Hadi Semati is a former professor in the faculty of Law and Political Science at Tehran University and a former scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is now an independent analyst.

What is the state of Iran’s reformist faction—which had popular support under President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) and President Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021)—since the election of President Ebrahim Raisi in 2021?

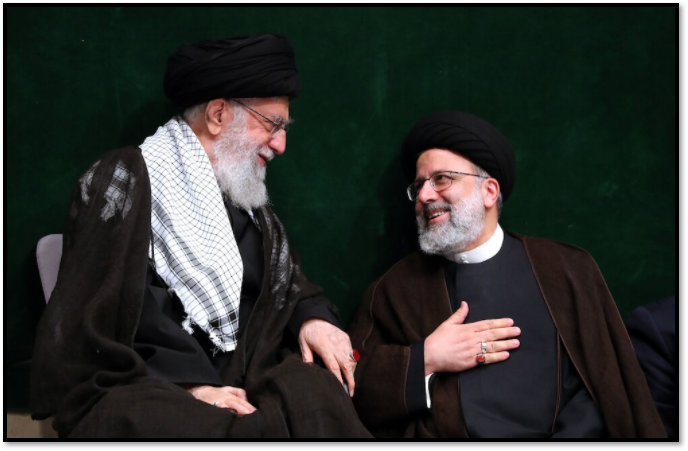

The reformists have been incapacitated for years. Many leaders have been sidelined politically, imprisoned, put under house arrest and forbidden from speaking in public. Under constant threat and intimidation, many have gone silent. The authorities have pushed nearly all of them out of electoral politics by disqualifying them from running for office. Raisi’s election in 2021 cemented hardline control over all three branches of government – the executive branch, the judiciary, and parliament.

The reformist movement, however, is not dead. Ironically, it is still the most organized political faction compared with conservative and hardline factions. More importantly, their ideas – such as expanding social and political freedoms – are still alive and appeal to the general public.

In 2022, protestors called for the downfall of the Islamic Republic. But many Iranians prefer gradual and genuine reform rather than abrupt changes, especially instability that could lead to violence. If the reformists get an opportunity to renter politics and can offer a viable pathway to changing the status quo, they could become a potent political force again. Given their experience, they could mobilize to change popular sentiments about reform.

What does the status of the reform movement reflect about politics in Iran today?

The weakness of the reform movement reflects how the state has narrowed the political space. The regime feels a greater threat from reformists than from protesters who call for regime change, even though reformists are non-violent and want to work within the framework of the Islamic Republic. Many conservatives understand that the reformist views are more in line with the majority of the public, they just don’t want to admit it or lack the courage to initiate some of those reforms themselves.

The Islamic state has, however, allowed a modicum of space for discourse in the media. In 2022, state television—the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting—produced a few talk shows critical of the status quo. Panelists openly discussed what should be done to solve economic, social and political problems. In newspapers and on news websites, reformists have also discussed their proposals for change.

Who are the main leaders or chief advocates of reform in Iran today? What is their agenda? Are there any still in government or parliament? How many are in parliament?

