Katayoun Kishi

Iran is scheduled to hold elections on February 26 — for parliament and the Assembly of Experts — that could shift the political balance of power. Hardliners have dominated parliament for more than a decade. But reformists, centrists and moderate conservatives are jockeying for a greater share of the 290 seats in the Majles. Members are popularly elected to four-year terms, and their duties include drafting laws, approving international treaties, and supervising the annual budget.

The simultaneous election for the Assembly of Experts, which selects and oversees the supreme leader, will be just as important. The body of Islamic jurists is somewhat comparable to the Catholic College of Cardinals. It sits for eight years and may select the successor to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is now 76. The next leader is also likely to be one of those 88 jurists– increased from 86 jurists in previous years.

An unprecedented number of potential candidates have registered for the parliamentary and Assembly of Experts elections – 12,123 and 801, respectively. This number far surpasses previous years and represents a 62 percent increase in the number of Assembly candidates and more than double the amount of parliamentary candidates since the last election. A greater number of women have also registered to run than in previous years. Women comprise 12 percent of registered parliamentary candidates, an increase of four percentage points since the last election. Sixteen women have also registered their candidacies for the Assembly of Experts, marking the first time in history that women have vied for these seats. In January, the Guardian Council invited 537 of those who registered to take the qualification tests required for candidacy – among them were 10 women candidates.

Hundreds of women across Iran register to run for 10th Parliament in the upcoming election. Members serve 4 years. pic.twitter.com/t1UdSDc24K

— Negar نگار (@NegarMortazavi) December 23, 2015Since the nuclear deal was concluded on July 14, both reformers and hardliners have said the election will also be a referendum on the revolution’s future direction. The deal has been a boon for centrist President Hassan Rouhani, whose overall approval rating hit 89 percent in August, and could boost the prospects of his supporters at the polls. Tensions over the nuclear deal between his supporters and hardliners who opposed the deal were partly related to the upcoming elections. In September, former President Hashemi Rafsanjani predicted that the voters will “teach hardliners a lesson.” Hardliners echoed the same sentiment. “If there’s a nuclear deal, twenty to twenty-five per cent of people’s votes will go to candidates who favor the Rouhani government,” Hamid Reza Taraghi, leader of the hardline Islamic Coalition Party, told The New Yorker in mid-2015.

Even some conservative clerics forecast a political shift. In September, Mohsen Gharavian, a conservative in the holy city of Qom, told Abrar News, “The government is also making an effort to improve people’s lives through economic relationships and diplomacy. I think the people will show greater support for this moderate line.”

Timeline: Election Deadlines

Dec. 17-23, 2015: Candidate registration period for Assembly of Experts election

Dec. 19-25, 2015: Candidate registration period for parliamentary election

Jan. 26, 2016: Last day for Guardian Council to inform Assembly of Experts candidates of their qualification or disqualification

Jan. 30, 2016: Appeals from disqualified Assembly of Experts candidates are due to the Guardian Council

Jan. 31-Feb. 9, 2016: Guardian Council reviews Assembly of Experts complaints

Feb. 5, 2016: Guardian Council informs parliamentary candidates of their qualification or disqualification

Feb. 6-8, 2016: Disqualified parliamentary candidates may file complaints to the Guardian Council

Feb. 9-15, 2016: Guardian Council reviews parliamentary complaints

Feb. 10: Guardian Council sends final list of Assembly of Experts candidates to officials

Feb. 11-24, 2016: Campaign period for Assembly of Experts candidates

Feb. 16, 2016: Guardian Council submits finalized list of approved parliamentary candidates to Interior Ministry

