For Iran, 2021 was a year of major transitions in both politics and foreign policy. President Hassan Rouhani, a centrist, finished his second term with much of his agenda unfulfilled and the future of his signature policy project, the 2015 nuclear deal, in doubt. Ebrahim Raisi’s victory in the June presidential election solidified hardline control over all three branches of government – the executive branch, the judiciary and parliament. But Raisi faced a litany of challenges, including a fifth wave of COVID-19 infections, protests over water shortages, and rising consumer prices. The headlines of 2021 included:

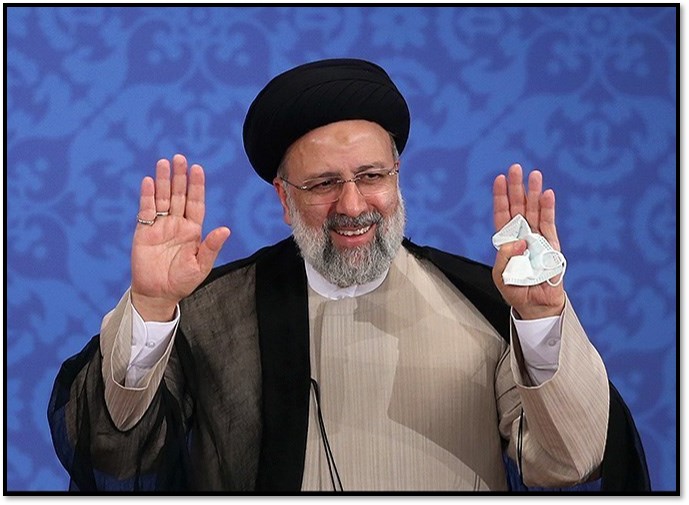

- In politics, Ebrahim Raisi, a hardliner, won the June presidential election with 62 percent of the vote. But he lacked a popular mandate because most Iranians didn’t vote. The turnout was just 48.8 percent, the lowest turnout in the history of the Islamic Republic.

- In foreign policy, Raisi accelerated Iran’s pivot to the East by expanding ties with China and solidifying ties with Russia. He also prioritized improving relations with its Arab and South and Central Asian neighbors.

- On nuclear diplomacy, Iran’s new negotiating team backtracked on compromises made by its predecessors with the world’s major powers. It specifically demanded more concessions from the United States on sanctions relief. Iran also breached several limits set by the 2015 nuclear deal. For the first time, it enriched uranium to 60 percent. Uranium enriched to 90 percent or above is generally considered weapons grade. Iran also used increasingly advanced centrifuges to enrich uranium. By late 2021, its breakout time – the time needed to produce enough fuel for one nuclear weapon – was down to approximately one month. But the nuclear program also faced setbacks. In April, an explosion at the Natanz facility hit the power supply for centrifuges and caused damage that could take up many months to fully repair.

- On national security, Iran developed and tested combat drones and both ballistic and cruise missiles. It allegedly attacked three Israeli-owned cargo ships and two others with connections to Israelis using mines, missiles and drones. Iranian fast-attack boats also harassed U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf.

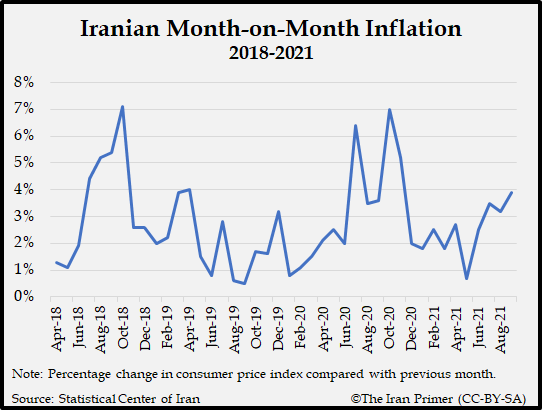

- On the economy, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by 2.5 percent despite pressure from hundreds of U.S. sanctions. Iran continued to export a limited amount of oil, mostly to China. But inflation remained high, hovering between 35 and 50 percent from January through November.

- On public health, Iran faced the two deadliest waves of COVID-19 infections since the pandemic began in February 2020. The vaccine rollout under Rouhani was slow. But Raisi, who took office in August, prioritized importing doses and boosting domestic production. By mid-December, 57.8 percent of the population was fully vaccinated, nearly the same percentage as in the United States (60.5 percent).

