Walter Posch

- Since the early 1990s, relations between the European Union and Iran have correlated with Iran's domestic situation. Relations have grown closer during times of political openings in Tehran and tenser when the regime becomes more repressive.

- To address political, economic and human rights issues, the European Union has preferred to conduct relations with Iran in a dialogue format, instead of through the usual Trade and Cooperation and Political Dialogue Agreements.

- Britain, France and Germany took the diplomatic lead on nuclear negotiations with Iran. They established a framework that kept the door open for indirect and direct negotiations between the United States and Iran.

- After 2005, the nuclear controversy surpassed all strategic issues—energy, Middle East security, trade and even human rights—in EU-Iran relations. As a result, the EU policy increasingly resembled U.S. policy on Iran. A decade of independent and imaginative EU policy ended with the passage of U.N. Resolution 1929 in June 2010.

- Between 2010 and 2013, the European Union imposed increasingly tight sanctions on Iran, including an oil embargo, over its nuclear program. Talks between Iran and the EU3+3—Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States (also known as the P5+1)—failed to produce an agreement on the nuclear issue.

- New diplomatic efforts following the 2013 election of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani yielded an interim nuclear deal in November 2013 and a final deal in July 2015. The EU high representative on foreign policy — along with the EU “Big Three” (Britain, France and Germany) —played a critical role in the negotiations.

Overview

For decades, the European Union’s policy of engaging Tehran differed markedly from the U.S. policy of containing or isolating Iran. At the height of European engagement, EU foreign policy chief Javier Solana often acted as negotiator with Iran on behalf of the entire international community. The EU’s main function in the nuclear crisis was accomplished when the United States expressed willingness to talk directly to Iran. But the more the Iranians stalled, the more the EU followed the U.S. lead and intensified sanctions against the Islamic Republic—even when it ran counter to Europe’s own economic and strategic interests in the region.

The EU played a crucial role in the new diplomacy between Iran and the world’s six major powers precipitated by the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani. EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton led the talks that resulted in the November 2013 interim nuclear agreement. And her successor, Federica Mogherini, chaired the talks that led to the July 2015 final deal.

In 2015, the EU began exploring ways to build on the nuclear deal. Mogherini expressed interested in integrating Iran into a regional framework to solve crises in the Middle East and work cooperatively to confront the threat of the Islamic State (ISIS). Key EU member states, such as the United Kingdom, began upgrading their diplomatic relations with Tehran. And representatives from European businesses began testing the ground in Iran in anticipation of sanctions relief and the reopening of one of the Middle East’s largest markets.

On Jan. 16, 2016, the U.N. nuclear watchdog confirmed that Iran had taken the necessary steps to implement the nuclear deal. Implementation Day triggered the lifting or suspension of certain EU, U.S. and U.N. sanctions on Iran. Less than 10 days later, President Rouhani made his first visit to Europe as president.

The Rafsanjani era 1989-1997

After a decade of war and revolutionary turmoil, President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani began pushing Iran toward normalcy in both domestic and foreign policy when he was elected in 1989. Iran’s new tone, combined with its geopolitical and economic importance, convinced the European Union—as distinguished from individual member states—to consider intensifying relations. In 1992, the European Council made the formal decision to reach out to Iran. A host of issues still caused serious tensions, including Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa calling for the death of Salman Rushdie, author of “The Satanic Verses.” So the EU initiated a “critical dialogue,” rather than try to establish formal ties through a Trade and Cooperation Agreement or a Political Dialogue Agreement–as the EU would with other countries.

The “critical dialogue” reflected both components of the new EU policy: It was critical because the Europeans brought up the most worrisome issues with Iran—its abysmal human rights record, support for terrorism, opposition to the Middle East peace process and proliferation issues. But it was still a dialogue in which Europeans and Iranians talked and listened to each other.

The “critical dialogue” came under fire from many in Europe, the United States and Israel. The main complaint was that the diplomatic dialogue was cheap cover for booming European business relations with the oil-rich Islamic Republic. Yet the “critical dialogue” did force the Iranians to look at human rights issues – and admit that there was an issue at all. But over the next five years, EU-Iran relations deteriorated again. A 1997 German court’s verdict against Iranian officials for involvement in terrorist activities was the turning point. Iran’s unacceptable reaction to the verdict led to the pull-out of all European ambassadors from Tehran. Relations seemed beyond repair, at least from the EU vantage point.

The reformist era 1997-2002

The surprise election of President Mohammad Khatami in 1997 changed the Iranian political climate at home and with the outside world. His new reform agenda made re-engagement possible. The EU decided to revamp the “critical dialogue” and launch a new “comprehensive dialogue.” Within this format, EU and Iranian officials met twice a year at the level of under-secretary of state. The range of issues was enhanced; human rights and non-proliferation issues were put higher on the agenda.

After Khatami’s 2001 re-election, the EU moved to further intensify the relationship. It pressed for significant positive steps on the thorniest issues between Iran and the outside world. During this period, EU-Iran relations flourished at all levels— economic, social, academic and cultural. Impressed by the serious debate inside Iran on democracy and human rights, many Europeans hoped that further engagement—including Trade Cooperation and Political Dialogue Agreements—would facilitate even more democratic openings in Iran.

But this second diplomatic effort also suffered a serious setback after revelations in 2002 that Iran had undeclared nuclear sites at Natanz and Arak. From then on, Iran’s controversial nuclear program took priority over all other policy issues.

Nuclear Issues and Diplomatic Escalation 2002-2013

Iran became a critical diplomatic test case for the young EU after the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. Given the disclosure of a secret Iranian nuclear program, European decision-makers could not rule out another unilateral U.S. military attack, this time on Iran. But many Europeans were concerned that American unilateralism might also weaken the system of controls and verification conducted by the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The EU felt pressure to use its contacts with both Iran and the United States to prevent another Middle East war, and also prove that it could act as a united, important and independent actor on the international stage. Combining these partially conflicting agendas was not easy in light of the often cumbersome and consensual EU decision-making processes.

In the autumn of 2003, the EU’s “Big Three”—Britain, France and Germany—launched an initiative to defuse the crisis created by Iran’s secret nuclear program. The three foreign ministers travelled to Tehran to convince the regime to take three pivotal steps: suspend uranium enrichment, detail the full scope of its nuclear program and facilities and sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Additional Protocol, which provided for more intrusive IAEA inspections. The European Council's secretary general and foreign policy chief, Javier Solana, joined the negotiating team. The EU-3 finalized the Paris Agreement with Iran on Nov. 15, 2004. The Paris Agreement was a major turning point proving the effectiveness of joint EU diplomacy. The EU-3 initiative became the EU's main

modus operandi for transatlantic diplomacy with the United States, as well as nuclear diplomacy with Iran.

For the Europeans, the Khatami presidency was a mixed blessing. He appeared to be willing to deal with the international community, but he also faced a growing backlash with each compromise. After Iran signed the Paris Agreement, the nuclear issue became the most divisive foreign policy issue among Tehran’s many factions. Hardliners argued that the nuclear program was the key to Iran’s technological progress as well as the symbol of its sovereignty and international standing. They accused the reformists of selling out Iranian national interests.

The diplomatic tide turned after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran’s 2005 presidential election. Tehran effectively renounced the Paris Agreement. The new government instead announced plans to again enrich uranium, the most controversial step in its nuclear program. The rejection was not simply due to a new president. The regime also had a basic disagreement with the outside world on its rights under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Ahmadinejad had an impact on relations with Europe in other ways. His inflammatory remarks on Israel and denial of the Holocaust, which are particularly sensitive issues in Europe, poisoned the diplomatic climate. They also destroyed the inroads achieved during the Khatami presidency. Iran’s supreme leader ultimately makes key decisions. Yet there was a striking difference in tactics once Ahmadinejad was elected. During Khatami’s presidency, Iran meticulously avoided actions on its nuclear program that would lead Iran to be referred to the U.N. Security Council. But Ahmadinejad proved a bold risk-taker.

In early 2006, Iran was referred to the U.N. Security Council because of its failure to provide information on its past covert nuclear program. The EU continued to take the lead in trying to convince Tehran to cooperate with the international community. Solana, the EU foreign policy chief, became the sole negotiator with the Iranians. In 2006 and in 2008, Solana presented offers for a negotiated solution that included several economic and diplomatic incentives, in both cases backed by the United States and the U.N. Security Council. Tehran rejected both packages, even though the price was a new round of sanctions.

In 2009, the EU and the United States jointly made a third offer to help Iran at talks in Geneva, the first time an American envoy was present. This time the deal introduced a two-step plan. The first phase would provide badly needed fuel for Iran’s research reactor, which it used to produce isotopes for medical purposes, in exchange for Iran transferring some 80 percent of its enriched uranium abroad for reprocessing into fuel rods. The process would allow time for step two, which centered on talks about Iran’s entire nuclear program. Tehran initially embraced the offer, but soon backed down under pressure from both conservatives and reformers at home.

New Diplomacy 2013 -

Two key factors facilitated new diplomatic efforts to solve the nuclear issue in 2013: back channel negotiations between the United States and Iran that began in 2009, and the election of centrist Hassan Rouhani to Iran’s presidency in June 2013. EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton led the EU3+3 in talks with Iran that eventually resulted in the November 2013 interim agreement, or Joint Plan of Action. Iran committed to halting the most sensitive aspects of its program and allowing expanded U.N. nuclear inspections in return for modest sanctions relief.

The EU, represented by Federica Mogherini starting in November 2014, continued to be a major player in the negotiations. Mogherini’s staff helped craft bridging proposals on technical issues and participated in all the U.S.-Iran bilateral nuclear talks that were also critical to the talks. On July 14, 2015, Iran and the EU3+3 announced that they had reached a final deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In return for sanctions removal, Iran agreed to limit its nuclear program, address questions regarding past nuclear weapons related efforts and be more transparent.

On Jan. 16, 2016, the nuclear deal went into the implementation phase after the International Atomic Energy Agency confirmed Iran’s compliance with the agreement. Implementation Day triggered the lifting or suspension of nuclear-related EU, U.S. and U.N. sanctions. Iran regained access to the international finance system and billions of dollars in frozen assets abroad. It also returned to the oil market.

Trade relations and sanctions

The post-war normalization under Rafsanjani created a relatively friendly business environment in the 1990s. European enterprises were ready to engage in what has been a promising market. The Europeans imported mainly oil from Iran and hoped to be able to invest in Iran’s vast gas supplies. Iran, in turn, bought mostly machinery. Yet business relations with Iran faced many practical obstacles, including an overbearing bureaucracy, weak legal system and the absence of a European Trade and Cooperation Agreement.

Business relations became more complicated under the Ahmadinejad government; international sanctions also had an impact. Starting in 2006, Europe’s Iran policy was increasingly reduced to nuclear issues. Actions in turn focused on sanctions. From 2006 to 2010, the U.N. Security Council passed six resolutions that included four rounds of sanctions. Resolution 1929, passed in 2010, expanded an arms embargo and tightened restrictions on Iran’s financial and shipping sectors related to proliferation-sensitive activities. The EU imposed sanctions in compliance with the resolutions. The following is a rundown of key EU actions.

July 26, 2010: The EU imposed new sanctions on Iran that went further than U.N. resolutions. The decision provided a “comprehensive and robust package of measures in the areas of trade, financial services, energy, transport as well as additional designations for visa ban and asset freeze, in particular for Iranian banks, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL),” according to a press statement.

May 23, 2011: The EU added more than 100 new entities to a list of sanctioned entities and individuals.

Dec. 1, 2011: The EU imposed new sanctions on 180 Iranian officials and companies. The measures were primarily aimed at Iran’s financial system, transport sector and energy sector.

Jan. 23, 2012: The EU agreed to ban Iranian oil imports, effective July 1, and to prohibit EU regulated insurers from covering any ship transporting Iranian oil or petrochemicals.

Oct. 15, 2012: The EU added 34 entities and Iran’s energy minister to its sanctions list, but also removed 10 individuals and entities.

Dec. 21, 2012: The EU added one person and 18 entities allegedly involved with nuclear or ballistic missile activities to its sanctions list and removed two others.

