Iran’s leaders are currently grappling with three key questions that are directly relevant to European interests.

- The first of these questions concerns how to rescue the economy and the role the West can and should play in this.

- The second centres on whether Tehran should engage in any form of diplomacy with Washington, especially after the assassination of Soleimani.

- The third focuses on whether Iran can protect its interests in the region primarily through diplomatic tools, or whether this requires a more offensive military approach. European governments that wish to persuade Iran to engage in a diplomatic process will need to absorb the lessons of internal debate on these issues.

Other Parts of the Report:

Regional Security

Iran’s leadership has faced numerous challenges in the Middle East in recent decades, including the war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, ongoing threats of US military assaults from bases hosted by its Arab neighbours, and ISIS attacks. Iranians have watched the Middle East become ever more turbulent, while neighbouring Iraq and Afghanistan have struggled to stabilise since the US military interventions there in the early 2000s. To their base, Iran’s leaders present themselves as protectors of the country against strikes by the US and Israel, and of Iran’s largely Shia population from Sunni extremist groups. Iran has an extensive missile programme that its leaders justify as a predominantly defensive measure following the experience in the Iran-Iraq war. Iran has also deployed the so-called ‘forward-defence’ narrative of taking the fight to enemies beyond Iran’s borders to explain the IRGC’s involvement in conflicts such as Syria’s and its support for Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The US maximum pressure campaign and the growing ties between Iran’s regional foes, such as Saudi Arabia and Israel, strengthen the consensus among Iran’s political camps that a united front is needed to reduce external threats. While preferences and tactics differ, all camps have gravitated towards a similar strategic agenda: to reduce the US military presence in the region, contain threats posed by Sunni extremist groups, deter US and Israeli attacks, and prevent a unified anti-Iran front from forming in the Arab world. To pursue these goals, the modernisers lean towards diplomacy and deal-making, while the securocrats and hardline Principlists favour military means.

The US maximum pressure campaign and the growing ties between Iran’s regional foes, such as Saudi Arabia and Israel, strengthen the consensus among Iran’s political camps that a united front is needed to reduce external threats. While preferences and tactics differ, all camps have gravitated towards a similar strategic agenda: to reduce the US military presence in the region, contain threats posed by Sunni extremist groups, deter US and Israeli attacks, and prevent a unified anti-Iran front from forming in the Arab world. To pursue these goals, the modernisers lean towards diplomacy and deal-making, while the securocrats and hardline Principlists favour military means.

Outreach to Neighbors

In recent years, the modernisers have focused on advancing these core objectives primarily through diplomatic outreach with Iraq and members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). This includes the Kuwaiti-facilitated shuttle diplomacy between Iran and Saudi Arabia in 2016-2017; [Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad] Zarif’s suggestion last year to establish a new regional security framework based on the UN resolution that ended the Iran-Iraq war; and Rouhani’s 2019 proposal for the “Hormuz Peace Endeavour”. These initiatives have failed to create a meaningful political opening for Iran with Riyadh. This is in part due to US opposition and the impasse with Saudi Arabia’s crown price Mohammad bin Salman – both maintain that there is little point in engaging with Iran’s modernisers given that the IRGC wreaks havoc in the region and is intent on exporting the Islamic revolution.

The modernisers have thus been unable to demonstrate that diplomacy can solve Iran’s problems with its Arab neighbours. Prior to Trump becoming president, the modernisers similarly argued that the best way to avoid a military confrontation with the US or Israel was to reach a political understanding with Washington on nuclear matters. However, the evolution of the White House’s Iran policy showed that the JCPOA has not removed the shadow of war. In fact, in the past year, military attacks against Iranian forces have increased, with Israel claiming to have successfully targeted IRGC positions in Syria, and the US delivering a blow to Iran with Soleimani’s assassination.

Hard Power

Dominant “IRGC-rule” voices among the securocrats argue for Iran to use hard power to advance its regional goals. They argue that direct and calculated attacks on Iran’s enemies will deter greater conflict. Since the start of the US maximum pressure campaign, the IRGC has repeatedly warned that “if any of the Arab countries in our region commits a misstep and launches aggression upon us, our missiles will hit all their military bases.” Iran stands accused by the US of planning and carrying out direct attacks on oil tankers and Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil facility in 2019. In a report issued in June, the UN allegedly concluded that weapons used to carry out the Aramco attack were of “Iranian origin”.

Despite the reputational damage for Iran, securocrats may feel justified in their choice of strategy given that these attacks seem to have successfully moderated the posture of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi by exposing the reluctance of the US to fight on their behalf. To some securocrats, such tactics arguably also pave the way for regional diplomacy. Since the series of attacks in 2019, Saudi and Emirati officials have been careful not to provoke Tehran. The United Arab Emirates has opened up its political and security channels with Iran and helped transfer humanitarian aid during the peak of covid-19. Saudi Arabia has also engaged in several track II initiatives aimed at cooling tensions with Iran.

Support for Militias

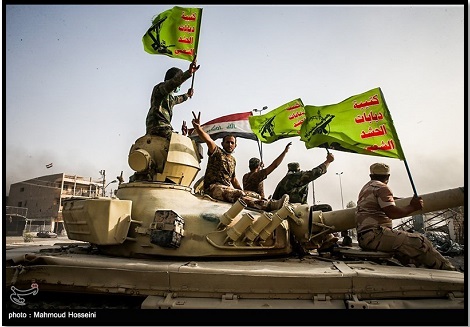

In contrast to modernisers’ distinct preference for engaging with state actors in order to make diplomatic progress, the Quds Force has established close ties with militia groups abroad to conduct asymmetric warfare against Iran’s enemies. The IRGC has mastered the art of stepping into conflict zones such as Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen to mobilise local groups there. This has provided deterrence against Iran’s enemies, such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, directly on their borders.