- On the environment, Iran faced a serious drought. Protests broke out in southwestern Khuzestan province on July 15 over water shortages and continued for weeks. Security forces reportedly killed at least eight protestors and bystanders in the crackdown. In November, farmers in historic Isfahan staged a sit-in on the dry bed of the Zayanderoud River for more than two weeks before security forces broke up their camp.

In Politics

Hardliners gained more power through elections in 2021. In polls, the majority of Iranians disapproved of President Rouhani during his final months in office. In February, a majority of Iranians – 62 percent – held an unfavorable view of Rouhani, while 61 percent said that the economy had worsened under his administration, according to a poll conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and IranPoll. Nearly two-thirds of Iranians said that they preferred a critic of Rouhani as the next president.

In May, Iran’s presidential campaign kicked off. Ebrahim Raisi, a hardliner who failed to unseat Rouhani in the 2017 election, was the clear frontrunner. As judicial chief and a former candidate, he had national name recognition. Raisi also did not face stiff competition. The Guardian Council, a 12-man panel of jurists, had barred several prominent politicians from the race. Only seven out of nearly 600 candidates who registered were approved to run. Five were conservatives, one was a centrist, and one was a reformist. Three candidates dropped out on June 16 – two of whom endorsed Raisi – further narrowing the field.

On June 18, Iran held presidential and municipal elections. Raisi won the four-man race with 62 percent of the votes. But he lacked a broad public mandate. The turnout, just 48.8 percent, was the lowest for a presidential election in the history of the Islamic Republic. Only 28.9 million Iranians – out of the more than 59 million eligible voters – participated. Activists had called for a boycott. Compared to previous elections, the low turnout reflected widespread apathy about both the candidates and the future of the revolution. In 2017, 73.3 percent of eligible voters turned out; in 2013, 72.9 percent participated in the poll.

The election was widely seen as more than a contest for the presidency. It may also have set the stage for the succession after the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has led Iran since 1989. Raisi, a mid-ranking cleric, became a possible successor.

Hardliners also dominated in municipal elections in Tehran. In the 2017 elections, reformists had taken all 21 seats. But in 2021, Many reformists were disqualified. Hardliners won every seat.

In August, Tehran’s new city council elected Alireza Zakani, a prominent conservative lawmaker, as mayor. The position has historically been a springboard for politicians with grander aspirations. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was the mayor of Tehran before he became president in 2005. Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf was the mayor of Tehran before he became the speaker of parliament in 2020. Zakani ran for the presidency in 2021 but dropped out during the campaign to support Raisi. Since becoming mayor, Zakani has been attending Raisi’s weekly cabinet meetings to coordinate with the government.

In Foreign Policy

In 2021, Iran prioritized easing tensions with neighbors and bolstering relations with non-Western powers, namely China and Russia.

On Afghanistan: In August, Iran welcomed the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan while it also scrambled to deal with the sudden influx of thousands of refugees along the 572-mile border. For months, Iran had prepared for the transition by hosting a Taliban delegation in January and intra-Afghan peace talks in July. But Tehran also appeared to be caught off-guard by the Taliban’s sweeping takeover and the rapid collapse of the Afghan army in August.

On Afghanistan: In August, Iran welcomed the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan while it also scrambled to deal with the sudden influx of thousands of refugees along the 572-mile border. For months, Iran had prepared for the transition by hosting a Taliban delegation in January and intra-Afghan peace talks in July. But Tehran also appeared to be caught off-guard by the Taliban’s sweeping takeover and the rapid collapse of the Afghan army in August.

After the Taliban takeover, Iran urged all Afghan factions to resolve their differences through dialogue. It called on the Taliban to hold elections and form an inclusive government. Tehran was specifically focused on instability, refugees, narcotics trafficking, cross-border trade, shared water resources, the Shiite minority, and the threat from Sunni jihadis in ISIS-Khorasan. In October, Iran hosted the foreign ministers of the six countries bordering Afghanistan, and Russia, to discuss shared concerns over the instability.

On China: In March, Iran and China signed a 25-year “strategic partnership” to deepen economic and security ties. The agreement was not published, but a draft released in June 2020 indicated that Beijing would invest billions in exchange for a heavily discounted supply of Iranian oil. Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif responded to public concerns over growing Chinese influence with a fact sheet that emphasized that the agreement was not a treaty and contained no specific commitments on investment or security.

