Nasser Hadian

What is Iran’s role in the region?

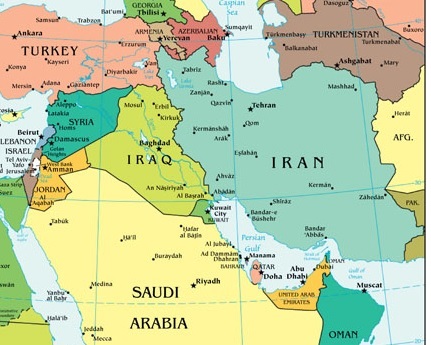

For at least the next 10 or 15 years, the orienting principle of Iran’s foreign policy should be stability. Instability in neighboring countries can create security problems for Iran, so the overarching objective is to act as a stabilizing force in the region. This possibly guides U.S. policy as well, since the United States would also like to see a more stable Middle East.

Look at what is happening in Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan. Saudi Arabia is in transition. Iran is getting frightened. Considering the multi-ethnic nature of Iranian society, no matter how strong the state is, there is a reason to be concerned. Instability in the region might have a trickle-down effect on Iran’s security. So stabilizing the region will be the main guiding principle of Iran’s foreign policy for the next several years.

Look at what is happening in Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan. Saudi Arabia is in transition. Iran is getting frightened. Considering the multi-ethnic nature of Iranian society, no matter how strong the state is, there is a reason to be concerned. Instability in the region might have a trickle-down effect on Iran’s security. So stabilizing the region will be the main guiding principle of Iran’s foreign policy for the next several years.Iran is not necessarily looking for Islamic governance in any country. Iran would prefer a country with a revolutionary Islamic government, challenging the U.S. and the world order. But Iran is also realistic enough to know that’s not always a possibility. Iran basically wants a non-ideological government, whether it has an Islamic tone as in Turkey or under [former President and Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed] Morsi in Egypt, or a secular regime like Bashar Assad.

What are the top foreign policy issues for Iran today?

The nuclear issue is number one. The next priority is Iraq, followed by Syria, Lebanon and Afghanistan, which are equal priorities. After that, Iran is worried about Pakistan.

Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Bahrain are not top priorities right now. Iran doesn’t feel the same urgency to deal with those issues.

What is Iran’s role in Iraq?

Iran’s view is that the territorial integrity of Iraq should be preserved, so Iran is helping the central government logistically, financially, and politically. That’s exactly what Iran did by helping the transition process from Prime Minister Maliki to Prime Minister Abadi. And there’s a famous saying that Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani called the Americans for help, and they didn’t come. They called the Turks, and they didn’t come. But when they called Iran, [Qods Force commander General] Qassem Soleimani was there eight hours later. The Qods Force and Revolutionary Guards are in Iraq in an advisory role, but they are not engaged in fighting.

Iran’s view is that the territorial integrity of Iraq should be preserved, so Iran is helping the central government logistically, financially, and politically. That’s exactly what Iran did by helping the transition process from Prime Minister Maliki to Prime Minister Abadi. And there’s a famous saying that Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani called the Americans for help, and they didn’t come. They called the Turks, and they didn’t come. But when they called Iran, [Qods Force commander General] Qassem Soleimani was there eight hours later. The Qods Force and Revolutionary Guards are in Iraq in an advisory role, but they are not engaged in fighting.Iran is also mobilizing Iraqi forces to fight ISIS. Iran is in contact with Sunni tribesmen to get their support for the central government. Iran also persuaded the Kurds to remain part of Iraq.

The Qods Forces are in close contact with a number of Iraqi militias. Those links are so strong that Iranian forces don’t need to fight in Iraq. For instance, the Badr Brigades brigades were organized in Iran. It’s not just up to Iran to order them around; they are very much within the Iranian power structure. They can influence and shape Iranian policy towards Iraq.

Where does Iran share interests with the United States?

