Kelsey Davenport is the Director for Nonproliferation Policy at the Arms Control Association.

After the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the father of Iran's nuclear program, Parliament passed a new law in December 2020 requiring the government to accelerate its nuclear program. What are the key points? How much progress has Iran made on each?

The law triggered a serious escalation in Iran’s violations of the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The legislation mandates the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran to undertake several steps—including ramping up uranium enrichment—that pose a greater proliferation risk than Iran’s previous breaches. The activities may only be halted if Iran receives relief from certain sanctions.

Former President Hassan Rouhani blamed the law for impeding his administration’s ability to negotiate a mutual return to compliance by Iran and the United States with the JCPOA. On July 14, 2021, during his last month in office, Rouhani said that the deal could have been restored as early as March, had it not been for the escalatory nuclear steps required by the law.

By September 2021, the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran had met several of the law’s requirements, including:

- Enriching to 20 percent uranium-235,

- Installing and enriching uranium with 1,000 advanced IR-2 centrifuges,

- Installing equipment to produce uranium metal, and

- Reducing compliance with the JCPOA’s monitoring provisions by suspending the additional protocol to Iran’s safeguard agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and other verification measures specific to the nuclear deal.

Several provisions of the law must be met before the end of 2021, including:

- Stockpiling 120 kilograms of uranium enriched to 20 percent, and

- Installing and operating 1,000 IR-6 centrifuges.

As of Nov. 6, 2021, Iran’s stockpile of uranium enriched to 20 percent was 114 kilograms, according to the IAEA. If Iran’s production and accumulation of uranium enriched to this level continues at a similar rate, it will exceed the law’s 120-kilogram requirement by the end of the year. It is unclear if Iran will meet the IR-6 requirement, as its installation of those centrifuges has slowed, perhaps due to attacks targeting centrifuge production facilities. As of November 17, Iran had installed just over 400 IR-6 machines, of which about half were operating.

What do these advances mean for Iran’s breakout time? How have Iran's capabilities changed in the five years since the implementation of the nuclear deal in January 2016?

When Iran was fully implementing its JCPOA commitments, its breakout time—or the time needed to enrich enough uranium to make one nuclear bomb—was about 12 months. The provisions of the deal would have kept the 12-month breakout timeline in place for more than decade. That breakout calculation uses a standard assessment of how much highly enriched uranium is needed for a bomb: 25 kilograms of uranium enriched to above 90 percent.

Iran’s enrichment and stockpiling of uranium above 3.67 percent, as well as use of additional IR-1 centrifuges and more advanced centrifuges, cut its breakout time significantly. As of November 2021, breakout had dropped to about one month. It will narrow further if Iran meets the December 2021 deadline for IR-6 centrifuge installation and continues to grow its stockpiles of uranium enriched to 20 and 60 percent.

Iran’s enrichment and stockpiling of uranium above 3.67 percent, as well as use of additional IR-1 centrifuges and more advanced centrifuges, cut its breakout time significantly. As of November 2021, breakout had dropped to about one month. It will narrow further if Iran meets the December 2021 deadline for IR-6 centrifuge installation and continues to grow its stockpiles of uranium enriched to 20 and 60 percent.

If Iran were to return to compliance with the JCPOA quickly, the 12-month timeline could be restored by blending down or shipping out uranium in excess of the deal’s cap of 300 kilograms of uranium enriched to 3.67 percent. Tehran would also need to dismantle or destroy excess centrifuge machines.

The longer Iran continues to violate the deal, however, the more knowledge it gains about enrichment to higher levels and how to improve the performance of its advanced centrifuges. The irreversibility of this knowledge makes restoring the 12-month breakout period difficult without significantly altering the JCPOA’s terms.

U.S. and European officials have warned that further advances to Iran’s nuclear program may complicate a return by all parties to the JCPOA. “I’m not going to put a date on it, but we are getting closer to the point at which a strict return to compliance with the JCPOA does not reproduce the benefits that that agreement achieved,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said on September 8. “As Iran continues to make advances in its nuclear program, including spinning more sophisticated centrifuges, enriching more material, learning more, there is a point at which it would be very difficult to regain all of the benefits of the JCPOA.”

