Garrett Nada

Iran went from being a pariah to a player in international affairs in 2015. The turning point was the final nuclear deal between Iran and six world powers brokered in July. It “changed the way the international community looked at Iran,” Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif

said in December. The deal, just five months old, has already helped pave the way for Iran’s comeback on the international scene.

Nuclear Deal

On July 14, Iran and the world’s six major powers —Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States— reached a final deal on Tehran’s controversial nuclear program. Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Iran is to curtail its nuclear program and increase transparency in return for sanctions removal. The deal, subsequently endorsed in a U.N. Security Council

resolution, culminated 20 months of intense and difficult negotiations.

On October 18,

Adoption Day, Iran and the so-called P5+1 countries began taking steps to prepare for the deal’s implementation. In an October 21 letter to President Rouhani, Supreme Leader Khamenei

approved the deal under certain conditions. But he warned that any new sanctions on Iran would be considered a violation of the agreement.

In November, the U.N. nuclear watchdog confirmed that Iran was removing centrifuges at the Natanz and Fordo facilities. In December, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) released a long-awaited report on Iran’s past nuclear activities. The IAEA concluded that Iran had worked on a “range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device,” despite its denial of any work on a nuclear weapons program. The most “coordinated” work was done before 2003, but some activities continued until 2009. The IAEA board of governors voted to close the probe on Iran’s past activities on December 15.

Iran aims to fulfill its commitments under the deal as soon as January 2016. So “Implementation Day” —when certain U.N., E.U., and U.S. sanctions will be lifted or suspended —is also

expected to occur in January.

United States

At the close of 2015, the future of U.S.-Iran relations was uncertain. The nuclear deal had not changed the anti-American rhetoric in Iran. Indeed, the pace of vitriol noticeably increased. “U.S. officials seek negotiation with #Iran; negotiation is means of infiltration and imposition of their wills,” Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said in September, captured in a string of tweets on his English-language

account.

Hardliners in Parliament took a particularly tough stand. On November 2, 192 out of 290 lawmakers signed a letter vowing not to abandon the slogan “Death to America (also translated as “Down with the USA”),” first popularized after the United States took in the ailing shah in 1979 and Iranian students seized the American embassy. On the 36th anniversary of the takeover, in November 2015, hardliners in parliament

declared, “The honorable nation of Iran will under no circumstances be willing to put aside the ‘Death to America’ slogan because of the agreement on the nuclear issue; a slogan that has become a symbol of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the entirety of struggling nations have held Islamic Iran as a model for their own fight.”

The conflicting signals out of Tehran reflected a wider debate over the nature of Iran’s relationship with the United States. Hardliners were aggressive against their own government officials over contact with the United States after the nuclear deal. Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s brief handshake with President Obama at the United Nations in September caused a firestorm. In an Instagram post, lawmaker Hamid Rasaee likened the encounter to embracing Satan (see below). The text reads, “Mr. Zarif! Did you sign the nuclear deal with the same hand?”

The supreme leader also counseled against further engagement with the United States. Despite the limited U.S. sanctions relief, he warned in November for Iranians to “seriously avoid importing consumer goods from the United States.” Khamenei also cautioned against getting sucked into the U.S. agenda in the Middle East. “U.S. goals in the region are diametrically opposed to Iran’s goals. Negotiation with the U.S. on the region is pointless,” he said in a speech on November 1. Two day later, Khamenei

warned that Washington has attempted to “beautify” its image and “pretend” that it is no longer hostile to Iran. The United States “will not hesitate” to destroy Iran if given the chance, he

said.

President Rouhani took a softer line. In an

interview with CBS, he said the “Death to America” chant “is not a slogan against the American people.” He said it was a reaction to longstanding U.S. support for the shah as well as Saddam Hussein during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. “People will not forget these things. We cannot forget the past, but at the same time our gaze must be towards the future,” Rouhani said. He acknowledged the potential for future talks. “Many areas exist where in those areas it's possible that common goals, or common interests, may exist,” he told

CBS. Hardliners have been concerned that the Islamic revolution will be compromised by Rouhani’s willingness to engage with the United States again.

Rouhani also indicated an openness to discussing the detention of U.S. citizens in Iran, a key point of contention. “If the Americans take the appropriate steps and set them free, certainly the right environment will be open and the right circumstances will be created for us to do everything within our power and our purview to bring about the swiftest freedom for the Americans held in Iran as well,” Rouhani told CNN on September 27, when he was in New York for the U.N. General Assembly. As of December, four Iranian-Americans were detained, including Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian, businessman Siamak Namazi, former U.S. Marine Amir Hekmati, and Rev. Saeed Abedini. A fifth American, former FBI agent Robert Levinson, has been missing since 2007, when he was last sighted on an Iranian island.

Europe

In 2015, the European Union began exploring ways to build on the nuclear deal. E.U. foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini expressed a desire to integrate Iran into a regional framework to solve crises in the Middle East and to work cooperatively to confront the threat of the Islamic State (ISIS). Key E.U. member states began upgrading their diplomatic relations with Tehran. More than a dozen European nations

reached out to Iran with high profile visits and phone calls with top officials. Representatives from European businesses also began flocking to Iran in anticipation of sanctions relief and the reopening of one of the Middle East’s largest markets.

Some of Iran’s old trade partners were the first to reach out. German vice chancellor and economics minister Signmar Gabriel arrived in Tehran on July 20, becoming the first high ranking Western official to visit after the July 14 announcement of the nuclear deal. Despite taking a

tough stance during the nuclear negotiations, France also moved quickly. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius met with officials in Tehran just 15 days after the nuclear deal was signed. Italian officials visited Tehran in early August seeking to boost trade relations.

On August 23, British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond traveled to Tehran to reopen the British Embassy, which had been closed since 2011. The Iranian embassy in London was reopened the same day. In a joint press conference with Hammond, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that Iran and Britain had “entered a new phase of relations based on mutual respect.” Hammond was the first British Foreign Secretary to visit Iran in 12 years.

After receiving invitations from Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and French President Francois Hollande, President Rouhani scheduled visits to Italy, the Vatican, and France from November 14 to 17. It would have been his first trip to Europe as president. But it was

postponed in light of the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris.

Russia

Russia and Iran strengthened their relationship in 2015, largely due to shared interests in supporting the Assad regime in Syria and countering Western powers. In January, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu visited Tehran and signed an agreement with his counterpart Hossein Dehghan to expand military ties. “Iran and Russia are able to confront the expansionist intervention and greed of the United States through cooperation, synergy and activating strategic potential capacities,” Dehghan

said.

In April, Russian President Vladimir Putin

removed five-year-old restrictions on shipping S-300 surface to air missiles to Iran. Russia began

transferring the systems to Iran in November. One of Putin’s aides

predicted a major growth in Iran-Russia weapons contracts after international sanctions are lifted as part of the nuclear deal. “Considering the fact that this is a large country [Iran] with large military forces, we are talking very big contracts, worth billions,” said Vladimir Kozhin in December.

Also in April, Russia

announced the implementation of an oil-for-goods barter deal with Iran. Iran would export up to 500,000 barrels of crude oil to Russia per day in exchange for goods an equivalent value. But as of late 2015, implementation was

stalled due to low oil prices.

In September, Russia, Iran, Iraq and Syria began

sharing intelligence related to the fight against ISIS. Russia carried out its

first air strikes in Syria on September 30 and continued to bomb targets through the end of the year. Moscow said it was targeting terrorist groups, including ISIS and the Nusra Front. But U.S. officials reportedly

said Russia was targeting CIA-backed rebel groups. In mid-October, Russia and Iran coordinated to

help pro-government forces retake Aleppo and the surrounding countryside from rebel groups. The commander of Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards Qods Force, Qassem Soleimani,

reportedly visited Moscow

twice in 2015 to discuss Syria policy and strategy with Putin.

On November 23, Putin

arrived in Tehran to discuss the Syrian crisis, the fight against ISIS and implementing the nuclear deal. Putin’s visit, his first in eight years, was timed to coincide with an international gas summit. Putin and Rouhani signed seven memoranda of understanding. Russia and Iran agreed to facilitate travel for their citizens to either country. The other memoranda were related to health, railways, banking and insurance, power generation and transmission, and groundwater exploration.

