Many Iranian women have opposed the Islamic dress code since it was made mandatory in 1981. Why did the issue reach an inflection point in 2022?

The killing of Mahsa Jina Amini while in state custody in September 2022 reverberated throughout Iran. At age 22, the young woman embodied the nation's future—a future stifled by a government that exercises its power through suppression and unchecked authority. The somber event galvanized many Iranians, particularly young people and women, who demonstrated their refusal to remain silent while the government employed violence and detainment to perpetuate its rules. Women played a much more prominent role in the 2022 movement compared to previous rounds of protest, such as the 2019 demonstrations that were triggered by a gas price hike and then evolved into anti-state protests. Women – especially young women, including high school girls – led the protests and posed a formidable and unprecedented challenge to the regime.

The governing authorities of the Islamic Republic have turned the hijab, which should be a matter of personal choice, into an instrument of political subjugation. Since its imposition, Iranian women have resisted, both subtly and overtly. After the large-scale street demonstrations in 1981, women may have been cowed by the government’s violent response, but progressively they pushed boundaries. Prompted by the outrageous death of Amini in September 2022, thousands of women took the audacious act of shedding the hijab altogether. Hundreds of Iranians were killed by state security forces during the heights of the protest movement.

How was the hijab issue reflective of a broader struggle for personal freedoms?

Underpinning the movement was the slogan, "Woman, Life, Freedom," which encapsulated the profound deprivations that many Iranians endured over the decades—deprivations concerning women's rights, the autonomy to shape one's life according to personal prerogatives, and the overarching principle of freedom.

Concurrently, the refrain "Death to the dictator!" resounded as an unequivocal rejection of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the impunity that pervaded the government’s actions. The slogan reflected the populace's ardent desire for a responsive government—one attuned to the needs of the people. The Islamic Republic has persistently demonstrated either indifference or overt disregard for the populace's aspirations. The erosion of trust in the system has led many people to seek a transformative alternative.

Why was the issue of hijab so sensitive for the theocratic government?

The enforcement of the forced-hijab law was a foundational tenet of the Islamic Republic. To retract this mandate would necessitate acknowledging both the unpopularity and ultimate failure of the revolution.

After the 1979 revolution, authorities wanted women to embody their vision of revolutionary and Islamic ideals. Consequently, they imposed the use of dark, tent-like hijabs called “chadors.” Women were treated as second-class citizens in both legal frameworks and practicality; the theocracy imposed restrictions on marriage, divorce, employment, inheritance, and political participation.

Although Iranian women opposed to the laws confronted severe violence, they found a way to tangibly assert agency over their bodies in their daily behavior. Many women rejected the chador and the conservative values associated with it. Gradually, women began reclaiming control through their attire, consistently pushing boundaries of acceptability within the Islamic Republic. In the 1990s, many women started wearing the more form-fitting manteau (overcoat) and a headscarf, which allowed more hair to be visible.

What has the debate on enforcement been like among government officials? Who were the main proponents of strict enforcement?

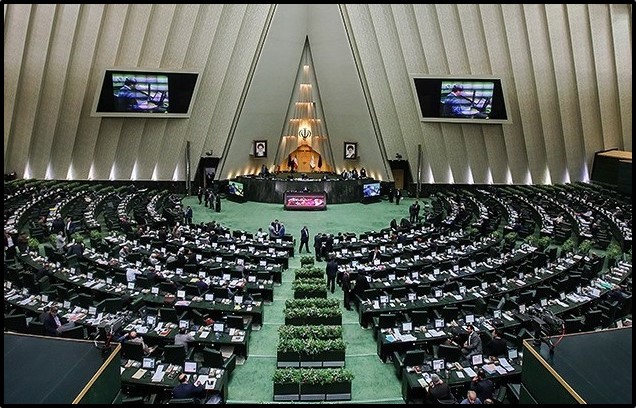

Public support for the forced-hijab law has dwindled, even according to the government’s own data. By the early years of the 21st century, some 49 percent of Iranians believed hijab to be a personal choice, not a mandate, according to a study released by the centrist government of Hassan Rouhani in 2018. The report was based on surveys conducted by the Iranian Students Polling Association in 2006 and 2014 and may have underestimated the true opposition to the mandate. Also in 2018, the Parliamentary Research Center suggested a revision of the law given widespread opposition. But Parliament, dominated by hardliners since the 2020 election, did not push through any reforms.