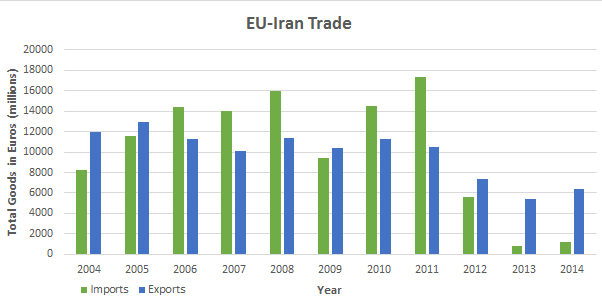

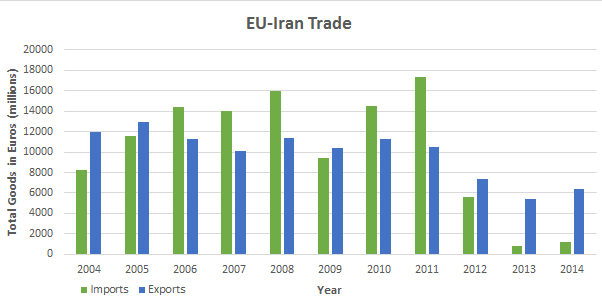

Since the United States had long had a wide array of sanctions on Iran, the new U.N. Security Council resolutions impacted Europe far more. The EU was Iran’s top trading partner until China overtook it in 2010. But the focus on the nuclear issue had two other negative effects: First, it prevented the EU from formulating a cohesive Iran strategy that would also factor in human rights, regional issues and energy.

Second, sanctions ceased to be a tool because they became both the EU's strategy and policy on Iran. The array of sanctions imposed under four U.N. resolutions since 2006 progressively moved toward a containment policy. For Europe, they were also effectively irreversible without U.S. consent. From that perspective, the EU out-sanctioned itself from having any influence with Iran.

*Data source: European Commission

As part of the 2013 interim nuclear deal, the EU suspended certain nuclear-related sanctions on Iran and suspended the prohibition on provisioning insurance and transport of Iranian oil. High level European delegations, including many business people, began turning up in Tehran soon after the July 2015 announcement of the agreement. German and French companies were especially eager to reenter the 80-million-strong Iranian market.

Iran and EU countries stepped up efforts to strengthen economic ties following the nuclear deal’s Implementation Day on Jan. 16, 2016 and the subsequent lifting of nuclear-related EU sanctions. On Jan. 25, 2016, President Rouhani embarked on a five-day trip to Italy, the Vatican, and France. Both France and Italy were major trade partners with Iran before sanctions were tightened in 2010 and 2012. Historically, most Iranian exports to Europe have been energy related. And most EU exports to Iran have been machinery, transport equipment and chemicals.

Around half of the 140 economic

delegations that visited Iran between March and December 2015 were from European countries. The following is a rundown of key visits to Iran by high level European officials after the nuclear deal’s announcement as well as visits by top Iranian officials to EU countries.

On July 28, 2015, EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini arrived in Tehran for a one-day

visit with senior Iranian officials. Mogherini

said the nuclear deal “has the capacity to pave the ground for wider cooperation between Iran and the West.”After meeting with Mogherini, Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that Iran and EU had

agreed to hold talks “over different issues, including energy cooperation…human rights, confronting terrorism, and regional issues.”

Mogherini’s visit coincided with her

op-ed in

The Guardian, in which she argued that cooperation between Iran and the West could help defeat ISIS. “The Vienna deal tells us that we all have much to earn if we choose cooperation over confrontation. Making the most out of this opportunity is entirely up to us,” she wrote.

On Aug. 23, 2015, British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond traveled to Tehran to reopen the British Embassy, which had been closed since 2011. The Iranian embassy in London was reopened the same day. In a joint press conference with Hammond, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that Iran and Britain had “entered a new phase of relations based on mutual respect.”

Hammond was the first British Foreign Secretary to visit Iran in 12 years. He met with Rouhani, Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani, Supreme National Security Council Secretary Ali Shamkhani, and other officials during his visit. Hammond was accompanied by a group of British business leaders hoping to reestablish ties in Iran.

Austrian President Heinz Fischer visited Tehran from Sept. 7 to 9, 2015,

accompanied by Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz, and Economy Minister Reinhold Mitterlehner. Fischer said that he expected bilateral

trade between Austria and Iran to reach $335 million in 2015.

On Nov. 7, 2015, European Parliament chief Martin Schulz met with officials in Tehran, at the invitation of the Iranian parliament. It was the

first time a head of the European Parliament had visited Iran. “The Islamic Republic of Iran is an element of stability in a region full of instability,” Schulz

said during the visit.

