Since its 1979 revolution, Iran’s military ties with China have evolved through four phases. Tehran was dependent on Beijing as its primary source of weaponry during the eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s. It bought warplanes, tanks, and missiles. China welcomed the hard currency that, in turn, allowed it to develop new weapons systems. Arms transfers plummeted after the war ended in 1988. Iranian imports of major Chinese military equipment increased again between 1993 and 1996, but then petered out and have never recovered.

The nature of military ties started shifting to technology transfers in the 1990s. Iran began to reverse-engineer Chinese weaponry, including anti-ship cruise missiles. In the 21st century, Tehran increasingly claimed that it could produce many of its own arms, rockets, drones, and missiles. By April 2023, Iran’s conventional army was 90 percent self-sufficient in producing weapons, Rear Admiral Habibollah Sayyari boasted.

The relationship had instead shifted to joint military drills and broader strategic cooperation on maritime operations, piracy, counterterrorism, and search and rescue operations in the mid-2010s. Both countries sought deeper collaboration. In 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed an official 25-year strategic agreement, partly because of Beijing’s voracious appetite for imported oil to fuel its military and industries. It also wanted guarantees that the Islamic Republic would not support the restive Muslim population in western Xinjiang. Tehran and Beijing signed the agreement in 2021.

Iran has sought to engage both China and Russia as “equal strategic partners in a new multipolar word,” Farzin Nadimi, an Iran expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told The Iran Primer. Tehran’s progress with Beijing has been slower than with Moscow due to Iran’s increasing military self-reliance as well as China’s reticence to provide advanced technology to Iran. Iranians have also preferred other options, “and the Chinese know it, but circumstances bring them together.”

The relationship between the two major Asian governments—which both came to power in historic revolutions but have been ideological opposites—is still more of a marriage of convenience and largely transactional. Their common interests center largely around countering U.S. influence and the current international order. Their shared antipathy towards the Western-dominated global order, however, “is not the same thing as shared sympathies toward each other,” Dean Cheng, a China expert at the U.S. Institute of Peace, told The Iran Primer.

“These interests united the two countries after the Iranian revolution and led to deepened cooperation, particularly in the military arena,” Grant Rumley told The Iran Primer. “Today, however, I do not think China ranks its relationship with Iran as its most important in the region, as it may have at points in the past. On the other hand, I think Iran would rank China as one of its most important, if not the most important, relationship today.”

For Tehran, U.S. pressure—blocking arms sales, imposing sanctions on its military leadership, and refusing to provide parts for U.S. equipment purchased during the monarchy—has been its primary hurdle on multiple fronts for more than four decades. For Beijing, the U.S. pivot to Asia in the 21st century is viewed as an obstacle to increasing its influence around its own borders as well as globally.

Neither country has benefited significantly from the military relationship, Dawn Murphy, a China expert at the National Defense University, told The Iran Primer. “If one side gained more than the other, it was Iran,” although the ties were “not a significant enhancement to Iran,” she said.

Phase One: 1979 to 1988

The revolution and its messy aftermath complicated Iran’s ability to get arms from the Western countries that had supplied the shah. After the monarchy ended, Britain refused to transfer more than 1,300 tanks and 250 repair vehicles that had been paid for.

In April 1979, two months after the revolution, the new government canceled orders for U.S. fighter jets, naval destroyers, submarines, missiles and parts for existing military systems—worth billions of dollars—to signal its rejection of American influence. The takeover of the U.S. Embassy in November 1979 led the Carter administration to freeze all Iranian assets held in the United States, including the funds not yet returned to Tehran for the canceled orders.

