Iran’s practice of imprisoning foreign nationals, including Americans, has been a recurrent flashpoint since the seizure of the U.S. Embassy and 66 hostages after the 1979 revolution. Between 1979 and 2023, Iran detained nearly 100 Americans, including several U.S.-Iranian nationals. The Americans included diplomats, businessmen, environmentalists, journalists, and academics, among others. The Islamic Republic has also detained dozens of foreigners, mainly from the West, including Britain, France, Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and Poland.

Freeing Americans, including dual nationals, has historically been complicated since Washington cut off relations with Tehran in 1980 during the initial hostage crisis, so negotiations have often had to be conducted through other countries. For decades, the Swiss Embassy in Tehran has hosted a U.S. Interest Section to provide Americans with limited consular services. But many dual nationals went to Iran on their Iranian passports, and the Islamic republic does not recognize dual citizenship—or their right to Swiss consular services or U.S. intervention. “Iranian authorities routinely delay consular access to detained U.S. nationals and consistently deny consular access to dual U.S.-Iranian nationals,” the State Department warned in a travel advisory in July 2023. Dual nationals have been charged with various crimes, including espionage and cooperating with an enemy power.

Over the decades, both Republican and Democratic administrations have cited Iran’s intelligence organizations--particularly the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Intelligence Organization--with detaining foreigners. At least four administrations participated in rounds of behind-the-scenes diplomacy and imposed layers of sanctions to pressure Tehran.

Three major prisoner exchanges

The Obama, Trump and Biden administrations have exchanged prisoners in deals that included financial terms:

- January 2016: The Obama administration released seven Iranians in exchange for four Iranian-Americans – Jason Rezaian, Amir Hekmati, Saeed Abedini, and Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari – held by Iran. The United States also returned $400 million (plus $1.3 billion in interest) that the former monarchy had paid Washington to purchase American military equipment. The arms transfer and funds were frozen by the Carter administration after the takeover of the U.S. Embassy. The prisoner exchange in 2016 coincided with the implementation of the Iran nuclear deal and settled Tehran’s longstanding claim to the funds.

- December 2019: The Trump administration exchanged Massoud Soleimani, an Iranian national held in an Atlanta prison for allegedly violating U.S. sanctions, for Xiyue Wang, a Princeton student conducting research for his doctoral dissertation.

- September 2023: The Biden administration freed five Iranians imprisoned in the United States in exchange for five Americans—Siamak Namazi, Emad Shargi, Morad Tahbaz, one unnamed businessman and one unnamed former U.N. employee. All five had been imprisoned on unproven charges of espionage or collaboration with an enemy state. Namazi, the longest held, had been imprisoned since 2015. The United States also issued a waiver so South Korea could transfer $6 billion of frozen Iranian oil revenues to Qatar, which will oversee limited Iranian purchases of humanitarian goods. The U.S. Treasury will also have oversight of the expenditures.

Timeline of 30 hostage crises with Iran since 1979

U.S. Embassy takeover (1979 - 1981)

Students belonging to the Students Following the Imam’s Line seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on Nov. 4, 1979. They were protesting the Carter administration’s decision to allow the deposed shah into the United States for cancer treatment. The students held 66 Americans hostage. Thirteen women and African-Americans were released in November 1979, and one man was released in July 1980 due to illness. The Iranian student leaders said that they intended to hold the embassy for a few days, but 52 Americans – including the Chargé d’Affaires, junior staff, and Marine guards – ended up being held for 444 days.