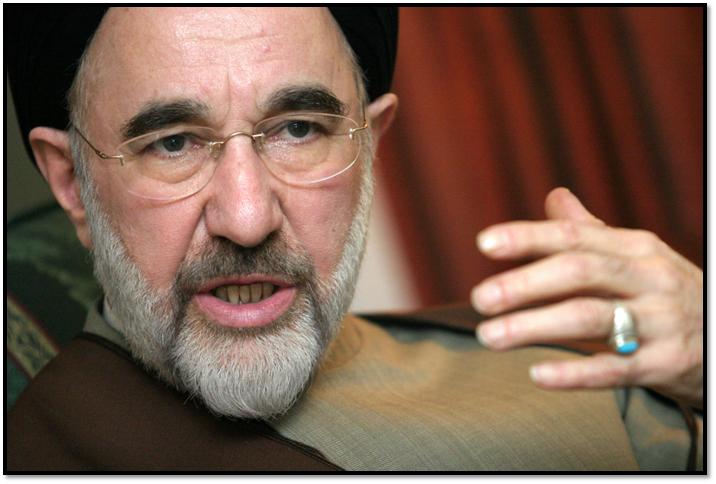

Reformist leaders have remained loyal to the revolution, despite their poor treatment by the government. Former President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) is still the de facto leader or spokesperson of the broader movement. Authorities have tried to isolate him since the disputed 2009 presidential election. Khatami had supported Mir Hossein Mousavi, the reformist candidate who lost to incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013). Khatami subsequently questioned the results and called for a referendum on the legitimacy of the government. He accused officials of using “fascist and totalitarian methods” to silence political opponents.

The judiciary then banned the media from publishing Khatami’s name or image. He was not placed under house arrest, but security forces limited his movement. Khatami, however, continued to call for reform through video messages and statements on social media. Freedom and security should not be placed “in opposition to one another and, as a result, freedom is trampled under the pretext of maintaining security, or that security…is ignored in the name of freedom,” he said in a statement about the protests in December 2022.

Mir Hossein Mousavi, a former prime minister (1981-1989) and 2009 presidential candidate, is a symbolic figurehead to the movement. His protest of the 2009 election results sparked the Green Movement demonstrations that brought millions of people onto the streets across Iran. He was placed under house arrest in 2011 for his role in the opposition. The government labeled Mousavi and his supporters “seditionists.”

Mousavi has periodically issued statements critical of the government published on an opposition Persian-language website. In 2019, he compared Khamenei to the shah. During protests over an abrupt hike in gas prices, he condemned the government crackdown, which killed hundreds. Mousavi likened the deaths to the killings during the run-up to the 1979 revolution.

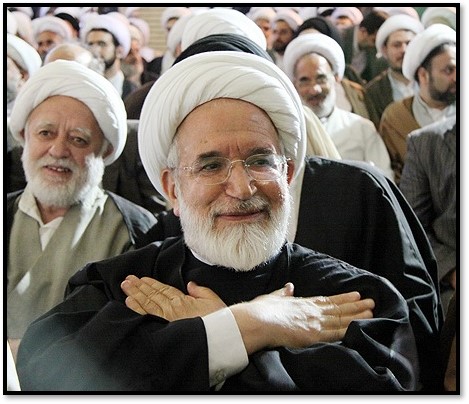

Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of parliament (1989-1992 and 2000-2004), is another nominal reformist leader. Karroubi came in fourth place in the 2009 presidential election, according to the official results, which he disputed. He was also placed under house arrest in 2011.

In subsequent open letters to the public, Karroubi bitterly criticized the government. In 2016, he called on the “the despotic regime” to grant him a public trial so that he could defend himself. In 2018, Karroubi accused elites of corruption and mismanaging the economy. He even called out Khamenei. “You have been Iran’s top leader for three decades, but still speak like he’s in the opposition,” wrote Karroubi. “I strongly urge you to create the grounds for reform in order to make all the sectors in the country accountable to the people and lawful institutions.”

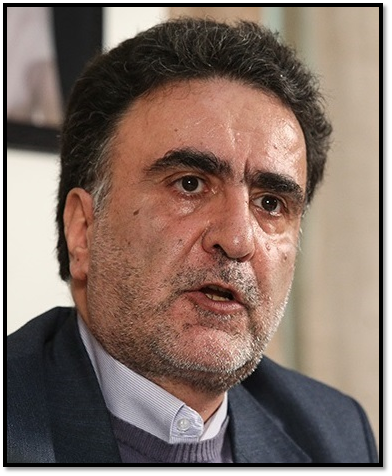

Mostafa Tajzadeh, a former deputy interior minister and advisor during Khatami’s presidency, is a leading reformist politician. He was imprisoned after the 2009 presidential election and sentenced to six years in prison for “harming national security” and “propaganda against the state.” In 2014, another year was added to his sentence for additional charges. Tajzadeh was released in 2016 but did not retreat politically. He called on authorities to release Mousavi and Karroubi. In 2021, he registered to run for the presidency but was barred from running by the 12-man Guardian Council.

