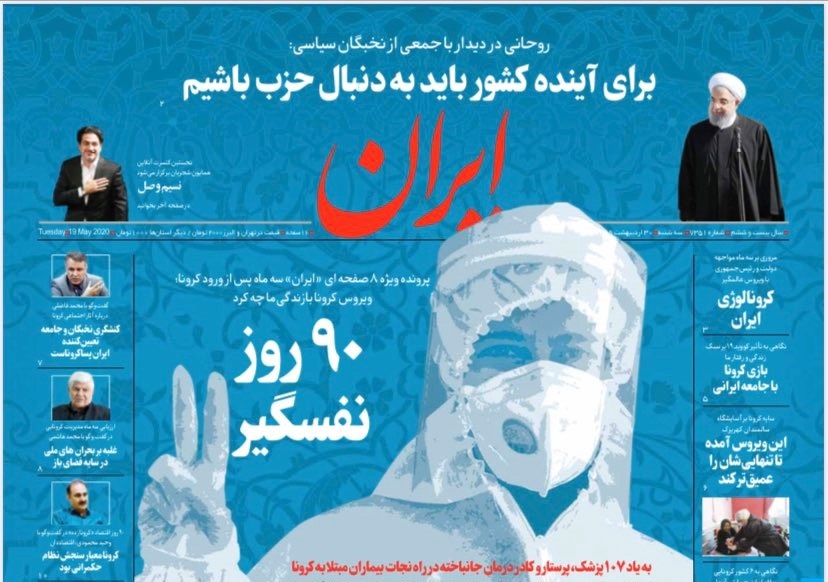

Iran’s doctors and nurses have made heavy sacrifices in the fight against COVID-19. In the first three months of the pandemic, more than 100 healthcare workers died and some 10,000 had been infected. The death toll could be much higher, since statistics were still being collected from across the country, Hossein Kermanpour, director for public relations for the healthcare system, said on May 18. On May 19, the government daily printed the names of 107 healthcare workers who died from COVID-19 as part of an eight-page spread.

Deaths from COVID-19 have been underreported because of the way that Iran counts the cases, according to Kamiar Alaei, an Iranian health-policy expert and co-president of the Institute for International Health and Education in Albany, New York. Many people – including some healthcare workers – were misdiagnosed due to low sensitivity of tests or diagnosed clinically or via CT scans instead of coronavirus test kits, so they were not included in official tallies. “The causes listed for deaths are general terms like respiratory syndrome,” Alaei said. He added that many of the tests imported from China had sensitivity rates as low as 30 percent to 50 percent, so the virus could have gone undetected in some cases.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei recognized medical staff who died as martyrs, the same distinction given to fallen soldiers. “The sacrifices made were so dazzling that even foreigners felt obliged to admire them,” he said on March 20. He earlier said that physicians, nurses and were “engaged in a jihad in the way of God.”

But the central government came under intense criticism for its slow response to the pandemic and lack of transparency. Medical professionals, lawmakers, provincial and local officials, and journalists raised the alarm inside Iran. Healthcare experts abroad also said that the regime’s decisions lead to unnecessary deaths among medical workers and the general public. Iran’s healthcare system – one of the best in the Middle East – was caught off-guard because of political decisions.

Government Denial of the Threat

In late December and January, authorities ignored warnings from doctors who were treating patients with lung infections and flu-like symptoms that matched descriptions out of China of COVID-19. Hospital officials reportedly ordered doctors not to release infection or death rates and not to wear masks or protective equipment. “The aim was to prevent fear in the society, even if it meant high casualties among the medical staff,” a doctor from the city of Gorgan told The New Yorker.

For weeks, the government withheld information from the public about the outbreak for two reasons, according to a senior official. The first reason was to ensure a decent turnout in parliamentary elections scheduled for February 21. The regime, which cites turnout as a reflection of public support, reported the first cases – both deaths – on February 19 but downplayed the risk of infection.

The second reason was to avoid upsetting relations with China – an important ally and Iran’s biggest trade partner – where the virus originated. “Initially, officials were unwilling to restrict Iranian exports to China, impose travel restrictions, or implement the necessary quarantine measures for fear of harming the economy,” according to Amir Afkhami, a medical doctor and historian at the George Washington University.

The government’s cavalier attitude toward the virus misled a proportion of healthcare workers, many of whom did not take it seriously at first, according to Alaei. “The health ministry was initially slow to release updated guidance, so doctors and nurses were not prepared to treat COVID-19 patients or protect themselves from infection,” he said.

President Hassan Rouhani at a meeting of the National Task Force for Fighting Coronavirus

On February 25, President Hassan Rouhani assured the public that the health ministry would issue guidelines and that the situation was under control. He accused the United States of using propaganda to sow fear to shut down Iran’s economy.

Shortage of Personal Protective Equipment

By early March, the virus had spread to all 31 provinces and severely taxed the healthcare system. But medical staff still lacked enough personal protective equipment (PPE). Some healthcare workers reportedly washed their gowns or masks or tried sterilizing them in ovens for reuse. Some covered themselves with plastic grocery bags. Medical staff in several cities, including Tehran, told France24 that they only had adequate equipment when state-controlled TV crews came to film at their hospitals. Some workers used their own money to buy PPE.

Gilan, a northern province along the Caspian Sea, was hit especially hard. “We are in desperate need of N95 masks right now, and we ran out of them yesterday,” the head of the Gilan Nursing Organization, Mohammad Delsuz, told Shargh newspaper on March 9. He said that nurses resorted to using homemade masks. Doctors and nurses in Langeroud, also in Gilan, took to social media to ask the public to donate equipment. “It’s urgent! If the situation continues like this, no one among our medical staff will be left to take care of the patients. Because of the lack of protective equipment all of our medical staff will be infected.”

