Interview with Nasser Hadian

How has the debate over the nuclear deal played out in Iran?

There are four major reactions to the deal among Iran’s political elites.

First, there are those who support the deal unconditionally, because they are tired of the economic and political situation in Iran. They want to normalize relations with the rest of the world. They believe that the costs of Iran’s nuclear program outweigh the benefits, so they back the deal no matter what. For them, the content of the deal – meaning the weight or composition of what was given and taken – is not all that important.

Second, there are those who support the deal, but with conditions. They do not necessarily think the deal was balanced in terms of content--and what each side received. But they think the strategic achievements that would result from the deal are worth the costs. So they support it.

Third, there are those who are critical of the deal, but have legitimate reasons for opposing it. They think it would have been possible to get a better deal from Iran’s perspective.

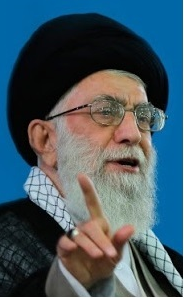

Fourth, there are those who oppose the deal unconditionally – not just this deal, but any deal. People who fall in this group have a wide range of reasons for opposing the deal. Some take this stance because they do not believe the United States is trustworthy. Others have issues with the nature of the American political system. Some also oppose any deal because it threatens their personal interests. They would like the hostile relationship with the United States to continue because they are benefiting from it in some way. Another group opposes the deal for ideological reasons. Any rapprochement with the United States would run counter to their beliefs.

Others worry about what might happen if the current situation changes. They might be suffering, but they are used to the way things are. They are concerned about what changes the deal might bring. Finally, some people are against the deal because they oppose the political system in Iran. They feel that the deal strengthens the regime and its chances for survival.

What would happen if Congress disapproves the deal?

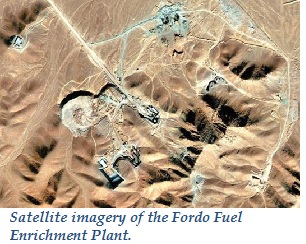

If there’s no deal, all political elites – except those who support the deal unconditionally – may ask for a return of the nuclear program. That could mean increasing the number of centrifuges, operating second-generation centrifuges, resuming uranium enrichment up to 20 percent, and resuming activities at Fordow [enrichment facility]. This could all happen very quickly. But Iran would probably not go to the extreme of expelling inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency or violating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

If there’s no deal, all political elites – except those who support the deal unconditionally – may ask for a return of the nuclear program. That could mean increasing the number of centrifuges, operating second-generation centrifuges, resuming uranium enrichment up to 20 percent, and resuming activities at Fordow [enrichment facility]. This could all happen very quickly. But Iran would probably not go to the extreme of expelling inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency or violating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).If Congress disapproves of the deal, Iran could well be in a better situation, both domestically and internationally, than it was before the negotiations. Iranians believe that President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif negotiated rationally and offered significant concessions. So the Iranian government could be in a stronger position in the eyes of many Iranian citizens, even if the deal falls through.

Additionally, those who hold negative views of the United States – particularly the Supreme Leader – could be vindicated. He and many others have insisted that Iran cannot trust the United States. They could argue that although Iran gave up significant concessions, the United States still would not comply with its side of the deal.

Additionally, those who hold negative views of the United States – particularly the Supreme Leader – could be vindicated. He and many others have insisted that Iran cannot trust the United States. They could argue that although Iran gave up significant concessions, the United States still would not comply with its side of the deal.Iran may also be better off internationally. Russia and China have perceived Iran as serious in its outreach to resolve the nuclear dispute. Europe may find it hard to sustain sanction too. Several senior European officials have visited Iran since the July 14 agreement. So Iran could improve its standing in the international community if the United States – and specifically Congress – rejected the deal.

If rejection of the deal is followed by a military attack, Iran may then decide to weaponize its nuclear program. Right now, only a small minority of Iranians support weaponization, although that could change if Iran is attacked. Nothing would be a stronger radicalizing force in Iran than military action.

If the deal is not implemented, would Iran return to the negotiating table?

It’s wishful thinking that Iran might return quickly to the negotiating table. The idea that America cannot be trusted would probably be ingrained in the Iranian psyche for the foreseeable future. I would go as far as to say that the impact of Congress not allowing the deal to proceed would be similar to the 1953 coup. In other words, the impact of rejecting the deal would not fade in just a couple years. It would shape the Iranian mindset for a very long time. And then a major question would loom: With whom Iran should eventually negotiate – the administration, Congress, or party leaders?

One alternative scenario is possible, however. Iran might return to the negotiating table under very different conditions – if it has 40,000 centrifuges and can also operationalize second-generation centrifuges. Its uranium stockpile could then increase to 25,000 kilograms or 30,000 kilograms. Iran could also have 1,000 kilograms of uranium enriched to 20 percent. It might even try to enrich uranium up to 60 percent or 65 percent. Iran might also try to finish and operationalize the heavy water reactor at Arak. That could happen no sooner than 18 months to two years after it resumes its program, which was curtailed during the 20 months of diplomatic negotiations. Iran may continue to suffer under sanctions, but greater capabilities could give it more leverage in future diplomacy.

One alternative scenario is possible, however. Iran might return to the negotiating table under very different conditions – if it has 40,000 centrifuges and can also operationalize second-generation centrifuges. Its uranium stockpile could then increase to 25,000 kilograms or 30,000 kilograms. Iran could also have 1,000 kilograms of uranium enriched to 20 percent. It might even try to enrich uranium up to 60 percent or 65 percent. Iran might also try to finish and operationalize the heavy water reactor at Arak. That could happen no sooner than 18 months to two years after it resumes its program, which was curtailed during the 20 months of diplomatic negotiations. Iran may continue to suffer under sanctions, but greater capabilities could give it more leverage in future diplomacy.Nasser Hadian is a professor of political science at the University of Tehran.

Photo credits: U.S. State Department via Flickr, NuclearEnergy.ir, Khamenei.ir

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org