Tajzadeh has gone further than other reformist leaders by calling for more democracy and basic structural reforms, including term-limits for the supreme leader and removing the powers of the Guardian Council to vet all candidates for all offices. He called for the Revolutionary Guards to be stripped of any direct involvement in political and economic life. He proposed normalization of relations with the United States. In July 2022, he was detained for allegedly “undermining national security.” In October, he was sentenced to five years for “collusion against national security,” two years for “spreading lies,” and one year for “propaganda against the state.“

In the 2020 parliamentary election, the vast majority of reformist candidates, including former lawmakers, were barred from running, so conservatives won in landslides. So only about a dozen of the 290 members of parliament were reformists. In 2022, the only prominent reformist member of parliament was Masoud Pezeshkian, who has represented the northwestern city of Tabriz since 2008. He was the deputy speaker between 2016 and 2020. A heart surgeon, he was health minister (2001-2005) under Khatami.

How have reformists reacted to the protests in 2022? Have they had any impact on the protests or protesters?

On October 1, Mousavi urged the security forces to side with the people. “The powers vested in you are for defense of the people, not their repression, for protection of the oppressed, not service to the powerful and mighty,” he said in a statement. “The hope is that you will stand on the side of truth and the nation. Your duty is secure the peace for the millions and especially the downtrodden, and not to consolidate the power of oblivious officials.”

Khatami’s responses were more cautious. In an Instagram post on October 27, he urged officials to “hear the voice of criticism” and provide “material and spiritual satisfaction” for the people. In another post on November 14, Khatami warned that overthrowing the government was neither possible nor desirable. He instead called for a “self-correction of the system.” But in a December 6 message on Telegram, he went further. The slogan of the protests – woman, life freedom – is “a beautiful message that shows movement towards a better future,” Khatami said. “Freedom must not be trampled on in order to maintain security.”

Over the first three months of protests, reformist parties also appealed to the government to heed the protestors. Some leaders spoke out against the crackdown. But they largely refrained from taking to the streets to avoid being barred from political activities, which opened them up to criticism. On November 9, the Reform Front, an umbrella of parties aligned with Khatami called for a public referendum to address the unrest triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini on September 16. The group urged “innovative changes” and a national dialogue. But these statements have had little to no impact on the ground. The protesters have largely moved on from the reformists and do not think they are relevant.

How do reformists relate to Generation Z, which fueled the protests launched on September 16, 2022?

Reformists empathize with the grievances of Generation Z to some extent, but the gap between the two groups is huge. This is part of a broader generational change in society. The majority of the population was born after the 1979 revolution. Many of the youth do not know the reformist leaders, who are primarily elderly men. In 2022, Khatami turned 79, Mousavi turned 81, and Karroubi turned 85. Their generation, which produced the revolution, wanted to create a utopian state based on the principles of independence, freedom and social justice. They were concerned about the working class.

In stark contrast, Zoomers are more individualistic. They have dramatically different priorities because they grew up with the internet and feel connected to the outside world. Zoomers want the same freedoms that their peers in the West take for granted. They are concerned with finding decent jobs or starting their own businesses, and traveling abroad. Many are more focused on their social networks and hobbies as opposed to social movements or political parties.

The protests, however, have shown that the student movement is not dead. Universities have historically been the engines of political change in Iran, especially in the runup to the 1979 revolution. In 2022, demonstrations were held at more than 140 campuses in all 31 provinces. The renewed campus activism, after a decade of declining political participation among youth, demonstrated how fast dynamics on the ground can change.