On Jan. 25, 2016, Rouhani arrived in Rome and met with Italian President Sergio Mattarella and Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. Iran and Italy signed deals worth some

$18.4 billion for cooperation in energy, infrastructure, shipbuilding, and mining. The two countries signed 14 MoUs, including a deal with the

Parsian Oil & Gas Development Company to upgrade the Pars Shiraz and Tabriz refineries. Iran also signed contracts worth 5.7 billion euros with steel firm Danieli. During his meetings, Rouhani

invited Mattarella and Renzi to visit Iran. Rouhani also addressed a group of 500 Italian business leaders during his visit. On Jan. 27, 2016, Iran and Italy issued a joint statement outlining a

roadmap for bilateral cooperation.

Italy was Iran’s

largest European trade partner before sanctions were tightened in 2010. Sanctions forced Italy to cut bilateral trade to one fifth of its previous volume.

On Jan. 27, 2016, Rouhani arrived in France for meetings with French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius, President Francois Hollande, and a group of French business leaders. On Jan. 28, 2016, French and Iranian officials signed

20 agreements for economic, political, and cultural cooperation. French automaker Peugeot announced it had reached a deal with Iran Khodro worth

$436 million to manufacture

200,000 cars per year in Iran. Energy company

Total also reportedly signed a deal to buy up to 200,000 barrels of Iranian crude oil per day. And Airbus finalized a deal to deliver more than

100 commercial jets to Iran.

Rouhani was the first Iranian president to visit to France since

1999. Despite taking a

tough stance during the nuclear negotiations, France was among the first European countries to seek improved ties with Iran after the nuclear deal was signed in July 2015. Rouhani’s visit, however, prompted

protests from French human rights groups against executions in Iran.

Trendlines

- EU-Iran commercial ties are likely to expand following the lifting of sanctions as part of the implementation of the final nuclear deal.

- The EU is keen on encouraging Iran to play a constructive role in the Middle East, especially in Syria, and to engage with the Gulf states.

- Iran’s performance on human rights will be a key to EU actions. Further deterioration on rights issues could lead to additional EU travel bans against officials tied to abuses. The human rights issue could also increase the European parliament’s role in shaping the European debate on Iran policy.

Walter Posch is a senior research fellow working on Iranian domestic, foreign and security policy at the German International and Foreign Policy Institute in Berlin.

Garrett Nada, assistant editor of The Iran Primer, and Cameron Glenn, a senior program assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace, contributed to an update of this chapter in February 2016.

Photo credits: European Union map (cropped) by Kolja21 (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Rafsanjani via HashemiRafsanjani.ir; Khatami via Khamenei.ir; EU ministers in Iran by Mojtaba Salimi (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Ahmadinejad at Natanz via Iranian President's Office and The New York Times; EU+3 and Iranian officials via U.S. State Department; Rouhani with Mogherini and Hollande via President.ir

The EU played a crucial role in the new diplomacy between Iran and the world’s six major powers precipitated by the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani. EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton led the talks that resulted in the November 2013 interim nuclear agreement. And her successor, Federica Mogherini, chaired the talks that led to the July 2015 final deal.

The EU played a crucial role in the new diplomacy between Iran and the world’s six major powers precipitated by the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani. EU foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton led the talks that resulted in the November 2013 interim nuclear agreement. And her successor, Federica Mogherini, chaired the talks that led to the July 2015 final deal. After a decade of war and revolutionary turmoil, President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani began pushing Iran toward normalcy in both domestic and foreign policy when he was elected in 1989. Iran’s new tone, combined with its geopolitical and economic importance, convinced the European Union—as distinguished from individual member states—to consider intensifying relations. In 1992, the European Council made the formal decision to reach out to Iran. A host of issues still caused serious tensions, including Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa calling for the death of Salman Rushdie, author of “The Satanic Verses.” So the EU initiated a “critical dialogue,” rather than try to establish formal ties through a Trade and Cooperation Agreement or a Political Dialogue Agreement–as the EU would with other countries.