Feb. 18-24, 2016: Campaign period for parliament candidates

Feb. 26, 2016: Election Day

Candidates and Parties

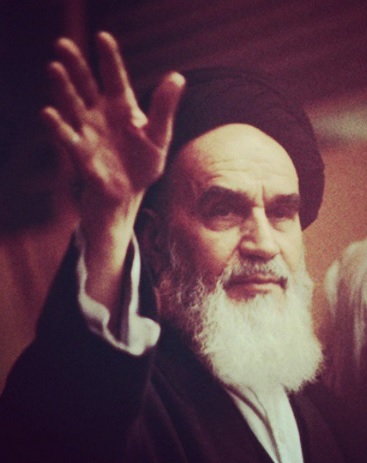

Iran had only one party after the 1979 Revolution, but it quickly imploded under the pressure of factions that had diverse visions for the future. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini once ordered Iran’s squabbling politicians to stop “biting one another like scorpions.” By 2016, these diverse visions had developed into a complex political spectrum that featured dozens of disparate parties. It included rivalries even among hardliners and differences among reformers– with many other categories in between.

Iran had only one party after the 1979 Revolution, but it quickly imploded under the pressure of factions that had diverse visions for the future. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini once ordered Iran’s squabbling politicians to stop “biting one another like scorpions.” By 2016, these diverse visions had developed into a complex political spectrum that featured dozens of disparate parties. It included rivalries even among hardliners and differences among reformers– with many other categories in between.The Islamic Republican Party (IRP) was the first post-revolution political party in Iran. It became the only legal party in 1981, but dissolved in 1987 due to internal ideological clashes. After the dissolution of the IRP, Iran shifted from a single-party state to one that contained a multitude of parties from across the political spectrum. These parties have various views on social and political liberties and the democratic versus Islamic emphasis of the state, but none challenge the veliyat-e faqih, the governance of the jurist and the basis of Islamic government. Various factions and coalitions dominate the political scene since individual political parties typically have weak internal structures and vague policy platforms.

Generally, those on the right side of the political spectrum emphasize Islamic social values and support a free market economy – a likely result of their connections to the bazaar merchants. Conservative groups like the Society of Combatant Clergy include many members of the clergy and are influential in institutions like the Guardian Council and Assembly of Experts. Other conservative parties like the Isagaran, founded in part by former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, are also socially conservative but advocate for centralization of the economy – evidence of the variety of views that exist among right-wing parties. In parliament, the United Front of Principlists, the Islamic Revolution Stability Front, and Rahrovan-e Velayat (Followers of the Leader) factions serve as the main wings of the conservative and hardline groups.

Left-wing groups generally support the more populist aspects of the revolution. They tend to emphasize the democratic features of the revolution and advocate for state-centered economics. In the 1990s, reformist groups like the now-banned Islamic Iran Participation Front joined together to form the Second Khordad Front, a coalition of 18 reformist organizations. These parties supported greater political liberalization and normalization of Iran’s foreign policy while still supporting the absolute mandate of the supreme leader.

There are some groups that fall in the center of the spectrum as well, working with both conservative and reformist parties. Notably, the Executives of Construction, a centrist party, deviated from traditional conservatives by pushing for more social liberties and market economics. By doing so, it became the foundation for the “Modern Right” faction of Iranian politics. Since Rouhani’s election, a group of nearly 70 MP’s announced a split from the traditional conservative Rahrovan-e Velayat (Followers of the Leader) faction and formed the Seday-e Mellat (Voice of the Nation) faction of pro-Rouhani members.

There are some groups that fall in the center of the spectrum as well, working with both conservative and reformist parties. Notably, the Executives of Construction, a centrist party, deviated from traditional conservatives by pushing for more social liberties and market economics. By doing so, it became the foundation for the “Modern Right” faction of Iranian politics. Since Rouhani’s election, a group of nearly 70 MP’s announced a split from the traditional conservative Rahrovan-e Velayat (Followers of the Leader) faction and formed the Seday-e Mellat (Voice of the Nation) faction of pro-Rouhani members.Notable political parties and coalitions from Iran’s electoral history include:

- Islamic Republican Party (IRP): The IRP was founded in 1979, by five prominent clerics close to Khomeini, including Rafsanjani and Khamenei. The party supported the anti-Western sentiments of the revolution, Islamic principles, and strong state control of the economy. It had the most members elected to the first parliament. In 1981, Iran banned all political parties other than the IRP. Despite dominating the second parliamentary elections, divisions grew within the party between conservatives who backed then-President Khamenei and leftists who backed Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi. Khomeini dissolved the party in 1987.