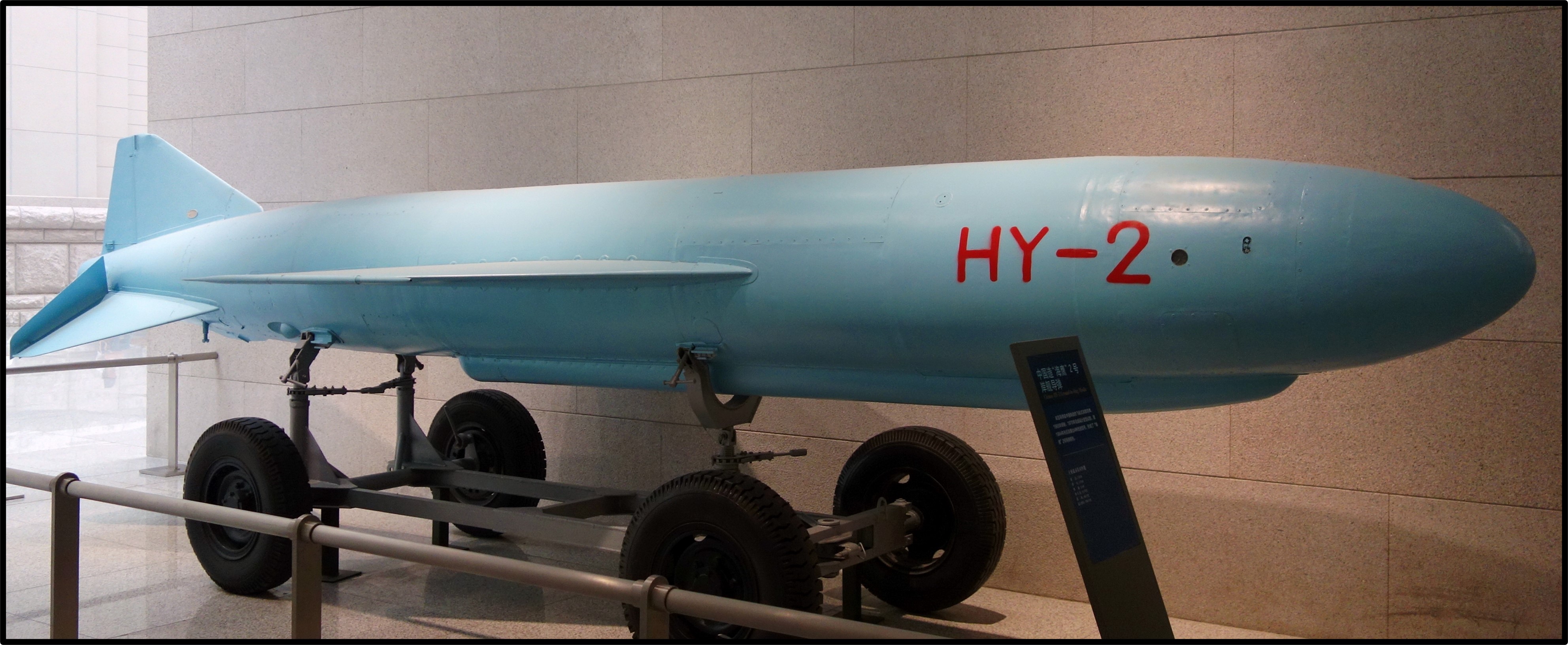

As a result, Iran was largely dependent on acquiring Chinese arms after Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s military invaded in 1980. The end of the hostage crisis, after 444 days, did little to help Iran resupply since most of the military equipment it bought during the monarchy was American. During the eight-year war, Iran imported warplanes, artillery and tanks including J-6 fighter aircraft, T-59 and T-69 tanks, and Silkworm antiship missiles from China, which also covertly provided some weaponry to Iran through North Korea.

During the war, Iran reportedly fired the Chinese Silkworms at U.S. ships as well as Kuwaiti ships and oil facilities. “These missiles can span the Strait [of Hormuz] at its narrowest point and represent for the first time a realistic Iranian capability to sink large oil tankers,” warned Assistant Secretary of State Richard Murphy in 1987. “Their presence gives Iran the ability both to intimidate the Gulf states and Gulf shipping and to cause a real or de facto closure of the Strait.”

In October 1987, the Reagan administration froze high-technology transfers to China to deter it from selling missiles to Iran. Chinese arms transfers to Iran peaked that year at $539 million. In March 1988, China reportedly told the State Department that it would not sell Silkworms to Iran. The United States lifted the freeze on technology exports to China, although Beijing did not stop the transfers to Iran.