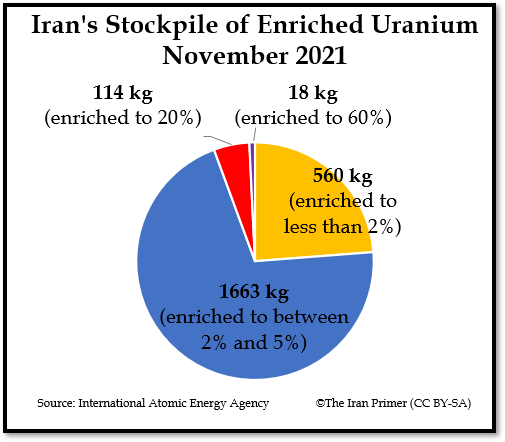

How large is Iran’s current stockpile of enriched uranium and what is its composition?

The JCPOA capped Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium at 300 kilograms of uranium gas enriched to 3.67 percent, which is the equivalent of 200 kilograms of uranium by weight. As of November 2021, Iran had accumulated 2,313 kilograms of enriched uranium. Iran's stockpiles of enriched uranium gas consisted of the following:

- 560 kilograms enriched to less than 2 percent,

- 1,633 kilograms enriched between 2 percent and 5 percent,

- 114 kilograms enriched to 20 percent, and

- 18 kilograms enriched to 60 percent.

In May 2019, Iran announced it would no longer abide by the enriched uranium stockpile cap. It further breached the JCPOAs limits on enrichment in July 2019, when it started enriching uranium to 4.5 percent. From a proliferation perspective, this initial increase beyond the 3.67 percent limit had little significance. Uranium enriched to less than 5 percent is generally considered appropriate for reactors but far below weapons grade.

In May 2019, Iran announced it would no longer abide by the enriched uranium stockpile cap. It further breached the JCPOAs limits on enrichment in July 2019, when it started enriching uranium to 4.5 percent. From a proliferation perspective, this initial increase beyond the 3.67 percent limit had little significance. Uranium enriched to less than 5 percent is generally considered appropriate for reactors but far below weapons grade.

In January 2021, however, Iran began enriching uranium to 20 percent, in accordance with the 2020 law. Iran had enriched to this level prior to the negotiations that led to the JCPOA. Enriching to 20 percent constitutes about 90 percent of the work necessary to get to weapons grade, but the material is still not suitable for a bomb.

Uranium enriched to 20 percent is often used in research reactors, and Iran has justified this higher level of enrichment by saying it will use the material to fuel the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). The TRR runs on 20 percent uranium fuel and produces medical isotopes. The JCPOA requires the world’s six major powers – Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States – to assist Iran in obtaining fuel for the TRR. But when the Trump administration reimposed U.S. sanctions, Iran was prevented from importing it.

In April 2021, Iran further accelerated its nuclear program in response to the sabotage of its main uranium enrichment facility, Natanz. It began enriching uranium to 60 percent, the highest level of enrichment Tehran has publicly acknowledged. It justified the move by saying that the uranium produced would be used for nuclear propulsion in ships or submarines, which is permitted in peaceful programs under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty to which Iran is a signatory. Iran, however, does not appear to be pursuing a nuclear propulsion program seriously. With large enough quantities, Iran could use uranium enriched to 60 percent for a nuclear weapon, but the device would be large and inefficient.

More importantly, enriching to 20 percent and 60 percent decreases the time it would take for Iran to pursue weapons grade uranium, because Iran can use the higher levels of enriched uranium as feed. How quickly would depend on the quantities of enriched uranium and the number and type of centrifuges being used.

What additional steps would Iran need to take if it decided to produce a nuclear weapon?

If Iran made the political decision to pursue nuclear weapons, Western and Israeli intelligence estimates assess that it would need about two years to build a bomb. After producing enough fissile material for a weapon, Iran would need to convert the material to metal and fabricate it into the core of a device. The uranium metal would then need to be fitted with an explosive package. If Iran planned to deliver its nuclear weapons via ballistic missile, which is the most likely scenario, it would have to fit the warhead to the tip of that system.

Since 2007, the U.S. intelligence community has assessed that Iran has the necessary capabilities to build a nuclear weapon, but the country has never tested a nuclear device. And Iran has repeatedly said that it does not intend to build one. If Tehran, however, wanted a reliable deterrent, it would likely want to first test a nuclear device. That would further extend the timeframe.

The E3 (France, Germany and Britain) and the United States have raised concerns about Iran’s production of uranium metal and highlighted its relevance to nuclear weapons development. But as of fall 2021, Iran had not resumed key activities to build a nuclear weapon. In an interview published on October 1, Israel’s head of military intelligence, Major General Tamir Hayman, said that he saw “no progress” on a weapons project and that Iran would need two years to build a nuclear weapon. Iran’s enrichment of uranium to higher levels is “disturbing,” but it is “not heading toward a bomb right now,” he added.

Which advances are reversible, and which are not?

Most of Iran’s violations of the nuclear deal are quickly and easily reversible. Iran could immediately halt enrichment to levels above 3.67 percent, quickly blend down to natural levels or ship out its excess stockpiles of enriched uranium. It could store, dismantle, or destroy centrifuges installed and operating in excess of the JCPOA’s limits.

Iran would also need to halt enrichment at the Fordo facility and remove any uranium and IR-6 centrifuges. The JCPOA bans uranium enrichment at the underground site until 2031. Fordo is only to be used for producing isotopes for medical purposes.

To return to the monitoring provisions, Iran would need to notify the IAEA that it was resuming implementation of its additional protocol and other JCPOA-specific monitoring mechanisms. Iran would likely also need to remove production equipment installed for its uranium metal activities, as the JCPOA prohibits uranium metal production until 2031.

These steps could be accomplished quite quickly, probably in less than three months. But Iran has gained knowledge from its violations that won’t be forgotten. In the past two years, Iran has produced uranium enriched to 60 percent, a new high, and gained experience operating and producing advanced centrifuges. This knowledge would be beneficial if Iran were to choose to pursue nuclear weapons in the future and would speed its ability to do so. Iran is also gaining experience with uranium metal production, a process it did not appear to have mastered in earlier experiments.

Restoring the IAEA’s continuity of knowledge about Iran’s nuclear activities may be difficult due to Tehran’s suspension of more intrusive verification activities since February 2021. While Iran allowed surveillance cameras to remain at key facilities and promised to turn over the data collected to the IAEA if the JCPOA is restored, there are already known gaps in coverage.

Tehran claimed that cameras were damaged at Karaj, one of its centrifuge production sites, in an attack in June 2021. As of November 17, Iran had prevented the IAEA from reinstalling cameras on three occasions. Iran argues that the facility, located outside Tehran, is not covered by an agreement reached on September 12 that allowed the IAEA to access and service other remote monitoring systems. The IAEA argues that the facility was included in the arrangement.

The loss of footage may compromise the IAEA’s ability to reconstitute a record of Iran’s activities during the period of reduced monitoring and complicate efforts to resume JCPOA verification activities. The monitoring program in Iran is “no longer intact,” Rafael Grossi, the IAEA chief, warned on October 22.

These gaps, and others that may emerge when the IAEA reviews the data, will probably drive speculation that Iran engaged in illicit activities and could make it more difficult for the IAEA to conclude that Iran’s nuclear activities are exclusively peaceful. “I would say we are flying in a heavily clouded sky,” Grossi told The Associated Press in November 2021. “We can continue in this way, but not for too long.”

How dangerous is the research and development that Iran has conducted? What would the implications be if the nuclear deal fell apart for a second time?

The long-term proliferation risk posed by Iran’s research and development will depend in part on how long such efforts continue and if Tehran is pursuing these actions to gain leverage or to master the capabilities. As of fall 2021, the risk is manageable and the nonproliferation benefits of restoring the JCPOA outweigh the irreversible knowledge that Iran has gained.

Iran has gained significant knowledge about centrifuge operation, performance, and production for certain models of advanced machines. As such, Tehran could ratchet up its enrichment program more quickly than it could prior to the JCPOA being breached. That risk can be managed if the JCPOA is restored by thinking creatively about how to deal with advanced centrifuge machines and other limits on Iran’s uranium enrichment program.

Continued work on advanced centrifuges and other sensitive areas of research and development, such as uranium metal research and production and 60 percent enrichment, may alter assessments on how Iran might produce nuclear weapons and the speed at which it could do so, if such a decision were made. As Iran masters these capabilities, its nuclear program will pose more serious proliferation risk, and the nonproliferation benefits of the JCPOA will be compromised.