significant cooperation since the 1979 revolution, as Iranian officials helped the United States form a new Afghan government. Despite this, only weeks later, President Bush included Iran in the “axis of evil,” and threatened to use force to halt its nuclear program.

- Iran persisted for more than a year to offer assistance to the United States, first in Afghanistan and then Iraq. But Washington failed to accept any of Tehran’s offers.

- In 2007, talks were held between top U.S. and Iranian envoys in Iraq. These exchanges were highly confrontational, but Iranian behavior in Iraq did moderate somewhat thereafter.

- During his first year in office, President Barack Obama tried unsuccessfully to open a high-level dialogue with Iran, while at the same time seeking to bypass the populist and confrontational President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in favor of the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

- The 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani and the appointment of Mohammad Javad Zarif as foreign minister created a new opportunity for Iranian-American engagement, initially focused almost exclusively on nuclear issues.

- If the final nuclear agreement can be implemented, the two sides may gradually extend their dialogue to other issues, notably Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. But domestic opposition on both sides will likely restrict the pace of any further collaboration. The United States will also be constrained by the concerns of its Arab allies.

Overview

The 9/11 attacks opened a brief period of cooperation between the United States and Iran. Tehran had long opposed both the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Iran publicly condemned these attacks on the United States and privately offered to assist American efforts to overthrow the Taliban regime. Iran had considerable influence with the Northern Alliance, the insurgency that had been battling the Taliban since the mid-1990s. Tehran used this influence to help the United States secure agreement among all elements of the Afghan opposition on a new government that took office in Kabul in December of 2001, only a few weeks after the Taliban’s ouster.

A month later, President Bush called Iran, along with North Korea and Iraq, the new “axis of evil,” and threatened to use military force to halt their nuclear programs. The Iranian government nevertheless continued to offer cooperation on Afghanistan, volunteering to help the United States raise and train a new Afghan army. The Bush Administration ignored this offer, as it did an even more far-reaching proposal of cooperation a year later, after the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

In 2005, the hardline mayor of Tehran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, replaced reformist President Mohammad Khatami. Over the next five years, Tehran showed little interest in cooperating with the United States. Ahmadinejad wrote to both Bush and Obama, but neither responded. Bush authorized a series of talks in Baghdad in 2007 between the U.S. and Iranian ambassadors, which involved a well-publicized exchange of complaints. But Iranian behavior did moderate somewhat thereafter. Since his election, Obama has made several overtures to open a dialogue, particularly on Iran’s nuclear program. In 2009, Ahmadinejad initially agreed to a U.S.-backed proposal to a compromise deal on Iran’s controversial nuclear program, but then backed off when criticized at home from opponents on both the right and left.

In 2005, the hardline mayor of Tehran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, replaced reformist President Mohammad Khatami. Over the next five years, Tehran showed little interest in cooperating with the United States. Ahmadinejad wrote to both Bush and Obama, but neither responded. Bush authorized a series of talks in Baghdad in 2007 between the U.S. and Iranian ambassadors, which involved a well-publicized exchange of complaints. But Iranian behavior did moderate somewhat thereafter. Since his election, Obama has made several overtures to open a dialogue, particularly on Iran’s nuclear program. In 2009, Ahmadinejad initially agreed to a U.S.-backed proposal to a compromise deal on Iran’s controversial nuclear program, but then backed off when criticized at home from opponents on both the right and left.The Bonn talks

There is a popular perception in the United States that in the aftermath of 9/11, the United States formed a coalition and overthrew the Taliban. Actually, in the aftermath of 9/11, the United States joined an existing coalition which had been trying to overthrow the Taliban for almost a decade. The coalition consisted of India, Russia, Iran and the Northern Alliance. With the addition of American airpower, that coalition succeeded in ousting the Taliban.

The quick success in forming a successor regime was also thanks to this coalition, which met with others in Bonn to help forge a future for Afghanistan. The 10-day conference had representatives from the major Afghan opposition factions and from all principal regional states—Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran and the United States—that had been playing the so-called Great Game in Afghanistan for 20 years.

On two pivotal issues, Iran played a highly constructive role. At the conference, the United Nations circulated the first draft of the Bonn Declaration, which became Afghanistan’s interim constitution. It was the Iranian envoy who noted that the constitution had no mention of democracy. “Maybe a document like this ought to mention elections,” he suggested. The Iranian delegation also proposed that the document should commit the Afghans to cooperate against international terrorism.

