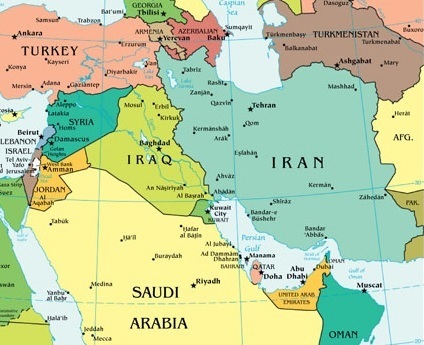

Relations between Iran and the Sunni sheikhdoms in the Gulf soured further in 2015. New Iranian outreach to the Gulf nations failed to stem the slide. In September, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries —Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates —

accused Iran of interference in their domestic affairs by harboring fugitives, supporting terrorist groups and inciting violence. Shiite Iran and its Sunni neighbors also supported rival actors in the Syrian and Yemeni conflicts. In a sporadic war of words, Tehran

accused Saudi Arabia of supporting terrorist groups, including

ISIS and al Qaeda. Riyadh accused Iran of sending thousands of militants to Syria, further fueling Shiite-Sunni tensions.

In Yemen, Iran supported the Houthis, a Zaydi Shiite movement that has controlled the capital, Sanaa, since September 2014. Tehran condemned Saudi Arabia after it launched an air campaign, with support from other Gulf states, against Houthi rebels in March 2015. In a reflection of the tensions, the IRGC commander

alleged in April that the kingdom was on the “edge of collapse” and that its air campaign was “shameless.”

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei called the Saudi intervention a “genocide.”

Riyadh countered that Iran was responsible for exacerbating the Yemeni conflict. “Iran has relations with the Houthis, as it provides them with weapons and specialists, and Iran is one of the main reasons behind the war in Yemen,” Foreign Minister Adel al Jubeir

said in October. In his address to the U.N. General Assembly, Jubeir said Riyadh wanted good relations with Tehran, but also called on it to stop interfering in Arab affairs.

Saudi-Iran tensions flared again in September when hundreds of pilgrims – including more than

400 Iranians – died in a

stampede during a Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia, home to Islam's two holiest cities.

Bahrain

Bahrain’s troubled relationship with Iran was a microcosm of tensions between the Gulf states and Tehran. Their relations have been troubled since predominantly Shiite Bahraini citizens protested the Sunni-dominated government and monarchy in 2011 during the Arab Spring. Manama has routinely accused Tehran of meddling in its domestic affairs. Iran has denied interfering, saying that it only generally supports opposition groups seeking greater rights for Shiites. In February, Bahrain’s interior ministry published a list of 72 individuals whose nationality had been

revoked over “intelligence, security, terrorism and allegiance issues.”

Bahrain

announced in July that it had foiled an arms smuggling plot by two of its citizens with ties to Iran. Citing hostile Iranian statements, Manama withdrew its ambassador from Tehran. Iran’s foreign ministry

urged Bahrain to deal with its own domestic issues and have a serious national dialogue instead of playing a “blame game.” In August, Bahraini authorities arrested five people for alleged links to Iran in connection with a

bombing that killed two policemen.

In October, Bahraini security forces reported they had found a large weapons cache including 1.5 tons of C4 explosives. Bahrain’s foreign affairs ministry

said it recalled its ambassador in Tehran “in light of continued Iranian meddling in the affairs of the kingdom of Bahrain ... in order to create sectarian strife and to impose hegemony and control.” The foreign ministry also gave Iran’s acting charge d’affaires three days to leave Bahrain.

In November, Bahrain arrested 47 members of a group allegedly tied to “terror elements in Iran.” A public prosecutor said five individuals had communicated with Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. They were

stripped of their citizenship and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Turkey

Iran’s relationship with Turkey in 2015 was characterized by both rivalry and cooperation. The biggest challenge facing the two was how to resolve the Syrian crisis. Ankara sought the removal of President Bashar al Assad while Tehran significantly upped its military presence in Syria to shore up his regime. Turkey also supported Saudi Arabia’s air campaign against the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Iran, widely seen as a backer of the Zaydi Shiite movement, condemned the intervention as a violation of Yemeni sovereignty.

In March, Turkish President Recep Erdogan accused Iran of trying to dominate the region and foment sectarianism. “Iran has to change its view. It has to withdraw any forces, whatever it has in Yemen, as well as Syria and Iraq and respect their territorial integrity,” he said at a press

conference. Several Iranian lawmakers

called on their government to cancel Erdogan’s April visit to Tehran, and one said Erdogan was trying to rebuild the Ottoman Empire.

Despite tensions, Erdogan made the trip. He and Rouhani signed eight agreements and focused on boosting economic cooperation. The two have been close trade partners for years. Iran accounts for some 20 percent of Turkey’s gas imports. A bilateral preferential trade agreement went into effect in January. Throughout 2015, the two sought ways to double their annual bilateral trade volume to $30 billion. Turkish Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek said the nuclear deal, announced in July, was “great news” for the Turkish economy and bilateral trade.

In December, the gulf between Turkey and Iran seemed to widen further. Erdogan again accused Iran and Iraq of pursuing sectarian policies in an

interview with Al Jazeera. He justified the presence of Turkish troops in northern Iraq by citing the local needs of Sunnis for arms and self-defense training. “What will happen to Sunnis? There are Sunni Arabs, Sunni Turkmen and Sunni Kurds? What will happen to their security? They need [a] sense of security,” said Erdogan. Turkey also

joined a 34-state coalition of solely Sunni states, led by Saudi Arabia, to fight terrorism. Shiite Iran’s exclusion from the group highlighted the deepening sectarian divide.