On Saudi Arabia: In April, rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia held direct talks five years after severing diplomatic relations. The talks in Baghdad were mediated by Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al Kadhimi. The discussion focused primarily on Yemen, where Riyadh and Tehran have backed opposing sides since the civil war erupted in 2014. The delegations also reportedly discussed the political and financial crisis in Lebanon, where Iran and Saudi Arabia back opposing political blocs. At least three more rounds of talks, including one after Raisi’s inauguration, were held in 2021.

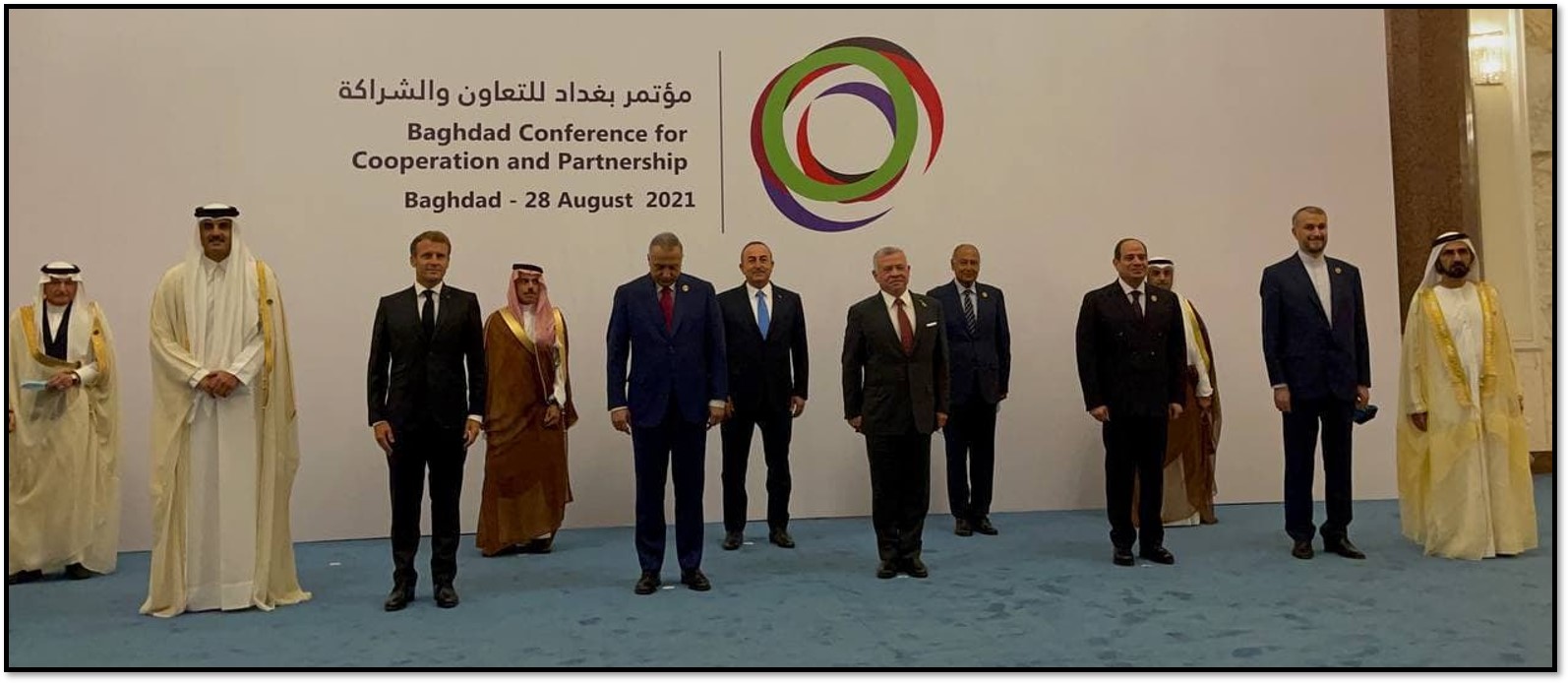

On Regional Countries: The Raisi government’s first major foreign engagement was a regional conference in Iraq in August that also included the presidents, kings or foreign ministers from Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE); French President Emmanuel Macron also participated. The goal was to ease regional tensions, particularly between Iran and the Arab nations.