On two pivotal issues, Iran played a highly constructive role. At the conference, the United Nations circulated the first draft of the Bonn Declaration, which became Afghanistan’s interim constitution. It was the Iranian envoy who noted that the constitution had no mention of democracy. “Maybe a document like this ought to mention elections,” he suggested. The Iranian delegation also proposed that the document should commit the Afghans to cooperate against international terrorism.On the last night of the conference, all major elements had been decided—except who was going to govern Afghanistan. The Afghan factions had agreed on the interim constitution, but they were still arguing about the composition of a new coalition government. The Northern Alliance insisted on occupying 18 of the 26 ministries; the other Afghan factions insisted that this was too many.

Again, Iran made a major contribution to forge a solution. U.N. Negotiator Lakhdar Brahimi assembled representatives from Russia, India, Iran and the United States, the four countries that had supported the Northern Alliance. For two hours, the four envoys pressed Northern Alliance representative Younnis Qanooni to give up several ministries. Qanooni remained obdurate. Finally, the Iranian envoy took him aside and whispered to him for a few moments. The Northern Alliance envoy returned to the table and said, “Okay, I agree. The other factions can have two more ministries. And we can create three more, which they can also have.” Four hours later, the Bonn Agreement was formally adopted. Ten days thereafter, Hamid Karzai was inaugurated in Kabul as the head of the new Afghan government.

Further cooperation

In early 2003, Japan held an international conference to raise money for Afghan reconstruction. Iran pledged $500 million in assistance. The American pledge, by comparison, was $290 million.

At the January conference, Iranian diplomats approached U.S. representatives bilaterally and through the Japanese government to express an interest in broadening their dialogue with the United States to include issues beyond Afghanistan. But in his first State of the Union address days later, President Bush characterized Iran, along with Iraq and North Korea, as an “axis of evil.” He threatened all three states with preemptive military action intended to halt their acquisition of weapons of mass destruction.

The Iranian regime nevertheless persisted in its efforts to expand cooperation with the United States. In March 2002, Iranian and American representatives met bilaterally on the fringes of yet another multilateral meeting about Afghanistan in Geneva. The Iranian delegation included a uniformed general who had been the commander of security assistance to the Northern Alliance throughout its insurgency campaign against the Taliban. The general said that Tehran was prepared to participate in an American-led program to raise and train a new Afghan national army. As part of this effort, he explained, Iran was prepared to house, pay, clothe, arm and train up to 20,000 Afghan troops in a broader program under American leadership.

The offer was briefly considered by Secretary of State Colin Powell, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice. But no positive decision was made, and the Iranians never received a response.

The Iraq invasion

In June 2003, three months after the American invasion of Iraq, Iran made an even more sweeping offer designed to address the full range of issues dividing the two countries. The proposal came from the Iranian foreign ministry; it was transmitted by the Swiss government, which represented American interests in Tehran in the absence of a U.S. Embassy.

The American invasions, first of Afghanistan and then of Iraq, had left the Tehran regime both grateful and fearful. They were grateful that the United States had removed their two principal regional opponents—the Taliban and President Saddam Hussein. But they were also nervous that Iran might be next. American troops were by then deployed to their north in Central Asia, to their east in Afghanistan, to their south in the Gulf and to their west in Iraq. Iran was virtually surrounded.

The American invasions, first of Afghanistan and then of Iraq, had left the Tehran regime both grateful and fearful. They were grateful that the United States had removed their two principal regional opponents—the Taliban and President Saddam Hussein. But they were also nervous that Iran might be next. American troops were by then deployed to their north in Central Asia, to their east in Afghanistan, to their south in the Gulf and to their west in Iraq. Iran was virtually surrounded.While these developments encouraged Tehran to improve relations with the United States, they had the opposite effect in Washington. Rapid victories, first in Afghanistan and then in Iraq, had made the U.S. government confident—and somewhat overconfident—about its successes and future influence in the region. The Bush administration therefore saw no rush to deal with Iran, and failed to respond to the Iranian overture.

The Baghdad talks

For several years after the 2003 offer, Iran’s position strengthened, while the U.S. military position weakened and its diplomatic leverage diminished. In 2001 and 2003, Tehran feared that the United States might invade Iran and overthrow its regime. By 2004, this fear had receded, as American troops became bogged down battling rising insurgencies in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

In August 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad replaced Mohammad Khatami as president. Hardliners replaced reformers in the foreign ministry and other key national security posts. Despite his tougher language on the United States, Ahmadinejad did not prove personally adverse to contacts with the American leadership. He wrote a letter to President Bush, full of tendentious religious references, and subsequently sent a congratulatory message to Barack Obama on his election as president. Neither of these missives received a response.