In the summer of 2023, after protests had died down, the government sought to increase penalties for women defying the dress code. Women already faced fines, arrests, or imprisonment for non-compliance. They could even be charged with prostitution or “promoting prostitution” if they advocated for a woman’s right to choose her attire. This offense carried a penalty of one to 10 years’ imprisonment.

The “Chastity and Hijab” bill, which a special parliamentary committee was debating in secret as of September 2023, would further exacerbate the discriminatory treatment of women. The legislation equated appearing in public without hijab—whether in person or on social media—with societal harm tantamount to “nudity.” The bill introduced various additional penalties, encompassing fines, banking restrictions, vehicle confiscation, travel limitations, online bans, and imprisonment.

The bill, which was expected to be approved by the powerful Guardian Council, would be implemented on a trial basis for three to five years. Parliament could make amendments and then make the law permanent. The changes would further perpetuate a climate of oppression and curtail personal freedom. All three branches of the government – Parliament, the judiciary and the presidency – broadly backed increased enforcement. Several influential conservative clerics asserted that the proposed bill didn’t go far enough.

How did the government’s enforcement of the mandatory dress code evolve after protests erupted in September 2022? What new tactics did it employ?

After the outbreak of nationwide protests, the so-called morality police, a branch of the police implicated in the killing of Amini, largely vanished from the streets. The government seemed to understand that the enforcers, in their ubiquitous white vans, would provoke even more intense public resentment.

As patrols subsided, more and more women appeared in public without the hijab. But the morality police forces were never disbanded, and the Iranian government later doubled down on its position, stepping up enforcement rather than acknowledging the undeniable surge of women's empowerment sweeping across Iran.

As of September 2023, not only were women being penalized through various methods for exercising their right to freedom of expression, but regular citizens were also being compelled to assist law enforcement efforts. For instance, they were required to deny services to women who didn’t adhere to hijab regulations, blocking access to banks, shops and restaurants. Business owners who failed to comply risked fines or even closure of their establishments. The government redeployed the morality police in July 2023 and announced plans to introduce heightened surveillance technologies for digitally tracking women not wearing the hijab.

These measures, marked by humiliation and severe repression, garnered widespread condemnation from human rights organizations. U.N. human rights experts denounced the “criminalization of refusal to wear a hijab” by the Islamic Republic of Iran as a blatant infringement upon freedom of expression.

What prompted the government to redeploy the morality police and step up its enforcement of the mandate?

Clerics and hardline officials spearheaded the initiative to reinstate the morality police, with minimal resistance encountered within the government. Backing the Islamic Republic inherently meant endorsing its policies. Within the government, speaking out against the mandatory hijab could be equated to condemning the entire state apparatus.

As for the timing of this redeployment, the government may have anticipated renewed protests coinciding with the anniversary of Amini's killing, along with the movement she ignited. By ensuring the readiness of its suppression mechanism, the government seemingly sought to swiftly quell any potential resurgence of street demonstrations.

How might the enforcement of the dress code contribute to future protests or unrest?

The dress code signified more than a mere set of clothing regulations; it embodied a legal construct that inherently discriminated against women. As the state further solidified its position, Iranian women stood unwavering against the prospect of regression. The “Woman Life Freedom” movement substantially reshaped the expectations of Iranians, particularly those under 35, who constituted the majority of the population and faced bleak prospects for their future.

“These protests will endure,” said a perceptive 15-year-old high school student from Mashhad, who shared her perspective with the Center for Human Rights in Iran in February 2023. “We've dismantled and constructed various aspects of our society. At the very least, a profound change has taken root within our minds. Returning to our previous state is inconceivable.”

She and her peers are poised to outlive and outlast the preceding generation of elder men governing Iran through coercion and violent aggression. These men perceived Iran through a lens that obstructed their view of the evolving reality, but the public demands for change ultimately threaten to consign them to the pages of history.

Jasmin Ramsey is the Deputy Director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran.