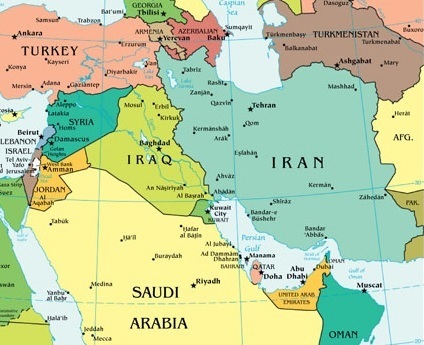

- Relations between Iran and Turkey have long been defined by mutual suspicion and competition, despite a 312-mile border that has remained unchanged since 1639.

- Close allies during the monarchy, relations soured after the 1979 revolution. Ankara felt threatened by Tehran’s ambitions to change the regional order. Iran in turn perceived Turkey as a close ally of the West and therefore potentially hostile.

- Adding to tensions, Tehran and Ankara have diametrically opposed worldviews: Turkey is a constitutionally secular state where the military is the self-appointed guardian of secularism. Iran is a theocracy in which Islamic law rules and clerics play decisive roles, including control over the military.

- Yet the two governments have cooperated when necessary, especially on energy and Kurdish issues. Relations improved after the 2002 election of Turkey’s Justice and Development Party, which has Islamist roots.

- The two countries have opposing positions on the Syrian civil war. Iran supports Bashar al Assad’s regime while Turkey seeks its removal. Yet they have managed their relationship with little acrimony despite this major difference.

In many ways, Turkey and Iran are mirror images of each other. They share geography, culture, religion and a long history of conflict and cooperation. They both straddle multiple geopolitical regions. Between the two, they span two continents and border five of the world’s most volatile regions—the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Balkans, Central Asia and the South Asian subcontinent. They are both descendants of empires with hegemonic histories that occasionally pitted them against each other. In the 16th century, Persia converted to Shiite Islam in part to distinguish itself from the Sunni caliphate of the Ottoman Empire. Both countries today are also profoundly insecure about real and imaginary enemies at home and abroad. As inheritors of great civilizations, they both feel their importance has been largely unappreciated.

In many ways, Turkey and Iran are mirror images of each other. They share geography, culture, religion and a long history of conflict and cooperation. They both straddle multiple geopolitical regions. Between the two, they span two continents and border five of the world’s most volatile regions—the Middle East, the Caucasus, the Balkans, Central Asia and the South Asian subcontinent. They are both descendants of empires with hegemonic histories that occasionally pitted them against each other. In the 16th century, Persia converted to Shiite Islam in part to distinguish itself from the Sunni caliphate of the Ottoman Empire. Both countries today are also profoundly insecure about real and imaginary enemies at home and abroad. As inheritors of great civilizations, they both feel their importance has been largely unappreciated. Iranian-Turkish relations became more confrontational after the Iran-Iraq war ended, in part because of ideological differences. Each viewed the other through the narrow prism of their secular-religious divide. The Turks were particularly suspicious of Iranian support for fundamentalist movements in Turkey. The Iranian ambassador to Ankara was declared persona non grata after he criticized the Ankara’s ban on Muslim women wearing headscarves in universities and government offices, and even participated in demonstrations against the ban. Ankara was also bitter about Iranian aid to insurgents in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which operated bases deep in Iranian territory. In 1991, Turkey detained an Iranian-flagged vessel on suspicion of carrying weapons destined for the PKK.

Iranian-Turkish relations became more confrontational after the Iran-Iraq war ended, in part because of ideological differences. Each viewed the other through the narrow prism of their secular-religious divide. The Turks were particularly suspicious of Iranian support for fundamentalist movements in Turkey. The Iranian ambassador to Ankara was declared persona non grata after he criticized the Ankara’s ban on Muslim women wearing headscarves in universities and government offices, and even participated in demonstrations against the ban. Ankara was also bitter about Iranian aid to insurgents in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which operated bases deep in Iranian territory. In 1991, Turkey detained an Iranian-flagged vessel on suspicion of carrying weapons destined for the PKK. Iran also slowly shifted its stance, particularly on the sensitive Kurdish question. After years of tolerating PKK activities in Iran, Tehran gradually began to prevent the movement’s access to its territory. Tehran’s policy shift emerged after a PKK affiliate, the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK), successfully attacked Iranian security forces. In response, Iran launched artillery strikes against both the PKK and PJAK in their hideouts in northern Iraq’s remote Qandil mountains. Iran’s new policy was a way to begin intelligence cooperation and ingratiate itself with Turkey; it was also a way to embarrass the United States, which occupied Iraq at the time but had been reluctant to militarily act against the PKK.

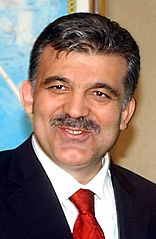

Iran also slowly shifted its stance, particularly on the sensitive Kurdish question. After years of tolerating PKK activities in Iran, Tehran gradually began to prevent the movement’s access to its territory. Tehran’s policy shift emerged after a PKK affiliate, the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK), successfully attacked Iranian security forces. In response, Iran launched artillery strikes against both the PKK and PJAK in their hideouts in northern Iraq’s remote Qandil mountains. Iran’s new policy was a way to begin intelligence cooperation and ingratiate itself with Turkey; it was also a way to embarrass the United States, which occupied Iraq at the time but had been reluctant to militarily act against the PKK. Turkey’s changed approach has been most apparent on Iran’s nuclear controversy. The Turks have historically been ambivalent about Tehran’s program. In 2010 President Abdullah Gül expressed misgivings about the Islamic Republic’s ultimate objectives. At the same time, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan publicly vouched for Tehran’s peaceful intentions on nuclear energy at a time the international community and Turkey’s allies expressed growing alarm about the dangers of Iran developing a nuclear weapon. Erdogan repeatedly argued that Iran’s program was not the real problem and instead tried to make Israel the issue, to the annoyance of the United States. This would prove to be an important psychological boost to Tehran since the central issue was its lack of compliance with international safeguards and rules.

Turkey’s changed approach has been most apparent on Iran’s nuclear controversy. The Turks have historically been ambivalent about Tehran’s program. In 2010 President Abdullah Gül expressed misgivings about the Islamic Republic’s ultimate objectives. At the same time, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan publicly vouched for Tehran’s peaceful intentions on nuclear energy at a time the international community and Turkey’s allies expressed growing alarm about the dangers of Iran developing a nuclear weapon. Erdogan repeatedly argued that Iran’s program was not the real problem and instead tried to make Israel the issue, to the annoyance of the United States. This would prove to be an important psychological boost to Tehran since the central issue was its lack of compliance with international safeguards and rules. Negotiations between Iran and the so-called P5+1 powers were reinvigorated following the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani and his appointment of Mohammad Javad Zarif as foreign minister. An interim agreement was brokered in November 2013. Turkish officials welcomed it, but said that it fell short of the 2010 agreement that Turkey and Brazil negotiated. “When we look at the positions [of the] P5+1 right now, Iran is still below the line we were able to bring in 2010, but we hope it will come to that line,” said Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu.

Negotiations between Iran and the so-called P5+1 powers were reinvigorated following the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani and his appointment of Mohammad Javad Zarif as foreign minister. An interim agreement was brokered in November 2013. Turkish officials welcomed it, but said that it fell short of the 2010 agreement that Turkey and Brazil negotiated. “When we look at the positions [of the] P5+1 right now, Iran is still below the line we were able to bring in 2010, but we hope it will come to that line,” said Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu.- Iran accounts for 20 percent of Turkey’s gas imports. But the Iranians have not been reliable partners. Twice in 2010, for example, cold weather forced Iran to indefinitely suspend deliveries, which led the Turks to look for alternative supplies.

- Trade between Turkey and Iran totaled $10 billion in 2008. Iran exported $8.2 billion in goods, mostly hydrocarbons. Turkey exported $2 billion. In 2009, Iranian exports to Turkey declined precipitously to $3.4 billion, although Turkish exports remained stable. Turkey’s exports to Iran represent no more than 2 percent of its total exports. By 2014, the volume of trade between Turkey and Iran had climbed to $13.7 billion.

- Turkey has the largest Kurdish population, estimated to be up to 18 percent of the population or 14.7 million. Iran has the second largest population, estimated at around 8 million.

- Turkey is one of the few countries Iranians can travel to without a visa.

- Iran and Turkey are members of the Economic Cooperation Organization, a 10-nation alliance created in 1985, with members stretching from Turkey through Central and South Asia. Tehran and Ankara are also members of the Developing-8, an association of mid-income Muslim nations created by the Turks in the 1990s.

Turkey and Iran have emerged as the two rival models for much of the Islamic world. They represent disparate ways of blending Islam and democracy. Turkey has engaged in gradual evolutionary change. The AKP’s Sunni Islamist roots notwithstanding, Turkey has generally adhered to secularism. Its foreign policy has become increasingly multi-faceted. It is already a member of the world’s most powerful military alliance, NATO, and is a candidate to join the European Union. It is a rising mid-level power. And its economic reforms have made it the 18th largest economy in the world.