Another hospital turned to the black market to buy N95 respirators due to limited access to effective face masks. N95 respirators can filter out bacteria and viruses, but many purchased on the black market did not have adequate filters to protect workers. Staff got infected while using the masks, according to Alaei.

Volunteers set up some 185 sewing workshops across Iran to supply medical staff with protective gowns and simple masks.

1600+ volunteers 🧕🏽

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) May 15, 2020

185 sewing workshops🏠🏫

Since February, these generous people from the underprivileged areas of Tehran, #Iran 🇮🇷 produced over a million masks 😷 & 57,800 gowns for health care workers.

We can beat #COVID19 when we work together! https://t.co/XCbnNfs1ID pic.twitter.com/wmoMMM5aPA

U.S. Sanctions Blamed for Shortages

Iranian officials blamed U.S. sanctions for hindering its ability to import medical supplies during the crisis. “The world can no longer be silent as US #EconomicTerrorism is supplanted by its #MedicalTerrorism,” Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif tweeted on March 7. Five days later, he tweeted a list of supplies and equipment that the health ministry needed, including 160 million three-layer masks, 12 million N95 masks, 100 million gloves, and other medical goods.

URGENT

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) March 12, 2020

Iranian care personnel are courageously battling #COVID19 on frontlines

Their efforts are stymied by vast shortages caused by restrictions on our people's access to medicine/equipment

Most urgent needs are outlined below

Viruses don't discriminate. Nor should humankind pic.twitter.com/GpXCbsh001

In February 2020, the United States offered aid to Iran, but President Hassan Rouhani and Supreme Leader Khamenei rejected it. “You might give us a medicine that would spread the disease even more or make it last longer,” Khamenei said on March 22.

Months before the outbreak, Human Rights Watch had warned that sanctions were contributing to shortages of medicine and supplies despite exemptions for humanitarian goods. “Broad U.S. sanctions against Iranian banks, coupled with aggressive rhetoric from U.S. officials, have drastically constrained Iran’s ability to finance such humanitarian imports,” according to a report published in October 2019.

Aid to China First

Iran had the domestic capacity to produce PPE, but demand increased exponentially –when stocks were already low. China had purchased bulk orders of masks from Iran in January and February. Tehran had also donated three million face masks at the very outset of the crisis to China, according to Suzanne Maloney, director of the Foreign Policy Program at the Brookings Institution. “Chinese companies were purchasing masks and helping to create a shortage in the domestic market. There was as well the accusation of hoarding, of the distrust and sense of secrecy that was part of the early response to the crisis. It fueled this broader sense that this is not a government that is capable of managing a crisis of this extent in a way that really reflects the Iranian national interest.”

Sacrifice Recognized

Health workers worked long hours and stayed at hospitals for days and weeks at a time to protect their families from infection. In March, a nurse in small town in the south-west told the Financial Times that he worked up to 19 hours a day and slept in a house with five colleagues. A nurse who had planned to get married in February delayed her wedding until May.

Nasim Shoustari, a nurse in Tehran, was forced to delay her wedding as she worked in a COVID-19 ward.

— Esfandyar Batmanghelidj (@yarbatman) May 10, 2020

Now she is finally getting married.

Photojournalist Hassan Shirvani, who photographed Nasim at Firoozabadi Hospital in March, was there to capture the joyful preparations. pic.twitter.com/Vf7REANQlS

On March 17, President Rouhani unveiled a stamp commemorating the medical professionals fighting Iran's coronavirus outbreak. The stamp was inscribed with the words “National Heroes.” Rouhani compared medical workers to soldiers in a speech on National Army Day. “The enemy now is hidden and doctors and nurses are at the frontlines of the battlefield,” he said on April 17. The families of martyrs, usually members of the armed forces or security services, receive state benefits, such as payments, subsidized housing and education. But it was unclear if medical staff would receive those benefits.

Iran’s #coronavirus #stamp salutes #medical workers. #Iran has unveiled a postage stamp honoring medical professionals as front-line fighters of the #COVID19 outbreak in the country https://t.co/wC57pPSNnA #HealthForAll @WHO #WHO @iranpostCO @M_Sarkheil @Mm_Bahrami #philately pic.twitter.com/T5MzeHnjn1

— UniversalPostalUnion (@UPU_UN) March 19, 2020

Coping with Trauma

Many medical staffers were reportedly traumatized from treating COVID-19 patients and witnessing their deaths. The shortage of ventilators and hospital beds forced doctors and nurses to make difficult decisions about which patients to treat. The armed forces created field hospitals to expand the healthcare system’s capacity. In March, the Army set up 2,000 beds in an exhibition center in the capital. In April, the Iran Mall – one of the world’s largest – was converted into a 3,000 bed hospital for COVID-19 patients as Tehran’s hospitals filled up.

As morale boosters, medical staff posted videos of themselves dancing as part of a “dance challenge” issued on social media to teams across Iran treating coronavirus patients.

Dance video of another health worker fighting #Coronavirus at a hospital in #Iran. Fight the virus with the Iranian spirit. (thread) pic.twitter.com/n5wJSAIAnf

— Negar Mortazavi نگار مرتضوی (@NegarMortazavi) March 4, 2020

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of The Iran Primer at the U.S. Institute of Peace.