In September, Iraqi Prime Minister Kadhimi became the first foreign leader to visit Iran since Raisi’s inauguration. In November, Iran expanded its outreach to the Gulf states. Deputy Foreign Minister Ali Bagheri Kani traveled to Kuwait and the UAE. And in December, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan – a senior Emirati national security advisor and brother of Abu Dhabi’s crown prince – made a rare visit to Tehran to improve ties.

On Russia: Raisi expressed eagerness to boost ties, especially on trade, with Russia. After Raisi won the presidential election in June, President Vladimir Putin was the first foreign leader to congratulate him. During a call with Putin in August, Raisi said that Iran was determined to finalize a 20-year cooperation agreement that had been in the works since 2020. Putin welcomed the initiative. He also pledged to “accelerate” the delivery of COVID-19 vaccines to Iran.

On the Nuclear Program and Diplomacy

In 2021, Iran accelerated its nuclear program in accordance with a law passed by Parliament in December 2020, after the assassination of a senior nuclear scientist. The law, which went into effect in February, mandated that the government enrich uranium to 20 percent—up from the 3.67 percent allowed under the 2015 nuclear deal. It also limited the access of international inspectors to some of Iran’s nuclear facilities. President Rouhani complained that implementing the law’s requirements complicated talks on restoring the JCPOA.

Two of Iran’s facilities were sabotaged in 2021. In April, an explosion knocked out an underground power system at the Natanz site. Iran blamed Israel for the attack, which damaged or destroyed thousands of centrifuges. In June, a drone attack reportedly damaged the Karaj facility, which produces parts for centrifuges. Iran again blamed Israel. Despite the setbacks, Iran continued to expand its program.

In the first half of 2021, the Rouhani government engaged in last-ditch diplomacy to restore the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). From April to June 2021, Iran and the major powers – Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States – held six rounds of talks. The logistics were unusual because Iran refused to meet directly with the U.S. delegation. Delegations from Iran and the United States worked out of separate hotels and communicated via European envoys who shuttled messages back and forth.

The goal was to draft a roadmap for the United States to reenter the deal and lift sanctions, and for Iran to roll back breaches on its nuclear program. Diplomacy stalled in June during Iran’s presidential campaign and the political transition as Ebrahim Raisi took office and appointed his cabinet in August.

In continued to advance its nuclear program. By November, Iran had:

- Enriched uranium to 20 percent

- Enriched uranium to 60 percent, the highest level ever acknowledged by Iran

- Produced enriched uranium metal, which could be used to build the core of a nuclear bomb

- Installed and used advanced centrifuges to enrich uranium

The advances helped cut Iran’s breakout time – the time need needed to produce enough fuel for one nuclear weapon – down to as little as three weeks. Many of Iran’s advances were reversible. For example, Iran could stop enriching above 3.67 percent, the limited stipulated in the JCPOA, and ship out excess enriched uranium. But the skills and knowledge gained cannot be unlearned.

At the same time, Iran reduced cooperation with the U.N. nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In February, Iran suspended intrusive verification activities as required by Parliament’s law. It allowed surveillance cameras at key facilities to continue recording and committed to give the data to the IAEA if U.S. sanctions were lifted. For months, Iran prevented the IAEA from reinstalling cameras at the Karaj facility.

In November, the United States warned that the IAEA Board of Governors would have no choice but to convene a special meeting before the end of 2021 – to vote on a resolution to censure Iran – if Tehran did not allow access to Karaj. In December, the IAEA and Iran reached an agreement to allow the agency to replace the cameras. The deal appeared to at least temporarily avert a showdown. But Iran continued to stonewall investigations into its prior activities and uranium traces at four suspect sites.

The world’s major powers and Iran reconvened in Vienna for a seventh round of talks on November 29. But major gaps remained. On December 3, the delegations decided to return to their capitals for consultations. Iran demanded that the United States first lift sanctions imposed by the Trump administration and present guarantees that they will not be reimposed in the future before it would roll back its breaches of the 2015 nuclear deal. The Biden administration has committed to a mutual return to full compliance – at the same time, and without long-term U.S. guarantees – with the deal.