China

In 2015, Iran and China took steps to increase cooperation across several sectors. On trade, China remained Iran’s biggest oil buyer in 2015. It

bought 536,500 barrels per day of Iranian crude from January through October. From January through October, Iran

reportedly extended crude oil contracts with its top two Chinese buyers into 2016 and shopped for other potential buyers. The energy hungry giant is positioned to remain a key investor in Iranian oil and gas infrastructure. In November, China’s state-owned railway

proposed a high-speed rail link that would carry passengers and cargo between the two countries.

Iran was accepted as a founding member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) in April. The entity was seen as a potential rival to the largely U.S.-led Word Bank and Japan-led Asian Investment Bank. In October, Iran purchased 2.8 percent of shares in the AIIB. Tehran also

intends to join the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) New Development Bank established in July.

Iran is also likely to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2016. In July, the groups’ secretary general

said Iran’s membership request would be placed on the agenda after implementation of the nuclear deal begins, currently expected in January. Membership would further cement Iran’s place in the Russian and Chinese economic spheres.

A string of high-level contacts in 2015 indicated that Beijing and Tehran aim to ramp up military cooperation as well. In October, the deputy chief of staff of the People’s Liberation Army led a

delegation to Tehran. Admiral Sun Jianguo

said it aimed to “further promote friendship, deepen cooperation and exchange views with Iran on bilateral military ties and issues of mutual concern.” In November, Iran’s air force commander, Brigadier Hassan Shah Safi, met his counterpart in

Beijing and toured state companies manufacturing aircraft and air defense hardware. In December, a high-ranking Chinese military

delegation visited Tehran to discuss naval cooperation.

South and Central Asia

Iran had greater success strengthening ties with its eastern neighbors in 2015. India and Pakistan were among the first countries Zarif visited after the nuclear deal’s announcement in July.

India remained Iran’s top oil

buyer after China in 2015. As of October, it was India’s seventh largest

supplier. Before international sanctions severely curtailed Iran’s exports around 2010, it was India’s second largest supplier. “India has been a friend of Iran in difficult times, and we don’t forget that,” Zarif

told reporters in New Delhi in August. India moved to secure its interests in Iran’s natural gas reserves, the second-

largest in the world. In December, a consortium of Indian companies reached an initial agreement to

develop the Farzad B gas field under a $3 billion contract. Tehran and Delhi were also reportedly discussing a

plan to build a $4.5 billion undersea gas pipeline to connect southern Iran to western India.

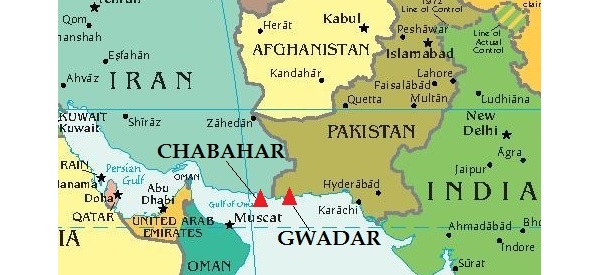

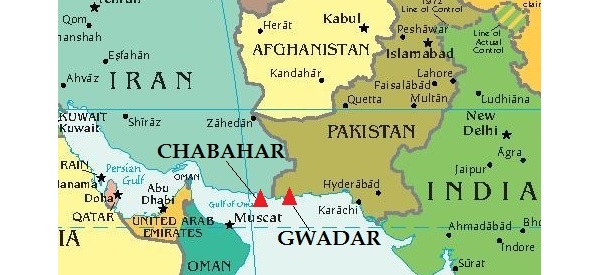

In an effort to increase bilateral trade of other goods, India and Iran signed a memorandum of understanding in May to develop the strategically important Chabahar port on Iran’s southern coast. In October, India said it was ready to invest some $196 million in Chabahar, but

stipulated that investments would depend on the price of Iran’s natural gas. India and Iran both aim to seal the deal by January. Just 44 miles west of Pakistan’s Gwadar port, Chabahar could help India expand trade ties into Central Asia. India would also be less dependent on land routes through Pakistan to Afghanistan.

