By Robin Wright

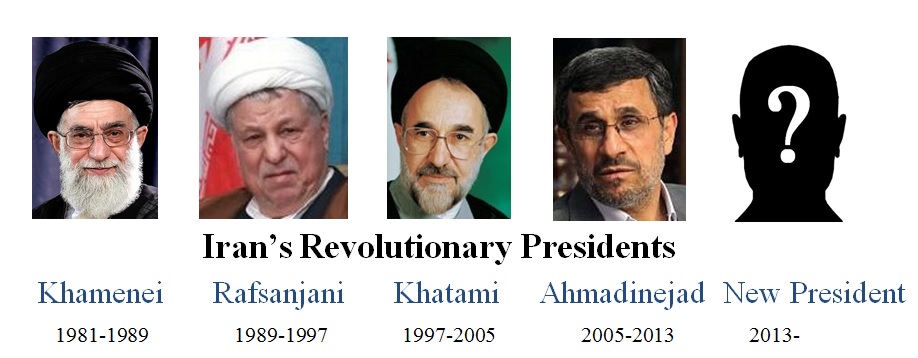

The field of candidates may be limited, but the outside world can still learn a lot from Iran’s 2013 presidential poll. The election will provide three pivotal metrics about the Islamic republic now that the Ahmadinejad era is ending.

First, the (real) turnout at the polls will indicate how many Iranians still have an interest in the world’s only modern theocracy. The government is quite obsessed with the number of people who vote to prove it still has a public mandate. Voting has become almost an existential issue for the ruling clerics.

First, the (real) turnout at the polls will indicate how many Iranians still have an interest in the world’s only modern theocracy. The government is quite obsessed with the number of people who vote to prove it still has a public mandate. Voting has become almost an existential issue for the ruling clerics. “A vote for any of these eight candidates is a vote for the Islamic Republic and a vote of confidence in the system and our electoral process,” Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said in a public appeal on June 4. He charged that the outside world was plotting to ensure a low turnout. Leaders clearly hope at least 60 percent of the estimated 50 million voters will turn out.

Second, reaction to the results will signal whether the public deems the election process itself legitimate. It’s no small issue. Many Iranians believed the 2009 presidential poll was fraught with fraud—and that Ahmadinejad was not really reelected. The reaction sparked the greatest challenge to the Iranian regime since the 1979 revolution. It gave birth to a new opposition movement.

Over the next eight months, millions turned out in cities across Iran to challenge the results—and to demand “Where is my vote?” The regime used brutal force, arrested thousands, and held Stalinesque trials to quash the new Green Movement opposition.

In 2013, the regime has already witnessed signs of discontent even before the vote. On June 4, thousands reportedly turned the funeral for Ayatollah Jalaluddin Taheri into an anti-government demonstration in Isfahan. Taheri had been the Friday Prayer Leader in Isfahan. He had earlier criticized the regime for corruption, eventually resigning from the post. He also called the 2009 election “invalid.”

At his funeral, supporters chanted “death to the dictator,” a reference to the supreme leader and a rallying cry from 2009. Others shouted “Free Mousavi and Karroubi,” the two reformist presidential candidates in 2009 and co-leaders of the Green Movement. They have been under house arrest for more than two years.

Again, the regime has publicly conceded its concern about the day-after-the-vote. On June 4, the supreme leader charged that unnamed foreign powers were plotting to foment “sedition” after the poll.

Third, the new president—if the election is credible—may indicate who is capturing the public imagination. Iranians surprised the outside world—and themselves—in electing dark horses in both 1997 and 2005. The regime favorites were trounced in both polls.

In a stunning upset, the 1997 election brought to power Mohammad Khatami, a purged former culture minister who was director of the national library. The vote marked the beginning of the reform era.

In 2005, the final runoff was defined as a battle between “the turban and the hat” – or a cleric against a layman. Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a former president, ran against little- known Tehran Mayor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

For the first time since the revolution’s early days, a cleric did not win. The vote was widely interpreted as public rejection of the clerical monopoly of power—more than as overwhelming support for Ahmadinejad, an engineer and specialist in traffic management.

Because of past controversies and regime paranoia, the list of candidates in 2013 offers little variety—arguably less than in any election since the revolution. Even former President Rafsanjani was disqualified from running—along with more than 670 other candidates.

But the eight candidates, all ardent supporters of the revolution and Islamic rule, don’t have cookie cutter views. The televised debates have even had flashes of disagreements over the economy, censorship, academic freedom, and women’s rights.

The election will also be telling about the key to Iran’s future–its disproportionately large young population. Because the Islamic regime aggressively encouraged larger families in the 1980s, its population almost doubled from 34 million to 62 million in a decade. Today, about two-thirds of Iran’s 75 million people are under age 35. Even more striking, about half of voters are reportedly under 35.

The young also face the widest array of challenges in Iranian society, from inadequate access to higher education and serious housing shortages to increasing unemployment or underemployment. All three are pivotal to independence and marriage. Frustrations among the young have been reflected in several growing social problems, from narcotics to prostitution.

The big issue for the regime, however, is the level of political engagement. Half of Iran’s electorate was born after the revolution. They have no memory of the monarchy—or the factors that inflamed passions behind the revolution. Since youth played a huge part in the 2009 protests, their interest in voting, their choices at the polls, and their reaction to the results could also be disproportionately important—and potentially decisive.

In the end, Iran’s president may not have real executive power. Khamenei—ironically himself a former president—still dominates the policy process. Iran’s supreme leader has a virtual veto over almost everything.

Yet the president does matter in Iran. His administration strongly influences the tone of politics, the economy and the cultural atmospherics—as well as many appointments.

Khatami allowed the flowering of an independent press, fewer restrictions on women, and wider cultural expression in the arts. He talked about bringing down the “wall of distrust” with the outside world and introduced the idea of a dialogue among civilizations at the United Nations. He also brought many other reformers with their own ideas about ways to open up Iran into top jobs.

In contrast, Ahmadinejad brought into power many from his days in the Revolutionary Guards during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. His closest aide was an in-law through the marriage of his children. Both men framed policy considerations in terms of the return of the missing 12th imam, whom many Shiites believe went into “occultation” or hiding in 941 AD and whose reemergence would bring peace and justice to the world.

So this vote will count. Despite the huge array of restrictions on the election, Iranians will be able to signal a lot about what they’re thinking at a particularly important juncture in Tehran’s relations with the outside world.

Robin Wright has traveled to Iran dozens of times since 1973. She has covered several elections, including the 2009 presidential vote. She is the author of several books on Iran, including “The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and transformation in Iran” and “The Iran Primer: Power, Politics and US Policy.” She is a joint scholar at USIP and the Woodrow Wilson Center. See her chapter, “The Challenge of Iran” from "The Iran Primer."

This piece is published in collaboration with Foreign Policy.