U.S. and European diplomats expressed frustration and concern that Iran backtracked on its earlier proposals. They said that Iran was offering to do less on rolling back its nuclear program while asking for more concessions on sanctions relief. The talks resumed on December 9. But Iran stuck to its position. British, French and German diplomats warned that the JCPOA could “soon become an empty shell,” given Iran’s nuclear advances.

On Military Advances

In 2021, Iran introduced and tested a wide range of weapons, both defensive and offensive.

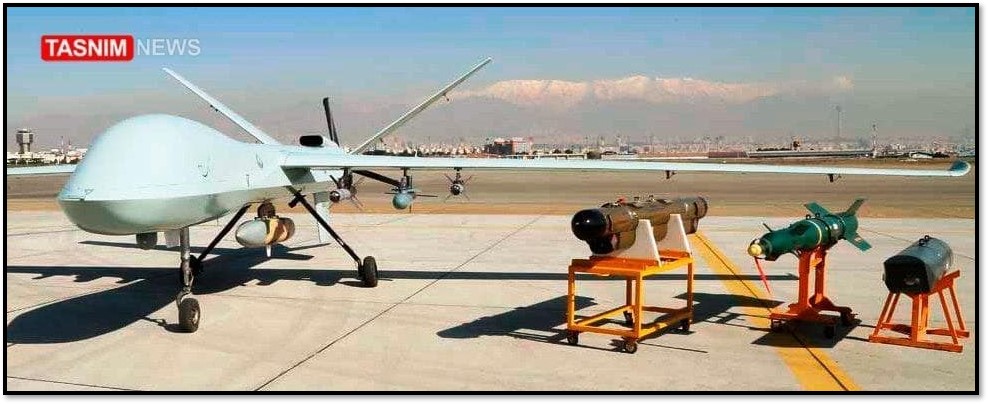

Drones: In February, Iran’s conventional air force introduced the Kaman-22 combat drone, which appeared to be modeled on the U.S.-made MQ-1 Predator. Iranian media reported that it had a range of some 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers). Photos of the drone showed it carrying six bombs. It was reportedly in the final stages of testing.

In May, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) unveiled a new long-range combat drone dubbed the Gaza in honor of the Palestinian resistance against Israel. The IRGC said that it had a range of 1,250 miles (2,000 kilometers) and could carry 13 bombs.

Missiles: In March, state television broadcast footage of an underground “missile city” under the command of the IRGC Navy. The video showed an arsenal of ballistic and cruise missiles in long corridors.

Missile Defense: In August, Iran tested the Mersad 16 air defense missile system. The Mersad 16, which was based on the U.S. MIM-23 Hawk, was designed to shoot down high-speed targets at low altitudes, such as cruise missiles and drones.

In October, Iran tested the Majid and Dezful anti-missile systems in an exercise meant to simulate a cruise missile attack. Iran’s conventional army, the Artesh, and the IRGC participated.

Space program: In February, Iran announced the successful launch of the Zoljaneh, a rocket capable of putting satellites into orbit. The United States expressed concern over the test because satellite launch vehicles incorporate technologies that can be used in ballistic missiles.

In June, however, Iran failed to launch a satellite into orbit, according to the Pentagon. The attempt appeared to be the fourth consecutive failure of the Simorgh rocket, according to Jeffrey Lewis of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies.

Annual War Game: Iran tested a wide variety of weapons, including cruise missiles, torpedoes and suicide drones, during an annual war game between November 7 and 9. The Zolfaghar-1400 exercise was held around four key waterways – the Strait of Hormuz, the Sea of Oman, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean – in an area totaling more than 386,000 square miles (1 million square kilometers). Iran’s conventional navy, army, air force and air defense force participated in the war game, although the IRGC did not.

On Iran-U.S. Naval Encounters

Iranian naval forces harassed U.S. forces at least four times in 2021.

- April 2: Three Iranian fast-attack boats and one ship, the Harth 55, approached two U.S. Coast Guard ships, the Monomy and the Wrangell, in international waters in the southern Persian Gulf. The Iranian vessels maneuvered away after three hours of the U.S. forces issuing warnings and conducting defensive maneuvers.

- April 26: The USS Firebolt, a patrol ship, fired warning shots after three IRGC fast-attack boats came within 68 yards of it and the Baranoff, a Coast Guard patrol boat. The incident occurred in international waters of the Persian Gulf. U.S. Navy vessels had not fired a warning shot on Iranian ships since July 2017.