India-Iran economic cooperation is likely to continue expanding in 2016, when both are

expected to become members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The intergovernmental group, founded in 2001, promotes cooperation among its six member states and six observer states in the political, economic, cultural, security and science spheres. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Rouhani actually met on the sidelines of a BRICS/SCO

summit in July.

Tehran was also keen on strengthening ties with Islamabad. Zarif visited Pakistan three times in 2015. In April, Zarif

discussed the Yemeni crisis and Iran-Pakistan border security with Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and other top officials. The shared 500-mile border runs through the homeland of the Baloch —a Sunni ethnic group that has waged a decades-long insurgency against both countries.

In August, Zarif met with Sharif in Islamabad again. Zarif

said they discussed ways to increase cooperation “in sectors ranging from oil to gas, energy, transportation and others.” Security cooperation was also high on the agenda again. Islamabad

assured Iran of its resolve to start work on its part of the gas pipeline. Iran completed its part of the $1.5 billion project in 2013, but Pakistan stalled due to international sanctions on Iran’s nuclear program.

In December, Zarif

visited Islamabad for the fifth Heart of Asia – Istanbul Process Ministerial Conference aimed at helping bolstering regional security and economic cooperation with a focus on Afghanistan. Representatives from 14 countries

participated.

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani visited Tehran in April. He and Rouhani

announced plans to enhance security cooperation to counter ISIS and drug smuggling. They

agreed to expand economic cooperation, especially regarding trade, transit, energy, industry and mining. Both countries had a shared interest in shoring up security along their porous 585-mile border. Smugglers have long taken advantage of the difficult terrain to sneak drugs into Iran. In 2015, however, Tehran became increasingly concerned about the possibility of a border attack by ISIS. In November, Iran conducted

exercises near the border to simulate one.

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP.

Photo credits: P5+1 officials in Vienna by US Dept of State via Flickr Commons; Rouhani photos via President.ir

Some of Iran’s old trade partners were the first to reach out. German vice chancellor and economics minister Signmar Gabriel arrived in Tehran on July 20, becoming the first high ranking Western official to visit after the July 14 announcement of the nuclear deal. Despite taking a tough stance during the nuclear negotiations, France also moved quickly. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius met with officials in Tehran just 15 days after the nuclear deal was signed. Italian officials visited Tehran in early August seeking to boost trade relations.

Some of Iran’s old trade partners were the first to reach out. German vice chancellor and economics minister Signmar Gabriel arrived in Tehran on July 20, becoming the first high ranking Western official to visit after the July 14 announcement of the nuclear deal. Despite taking a tough stance during the nuclear negotiations, France also moved quickly. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius met with officials in Tehran just 15 days after the nuclear deal was signed. Italian officials visited Tehran in early August seeking to boost trade relations.  In September, Russia, Iran, Iraq and Syria began sharing intelligence related to the fight against ISIS. Russia carried out its first air strikes in Syria on September 30 and continued to bomb targets through the end of the year. Moscow said it was targeting terrorist groups, including ISIS and the Nusra Front. But U.S. officials reportedly said Russia was targeting CIA-backed rebel groups. In mid-October, Russia and Iran coordinated to help pro-government forces retake Aleppo and the surrounding countryside from rebel groups. The commander of Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards Qods Force, Qassem Soleimani, reportedly visited Moscow twice in 2015 to discuss Syria policy and strategy with Putin.

In September, Russia, Iran, Iraq and Syria began sharing intelligence related to the fight against ISIS. Russia carried out its first air strikes in Syria on September 30 and continued to bomb targets through the end of the year. Moscow said it was targeting terrorist groups, including ISIS and the Nusra Front. But U.S. officials reportedly said Russia was targeting CIA-backed rebel groups. In mid-October, Russia and Iran coordinated to help pro-government forces retake Aleppo and the surrounding countryside from rebel groups. The commander of Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards Qods Force, Qassem Soleimani, reportedly visited Moscow twice in 2015 to discuss Syria policy and strategy with Putin.