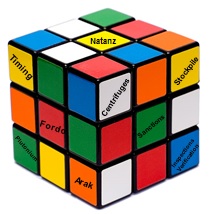

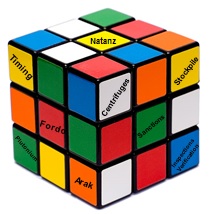

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.

CENTRIFUGES: Since 2002, Iran has built centrifuges to enrich uranium, which can fuel both peaceful energy and deadly bombs. Tehran claims it is only for medical research and energy. But Iran’s abilities far exceed its current needs; Russia provides fuel for Iran’s single nuclear reactor.

Iran now has about 19,000 centrifuges—up from less than 200 a decade ago. The vast majority of these are first-generation “IR-1” centrifuges, but Iran has begun installing much more sophisticated “IR-2” models. About 10,000 are enriching uranium at Iran’s two enrichment facilities, Natanz and Fordow; the rest are installed but not operating. The more centrifuges or the more advanced centrifuges Iran has, the faster it can enrich uranium.

A deal will try to reduce the number of Iran’s centrifuges. Outside experts suggest the goal could be to limit Iran to between 2,000 and 6,000 operating IR-1 centrifuges, and place constraints on research and development into more advanced machines.

ENRICHMENT: Uranium enriched to 90 percent is the purest form to fuel a weapon. Prior to the November 24 “Joint Plan of Action” (JPOA) interim nuclear deal, Iran was enriching up to 20 percent level; under the JPOA, enrichment has been temporarily capped at five percent or less.

A final deal could seek to limit enrichment to five percent or less.

STOCKPILE: The larger the stockpile of uranium gas, the faster Iran could produce fuel for a bomb. Iran had 447 kg of uranium enriched at 20 percent before the interim deal went into effect in January. It has since begun “neutralizing” its 20 percent stockpile by diluting 104 kg to 3.5 percent enriched uranium and converting another 287 kg into uranium oxide powder. As of May, Iran had an estimated 56 kg of uranium gas enriched at 20 percent. It is due to dilute or oxidize all its 20 percent uranium gas by July 20.

A deal could seek to limit the stockpile of 5 percent enriched uranium and require Iran to further reduce its stockpile of 20 percent uranium in oxide form. Iran may be allowed to keep some for research, but not enough to quickly build a bomb.

NATANZ: Iran’s primary enrichment facility includes three underground buildings, two of which are designed to hold 50,000 centrifuges, and six buildings built above ground.

A deal will try to limit the program at Natanz.

FORDO: The smaller, underground enrichment facility near Qom includes two halls; each could hold 1,500 centrifuges. Iran claims Fordow is to enrich uranium up to 20 percent— only for research. But skeptics contend the deeply-buried site, designed to survive aerial bombardment, is intended to take 20 percent enriched material from Natanz and enrich it to higher levels for use in a nuclear weapon.

A deal will try to end enrichment activities at Fordow, perhaps converting it to a research-only facility.

ARAK: The small heavy-water reactor, begun in the 1990s, is unfinished. Iran claims it is to produce medical isotopes and thermal power for civilian use. But the design would also produce plutonium that, if chemically reprocessed, could provide an alternative fuel to uranium for an atomic bomb. Nine kilograms of plutonium is enough material to fuel one or two nuclear weapons. After completion, Arak would need to run for 12 to 18 months to generate that much plutonium.

A deal will try to close Arak or redesign it in a way to substantially reduce plutonium output. A deal will also try prohibit Iran from building a reprocessing facility.

INSPECTIONS and VERIFICATION: Any deal will require considerable transparency into the nature and extent of Iran’s civilian nuclear infrastructure, as well as possible past military dimensions of its program. A deal will also involve extensive inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of Natanz, Fordow, Arak, centrifuge assembly facilities, uranium mines, research facilities—and possibly other sites—aimed at ensuring that Iran’s program remains solely for peaceful purposes.

It may also cover access to sites suspected of past work on bomb components, such as Parchin military base. And it is likely to require Tehran’s acceptance of the IAEA’s “Additional Protocol,” allowing inspections at both declared and undeclared sites—and maybe other intrusive measures.

IRAN’S RED LINES:

Iran has its own configurations for the Rubik’s Cube of a deal. They include:

- Preserving key elements of its nuclear program, including some uranium enrichment and research and development

- Protecting Iran's "right" under the Non-Proliferation Treaty to a peaceful nuclear energy program to alleviate the drain on its oil sources and fuel modern development

- Removing nuclear-related sanctions on Iran by the United States, European Union and United Nations

July 14 Update: Iran released the most detailed report to date explaining its practical needs for its nuclear program. It was posted on the quasi-official website NuclearEnergy.ir.

For more information, see:

Photo credits: Rubik's Cube by by Lars Karlsson (Keqs) (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons [edited by Iran Primer], President.ir

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.