- May 10: The Maui, a Coast Guard cutter, fired 30 warning shots after 13 IRGC Navy fast boats came within 150 yards of six U.S. military vessels, which were escorting the guided-missile submarine Georgia. Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby said that the number of Iranian boats involved was notably higher than in recent encounters.

- Nov. 10: An Iranian naval helicopter circled dangerously close to the USS Essex in the Gulf of Oman. The Essex was able to continue its operations without incident.

On Iran-Israel Naval Incidents

Iran and Israel reportedly continued tit-for-tat attacks on each other’s cargo ships, part of a wider shadow war. Since 2019, both countries appeared to calibrate their attacks to minimize the risk of killing the crew or sinking the ship. But two crew members were killed in an alleged Iranian strike on a ship in July.

- Feb. 26: The Israeli-owned Helios Ray cargo ship was damaged by two limpet mines in the Gulf of Oman. Israel blamed Iran for the attack.

- March 10: An Iranian container ship, the Shahr-e Kord, was hit by an explosive object in international waters in the eastern Mediterranean. It caused a small fire but no casualties. Iran blamed Israel.

- March 25: The LORI, an Israeli-owned cargo ship, was struck by a missile in the Arabian Sea. A senior Israeli defense official claimed that the Revolutionary Guards had fired the missile, which caused minimal damage.

- April 6: An Iranian ship, the Saviz, was damaged by a mine planted on its hull in the Red Sea near Djibouti. The vessel had been floating off the coast of Yemen for several years and was allegedly used as a forward base by the Revolutionary Guards. Israel reportedly conducted the attack in retaliation for previous Iranian strikes, according to The New York Times.

- April 13: The Hyperion Ray, an Israeli-owned cargo ship, was struck by a missile or an unmanned drone near the Fujairah port in the United Arab Emirates. There were no casualties, and the ship continued on its route. The ship was attacked two days after Israel allegedly sabotaged the Natanz nuclear facility. Foreign Minister Zarif had vowed “revenge” on Israel.

- July 3: The CSAV Tyndall, a formerly Israeli-owned cargo ship, was struck by either a missile or an unmanned drone in the Indian Ocean. There were no casualties, but the ship suffered minor damage. Israeli security officials believed that Iran was responsible for the attack, Haaretz reported.

- July 29: The Mercer Street—an oil tanker owned by a Japanese company but was managed by Zodiac Maritime, which is headed by an Israeli shipping magnate—was attacked off the coast of Oman. Israeli officials told The New York Times that multiple Iranian drones were involved in the attack, which killed one British national and one Romanian national.

On Cybersecurity

Western governments, security firms and software companies exposed several hacking attempts linked to the Islamic Republic. And Iran was hit by two sophisticated cyber attacks, one which targeted Iran’s transportation sector and another that disrupted sales at all 4,300 gas stations.

- Feb. 23: Twitter removed 238 accounts operating from Iran after investigating Iranian efforts to interfere in the 2020 presidential election. The accounts were suspended for “various violations of our platform manipulation policies,” the social media company said.

- March 16: The Office of the Director of National Intelligence said that it had “high confidence” that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei authorized a cyber influence campaign during the 2020 presidential election. The online operation was intended to “undercut former President Trump's reelection prospects - though without directly promoting his rivals.”

- March 30: The hacking group dubbed Charming Kitten (aka Phosphorous) targeted two dozen medical researchers in the United States and Israel, the cybersecurity group Proofpoint reported. Iranian hackers impersonated a prominent Israeli physicist and sent spear phishing emails to medical professionals.

- May: A hacking group dubbed Agrius had launched cyberattacks on Israeli targets since December 2020, SentinelLabs researchers reported. The group, allegedly linked to Iran, tried to deploy malware that would erase data on infected devices.

- May: A hacking group called N3tw0rm launched ransomware attacks against H&M Israel and other Israeli companies. The group appeared to be related to Pay2Key, an Iran-linked group that claimed previous attacks on Israel Aerospace Industries and the Israeli cybersecurity company Portnox.

- June 22: The United States seized three dozen web addresses affiliated with Iran and its proxies, including English-language Press TV. Thirty-three websites operated by the Iranian Islamic Radio and Television Union (IRTVU) conducted "disinformation campaigns and malign influence operations," the Justice Department said in a statement. Three others were used by Kataib Hezbollah, an Iraqi Shiite militia group backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards.