South and Central Asia

Iran had greater success strengthening ties with its eastern neighbors in 2015. India and Pakistan were among the first countries Zarif visited after the nuclear deal’s announcement in July.

India remained Iran’s top oil

buyer after China in 2015. As of October, it was India’s seventh largest

supplier. Before international sanctions severely curtailed Iran’s exports around 2010, it was India’s second largest supplier. “India has been a friend of Iran in difficult times, and we don’t forget that,” Zarif

told reporters in New Delhi in August. India moved to secure its interests in Iran’s natural gas reserves, the second-

largest in the world. In December, a consortium of Indian companies reached an initial agreement to

develop the Farzad B gas field under a $3 billion contract. Tehran and Delhi were also reportedly discussing a

plan to build a $4.5 billion undersea gas pipeline to connect southern Iran to western India.

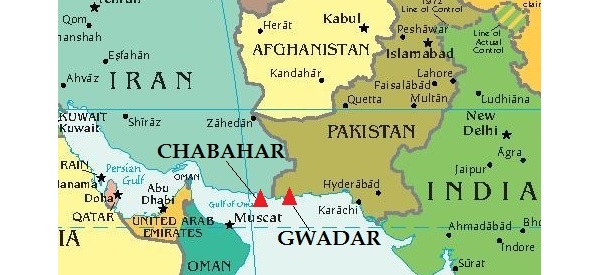

In an effort to increase bilateral trade of other goods, India and Iran signed a memorandum of understanding in May to develop the strategically important Chabahar port on Iran’s southern coast. In October, India said it was ready to invest some $196 million in Chabahar, but

stipulated that investments would depend on the price of Iran’s natural gas. India and Iran both aim to seal the deal by January. Just 44 miles west of Pakistan’s Gwadar port, Chabahar could help India expand trade ties into Central Asia. India would also be less dependent on land routes through Pakistan to Afghanistan.

India-Iran economic cooperation is likely to continue expanding in 2016, when both are

expected to become members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The intergovernmental group, founded in 2001, promotes cooperation among its six member states and six observer states in the political, economic, cultural, security and science spheres. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Rouhani actually met on the sidelines of a BRICS/SCO

summit in July.

Tehran was also keen on strengthening ties with Islamabad. Zarif visited Pakistan three times in 2015. In April, Zarif

discussed the Yemeni crisis and Iran-Pakistan border security with Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and other top officials. The shared 500-mile border runs through the homeland of the Baloch —a Sunni ethnic group that has waged a decades-long insurgency against both countries.

In August, Zarif met with Sharif in Islamabad again. Zarif

said they discussed ways to increase cooperation “in sectors ranging from oil to gas, energy, transportation and others.” Security cooperation was also high on the agenda again. Islamabad

assured Iran of its resolve to start work on its part of the gas pipeline. Iran completed its part of the $1.5 billion project in 2013, but Pakistan stalled due to international sanctions on Iran’s nuclear program.

In December, Zarif

visited Islamabad for the fifth Heart of Asia – Istanbul Process Ministerial Conference aimed at helping bolstering regional security and economic cooperation with a focus on Afghanistan. Representatives from 14 countries

participated.

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani visited Tehran in April. He and Rouhani

announced plans to enhance security cooperation to counter ISIS and drug smuggling. They

agreed to expand economic cooperation, especially regarding trade, transit, energy, industry and mining. Both countries had a shared interest in shoring up security along their porous 585-mile border. Smugglers have long taken advantage of the difficult terrain to sneak drugs into Iran. In 2015, however, Tehran became increasingly concerned about the possibility of a border attack by ISIS. In November, Iran conducted

exercises near the border to simulate one.

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP.

Photo credits: Syria talks by US Dept of State via Flickr Commons; Erdogan and Rouhani and Ghani and Rouhani via President.ir;

Tensions between the Islamic Republic and the Arab world deepened in 2015, exacerbated by the wars in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. President Hassan Rouhani’s top priority after securing the nuclear deal in July was to improve relations with Tehran’s neighbors. Iran made limited progress in upgrading ties with its neighbors in South and Central Asia. But overall, Shiite Iran instead was isolated, especially as Sunni nations increased cooperation among themselves.

Tensions between the Islamic Republic and the Arab world deepened in 2015, exacerbated by the wars in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. President Hassan Rouhani’s top priority after securing the nuclear deal in July was to improve relations with Tehran’s neighbors. Iran made limited progress in upgrading ties with its neighbors in South and Central Asia. But overall, Shiite Iran instead was isolated, especially as Sunni nations increased cooperation among themselves.

In March, Turkish President Recep Erdogan accused Iran of trying to dominate the region and foment sectarianism. “Iran has to change its view. It has to withdraw any forces, whatever it has in Yemen, as well as Syria and Iraq and respect their territorial integrity,” he said at a press conference. Several Iranian lawmakers called on their government to cancel Erdogan’s April visit to Tehran, and one said Erdogan was trying to rebuild the Ottoman Empire.

In March, Turkish President Recep Erdogan accused Iran of trying to dominate the region and foment sectarianism. “Iran has to change its view. It has to withdraw any forces, whatever it has in Yemen, as well as Syria and Iraq and respect their territorial integrity,” he said at a press conference. Several Iranian lawmakers called on their government to cancel Erdogan’s April visit to Tehran, and one said Erdogan was trying to rebuild the Ottoman Empire.