They American hostages included:

- Thomas L. Ahern, Jr., 48, McLean, VA. Narcotics control officer

- Clair Cortland Barnes, 35, Falls Church, VA. Communications specialist

- William E. Belk, 44, West Columbia, SC. Communications and records officer

- Robert O. Blucker, 54, North Little Rock, AR. Economics officer specializing in oil

- Donald J. Cooke, 26, Memphis, TN. Vice consul

- William J. Daugherty, 33, Tulsa, OK. Third secretary of U.S. mission

- Lt. Cmdr. Robert Englemann, 34, Hurst, TX. Naval attaché

- Sgt. William Gallegos, 22, Pueblo, CO. Marine guard

- Bruce W. German, 44, Rockville, MD. Budget officer

- Duane L. Gillette, 24, Columbia, PA. Navy communications and intelligence specialist

- Alan B. Golancinksi, 30, Silver Spring, MD. Security officer

- John E. Graves, 53, Reston, VA. Public affairs officer

- Joseph M. Hall, 32, Elyria, OH. Military attaché with warrant officer rank

- Sgt. Kevin J. Hermening, 21, Oak Creek, WI. Marine guard

- Sgt. 1st Class Donald R. Hohman, 38, Frankfurt, West Germany. Army medic

- Col. Leland J. Holland, 53, Laurel, MD. Military attaché

- Michael Howland, 34, Alexandria, VA. Security aide, one of three held in Iranian Foreign Ministry

- Charles A. Jones, Jr., 40, Communications specialist and teletype operator. Only African-American hostage not released in November 1979

- Malcolm Kalp, 42, Fairfax, VA. Position unknown

- Moorhead C. Kennedy Jr., 50, Washington, DC. Economic and commercial officer

- William F. Keough, Jr., 50, Brookline, MA. Superintendent of American School in Islamabad, Pakistan, visiting Tehran at time of embassy seizure

- Cpl. Steven W. Kirtley, 22, Little Rock, AR. Marine guard

- Kathryn L. Koob, 42, Fairfax, VA. Embassy cultural officer; one of two women hostages

- Frederick Lee Kupke, 34, Francesville, IN. Communications officer and electronics specialist

- L. Bruce Laingen, 58, Bethesda, MD. Chargé d’affaires. One of three held in Iranian Foreign Ministry

- Steven Lauterbach, 29, North Dayton, OH. Administrative officer

- Gary E. Lee, 37, Falls Church, VA. Administrative officer

- Sgt. Paul Edward Lewis, 23, Homer, IL. Marine guard

- John W. Limbert, Jr., 37, Washington, DC. Political officer

- Sgt. James M. Lopez, 22, Globe, AZ. Marine guard

- Sgt. John D. McKeel, Jr., 27, Balch Springs, TX. Marine guard

- Michael J. Metrinko, 34, Olyphant, PA. Political officer

- Jerry J. Miele, 42, Mt. Pleasant, PA. Communications officer

- Staff Sgt. Michael E. Moeller, 31, Quantico, VA. Head of Marine guard unit

- Bert C. Moore, 45, Mount Vernon, OH. Counselor for administration

- Richard H. Morefield, 51, San Diego, CA. U.S. Consul General in Tehran

- Capt. Paul M. Needham, Jr., 30, Bellevue, NE. Air Force logistics staff officer

- Robert C. Ode, 65, Sun City, AZ. Retired Foreign Service officer on temporary duty in Tehran

- Sgt. Gregory A. Persinger, 23, Seaford, DE. Marine guard

- Jerry Plotkin, 45, Sherman Oaks, CA. Private businessman visiting Tehran

- MSgt. Regis Ragan, 38, Johnstown, PA. Army noncom, assigned to defense attaché‘s officer

- Lt. Col. David M. Roeder, 41, Alexandria, VA. Deputy Air Force attaché

- Barry M. Rosen, 36, Brooklyn, NY. Press attaché

- William B. Royer, Jr., 49, Houston, TX. Assistant director of Iran-American Society

- Col. Thomas E. Schaefer, 50, Tacoma, WA. Air Force attaché

- Col. Charles W. Scott, 48, Stone Mountain, GA. Army officer, military attaché

- Cmdr. Donald A. Sharer, 40, Chesapeake, VA. Naval air attaché

- Sgt. Rodney V. (Rocky) Sickmann, 22, Krakow, MO. Marine Guard

- Staff Sgt. Joseph Subic, Jr., 23, Redford Township, MI. Military policeman (Army) on defense attaché‘s staff