Turkey and Iran have emerged as the two rival models for much of the Islamic world. They represent disparate ways of blending Islam and democracy. Turkey has engaged in gradual evolutionary change. The AKP’s Sunni Islamist roots notwithstanding, Turkey has generally adhered to secularism. Its foreign policy has become increasingly multi-faceted. It is already a member of the world’s most powerful military alliance, NATO, and is a candidate to join the European Union. It is a rising mid-level power. And its economic reforms have made it the 18th largest economy in the world. The Arab Spring – and the outbreak of Syria’s conflict in particular – began to complicate Turkey’s “zero problems” policy with its neighbors. In the 2000s, Erdogan and Syrian President Bashar al Assad were on good terms. But their relationship soured after Turkey and Iran supported diametrically opposed groups in Syria after 2011. Iran backed Assad, while Turkey sided with the largely Sunni opposition groups.

The Arab Spring – and the outbreak of Syria’s conflict in particular – began to complicate Turkey’s “zero problems” policy with its neighbors. In the 2000s, Erdogan and Syrian President Bashar al Assad were on good terms. But their relationship soured after Turkey and Iran supported diametrically opposed groups in Syria after 2011. Iran backed Assad, while Turkey sided with the largely Sunni opposition groups.- Turkey’s principal concern is the stability of the Iranian regime. President Ahmadinejad’s erratic behavior irritated Ankara, but the AKP government was not sufficiently offended to disrupt its bourgeoning ties with Tehran. Turkey welcomed Ahmadinejad’s replacement, Hassan Rouhani, when he came to office in 2013.

- Yet the current Turkish government—despite its sympathies and expectations of greater trade opportunities—is not an ally of Iran. It sees itself in a long-run competition with Iran for influence.

- The Arab Spring tumult has made Turkish foreign policy more sectarian. Turkey has been willing to associate itself with Sunni countries like Saudi Arabia and Qatar to the detriment of Iran’s regional allies, whether in Iraq or Syria.

- Turkey, nonetheless, may try to take advantage of sanctions relief as the nuclear deal with Iran is implemented. Turkish businesses will may try to make greater inroads into Iran. But Iran will likely continue to suspect Turkey of acting as a surrogate for Western interests.

- The biggest challenge facing Iran and Turkey is the fate of Bashar al Assad. If Assad were to fall to Turkey-backed Sunni opposition groups, it could have major implications for Turkey’s relationship with Iran.

Iranian Leaders React to Turkey Coup

Iranian leaders expressed strong support for Turkey’s elected government and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan following a failed coup by military officers. “These people should understand that the way of resolving the problems is democracy and respecting the nation’s vote,” said President Hassan Rouhani on July 17. In a tweet, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif added, “Turkish people's brave defense of democracy & their elected government proves that coups have no place in our region and are doomed to fail.”

On July 15, tanks entered streets in Ankara and Istanbul while attack helicopters and fighter jets strafed parliament and the intelligence headquarters. Uniformed soldiers attempted to take control of key sites, such as the Bosphorus Bridge. Social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook and Youtube, were blocked. Erdogan addressed the nation using FaceTime and his mobile phone, which was picked up by CNN Turk. He called on the Turkish people to take to the streets in support of the government. Amid the chaos, more than 200 people were killed and more than 1,400 people were injured. The coup faltered in the face after public demonstrations opposed to the takeover.

What the attempted coup in Turkey looked like https://t.co/RtHG97OX5v pic.twitter.com/8wSXs6pOln

— The New York Times (@nytimes) July 17, 2016

In the following days, authorities began a widespread crackdown on individuals suspected of having connections to the plotters. Nearly 20,000 members of the police, army, civil service, and judiciary were reportedly detained or suspended as of July 18.

Erdogan blamed the coup on low-ranking military officers and on Fethullah Gulen, a reclusive cleric who has been living in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania since 1999. Gulen, a rival of Erdogan’s, leads a popular movement called Hizmet that is thought to have a wide following in Turkey. The following are reactions to the attempted coup in Turkey by Iranian leaders.

President Hassan Rouhani

“We are in a region where unfortunately some people still assume they can change the power structure through a coup; or overthrow a government that has come to the power through the polls using tanks, fighter jets and helicopters,”

“We are in a region where unfortunately some people still assume they can change the power structure through a coup; or overthrow a government that has come to the power through the polls using tanks, fighter jets and helicopters,”

“These people should understand that the way of resolving the problems is democracy and respecting the nation’s vote.”

“Today is the day when issues can be settled at ballot boxes, and people can make their voice heard through their votes.”

—July 17, 2016, according to Trend News Agency, Daily Times, Tehran Times, and Mehr News

Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif

Deeply concerned about the crisis in Turkey. Stability, democracy & safety of Turkish people are paramount. Unity & prudence are imperative.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) July 15, 2016

Turkish people's brave defense of democracy & their elected government proves that coups have no place in our region and are doomed to fail.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) July 16, 2016

“We were the first country that explicitly declared our position regarding Turkey, while other countries either kept mum or …were vague in their stance, if they adopted any, and failed to voice their support for democracy.”