Iran makes its policy decisions in Iraq independent of the United States. They can cooperate with one another on some issues. For instance, they have a shared interest in fighting ISIS, so they coordinate through the Iraqi government, but not directly with each other. Neither wants to create the impression among Sunnis that Shiites are cooperating with the West to suppress ISIS. So the United States and Iran are very careful to take a strong position against each other.

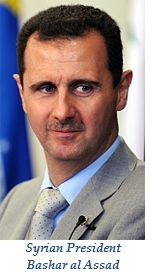

What is Iran doing in Syria, and to what extent is it wedded to the Assad regime?

One of Iran’s goals in Syria is reducing the power of the presidency. Iran is not committed to keeping Assad in power. It’s entirely feasible to see Assad stepping down when he finishes his term, if he can be persuaded to make a face-saving exit. But he would be allowed to finish his term, as a practical measure.

The sudden removal of Assad as a figurehead would mean there is a good chance the whole regime would collapse, which neither the United States nor Iran wants. It would make the situation even more chaotic. Finding a way for the regime to be preserved, but for Assad to leave, is one proposal Iran is considering. This could include reducing the power of the presidency, decentralizing power, and allowing the rational opposition to participate in government. Realistically, there are only two options: ISIS or Assad. It is wishful thinking that the Free Syrian Army could succeed, so adopting these measures is more practical and would help isolate and defeat ISIS.

The sudden removal of Assad as a figurehead would mean there is a good chance the whole regime would collapse, which neither the United States nor Iran wants. It would make the situation even more chaotic. Finding a way for the regime to be preserved, but for Assad to leave, is one proposal Iran is considering. This could include reducing the power of the presidency, decentralizing power, and allowing the rational opposition to participate in government. Realistically, there are only two options: ISIS or Assad. It is wishful thinking that the Free Syrian Army could succeed, so adopting these measures is more practical and would help isolate and defeat ISIS.The four key regional and international players – Iran, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States – have to deal with the issue. If the Saudis are reluctant, they could be replaced by the Turks. If they agree on a plan, Iran and Russia are in a position to persuade Assad to accept it, and the United States and Saudi Arabia are in a position to gain cooperation from the Free Syrian Army.

In Yemen, the Houthis have emerged over the last 6 months as a dominant player. They now control the capital. What is Iran doing in Yemen? What does Iran want to see happen?

I cannot imagine that Iran is not involved in Yemen, especially since the Houthis seized power so quickly. But it’s probably not to the extent that the West believes. Iran is probably advising the Houthis militarily, likely through the Qods force. But Iran’s plate is already full dealing with Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Iran cannot play a very active role in Yemen. And the Houthis actually don’t need that much help. They are probably receiving money, but not arms – they are already well armed. The point is that they have their own grievances, their own organization, and their own reasons to rebel. So Iran is probably not spending that many resources in Yemen.

Iran is not concerned about who is in power in Yemen as long as the government has a good, friendly relationship with Iran. Iran is not necessarily looking for an Islamic government or a Houthi government – it realizes the Houthis are a minority.

The rise of the Houthis is more an indication of the failure of Saudi Arabia’s influence than the success of Iran’s policy. Yemen and Saudi Arabia are linked to one another, and the Saudis have channeled a lot of resources to Yemen.

Iran does not consider Saudi Arabia a threat, but the Saudis felt threatened by Iran even under the shah. Since the revolution, they have taken all sorts of measures to contain Iran’s influence. They are spending money in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, principally to counter Iran. The formation of the Gulf Cooperation Council was part of that as well. They want to contain Iran and limit its resources. For the Saudis, the cost of that action is what’s going on in Yemen.

Tension has defined relations with Saudi Arabia for some time. What does Iran want from Saudi Arabia?

Iran wants a normal relationship with Saudi Arabia, and it wants a Saudi government that is not against Iran in principle. It does not want Saudi Arabia to challenge Iran economically, politically, and militarily. Take Syria, for example. Iran supports Assad and Hezbollah as a way of deterring Israeli attacks against Iran. It’s not about the Saudis.

