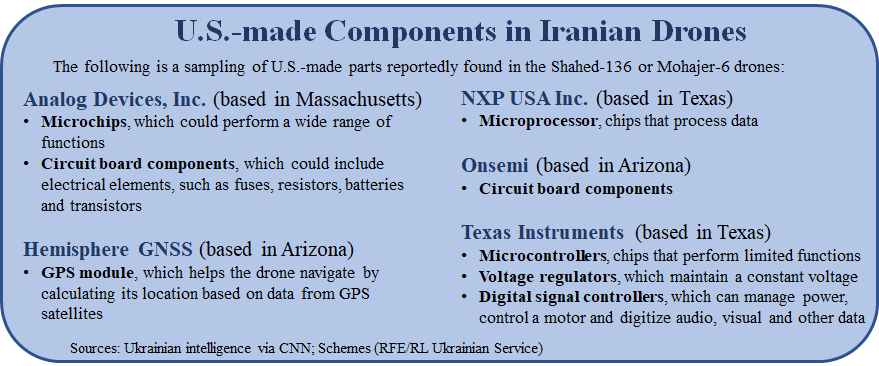

The majority of components in Iran’s drones—including microchips and GPS modules—were made in the United States, which is supporting Ukraine. The components, used for functions ranging from navigation to data processing, have been traced to two Iranian suicide drones—the Shahed-131 and Shahed-136—and the Mohajer-6, a drone that can conduct both strikes and reconnaissance.

After Iran exported drones to Russia for the Ukraine war in 2022, the White House established an interagency task force — including the departments of Commerce, Defense, Justice, State and Treasury — investigate how Iran obtained U.S.-made parts. The following is an interview with Gregory Allen, former Defense Department expert now a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Why has Iran used U.S.-made components? How much of the two drone systems – the Shaheds and the Mohajer—are made up of U.S. components?

Iran uses U.S.-made components for three main reasons. First, they are generally high quality. The Soviet Union famously tried to produce its own computer chips, but the quality was poor, and the failure rate tended to be high. The Soviet Union developed an extensive reverse engineering program to copy the more reliable U.S. products.

Second, U.S. products are compatible with many electronics made elsewhere. Using U.S.-made parts can save Iranian engineers from having to develop potentially expensive or complicated custom solutions. And a huge body of engineering documentation and expertise on how to use U.S.-made components is available to Iran’s drone manufacturers.

Third, U.S.-made components – often mass-produced and relatively inexpensive – are widely available in the commercial market.

The majority of components in the drones used by Russia against Ukraine appear to be U.S.-made. Some 77 percent of parts in one Shahed-136 were U.S.-made, according to Ukrainian intelligence. They were produced by 13 American companies. The other components were made in Canada, China, Japan, Switzerland or Taiwan. Conflict Armament Research (CAR), a British organization, examined four UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles), including one Shahed-131 drone, two Shahed-136s drones and one Mohajer-6 drone. Some 82 percent of their components were U.S.-made. At least, that’s what appears to be the case from the information that is publicly available. One important caveat is that sometimes counterfeit operations will falsely label their products “made in America” or include the logos of well-known international companies, when in reality they are just reverse-engineered copies illegally made elsewhere.

What did these components do?

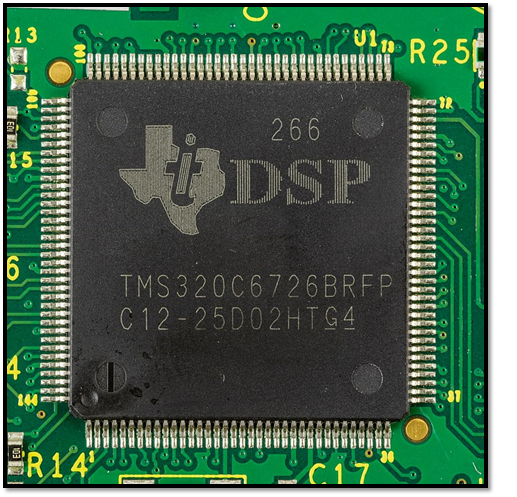

The U.S.-made components perform important functions, such as data processing and navigation. Some of the components are computer chips, which broadly fall into two categories – logic chips, which perform computations, and memory chips, which store data. Logic chips vary in sophistication. Central processing units (CPUs) act like brains which can control all or most of a drone’s systems. Other chips may perform limited functions, such as telling a wing or fin to turn when it encounters wind resistance. Many of the components are simple electronic parts that can be found in consumer goods.

How did Iran get these parts? Were U.S. companies aware that their parts have been sold to Iran? Why did they not stop them?

The U.S. companies probably are not aware of exactly how their parts reached Iran. These kinds of components, which are in widespread commercial use, are routinely sold to overseas distributors. Companies usually have large compliance departments that thoroughly vet buyers of their products. Larger distributors, however, may sell to smaller distributors or resellers. The first few transactions may be legal sales to reputable entities, but the fourth or fifth sale down the line could go to a smuggler with links to the Iranian military. Compliance departments cannot do much to track parts sold years ago that could have changed hands several times.

The other problem is that companies are making thousands or even millions of chips. They are small and easy to smuggle. In December 2022, Chinese customs officials arrested a woman smuggling hundreds of semiconductors (microchips) inside a prosthetic that made her look pregnant. She may have been trying to avoid taxes, not export controls. Regardless, tracking each chip is extremely difficult, especially when Iran may need only a few thousand for its drones.

Were the U.S.-made components meant for military use? Were they considered “dual-use” – items like GPS that could be used for both civilian and military purposes—and therefore not automatically subject to export restrictions? How might these components be used for non-military applications?