- Elizabeth Ann Swift, 40, Washington, DC. Chief of embassy’s political section; one of two women hostages

- Victor L. Tomseth, 39, Springfield, OR. Senior political officer; one of three held in Iranian Foreign Ministry

- Phillip R. Ward, 40, Culpeper, VA. Administrative officer

The Algiers Accord ended the hostage crisis on Jan. 19, 1981. The United States agreed to release frozen Iranian assets and not to intervene in Iranian affairs. A court was established in The Hague to adjudicate lawsuits and property claims. In a snub to President Carter, Iran did not free the hostages until after President Ronald Reagan was inaugurated on Jan. 20, 1981.

Erwin David Rabhan (October 1984 - September 1990)

Erwin David Rabhan, an American businessman, was detained in October 1984 on suspicions of spying for the CIA. He had moved to Iran for business in 1976. Rahban, a friend and pilot of former President Jimmy Carter, was indicted in the United States in 1978 for federal securities violations. He was released by Iran in September 1990 and returned to the United States.

Jon Pattis (June 1986 - October 1991)

Jon Pattis, an American telecommunications engineer, was detained on June 16, 1986. Pattis, 49 years old at the time, had been working for a U.S. company, Cosmos Engineers, at Iran’s primary satellite ground station in Assadabad.

In 1986, Iraqi jets bombed the telecommunications facility, prompting Iranian authorities to investigate and ultimately arrested Pattis for working on behalf of the U.S. government. Pattis appeared on Iranian state television and claimed that he had spied for the CIA, which the State Department denied. The Swiss Embassy in Tehran confirmed his arrest, but Tehran barred anyone from meeting with him. In 1987, Iran sentenced Pattis to 10 years in Evin prison.

His sister and mother visited him in May 1991, fearing for his health and seeking his release. Pattis served half of his sentence before ultimately being freed in 1991. He arrived back in the United States on October 7 of that year.

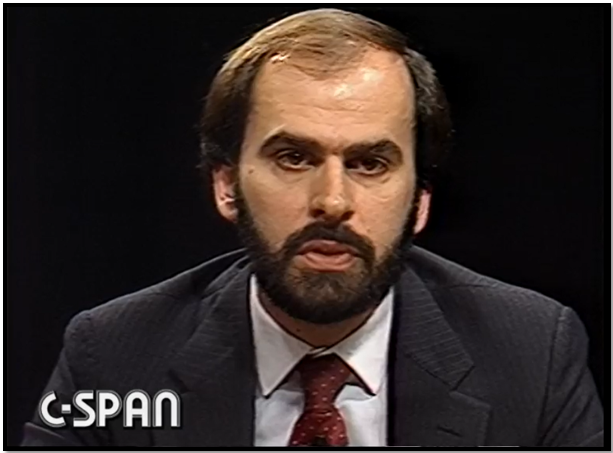

Gerald Seib (January 1987 - February 1987)

Gerald Seib, an American journalist, was detained on Jan. 31, 1987. Seib, 30 years old at the time, was covering the Middle East for The Wall Street Journal. He had been invited to Iran with dozens of other reporters to cover the Iran-Iraq War. Seib was accused of being a spy for Israel and held in Evin prison. He had allegedly asked “sensitive” questions about the war and U.S.-Iran relations. Seib was released days later to Swiss custody and arrived in Switzerland on Feb. 7, 1987. Iran cited misunderstandings for his brief detention at Evin prison. “'I'm still not sure why I was detained, or how I was released,” he said after arriving in Zurich. “Any suggestion that I was involved in any kind of espionage is completely false. I'm a journalist.”

Gerald Seib, an American journalist, was detained on Jan. 31, 1987. Seib, 30 years old at the time, was covering the Middle East for The Wall Street Journal. He had been invited to Iran with dozens of other reporters to cover the Iran-Iraq War. Seib was accused of being a spy for Israel and held in Evin prison. He had allegedly asked “sensitive” questions about the war and U.S.-Iran relations. Seib was released days later to Swiss custody and arrived in Switzerland on Feb. 7, 1987. Iran cited misunderstandings for his brief detention at Evin prison. “'I'm still not sure why I was detained, or how I was released,” he said after arriving in Zurich. “Any suggestion that I was involved in any kind of espionage is completely false. I'm a journalist.”