- July 9-10: On July 9, hackers caused chaos at Iranian train stations nationwide by posting fake messages about cancellations on display boards. The messages urged passengers to call 64411, the number for a hotline run by the Supreme Leader’s office. The next day, websites tied to the Ministry of Roads and Urbanization reportedly went down. Iran blamed Israel and the United States.

- July 15: Facebook took down nearly 200 fake accounts used by Iranian hackers to target U.S., British and European military and defense personnel. The hackers, known as Tortoiseshell, sought to infect victims’ computers with malware and steal their login information. The malware used by the hackers was developed by Mahak Rayan Afraz (MRA), a company in Tehran with ties to the IRGC, according to Facebook’s cybersecurity team.

- July 26: Five documents allegedly outlining Iran's research on offensive cyber operations were leaked to Britain’s Sky News. The reports were reportedly compiled by Intelligence Team 13, a group within the Revolutionary Guard's cyber unit, Shahid Kaveh. They detailed how Iran planned to hack critical infrastructure, including water filtration, fuel supply systems and maritime communications. One report examined vulnerabilities in "smart" building management systems in the United States, France and Germany.

- Oct. 11: Microsoft announced that a hacking group linked to Iran attempted to gain access to more than 250 accounts “with a focus on U.S. and Israeli defense technology companies, Persian Gulf ports of entry, or global maritime transportation companies with business presence in the Middle East.” Some of the targeted companies produce drones, military-grade radars, and other advanced equipment. Fewer than 20 of the targets were compromised.

- Oct. 26: A cyberattack knocked out the system that allows Iranians to use government-issued cards to purchase fuel at a subsidized rate. The outage impacted all 4,300 gas stations in Iran. Consumers either had to pay the regular price, more than double the subsidized rate, or wait for stations to reconnect to the central distribution system. Digital billboards in Tehran and Isfahan were also compromised. Some displayed the message, “Khamenei! Where is our gasoline?” Iran blamed Israel and the United States.

- Nov. 16: Microsoft said that six distinct groups linked to Iran deployed ransomware, which often encrypts data until a victim sends payment to the hackers. Microsoft noted that one hacking group was trying to gain access to systems of defense companies that support U.S., E.U., and Israeli government partners.

- Nov. 17: U.S., Australian and British cybersecurity agencies said that an Iran-backed hacking group was targeting Australian organizations and the transportation and healthcare sectors in the United States. The hackers were trying to access their computer networks by exploiting vulnerabilities in software developed by Microsoft and Fortinet (a cybersecurity firm).

- Nov. 18: Microsoft reported a significant rise in Iranian cyber attacks against IT services companies in 2021. Microsoft sent 1,647 notifications to more than 40 companies in response to Iranian targeting compared to just 48 notifications in 2020. Most of the targeted companies were based in India. Several were based in Israel and the United Arab Emirates.

- Nov. 18: The United States sanctioned six Iranian men and one entity for attempting to interfere with the 2020 U.S. presidential election. They had tried to undermine voter confidence in the electoral process by disseminating disinformation on social media, sending threatening emails and more, the Treasury Department charged.

On the Economy

Iran’s economy grew slightly in 2021, despite U.S. sanctions. The International Monetary Fund estimated that Iran’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased 2.5 percent. Iran fell far short of its goal to export 2.3 million barrels per day of oil.

To incentive buyers to defy U.S. sanctions, Iran reportedly sold oil at a steep discount – four to seven dollars cheaper per barrel compared to global benchmarks. Chinese companies bought most of Iran’s exports, which averaged approximately 1.2 million barrels per day, according to TankerTrackers.com, which tracks transfers using satellite imagery.

Iran boosted non-oil trade in 2021. In the first eight months of the Persian year (March 21 to November 21), Iran exported $31.1 billion in goods and imported $32 billion in goods – a 41 percent increase in overall trade compared to the same period last year.

The business climate improved as Iran vaccinated more of its population. On December 5, President Raisi announced that 100,000 businesses had reopened since he took office in August. But unemployment, estimated at 10 percent, was about the same as in 2020.

Inflation, estimated at almost 40 percent for the year, was a chronic problem. Salaries did not keep up with prices. As a result, many households increasingly struggled to afford basic goods. As of November 2021, food inflation was at 59.6 percent.