Most of the components are not meant specifically for military use but could have military applications since they are so versatile. Military-related customers account for a tiny fraction of the market for such electronics, which can be used in factory robots, commercial airplanes and even consumer electronics.

For decades, the United States has restricted exports of many types of goods to Iran, especially dual-use items. So, most of these parts cannot be sold directly to Iranian companies. Iran, however, almost certainly has obtained parts through smugglers operating in countries where export controls may not apply.

How did Iran acquire the components? How difficult or easy might they have been to obtain? Were intermediaries involved? Does receiving payment for parts sold to Iran violate U.S. sanctions?

The parts were probably not difficult to obtain since they are so widely available. But Iran almost certainly would have had to rely on intermediaries. Selling items to Iran could violate U.S. sanctions, but individuals and firms doing business with Iran are aware of that risk. One plausible path for the parts could have been as follows:

- A U.S.-based company applied for a license to export technology to an authorized country

- The Department of Commerce granted the export license

- The company sold the parts to a reputable distributor abroad

- The distributor sold the items to another reseller and so on

- After a fourth or fifth transfer, the items might have reached a smuggler or shell company with links to Iran

How complicit have U.S. companies in inadvertently helping Iran? What more could they have done to track supply chains to ensure that their products did not end up in Iran?

The companies are not necessarily to blame. Sanctions and export controls on Iran have fluctuated since the 1980s. Some parts may have been sold during periods when U.S. restrictions were relaxed.

Also, U.S. companies already have rigorous compliance departments that investigate customers to ensure they not do business with Iran’s military. But the companies have limited capacity to track small, inexpensive items, like microchips, that are sold in mass quantities and often resold several times. Identifying Iranian shell companies is also difficult. Even the U.S. intelligence community has trouble tracking all the shell companies constantly popping up.

By March 2023, what has the U.S. government done to track U.S.-made technology eventually sold to adversaries under sanctions? What has it done to prevent export to bad actors? What more can be done?

The Bureau of Industry and Security, part of the Department of Commerce, tracks transactions. But it is a small agency with limited enforcement capacity. It uses old databases that are prone to crashing. The agency’s budget, when adjusted for inflation, declined for years until the fiscal year 2023 Congressional budget appropriations bill was passed. Most of the increase in that budget, however, was unrelated to export controls enforcement.

The Bureau of Industry and Security, part of the Department of Commerce, tracks transactions. But it is a small agency with limited enforcement capacity. It uses old databases that are prone to crashing. The agency’s budget, when adjusted for inflation, declined for years until the fiscal year 2023 Congressional budget appropriations bill was passed. Most of the increase in that budget, however, was unrelated to export controls enforcement.

The agency needs more analysts and modernized computer systems to face the enormous challenges posed by China, Russia, Iran and other adversaries. The bureau needs to invest in artificial intelligence to analyze billions of global transactions and catch more smugglers. Only computers, using techniques like machine learning, can efficiently check information across multiple databases. To take a simple example, no human is going to remember that a phone number listed on a Polish tractor manufacturer’s export license was previously linked to a Russian smuggling network. Computers can do that work easily, though.

Why has Iran sought foreign parts for drones instead of producing them at home?

For Iran, sourcing parts from abroad is much cheaper than building factories to produce them. Instead of smuggling microchips, Tehran would need to smuggle equipment for manufacturing them. That would be significantly more difficult because manufacturing equipment is large and more easily tracked.

Iranian engineers would also need training on how to use and maintain the equipment, and spare parts might be needed from abroad. Also, the potential market for Iranian parts would probably be small, so production costs could be high. U.S.-made products, in contrast, are often inexpensive because they are made in enormous quantities.

How difficult would it have been for Iran to find alternatives to U.S. parts? What companies in other countries have sold parts that ended up in Iran?

Iran could conceivably find alternatives to U.S. parts, but they could be more expensive or less reliable. A lot of the microchips reportedly used in Iran’s drones employ technology that came out years ago. Less sophisticated chips may not be very difficult to replicate. Iran could potentially turn to Chinese companies with the relevant equipment to make them.

Iran has reportedly imported parts for the Mohajer-6 – including engines, cameras and motors – from several European and Asian companies, including:

- Engines produced by BRP-Rotax GmbH & Co KG, an Austrian subsidiary of the Canadian multinational Bombardier Recreational Products.

- Cameras produced by RunCam Technology based in Hong Kong.

- Servomotors, which allow drones to maneuver, produced by Tonegawa-Seiko Co. based in Japan.

To what extent has this been a global problem?

This problem extends far beyond Iran and the United States. Russia and China are also engaged in extensive efforts to acquire Western technology in violation of export controls. Their militaries and smuggling networks use increasingly sophisticated methods to obtain electronics.

Has Iran used U.S.-made parts in other weapons systems? Which ones? How long has Iran been illicitly obtaining U.S. technology for military use?

Iran has been using smugglers to obtain U.S.-made parts for decades, in part to repair aging military equipment purchased under the monarchy, when it was a U.S. ally. In the 1970s, oil-rich Iran bought U.S. military equipment worth billions of dollars. Relations soured after the 1979 revolution and the seizure of the U.S. Embassy and 52 diplomats by Iranian students. But Iran desperately needed spare parts for tanks, fighter jets and attack helicopters after Iraq invaded in 1980. Since then, Iran has used smugglers and arms dealers to fulfill its needs.

As of 2023, Iran was still using some of the U.S. equipment, including Vietnam War-era fighter aircraft. The vintage planes have been prone to failures. In 2022, an F-5 jet crashed into the wall of a school in Tabriz. The two pilots and a civilian on the ground were killed.