—July 17, 2016, addressing parliament, according to Iranian media

Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani

“[This was] victory of the nation’s will, national sovereignty and democracy over a desperate and doomed measure”

“[This was] victory of the nation’s will, national sovereignty and democracy over a desperate and doomed measure”

“Events over past few hours showed very well that the nations’ vote, will and demand are decisive.”

“[Iranian parliament] condemns the military move against democratically-elected institutions, particularly the attack on Turkey’s parliament as the symbol of democracy and the nation’s will and demand.”

“I would like to congratulate your Excellency, the Turkish people and members of parliament on the victory of the people’s will, national sovereignty and democracy over desperate and ‘doomed to failure actions’ against your country’s institutions,”

—July 16, 2016, in a statement to his Turkish counterpart, Ismail Kahraman, according to Press TV and Tehran Times

Ali Akbar Velayati (advisor to the supreme leader)

“The Islamic Republic of Iran is a state governed by religious democracy, i.e. a government based on popular vote within the framework of Islamic values and is naturally against any illegal move and act of bullying to change popular governments.”

“If a few military personnel seek to crush underfoot the vote of the people under the influence of whatever factor or factors and overthrow the popular government of Erdogan, the Islamic Republic of Iran will naturally and according to the principles it believes in oppose this coup d’état or any other coups.”

“We hope that a day would come when the Turkish administration would also respect the opinion and vote of the Syrian people and leave it to the Syrian people to determine their government.”

“Regardless of some political differences, many commonalities bring Iran and Turkey together. These two countries with a common history, religion and border have existed side by side for centuries.”

“We disagree with Turkey on some issues, like Syria. We are hopeful that the Turkish government respects the Syrian people's opinion and votes and lets the Syrian nation choose their government.”

—July 16, 2016, according to Tasnim News Agency via Reuters and Iran Front Page

Supreme National Security Council Secretary Ali Shamkhani

“We are following the events in Turkey warily and carefully,”

“We are following the events in Turkey warily and carefully,”

“All of the land and air borders with Turkey are under full control, and comprehensive surveillance is underway in the areas.”

“We support Turkey's legal government and oppose any type of coup - either initiated domestically or supported by foreigners.”

—July 16, 2016, according to Iran Front Page and Reuters media

Bahram Qassemi, Iran Foreign Ministry Spokesman

“We are deeply concerned about stability, security, unity, democracy and rule of law in Turkey.”

“A stable, secure and democratic Turkey is a priority for the Islamic Republic of Iran,”

—July 16, 2016, according to Press TV and Tasnim News Agency

Hossein Sheikholeslam (advisor to Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani)

“The elimination of terrorists in Syria is a big strategic loss for the Zionist regime [Israel]; therefore, I don’t see it unlikely that what happened in Turkey was the result of efforts made by Americans, Saudis, Egyptian intelligence, and Zionists.”

“It is no secret to anyone that the masterminds of the coup also had close relations with the Zionist regime.”

“The threat resembles the approach adopted by Bandar bin Sultan, the former Saudi Arabian ambassador to the US, against the Russian President Vladimir Putin. Bandar had implicitly threatened to carry out terrorist attacks in Russia.”

—July 18, 2016, according to media

Member of Parliament Ali Asghar Yousefnejad

“Coups are not acceptable in any government. Governments should be formed based on people’s votes.”

—July 17, 2016, according to ICANA via Iran Front Page

Member of Parliament Akbar Ranjbarzadeh

“Although Turkey has an instable structure because of its government’s incapability, the coup should not have taken place, killing Turkish people and causing insecurity,”

“It is believed that other countries have had roles in the coup. Among these countries, Saudi Arabia is the most possible option, and al Saud’s interference in Turkish coup is not unbelievable, because such a coup has definitely had foreign backers.”

“As Saudis caused disorders in the Middle Eastern countries including Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, and many more, and now they are trying to extend it to Turkey,”

—July 17, 2016, according to ICANA via Iran Front Page

Member of Parliament Jafar Zade

“During the coup in Turkey, Foreign Minister Zarif, [Qods Force] General [Qassem] Soleimani and Shamkhani were in contact with each other, monitoring the events.”

“Zarif said ‘the possibility of Saudi's interference in Turkey coup is high.’”

“Erdogan didn’t come to Iran during the coup.”

—July 17, 2016, according to Entekhab journalist Rohollah Faghihi

Member of Parliament Ruhollah Beigi

“The coup in Turkey might have been orchestrated by Erdogan himself.”

“I'm suspicious of the coup in Turkey.”

—July 17, 2016, according to Entekhab journalist Rohollah Faghihi