Daniel Baumann (January - March 1997)

Daniel Baumann, a dual Swiss-U.S. citizen, was detained in January 1997 in Tehran. Baumann, a Christian missionary, had traveled to Iran with Stuart Timm, a South African citizen, to explore opportunities in the country. They attempted to return to Turkmenistan, where they had been working, when border guards seized their passports and ordered them to Tehran to secure new documents. In Tehran, the two were detained and interrogated for four days. They were then transferred to Evin prison, where Baumann’s condition deteriorated. After roughly two months, Baumann was released in mid-March. Timm had been released in February. Iran’s penal code prescribes the death penalty for proselytizing and attempts by non-Muslims to convert Muslims.

Dariush Zahedi (July - November 2003)

Dariush Zahedi, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on unspecified espionage charges in early July 2003. Zahedi, age 37 at the time, was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, specializing in Iran and the Middle East.

Dariush Zahedi, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on unspecified espionage charges in early July 2003. Zahedi, age 37 at the time, was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, specializing in Iran and the Middle East.

Zahedi had visited Iran in June 2003 to see his family. Zahedi was visiting his brother’s office in Tehran when authorities raided the premises and detained him. The Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) placed Zahedi in solitary confinement at Evin prison under suspicions of espionage and that he had allegedly organized protests during the 1999 student demonstrations. After 40 days, Zahedi was transferred to the judiciary-controlled area of Evin prison.

Zahedi’s family visited him twice and chose to not publicize the case due to concerns that Iranian authorities would retaliate. He was freed on bail in November 2003 on unknown terms.

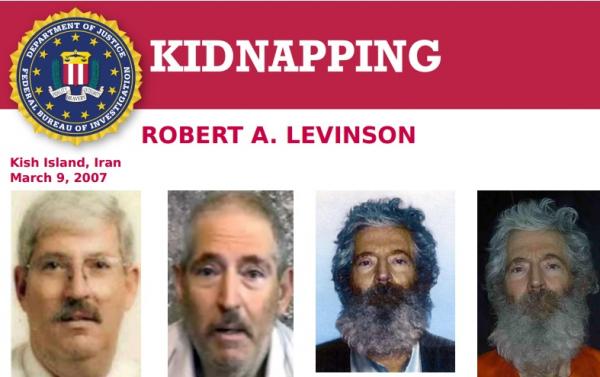

Robert Levinson (March 2007- )

Former FBI agent Robert Levinson went missing on March 9, 2007, during a visit to Kish Island. Initial reports indicated that he was researching a cigarette smuggling case as a private investigator. “He's a private citizen involved in private business in Iran,” the State Department said in 2007. Iran has denied knowing the status or location of Levinson, who was 58 when he disappeared.

Levinson’s family first received evidence that he was alive in November 2010. In a 54-second video, Levinson asked for a U.S. government response to his captors' demands, which have not been publicized. In March 2011, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that new information indicated that Levinson was being held in Southwest Asia, without specifying any particular countries. His unidentified captors sent a set of photographs to his family the following month. Levinson, dressed in an orange prison jumpsuit, held a sign bearing a different message in each photo. “This is the result of 30 years serving for USA,” one read. In December 2011, Levinson’s family released a statement he had taped a year earlier.

Levinson’s family first received evidence that he was alive in November 2010. In a 54-second video, Levinson asked for a U.S. government response to his captors' demands, which have not been publicized. In March 2011, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that new information indicated that Levinson was being held in Southwest Asia, without specifying any particular countries. His unidentified captors sent a set of photographs to his family the following month. Levinson, dressed in an orange prison jumpsuit, held a sign bearing a different message in each photo. “This is the result of 30 years serving for USA,” one read. In December 2011, Levinson’s family released a statement he had taped a year earlier.