Inflation, estimated at almost 40 percent for the year, was a chronic problem. Salaries did not keep up with prices. As a result, many households increasingly struggled to afford basic goods. As of November 2021, food inflation was at 59.6 percent.

The pressure was reflected in labor unrest. In June, thousands of workers from 60 companies in the oil and petrochemical industry went on strike to demand better wages and working conditions. In December 2021, teachers and supporters took to the streets of 119 cities, including Tehran, Shiraz and other urban centers, to demand fair compensation.

The value of Iran’s currency, the rial, fluctuated amid Iran’s political transition and uncertainly about sanctions relief and restoring the 2015 nuclear deal. The rial depreciated some 15 percent against the dollar between January and mid-December. At the start of 2021, one U.S. dollar was trading for 257,000 rials on the open market. In mid-December, one dollar was trading for around 302,500 rials, close to a record low set in October 2020 when oil prices fell.

On Public Health

Iran struggled to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic throughout 2021. Iran began its vaccination campaign in February. But a fourth wave of infections began in March before many shots were administered. Iran faced a vaccine shortage, which was exacerbated by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s ban on the import of vaccines from the United States and Britain. The development of several domestically produced vaccines also lagged. When the fifth and deadliest wave of infections hit in July 2021, only two percent of the population of some 85 million had been vaccinated.

In the early days of his presidency, Raisi’s top priority was fighting Iran’s the fifth wave. More than 38,000 new cases and 400 deaths were reported on August 5, the day that he took office. Three days later, Raisi set an example by publicly receiving his first dose of the CovIran Barekat vaccine, the first domestic vaccine.

The government took aggressive measures – including curtailing travel between cities and a six-day national lockdown – to stem the spread of the highly contagious Delta variant in August. Domestic production of vaccines remained slow, but Iran ramped up imports. In August, Supreme Leader Khamenei appeared to soften his position on American and British vaccines. The health ministry clarified that AstraZeneca, Moderna and Pfizer vaccines could be imported as long as they were not produced in the United States and Britain.

By mid-December, Iran had received more than 150 million doses, mainly purchased from China. And nearly 60 percent of the population was fully vaccinated. In 2021, more than 75,000 people died from COVID-19, according to official tallies. But the daily death and case rates trended downward as Iran administered more shots.

On the Environment

For years, Iran has suffered from water scarcity caused largely by decades of poor planning and mismanagement. The summer of 2021 was one of the driest in five decades. Rainfall was down 40 percent from the annual average, the government reported in July. Rainfall was down in Iran’s eastern and southern province even more – from 50 percent to 85 percent.

As a result, more than 300 cities faced water shortages. Some 8,400 villages depended on tankers for water, compared to some 5,500 in 2020. At the same time, temperatures reached as high as 122 degrees (50 degrees Celsius), and several major cities were hit by rolling power outages. The water shortages first sparked sporadic protests by farmers in Isfahan, Yazd, Khuzestan, Lorestan, and Charmahal and Bakhtiari provinces.

On July 15, residents of southwestern Khuzestan province protested the water shortage and power outages. Protestors gathered in the streets of several cities, including the provincial capital of Ahvaz. The protests continued daily for two weeks in Khuzestan, despite a harsh crackdown. Amnesty International reported that security forces killed at least eight protesters and bystanders in seven different cities in Khuzestan. People also demonstrated in Tehran and several other cities in solidarity with the province, which is home to Iran’s Arab minority. Arab activists have long accused the central government, dominated by Persians, of systematic discrimination.

On November 8, farmers started a sit-in on the dry Zayanderoud riverbed in Isfahan city to protest water shortages. Thousands of residents joined the peaceful demonstrations. The authorities appeared to tolerate the sit-in, which was covered by state media, until November 25, when security forces broke up the camp.

The timeline entries on cyber issues builds on a report originally compiled by Andrew Hanna. The timeline entries on the Israel-Iran conflict at sea builds on research by Julia Broomer.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of “The Iran Primer” at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Photo Credits: Raisi press conference via Tasnim News Agency (CC by 4.0); Rafael Grossi by Dean Calma / IAEA via Flickr (CC BY 2.0); Kaman 22 via Tasnim News Agency (CC BY 4.0);