- Society of Combatant Clergy: Supporters of Khomeini established this clerical organization in 1977, and the group wielded significant influence in many of Iran’s post-revolution institutions. In 1987, there were internal divisions based on several issues including economic policies and the supreme leader’s role. The organization split when the leaders of its conservative and leftist factions could not resolve these disagreements. The Association of Combatant Clerics became the leftist, populist offshoot of the Society. It won the majority of seats in the 1988 third parliamentary elections. The conservative Society of Combatant Clergy regained the majority in the 1992 fourth parliamentary elections, however, partly due to aggressive vetting of reformist candidates by the Guardian Council. It also fared well in the 1996 fifth parliamentary elections and remains influential in the Assembly of Experts and Guardian Council.

- Second Khordad Front: The Second Khordad Front was formed in 1997, named after the date of Mohammad Khatami’s landslide election to the presidency. It is a coalition of 18 reformist organizations and political parties, including the Association of Combatant Clerics and the Islamic Iran Participation Front. Candidates affiliated with the Second Khordad Front won 65 percent of the seats in the 2000 sixth parliamentary elections. In the 2004 parliamentary elections, the Guardian Council disqualified many of the Front’s members. The group boycotted the elections and lost its majority in Parliament.

- Islamic Iran Participation Front (IIPF): Founded in 1998, the IIPF was one of the largest reformist parties in Iran. It advocated for more liberal interpretations of Islam, a free market economy, and stronger political liberties. The IIPF constituted the largest segment of Parliament (150 seats out of 290) after the reformist landslide victory in the 2000 parliamentary elections. It lost many of those seats, however, when it boycotted the 2004 elections. The IIPF was banned in 2010 after it joined the candidate it endorsed, Mir Hossein Mousavi, in protesting the reelection of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

- Executives of Construction: Rafsanjani created the Executives of Construction party with 16 of his cabinet members before the 1996 fifth parliamentary elections. The centrist party was very influential in the fifth parliament, but lost many of its seats due to Guardian Council disqualifications in 2004. It pushed for greater social liberties and free market economics, and supported Mir Hossein Mousavi in the 2009 presidential election.

- Association of the Devotees of the Islamic Revolution (Isagaran): The Isagaran was founded in 2001 as the right-wing offshoot of the Organization of the Mojahedin of the Islamic Republic after it was dissolved in 1986. Isagaran backed Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf in the 2005 presidential election, even though Ahmadinejad, one of the founding members of the group, was also running. It later supported Ahmadinejad in the 2009 presidential election. Politically, Isagaran supports the Absolute Guardianship of the Jurist (giving absolute power to the supreme leader) and centralization of economic decisions. It is socially conservative.

- United Front of Principalists: The United Front of Principalists is a coalition of conservative parties formed in 2008. It is supported by the supreme leader, the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), bazaar merchants, and influential clerics. It was formed in direct opposition to Ahmadinejad’s core group of supporters, dubbed “the deviant current.” It was the largest group of conservatives in the 2008 election, and is currently led by Ali Larijani, the Speaker of parliament.

Since the last election, both reformers and conservatives have founded new parties.

In March 2015, the Union of Islamic Iran People Party reformist party received its permit for political activity. The party has 30 executive members, many of whom were members of the Islamic Iran Participation Front (IIPF) banned in 2010. Conservatives claimed that the new party was merely a front for the IIPF.

Nedaye Iranian, another reformist party, formed in December 2014. The party has expressed support for the release of opposition leaders, notably former Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi and former Speaker of parliament Mehdi Karroubi. Nedaye Iranian has 2,300 members and is headed by Sadegh Kharrazi, a former ambassador to Paris.