China’s arms sales to Iran did not amount to a new alliance. Beijing exploited the war by selling to both countries. Over eight years, Iran imported nearly $2 billion worth of Chinese weapons, while Iraq purchased more than $4 billion, according the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

Phase Two: 1989 to 1996

Iran’s arms imports from China decreased significantly after a U.N.-brokered ceasefire in August 1988. Transfers briefly spiked again in the 1990s to $318 million—more than half the peak in 1987—as the Islamic Republic sought to rebuild its depleted military after the war. Its major acquisitions included dozens of fighter jets, hundreds of missiles and related technology, and naval military vessels.

Iran also used Chinese equipment and technology to advance domestic arms production. During the second phase, it began manufacturing weapons—notably missiles—based on Chinese models. In late 1996, China signed a military contract to transfer aircraft, warships, armored vehicles, missile and electronic technology, and military training to Iran. Despite the overall drop in sales, “Iran continued to be China's top recipient of conventional arms in the Middle East,” Murphy said.

Phase Three: 1997 to 2011

The 1996 Iran-China arms contract deal fell apart a year later, when Beijing limited missile and nuclear transfers to Tehran in order to improve relations with the United States. Iran’s weapons imports from China plunged to $52 million in 1997. Arms sales then fluctuated—between roughly $40 million to $80 million annually—for more than a decade. The third phase marked the end of the Islamic Republic’s major arms purchases from the People’s Republic.

In the early 21st century, Iran faced growing obstacles in both importing and exporting arms because of the advances in its nuclear program. In 2005, the International Atomic Energy Agency—the U.N. nuclear watchdog—declared that Iran had failed to comply with its obligations under the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty. In 2006, the U.N. Security Council, including China, unanimously passed Resolution 1737, which directed all U.N. member states to prevent the supply, sale or transfer of materials to Iran used in nuclear or ballistic missile programs. The resolution marked unusual agreement among the world’s rival powers.

Iran still balked at cooperating with the IAEA. In 2007, the U.N. Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1747. It prohibited member states from procuring combat equipment or weapons systems from Tehran and called on states to “exercise vigilance and restraint” in supplying such items to Iran. The U.N. measures limited but did not completely halt China’s military cooperation with Iran. In early 2010, Tehran unveiled a factory facilitated by Beijing to produce Nasr-1 anti-ship missiles, which were modeled on China’s C-704 missile.

In 2010, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad announced that Iran had enriched uranium to 20 percent—up from three percent. It was a major leap forward in Tehran’s ability to fuel a nuclear weapon. Brazil and Turkey proposed a fuel swap in which Iran would ship 1,200 kilograms of enriched uranium—about half its stockpile—to Turkey in exchange for fuel from France and Russia for the Tehran Research Reactor. The United States, France and Russia rejected the deal over concerns about the rest of Iran’s stockpile and its enrichment of uranium to 20 percent.

China and Russia were initially reluctant to support additional U.N. sanctions on Iran but ultimately voted for Security Council Resolution 1929 in mid-2010. It required all member states to prevent the supply of most major conventional arms and combat equipment—including battle tanks, armored combat vehicles, large caliber artillery systems, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missiles or missile systems and spare parts—to the Islamic Republic. It called on states to inspect vessels on their territory suspected of carrying prohibited items to Iran.

Phase Four: 2012-

During phase four, major arms transfers dropped to under $30 million in 2012 and sunk to zero in 2016. Military ties centered on more frequent joint exercises and visits. In 2013, the Iranian Navy sent a destroyer and a helicopter carrier to Zhangjiagang in China, a first for the Middle Eastern power. In 2014, China dispatched a destroyer and a frigate to Bandar Abbas for the first joint military drills carried out over five days in the Persian Gulf. Between 2014 and 2023, Iran and China participated in at least six bilateral or multilateral military drills.

Iran, Russia and China have started joint military drills today in the Indian Ocean. The military exercise has been dubbed "2022 Marine Security Belt." pic.twitter.com/PuVXQU4BQc

— Joe Truzman (@JoeTruzman) January 21, 2022

Chinese arms transfers to Iran virtually ceased after U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 2231 to endorse the 2015 nuclear deal and lift international sanctions. But the resolution still continued the ban on transferring conventional arms to Iran for five years or until the United Nations could verify that all of Iran’s nuclear material was for peaceful activities.

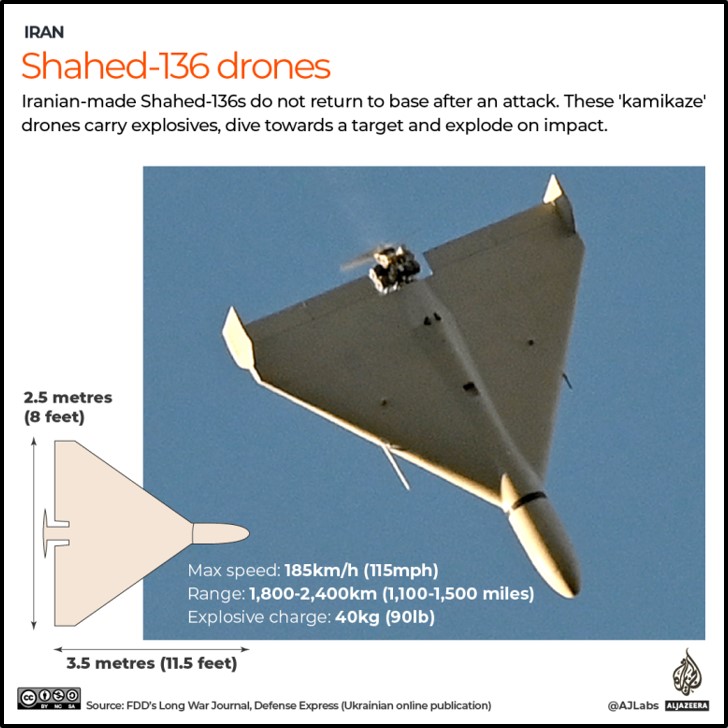

Iran was still able to acquire advanced technology from China for military use, however. In 2015, Tehran and Beijing signed a deal so that Iran could utilize China’s BeiDou 2 Navigation Satellite System, a rival to GPS that is useful for missiles and drones. The BeiDou2 became operational in 2020, and Iran got access to it in 2021. (The only other country with access is Pakistan).

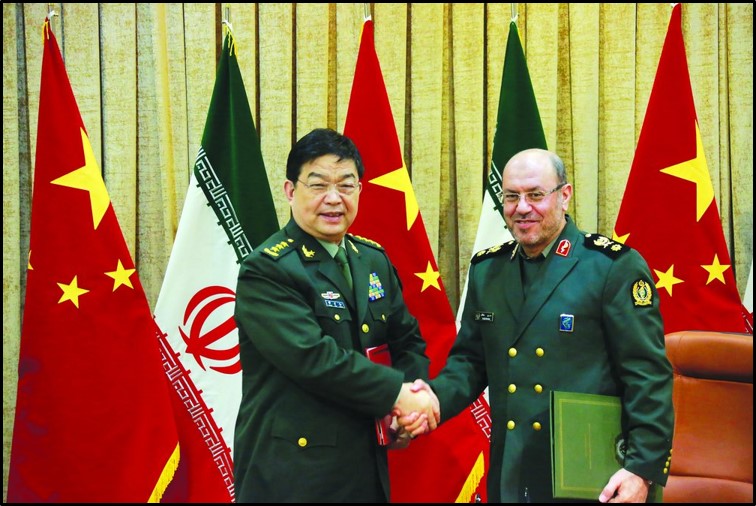

During phase four, political and military officials increased in-person visits to expand security cooperation. In 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and other top officials in Iran. The Iranian and Chinese defense ministers signed an agreement to strengthen military collaboration.

“Upgrading of relations and long-term defense-military cooperation with China is one of the main priorities of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s defense diplomacy,” Defense Minister Hossein Deghan said in Tehran. As part of the agreement, they set up a joint military commission. It met in Beijing in 2017 and in Tehran in 2019.

In 2020, the U.N. embargo on most arms transfers to and from Iran expired. Iran was then able to “procure any necessary arms and equipment from any source without any legal restrictions,” its foreign ministry said. But the government of President Hassan Rouhani vowed that “unconventional arms, weapons of mass destruction and a buying spree of conventional arms have no place” in its military strategy. Tehran did not import any major arms from China after the U.N. embargo expired.

The U.N. restriction on Iran’s import and export of missile-related technology, including missiles and drones with a range of 300 kilometers (186 miles) or more, remained in place. It was due to expire in 2023.

