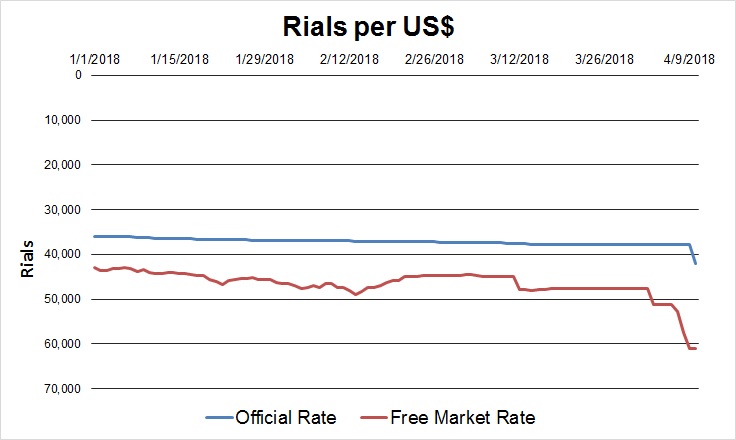

The value of Iran’s rial declined rapidly in early April, triggering a race on foreign currency and public panic. Iranians who lined up outside banks to buy dollars were turned away because of shortages. The rial had already been depreciating for months. It lost nearly half of its value on the free market against the dollar between September 2017 and April 2018. The trend accelerated in late March 2018.

In a major setback with potential political fallout, the rial lost 18 percent of its value on the free market between April 7 and April 9. It hit an all-time low against the dollar, which was reportedly being traded for 62,000 rials on the free market. The official rate – set by the Central Bank of Iran – was 37,830 rials.

Once #Iran's government has announced that a #USD will be exchanged with the single rate of 42,000 rials, people have gone to exchanges to buy USD, but there's no dollar with that rate & many exchanges don't sell #dollar. pic.twitter.com/M5KZcQxjZl

— Abas Aslani (@AbasAslani) April 10, 2018

The devaluation could set back Iran’s economy, which had only begun to recover from years of international sanctions. President Hassan Rouhani’s government has been trying to attract foreign investment, with limited success. Uncertainty over the future of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal has contributed to economic turmoil. The rial’s drop in value could give investors further pause.

Sources: Iran's Central Bank and Bonbast.com

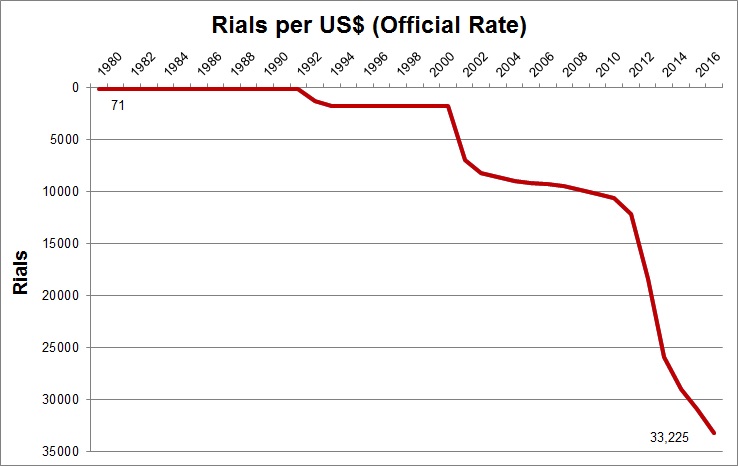

The current crisis is not the first for revolutionary Iran. Since 1979, Iran’s Central Bank has at times had multiple rates. By the end of the 1980-1988 war with Iraq, Iran had 12 different official rates for the U.S. dollar. The system favored select industries and imports to cope with declining foreign exchange reserves and economic turmoil caused by the war and the oil glut in the 1980s. President Hashemi Rafsanjani reduced the number of exchange rates to four in the 1990s. President Mohammad Khatami unified the official exchange rate in 2002. But Iran still had a free market rate not set by the Central Bank.

The official exchange rate has been used for state transactions, which allows the purchase of some imported goods, such as medicine, at favorable rates. Large transfers of foreign capital in and out of Iran have also been conducted at the official rate. In the private sector, smaller sums have been allowed to change hands at the market rate.

Source: Iran's Central Bank

The gap between the official and free market rates was relatively minimal until 2010, when the free market rate began to outpace the official rate. Due to subsequent shocks and failed interventions by the Central Bank, the differential between the two rates has been around 15 percent for the past decade.

The gap has encouraged speculation and corruption. Some officials have reportedly abused the formal exchange rate to purchase goods at rates not available to the private sector. The Rouhani government has tried to rein in corruption by curtailing the list of imported items available at the official rate. Valliollah Seif, the Central Bank governor, planned to unify the two rates by March 2017, but ran into obstacles.