After a decade of war and revolutionary turmoil, President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani began pushing Iran toward normalcy in both domestic and foreign policy when he was elected in 1989. Iran’s new tone, combined with its geopolitical and economic importance, convinced the European Union—as distinguished from individual member states—to consider intensifying relations. In 1992, the European Council made the formal decision to reach out to Iran. A host of issues still caused serious tensions, including Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa calling for the death of Salman Rushdie, author of “The Satanic Verses.” So the EU initiated a “critical dialogue,” rather than try to establish formal ties through a Trade and Cooperation Agreement or a Political Dialogue Agreement–as the EU would with other countries. The surprise election of President Mohammad Khatami in 1997 changed the Iranian political climate at home and with the outside world. His new reform agenda made re-engagement possible. The EU decided to revamp the “critical dialogue” and launch a new “comprehensive dialogue.” Within this format, EU and Iranian officials met twice a year at the level of under-secretary of state. The range of issues was enhanced; human rights and non-proliferation issues were put higher on the agenda.

The surprise election of President Mohammad Khatami in 1997 changed the Iranian political climate at home and with the outside world. His new reform agenda made re-engagement possible. The EU decided to revamp the “critical dialogue” and launch a new “comprehensive dialogue.” Within this format, EU and Iranian officials met twice a year at the level of under-secretary of state. The range of issues was enhanced; human rights and non-proliferation issues were put higher on the agenda. In the autumn of 2003, the EU’s “Big Three”—Britain, France and Germany—launched an initiative to defuse the crisis created by Iran’s secret nuclear program. The three foreign ministers travelled to Tehran to convince the regime to take three pivotal steps: suspend uranium enrichment, detail the full scope of its nuclear program and facilities and sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Additional Protocol, which provided for more intrusive IAEA inspections. The European Council's secretary general and foreign policy chief, Javier Solana, joined the negotiating team. The EU-3 finalized the Paris Agreement with Iran on Nov. 15, 2004. The Paris Agreement was a major turning point proving the effectiveness of joint EU diplomacy. The EU-3 initiative became the EU's main modus operandi for transatlantic diplomacy with the United States, as well as nuclear diplomacy with Iran.

In the autumn of 2003, the EU’s “Big Three”—Britain, France and Germany—launched an initiative to defuse the crisis created by Iran’s secret nuclear program. The three foreign ministers travelled to Tehran to convince the regime to take three pivotal steps: suspend uranium enrichment, detail the full scope of its nuclear program and facilities and sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Additional Protocol, which provided for more intrusive IAEA inspections. The European Council's secretary general and foreign policy chief, Javier Solana, joined the negotiating team. The EU-3 finalized the Paris Agreement with Iran on Nov. 15, 2004. The Paris Agreement was a major turning point proving the effectiveness of joint EU diplomacy. The EU-3 initiative became the EU's main modus operandi for transatlantic diplomacy with the United States, as well as nuclear diplomacy with Iran. In early 2006, Iran was referred to the U.N. Security Council because of its failure to provide information on its past covert nuclear program. The EU continued to take the lead in trying to convince Tehran to cooperate with the international community. Solana, the EU foreign policy chief, became the sole negotiator with the Iranians. In 2006 and in 2008, Solana presented offers for a negotiated solution that included several economic and diplomatic incentives, in both cases backed by the United States and the U.N. Security Council. Tehran rejected both packages, even though the price was a new round of sanctions.

In early 2006, Iran was referred to the U.N. Security Council because of its failure to provide information on its past covert nuclear program. The EU continued to take the lead in trying to convince Tehran to cooperate with the international community. Solana, the EU foreign policy chief, became the sole negotiator with the Iranians. In 2006 and in 2008, Solana presented offers for a negotiated solution that included several economic and diplomatic incentives, in both cases backed by the United States and the U.N. Security Council. Tehran rejected both packages, even though the price was a new round of sanctions.

On July 28, 2015, EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini arrived in Tehran for a one-day visit with senior Iranian officials. Mogherini said the nuclear deal “has the capacity to pave the ground for wider cooperation between Iran and the West.”After meeting with Mogherini, Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that Iran and EU had agreed to hold talks “over different issues, including energy cooperation…human rights, confronting terrorism, and regional issues.”

On July 28, 2015, EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini arrived in Tehran for a one-day visit with senior Iranian officials. Mogherini said the nuclear deal “has the capacity to pave the ground for wider cooperation between Iran and the West.”After meeting with Mogherini, Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that Iran and EU had agreed to hold talks “over different issues, including energy cooperation…human rights, confronting terrorism, and regional issues.”