Since 2014, when ISIS began its advance in Iraq, the Quds Force has become more open about its ties to militia groups. After Iran’s attack on American forces in Ain al-Asad base, a senior IRGC commander gave a press briefing with flags of multiple militia groups behind him, stating that the decision to attack was “made following a full consensus reached among our officials and resistance groups”. During major flooding in 2019, and more recently the covid-19 outbreak, IRGC-linked media outlets provided extensive coverage of efforts by militia groups such as the Fatemiyoun brigade (comprised largely of Afghan recruits deployed in the Syrian war) and Iraqi Hashd al-Shaabi, which visited Iran to help with relief efforts. The securocrats have used national crises to demonstrate that their regional investments were paying off at home.

Some modernisers privately express frustration with the IRGC’s support for militia networks that they believe burden Iran with financial and reputational costs. But there is scant indication that the modernisers are pushing back heavily on this issue. Indeed, Iran’s foreign ministry also engages with Hezbollah, the Popular Mobilisation Forces in Iraq, and on at least one occasion arranged a meeting between the Houthis and European diplomats in Tehran.

The modernisers have pushed back harder against the IRGC on the issue of whether Iran should transform its asymmetric warfare with Israel and the US into a conventional contest. Iran would be at a disadvantage in such a conflict, especially when such activity increases the chances of miscalculation. This was shown with the downing of the Ukraine airliner and the recent death of 19 naval officers during military exercises. However, hardline securocrats are more comfortable with open conflict. As one media outlet affiliated with the IRGC commented, Iran’s recent missile attack on US forces in Iraq “vaccinated the Islamic Republic against any foreign military aggression”.

Ballistic Missiles

Iran’s missiles programme is a core issue. As a consequence of international sanctions, Iran’s access to conventional weapons is highly restricted and its air force is underdeveloped – which leads most of the ruling elite to view missiles as a minimum component of national defence. Iranian officials have repeatedly noted that the current range of Iran’s missiles is 2,000 kilometres. And, according to Western officials, Iran has one of the most advanced missile systems in the Middle East. Zarif has been a vocal defender of maintaining the programme; during Rouhani’s term, Iran has carried out missile attacks against ISIS in Syria, Kurdish separatists in Iraq, a US military drone, and Ain Al-Asad base. Iran has also been accused by its adversaries of transferring missile technology and equipment to Hezbollah in Lebanon and to actors in Iraq, while the UN reportedly found that missiles launched by Houthis against Saudi Arabia in 2017 share design features with those manufactured in Iran.

During and shortly after the nuclear talks, debate grew between Iran’s various power centres over the development of the missiles programme and its interaction with the diplomatic track. In 2014, Rouhani sparked controversy with the Principlists and the securocrats when he said that Iran’s power came not just from the “range of its missiles and military weapons”, pointing to the country’s economic efforts as being of equal significance. Similarly, soon after the nuclear deal was concluded, Rafsanjani caused uproar among the securocrats and the Paydari group when he tweeted that “the future world is the world of discourse, not missiles”. In a challenge to Rafsanjani’s comment, one media outlet close to the supreme leader’s office declared that “the future world is indeed the world of more explicit and open confrontations between good and evil.” This split reappeared in presidential campaign debates in 2017, when Rouhani alleged that the IRGC printed an “Israel must be wiped out” slogan on a missile during test launches “to sabotage the JCPOA”.

Iran’s supreme leader has a clear stance on the issue. He has drawn a direct connection between missiles and security. And he has hailed Iran’s missiles as a source of strength, consistently praising their accuracy and range. Khamenei has also called for Iran’s missiles to be upgraded and has repeatedly ruled out negotiations over the missiles issues, warning in November 2019 that, had Iran entered into such talks, the US would have first sought to restrict the range of the missile programme and then stopped it altogether.

The US maximum pressure stance and growing military escalation in the region has made Iran’s leader more reliant on missiles. Last year, Rouhani openly praised the downing of an American drone, adding that the missiles used in the attack were produced by the ministry of defence during his presidency. Following Soleimani’s killing, a senior Iranian lawmaker from the Reformist camp reflected that Iran was in no mood to negotiate over its missiles, warning: “I advise the European sides not to push us to [such a point that] we will have to resume work on [long-range missiles].”

Iran’s regional posture and its missiles programme fits into the Iranian leadership’s conception of the military balance of power, almost regardless of faction. So long as GCC countries and Israel continue to be leading purchasers of sophisticated arms and military technology, and the US maintains an active military presence on Iran’s borders, it will be extremely difficult for the West to secure significant concessions from Iran on the regional front and its missiles programme. However, Iran has already shown that it can play a useful role in the Yemen peace talks through its influence with the Houthis. It may be willing to take some steps to rein in its regional activities and its affiliates if this is connected to the withdrawal of US forces from neighbouring Iraq and Afghanistan, and from Syria.

Iran’s modernisers have also dangled the offer of high-level diplomacy with its Arab neighbours on several occasions – something that they would only have done with Khamenei’s backing. While the securocrats have adopted a militarised approach to the region, there is precedent for them accepting regional settlement agreed to by the supreme leader. The start of a diplomatic process between Iran and GCC countries could, in the long term, result in a framework that provides security guarantees to all players in the Middle East, including Iran.

This is an excerpt from a report first published by the European Council on Foreign Relations. Click here for the full text.

Ellie Geranmayeh is a senior policy fellow and deputy head of the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Photo Credit: Zarif by Bundesministerium für Europa, Integration und Äusseres (CC BY 2.0); Emad missile by Tasnim News Agency (CC BY 4.0)