In September, Tehran Mayor Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf announced the creation of the conservative Iranian-Islamic Freedom Party. Though it is headed by Issa Kakoui, he is widely believed to be only a figurehead. Qalibaf said he hopes the new party will win 30 seats.

In September, Tehran Mayor Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf announced the creation of the conservative Iranian-Islamic Freedom Party. Though it is headed by Issa Kakoui, he is widely believed to be only a figurehead. Qalibaf said he hopes the new party will win 30 seats.Qalibaf was a candidate in the 2013 presidential election and finished in (a distant) second place behind Rouhani. At the time, he was backed by a public endorsement from 120 members of the Majles, which gave him the support of over 40 percent of the conservative-dominated parliament.

Potential Impact

Until Rouhani’s 2013 win, hardliners and conservatives controlled all three branches of government, as well as the military, intelligence agencies and a wide range of Islamic institutions. The loss of control over the Majles would be a major political setback, leaving the judiciary as hardliners and conservatives’ strongest asset. Yet they could still wield power through their dominance over other behind-the-scenes agencies. The supreme leader would also still hold ultimate authority.

A political shift in parliament could, in turn, shift its agenda and priorities. After the nuclear deal, parliament turned its attention to impending improvements in the economy, welcoming new trade deals, and reducing unemployment. Iran has begun to rebuild trade relationships with European and Asian countries, and in December announced its intentions to join the World Trade Organization. Sanctions relief could begin as early as January, which could create an “economic windfall”, a sudden influx of income, for Iran according to The World Bank. Iranians hope that their country will reap economic, social, and political benefits from the nuclear deal, and this optimism could translate into votes for centrists and reformists in the elections.

A reformist-dominated legislature could also assist Rouhani in easing social and press restrictions in the future. In the months leading to the election, Rouhani made several comments regarding journalist arrests and press freedoms. In November, he spoke against the closing of several newspapers and accused the intelligence agencies of making decisions about press freedom that should be made by the judiciary. He also campaigned on promises of more social freedoms, and the signing of the nuclear deal has already led to more Iranians reclaiming some of those freedoms. Iranians are wearing more brightly colored clothing, play music in the streets, organize stand-up comedy events, and have formed non-governmental organizations that protest (successfully) against animal abuse and for environmental issues.

1st Islamic women’s fashion show in Iran http://t.co/DQjjw4QTin #Realiran pic.twitter.com/Z1VEUzbxj0

— Real Iran (@real_iran) September 9, 2015Assembly of Experts

In September, Khamenei told the Revolutionary Guards that he may not be around in a decade.

This election could be among the most significant in Iran's history since the next supreme leader is likely to emerge from the new Assembly. The next veliyat-e faqih could have significant influence on both the limits and openings of political, economic and social life. In December, Rafsanjani said the Assembly picked a group to draft a list of potential successors. Possible contenders could include Rafsanjani, former judiciary chief Grand Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, Assembly of Experts chairman Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi, judiciary chief Ayatollah Sadegh Larijani, and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s grandson Hassan Khomeini.

This election could be among the most significant in Iran's history since the next supreme leader is likely to emerge from the new Assembly. The next veliyat-e faqih could have significant influence on both the limits and openings of political, economic and social life. In December, Rafsanjani said the Assembly picked a group to draft a list of potential successors. Possible contenders could include Rafsanjani, former judiciary chief Grand Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, Assembly of Experts chairman Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi, judiciary chief Ayatollah Sadegh Larijani, and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s grandson Hassan Khomeini.Some 200 potential candidates for the Assembly took the first of a series of exams required to qualify for candidacy in early September, according to the Tehran Times. In January, the Guardian Council announced a new requirement that all candidates, excluding incumbents, would have to complete a written exam.

Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, the chairman of the Guardian Council, warned against politicization of the Assembly, but there was still widespread speculation about which major political players might run.

In August, former President Rafsanjani, who is widely believed to covet the position of supreme leader, announced that he would run. He was elected head of the Assembly in 2007 but opted not to run again in 2011, under pressure from hardliners and conservatives to withdraw. He registered for the election in December.

The media speculated about the candidacy of Seyyed Hassan Khomeini, grandson of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini. Ayatollah Mousavi Bojnurdi, a former member of the Supreme Judicial Council, predicted, “If he announces his candidacy for the Assembly of Experts, he will of course have the support of the reformists.” Khomeini did register to run in the Assembly election, and all eyes now turn to the Guardian Council to see if it will disqualify him. Khomeini registered to run as an independent, and his family name and status would make his disqualification controversial. Some have wondered, however, whether Khomeini has enough religious expertise to be qualified for a seat on the Assembly.

Hassan Khomeini, grandson of ex Leader, @ interior ministry HQ now, filling out form to run for assembly of experts pic.twitter.com/PrxYZUj7aQ

— Alborz Habibi (@AlborzHabibi) December 18, 2015Some speculated that President Rouhani would run for a seat in the Assembly, and in December he announced that he had indeed registered for the election. Rouhani had been elected to the Assembly twice before in 1998 and 2006, and he is not the first president to have run for an Assembly seat while holding office – Rafsanjani did so as well. His bid has the potential to increase the attention and politicization of the election.

Guardian Council Role

All candidates for both parliament and the Assembly of Experts must be vetted by the Guardian Council, 12 Islamic jurists appointed by the supreme leader. It can disqualify candidates without explanation, although its members have insisted that disqualifications are based only on the law. Its aggressive vetting of reformist candidates has contributed to the domination of hardliners and conservatives in parliament for almost a decade. Following candidate registration for the two upcoming elections, the Council’s spokesperson announced that it would take into account the candidates’ comments and behavior during the 2009 Green Movement protests when making its decisions about disqualification. This could prove detrimental for reformist candidates.

All candidates for both parliament and the Assembly of Experts must be vetted by the Guardian Council, 12 Islamic jurists appointed by the supreme leader. It can disqualify candidates without explanation, although its members have insisted that disqualifications are based only on the law. Its aggressive vetting of reformist candidates has contributed to the domination of hardliners and conservatives in parliament for almost a decade. Following candidate registration for the two upcoming elections, the Council’s spokesperson announced that it would take into account the candidates’ comments and behavior during the 2009 Green Movement protests when making its decisions about disqualification. This could prove detrimental for reformist candidates.Several key reformist parties boycotted the 2012 parliamentary elections to protest excessive vetting of candidates. (Voter apathy from the disputed 2009 presidential elections also reduced voter turnout in key areas like Tehran.) The lower reformist turnout resulted in a victory for the moderate conservative coalition, the United Principlist Front, and paved the way for hardliners to build a minority bloc that challenged President Rouhani’s policies.

In August, Rouhani criticized past vetting and pledged that the next elections would be held “in a free and healthy manner.” Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani also warned against the disqualification of candidates.

Under Article 28 of the Elections Act of Islamic Consultative Assembly, parliamentary candidates must meet the following qualifications:

1. Believing and practically binding to the Islamic Republic of Iran

2. Iranian Nationality

3. Binding to the Constitution

4. Holding at least a Master’s Degree or its equivalent (excluding incumbents)

5. Having no bad reputation in the elections station

6. Physical Health at the extent of being able to see, hear and speak

7. At least aged 30 and at most aged 75

Katayoun Kishi is a research assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

For more information about the role of parliament, click here.

For more information on the Assembly of Experts, click here.

Photo credits: Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf by Seyed Shahabbodin, Vajedi (http://akkasemosalman.ir/g-chehreha/siyasi/) [CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Assembly of Experts via Assembly of Experts website; Ahmad Jannati via Guardian Council website