But why do the Saudis want Assad removed from power? It’s not because Saudi Arabia is democratic and Assad’s regime is not. It’s about reducing Iran’s influence. They want Assad to step down because he has a good relationship with Iran. Iran is not challenging the Saudis, but they are challenging Iran.

What does Iran want in Lebanon?

Iran would like to see a friendly and working government there, but it doesn’t matter if the government is being controlled by Sunnis, Christians, or Hezbollah – as long as Hezbollah remains a strong military force to deter Israeli attacks.

Iran has two modes of defense against Israel. One is conventional missiles, which are not very precise. The other is Hezbollah. So Hezbollah’s rockets and missiles have a far more reliable deterrent capability than Iran’s own missiles. If you want to see Iran support a different Hezbollah, or a different Syria, the Israeli threat has to be reduced. In the beginning, after the revolution, Iran’s relationship with Hezbollah was ideological. But now it is more pragmatic.

Iran has two modes of defense against Israel. One is conventional missiles, which are not very precise. The other is Hezbollah. So Hezbollah’s rockets and missiles have a far more reliable deterrent capability than Iran’s own missiles. If you want to see Iran support a different Hezbollah, or a different Syria, the Israeli threat has to be reduced. In the beginning, after the revolution, Iran’s relationship with Hezbollah was ideological. But now it is more pragmatic.Iran does not want to see another confrontation between Israel and Hezbollah – it would be crazy to want that. Hezbollah’s position within Lebanese society would be jeopardized if it was perceived as fighting a proxy war. Iran is spending a lot of money there, not just for military purposes, but also for building infrastructure, schools, and roads. These efforts have been perceived positively by Christians, and even a small minority of Sunnis. Many of them have their own grievances against Israel. Thus Iranian support of Hezbollah has been welcomed by many in Lebanese society.

An Iranian general was recently killed on the Golan Heights – what was he doing there? What does Iran want from Israel?

The general was helping the Syrians, but that does not include attacks on Israel. Iran has basically been building infrastructure against the Israelis for deterrence. But Iranians and Israelis have both been very careful not to directly engage one another. The confrontation began only a few years ago with the killing of Iranian scientists. The Iranians attempted to retaliate in a very unwise and unsophisticated way in operations abroad. They were an indication that Iran never thought that Israel was going to take direct action against Iran. That’s why they were not prepared.

There is not a unified Iranian view in terms of what to do about Israel. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has proposed a referendum [among both Israelis and Palestinians] on the Palestinian issue. But former President Mohammad Khatami proposed de facto acceptance of two-state solution. There is actually not that much debate going on in Iran about what to do in Israel. There is so much urgent discussion about other issues that Israel is not as much of a priority as it once was.

What does Iran want in Bahrain?

What Iran wants is not necessarily a democratic Bahrain, but a fair government that respects the rights of Shiites and gives them more participation in the political process. It’s not about regime change. If Bahrain improves its treatment of Shiites, relations with Iran could improve.

It was very humiliating for Iran when the Saudis sent forces into Bahrain. The Bahraini government claimed that Iran was involved there, but it was not – so Iran was made the scapegoat. Iran engaged in the propaganda war very late, after the Saudis and Bahrainis, who took a strong position against Iran.

Iran is about to celebrate its 36th anniversary of the revolution. How is Iran’s foreign policy different than it used to be?

In the beginning, Iran’s view of the world was idealist, and in action it was principlist. As time passed, Iran became more realist. Iran was idealist throughout the hostage crisis, but in the end acted pragmatically. In the war with Iraq, Iran was still idealist and acted with principlist tendencies. But by the end of war, Iran was realist – no longer idealist. And Iran acted pragmatically to end it.

So in terms of foreign policy, Iran was idealist and acted principlist, and as time passed, Iran became realist in its views and then acted pragmatically. The trajectory of both has been moving from idealism and principlism to realism and pragmatism.

Nasser Hadian is a professor of political science at the University of Tehran.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

Photo credits: Leader.ir, Syria-Iran by RonenY [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons, Bashar al Assad by Fabio Rodrigues Pozzebom / ABr [CC BY 3.0 br (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/br/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons