Robin Wright

When Mohammed Javad Zarif left the United Nations in 2007, I asked what he had achieved in five years as Tehran's ambassador. "Not much," he said with a sigh. "A stupid idealist who has not achieved anything in his diplomatic life after giving one-sided concessions--this is what I'm called in Iran." He flew home depressed, faded into academia and vowed not to return to diplomacy.

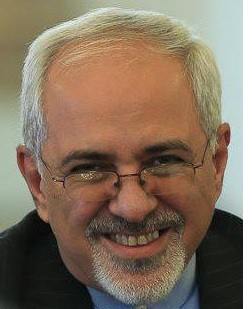

Over the past two months, however, Zarif has re-emerged to lead Tehran's boldest overture to the West since the 1979 revolution. Iran's charismatic new President Hassan Rouhani clearly commissioned the initiative, but his new Foreign Minister is the plan's architect.

It's the comeback of a diplomatic lifetime. "A second chance," Zarif told me last month. And a huge risk. If he fails to make a deal limiting Tehran's nuclear capabilities--on Oct. 15, Zarif sat down in Geneva with the world's six major powers for a fresh round of negotiations--Iran could face punishing military strikes.

It's the comeback of a diplomatic lifetime. "A second chance," Zarif told me last month. And a huge risk. If he fails to make a deal limiting Tehran's nuclear capabilities--on Oct. 15, Zarif sat down in Geneva with the world's six major powers for a fresh round of negotiations--Iran could face punishing military strikes. The talks went well, Zarif and top E.U. diplomat Catherine Ashton agreed. The negotiators will reconvene on Nov. 7.

Skeptics claim Zarif is merely buying time with all this talking so Tehran can work on developing nuclear weapons. "We know that deception is part of the [Iranian] DNA," State Department Under Secretary Wendy Sherman, chief U.S. negotiator in Geneva, warned a Senate committee on Oct. 3.

But Zarif has also built a following in Washington. "He doesn't play games," says Senate Select Committee on Intelligence chair Dianne Feinstein, who met Zarif in 2006 and was among a number of members of Congress who talked to him at the U.N. in September. "I think a deal is doable."

Zarif has the ear of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and was approached by three of the six candidates in June's presidential election to be their prospective Foreign Minister. But he has also been lauded by the likes of Democrat Joe Biden and Republican Chuck Hagel when they were in the Senate. And he earned a University of Denver doctorate under the same professors who taught Condoleezza Rice.

Zarif is not just the man of the moment, however. He helped create the moment by being at the heart of virtually every key deal Tehran struck with the U.S. for two decades, beginning in the late 1980s. He was the "invaluable" liaison in talks that freed dozens of foreign hostages seized by pro-Iranian militias in Lebanon in the 1980s, former U.N. official and hostage negotiator Giandomenico Picco says. And after the 2001 U.S. intervention in Afghanistan, U.S. diplomats credited the Iranian envoy with persuading the Afghan opposition to accept the U.S. formula for a new government in Kabul.

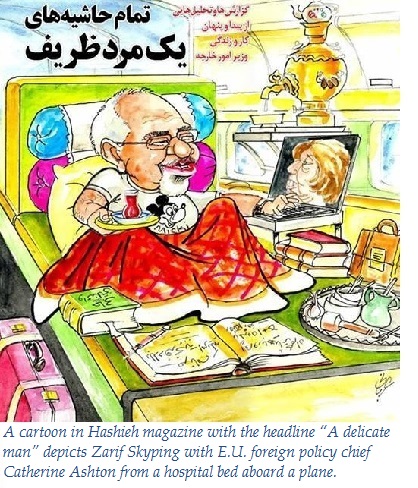

The danger--to Zarif and to the chances of a deal--may be that Zarif actually has too many American contacts. He was fiercely grilled by hard-liners during his parliamentary confirmation. Just days before the Geneva talks, a conservative newspaper claimed Zarif had deemed "inappropriate" the phone call between Presidents Obama and Rouhani at the end of the U.N. General Assembly. Zarif said he'd been misquoted, but the stress triggered nervous spasms that sent him to the hospital. Winning over the powerful hard-liners in Iran's complex power structure will continue to pose a huge challenge to Zarif--and Rouhani.

The real question," says Ryan Crocker, a veteran of U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East who has dealt with Zarif since 2003, "is whether hard-liners in both Tehran and Washington sabotage whatever comes out of this effort to resolve the nuclear issue and improve U.S.-Iran relations."

A host of issues will divide the two nations for years to come. But for the first time in 34 years, Zarif's frenetic diplomacy has spurred talk of détente between Tehran and Washington. When asked in New York City last month about the potential shape of future ties between Iran and the U.S., Zarif invoked the relationship between the U.S. and Russia, in which deep differences remain but communication and occasional collaboration continue nonetheless. It's a model far preferable to the military alternative. "This time," Zarif told me, "I can't afford to fail."

A host of issues will divide the two nations for years to come. But for the first time in 34 years, Zarif's frenetic diplomacy has spurred talk of détente between Tehran and Washington. When asked in New York City last month about the potential shape of future ties between Iran and the U.S., Zarif invoked the relationship between the U.S. and Russia, in which deep differences remain but communication and occasional collaboration continue nonetheless. It's a model far preferable to the military alternative. "This time," Zarif told me, "I can't afford to fail."This article is reposted from Time magazine.

Robin Wright has traveled to Iran dozens of times since 1973. She has covered several elections, including the 2009 presidential vote. She is the author of several books on Iran, including "The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and transformation in Iran" and "The Iran Primer: Power, Politics and US Policy." She is a joint scholar at USIP and the Woodrow Wilson Center.