In 2021, the Iranian and Chinese foreign ministers signed a 25-year strategic agreement based on Xi’s proposal in 2016. The pact envisioned more cooperation on training and research, defense industries, military joint ventures like coproduction of fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, and strategic collaboration, Nadimi said. It also included exchange of experience on asymmetric warfare, anti-terrorism, and combating drug trafficking.

In 2023, Beijing continued to supply Tehran with parts for drones. The Russian military deployed hundreds of unmanned aircraft during its war in Ukraine. In April 2023, Ukraine downed an Iranian drone that contained a Chinese-manufactured navigational component. Tehran and Beijing also discussed the transfer of other technologies and materials for rocket and ballistic missile fuel.

As of mid-2023, however, Iran had not imported new weapons systems from China or started joint production of equipment as envisioned in the 2021 deal. Determining the level of research cooperation and what technology was transferred were difficult to quantify without published data from either country, Nadimi noted.

“What appears to be ongoing, then, is a range of broad discussions between Chinese and Iranian security establishments, some public cooperation, such as joint exercises, but an unclear degree of actual coordination or joint interoperation,” Cheng said.

Iran & China: Timeline of Military Ties

1980-1987: Iran bought approximately 100 Chinese J-6 fighters, which were modeled on the Soviet Union’s MiG-19. Iran deployed the J-6 during its eight-year war with Iraq.

1982-1984: Iran acquired 300 Chinese T-5 tanks, which were based on the Russian T-54 tank.

April 1983: A high level-Iranian military delegation visited Beijing and reportedly secured its first major arms deal with China for $1.3 billion. China committed to deliver J6 fighters and T59 tanks as well as artillery and light arms over three years.

March 1985: Iran reportedly signed a $1.6 billion deal with China to import 12 Chinese F-6 fighters, 200 T-59 tanks, antitank guns, and rocket launchers over two years.

1986: China reportedly supplied Iran with $1.6 billion in weapons including Chinese versions of MiG-21 fighters, 180 tanks and various kinds of missiles.

1986-1988: Iran acquired up to 500 Chinese T-69 tanks, which had upgraded armor and guns.

1986-1989: Iran acquired more than 100 Chinese HY-2 “Silkworm” anti-ship missiles, which were used extensively by both Iran and Iraq during the Gulf War in the 1980s.

1987-1998: Iran bought more than 300 Chinese C-801 anti-ship missiles, which were second-generation Chinese missiles.

March 1988: During a visit to the United States, Chinese Foreign Minister Wu Xuequian pledged to stop selling Silkworm missiles to Iran and to support a proposed U.N. arms embargo on Iran if “the overwhelming majority” of the Security Council approved. Wu’s pledge did not cover other types of cruise missiles and conventional weapons.

1990-1994: Iran received up to 200 Chinese M-7 short-range ballistic missiles, which have a range of around 150 kilometers (or 93 miles).

1991: Iran acquired 72 Chinese F-7 fighter planes, which were based on the Soviet MiG-21.

Mid-1990s: Iran received 10 Houdong missile boats, which the IRGC Navy later deployed as capital ships armed with anti-ship cruise missiles.

2004: Iran received 40 Chinese C-701 anti-ship missiles.

2010: Iran’s defense industry opened a factory producing the Nasr-1, an anti-ship missile based on the Chinese C-704 missile.

March 2013: Iranian warships, including a destroyer and a helicopter-carrier, made their first port visit to China at Zhangjiagang in Jiangsu.

May 2014: In his first trip to China, the Iranian Defense Minister Hossein Dehqan met with his Chinese counterpart, Chang Wanquan. They discussed strengthening military ties and improving personnel training cooperation, according to Iranian state media.

September 2014: Chinese warships visited Iran for the first time to hold five-day joint exercises near the southern port of Bandar Abbas. “The voyage of the Chinese army’s fleet of warships for the first time in the Persian Gulf waters is aimed at joint preparation of Iran and China for establishing peace, stability, tranquility and multilateral and mutual cooperation,” said Iranian Rear Admiral Hossein Azad.

October 2014: Rear Admiral Habibollah Sayyari visited Beijing to meet with Admiral Wu Shengli of the People’s Liberation Army Navy and Defense Minister Chang Wanquan. They signed an agreement to conduct further joint naval exercises.

October 2015: In Tehran, Iranian Defense Minister Hossein Deghan hosted Admiral Sun Jianguo, Deputy Chief of Staff of the People’s Liberation Army Navy to deepen cooperation and exchange views on mutual strategic concerns.

November 2015: Iranian Air Force Commander Brig. Gen. Hassan Shah Safi met with his Chinese counterpart, Gen. Ma Xiaotian, and Vice-Chairman of China’s Central Military Commission General Khoji Liang in Beijing to discuss bilateral ties. Shah Safi also visited defense industry factories and air bases.

January 2016: On his Middle East tour, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Iran to meet with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and other top officials. The two nations committed to a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” including enhanced consultations over the conflicts in Syria and Yemen.

November 2016: In Tehran, Iranian Defense Minister Hossein Deghan and Chinese Defense Minister Chang Wanquan signed an agreement to strengthen military collaboration on training, counterterrorism and joint military exercises. “Upgrading of relations and long-term defense-military cooperation with China is one of the main priorities of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s defense diplomacy,” Deghan said.

June 2017: Iran and China conducted joint naval maneuvers in the Persian Gulf that focused on deterring piracy and defending trade fleets.

December 2017: In Beijing, Brig. Gen. Ghadir Nezamipour, the deputy chief of staff of the Iranian Armed Forces, talked with Chinese Defense Minister Chang Wanquan about expanding military cooperation. The discussion marked the first meeting of the Iran-China Joint Military Commission. Nezamipour also met with Maj. Gen. Shao Yuanming, the Deputy Chief of the Joint Staff on China’s Central Military Commission.

July 2018: A delegation of senior Chinese military officers met with Iranian Army Ground Force Brig. Gen. Kiomars Heidari in Tehran and discussed promoting bilateral defense relations, according to Iranian state media.

September 2018: In Beijing, Amir Hatami, the Iranian defense minister, discussed implementation of earlier military agreements with Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe and other top military officials.

September 2019: Maj. Gen. Mohammad Bagheri, the Armed Forces Chief of Staff, made the highest level visit to China by an Iranian military official since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The trip strengthened bilateral defense cooperation.

December 2019: In Tehran, Maj. Gen. Shao Yuanming met Navy Commander Rear Adm. Hossein Khanzadi shortly before four-day naval drills by Iran, China, and Russia in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Oman. Their first joint naval exercise dubbed, “Maritime Security Belt,” coordinated a campaign to fight terrorists and pirates in the Indian Ocean. The exercise showed that “Iran cannot be isolated,” said Iran’s Rear Adm. Gholamreza Tahani. Iran’s conventional navy and the Revolutionary Guards participated in shooting exercises and practiced rescuing ships under attack or on fire. The exchanges marked the second meeting of the Iran-China Joint Military Commission.

September 2020: Iran was one of a dozen countries that participated in the six-day “Kavkaz 2020,” drill in southern Russia. It included 80,000 multilateral troops and observers, mostly from Russia, but also from Iran and China. The exercise simulated a terrorist incursion with responses by ground, sea, and air forces. Iran participated mainly in the naval operation.

January 2021: China agreed to allow Iran access to its BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, which would increase the accuracy of Iran’s missiles, according to Iran’s ambassador to Beijing Mohammad Keshavarz-Zadeh. “Tehran will work with Beijing to build a fifth-generation Internet infrastructure in Iran,” he said. The two countries had signed an agreement in 2015 to share access.

March 2021: The Iranian and Chinese foreign ministers signed a 25-year cooperation agreement that had been proposed by Xi Jinping in 2016 and detailed in 2020. The document vowed to strengthen military ties through joint training and exercises, joint research, and weapons development.

January 2022: China, Iran, and Russia conducted joint naval drills in the Indian Ocean to expand cooperation on maritime security and “create a maritime community with a common future,” said Mostafa Tajoldin, an Iranian military spokesman.

April 2022: In Tehran, Wei Fenghe, the Chinese minister of national defense, met Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Gen. Mohammad Reza Ashtinai to improve strategic defense cooperation.

March 2023: China, Iran, and Russia conducted joint naval drills in the Gulf of Oman to “deepen practical cooperation” between the three navies and “inject positive energy” into regional stability,” the Chinese defense ministry said.