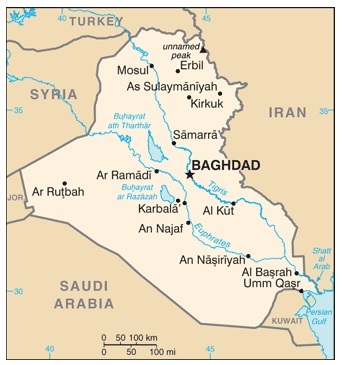

In 2007, the United States faced steadily mounting violence in Iraq, which Iran was partly responsible for feeding. The Bush administration authorized Ambassador Ryan Crocker in Baghdad to meet with his Iranian counterpart in trilateral talks hosted by the Iraqi government. Three sessions were held in May, June and August of 2007.

The meetings consisted largely of an exchange of complaints. No agreements resulted. But Iran’s support for extremist Shiite militia groups—a major U.S. complaint—did begin to moderate somewhat. Aggressive steps by the U.S. military to limit Iranian activity may have been a more important factor. So was pressure from the Shiite-led Iraqi government on Tehran. Nevertheless, the Baghdad talks, while entirely unproductive on the surface, at least did no harm. They may even have contributed to more restrained Iranian behavior.

Obama and engagement

When he took office in 2009, President Obama made several attempts to follow through on a campaign promise to try and engage with Iran and other rogue regimes. But he also sought to bypass the provocatively outspoken Ahmadinejad, who had written to him after his election. Obama instead wrote to the supreme leader, who ultimately makes all major domestic and foreign policy decisions. (The Clinton administration had tried the same tactic in reverse more than a decade earlier. It addressed overtures to then President Khatami and took a more critical position toward the supreme leader. That effort yielded little.)

When he took office in 2009, President Obama made several attempts to follow through on a campaign promise to try and engage with Iran and other rogue regimes. But he also sought to bypass the provocatively outspoken Ahmadinejad, who had written to him after his election. Obama instead wrote to the supreme leader, who ultimately makes all major domestic and foreign policy decisions. (The Clinton administration had tried the same tactic in reverse more than a decade earlier. It addressed overtures to then President Khatami and took a more critical position toward the supreme leader. That effort yielded little.)Obama made an initial overture to the Iranian people and government in a broadcast on the Iranian new year in March 2009. He sent two private messages to Ayatollah Khamenei. The State Department also announced that it was inviting Iranian diplomats to various U.S. Embassy Fourth of July celebrations, only to revoke the invitation a few days later in reaction to rising controversy in Iran over the disputed reelection of Ahmadinejad.

In the fall of 2009, senior U.S. and Iranian officials met briefly in Europe for multilateral talks on Iran’s controversial nuclear program. The American and Iranian envoys talked briefly on the sidelines of the meeting. Those larger talks produced a tentative interim agreement, which Ahmadinejad initially endorsed. Iran subsequently pulled back from the deal due to opposition from both conservative quarters and the reformist opposition.

Nuclear Negotiations

In 2013, Hassan Rouhani was elected President of Iran. He appointed Mohammad Javad Zarif as foreign minister. Zarif had been the principal architect of the 2001 and 2003 overtures to Washington, and subsequently Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator with the European Union. His appointment signaled a renewed attempt to open communication with Washington and find some areas of accommodation.

In November 2013, Iran and the world’s six major powers – Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States – reached an interim agreement on Iran’s nuclear program. Zarif and Secretary of State John Kerry held frequent bilateral talks in the months of negotiations that followed.

By 2015, the dialogue between Washington and Tehran had focused almost exclusively on arrangements to limit Iran’s nuclear program. Neither side was ready for overt cooperation on other issues, such as Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. But quiet conversations had taken place.

Trendlines

- Having reached a final nuclear deal, the United States and Iran are likely to gradually extend their dialogue to other issues. But both sides will have to contend with domestic opposition to greater engagement.

- Some level of agreement between Washington and Tehran will be essential to any effort to defeat the Islamic State, end the civil war in Syria and prevent the complete disintegration of Iraq.

James Dobbins, a former U.S. Ambassador and assistant secretary of state, directs the RAND Corporation’s International Security and Defense Policy Center and was a senior official at the Bonn talks with Iran.

Photo credits: Ahmadinejad via President.ir; U.N. logo via Wikimedia Commons [public domain]

This chapter was originally published in 2010, and is updated as of August 2015.