Several factors contributed to the 2018 crisis, according to economist Bijan Khajehpour, including:

- Ambiguity about exchange rate policies

- Central Bank’s poor preparedness for a surging demand for hard currency

- Inability of the Central Bank to repatriate external funds

- Growing demand for gold and hard currency due to lack of attractive investment options

Anxiety over the future of the nuclear deal contributed to the slide. For more than two years, Iran did not reap full benefits of the accord, which dampened public confidence in the economy — and currency. Iran saw substantial economic growth in 2016, but mostly in sectors that were not labor intensive, such as the oil industry. Unemployment hovered around 12 percent in early 2018. The cost of living, meanwhile, has steadily increased. “The country’s economic strength is dwindling away and people feel it is risky to keep their rials,” a retiree standing in line to buy dollars said in April.

Iranians have grown increasingly pessimistic about economic conditions, according to polling by the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland and IranPoll.com.

In January 2018, about a third of survey respondents said that “foreign sanctions and pressures” had the most negative impact on the economy.

The psychology of sanctions has played a key role in the rial’s devaluation since at least 2012. After the United States announced new sanctions, Iranians moved to protect their wealth by buying gold, foreign currency and real estate, which contributed to a quicker slide in the rial’s value.Iranians took similar precautions in early 2018. In the first quarter, gold coin and bar demand in Iran hit a three-year high on “investor concerns over worsening Iranian-U.S. relations and the prospect of currency controls,” the World Gold Council said in report.

Government Response

In February 2018, the government froze speculators’ accounts, arrested foreign exchange dealers, and raised interest rates. But the rial’s value did not stabilize. On April 9, 2018, President Hassan Rouhani presided over an emergency meeting about the rial’s depreciation. The government decided to finally unify the free market exchange rate and the official exchange rate — at 42,000 rials to the dollar. Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri warned that anyone trading at a different rate would be violating the law and engaging in smuggling. “I assure the people that the government is capable of providing enough foreign exchange resources to the market,” Jahangiri said. “The government is determined to preserve the stability of the economy.”

But black-market currency trading has continued despite Jahangiri’s warning. In early May, the black-market rate hit 70,000 rials to the dollar compared to the new government-imposed rate of 42,000 rials to the dollar.

On April 10, 2018, Parliament grilled Central Bank Governor Seif, a technocrat who has faced allegations of mismanagement. Conservative Falahat Pishe accused Seif of betraying the country. Reformist lawmaker Rouhollah Babai called on the judiciary to try “those responsible for the country’s economic problems.” The Central Bank chief under the Shah was executed over similar tumult following the 1979 revolution, he recalled.

On April 16, Seif assured colleagues that the exchange rate would fluctuate only five to six percent per year — compared to the loss of 18 percent in three days the previous week — if his policies were implemented. But the next day, 163 of Parliament’s 290 members had signed onto a letter to President Rouhani calling for Seif’s dismissal.

"Iranians travel abroad more than normal, that should be balanced," said Iran’s central bank chief Seif as he desperately tries to control the foreign exchange market and the falling currency. Many MPs have asked for his resignation. pic.twitter.com/dvIF0XAwXK

— Bozorgmehr Sharafedin (@bozorgmehr) April 30, 2018

Iran has taken several steps to curb devaluation. In April, it set a limit on the amount of foreign currency an individual may hold at 10,000 euros. It also limited foreign currency purchases at Iranian airports to 500 euros per person for those traveling to “near countries,” and 1,000 euros for others going to “far countries.” Only banks at six Iranian airports, however, had foreign currency on hand to sell at the official rate. On April 18, local media announced that Iran would start reporting foreign currency amounts in Euros rather than dollars to reduce dependence on U.S. currency.

The rial’s devaluation began as an economic problem, then morphed into a political crisis as Parliament and the Rouhani government reacted. The issue has now moved into the judiciary. On April 23, Iranian media reported that the Central Bank had banned use of cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, in financial transactions to prevent money laundering and terrorism. Judiciary chief Sadegh Larijani pledged to assist the Central Bank. “The judiciary, police, and intelligence officers will cooperate with the Central Bank in order to stabilize the foreign currency market,” he said.

The Governor of Iran’s Central Bank Valiollah Seif says the government eyes replacing the US #dollar with the #euro in its international transactions and the idea has been welcomed by the Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. https://t.co/nYKnkoHMJS pic.twitter.com/8auyTgYaOZ

— Iran Front Page (@IranFrontPage) April 11, 2018

During a trip to Khorasan Razavi province, Rouhani assured citizens that the government was working on the currency issue. “Our priority in foreign currency is to supply people's basic needs,” he told local officials and business leaders.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of "The Iran Primer" and "The Islamists" websites at the U.S. Institute of Peace.