In 2013, the Associated Press reported that Levinson had been working on a private contract for U.S. intelligence. In late 2013, the family acknowledged that his visit to Kish Island was partly related to his contract work for the CIA. Levinson served in the FBI and Drug Enforcement Administration for 28 years, where he focused on investigating organized crime in Russia. He retired from the FBI in 1998 and began working as a private investigator.

In January 2016, following a prisoner swap that coincided with implementation of the Iran nuclear deal, Secretary of State John Kerry said that Iran agreed to deepen coordination in finding Levinson. White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest later clarified that the government had reason to believe that Levinson is no longer in Iran, and had thought so for several years.

In March 2017, the White House issued a statement marking the 10-year anniversary of Levinson’s disappearance. “The Trump Administration remains unwavering in our commitment to locate Mr. Levinson and bring him home,” it said. Also in March, Levinson’s family filed a lawsuit against Iran in a federal court.

In October 2019, Iran acknowledged that Levison had an ongoing case at court in Tehran. The United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances said Iran responded to an inquiry by Levinson’s family made in 2016. “According to the statement of Tehran’s Justice Department, Mr. Robert Alan Levinson has an ongoing case in the Public Prosecution and Revolutionary Court of Tehran,” the U.N. body reported. Iran later clarified that an open case on Levinson “was a missing person” matter and not a sign that Levinson was detained and prosecuted by Tehran.

On Nov. 21, 2019, ABC News reported that Levinson’s family had what appeared to be Iranian government documents suggesting that Levinson was arrested by Ministry of Intelligence agents on Kish Island. The two-pages were obtained by the Levinson family in 2010. They revealed Levinson’s arrest was made after a “judicial order” by military prosecutor Hojatol-Islam Bahrami. “He is here using the cover of a tourist while conducting various meetings, taking pictures and gathering information,” an Iranian counterintelligence officer reported in the file.

Another document revealed that a military commander at Kish Air Base, where Levinson was allegedly held, asked for instruction after Levinson’s health deteriorated, and he went into a coma. “A doctor examined him and he was diagnosed to have diabetes and noted that he is not in a good condition and ordered to transfer him to a hospital,” said Colonel Mohammad Reza Jalali. “In regard to the sensitivity and importance of this matter and the accused, please give us the necessary orders that should be taken in this regard.” The documents did not detail any action that followed.

"We have always believed that someone on Kish Island made a horrible mistake in arresting Bob -- which is confirmed by these documents. Now is the time for Iranian authorities to do what they know is right and send this wonderful husband, father and grandfather home to us," said Levinson’s wife, Christine.

On March 9, 2020, a U.S. federal judge held Iran responsible for Levinson’s “hostage taking and torture” and entered a default judgment because Iran did not respond to the lawsuit. The family sought more than $1.5 billion in damages.

On March 25, 2020, the wife and children of Levinson announced “with aching hearts” that U.S. officials informed them that he had died in Iranian custody at some point before the COVID-19 pandemic. Levinson had been on a rogue CIA mission when he disappeared on Kish Island. He was the longest-held hostage in U.S. history.

Haleh Esfandiari (May - August 2007)

Haleh Esfandiari, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on May 9, 2007 by the MOIS. Esfandiari, age 67 at the time, was Director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, a think tank in Washington, D.C. She had written a book (published in 1997) and a Foreign Policy article (published in 2005) on the struggles of Iranian women since the 1979 revolution. On May 21, 2007, the judiciary charged Esfandiari with espionage and endangering national security.

Esfandiari had traveled to Iran in December 2006 to visit her elderly mother. She was robbed at knifepoint on December 30 and lost her U.S. and Iranian passports. She was consequently unable to leave the country. Esfandiari was interrogated by the MOIS when she attempted to replace her passport. The interrogations spanned six weeks and centered on her work at the Wilson Center. On May 7, 2007, Esfandiari was summoned to the MOIS and then taken to Evin prison. On May 30, judiciary Spokesperson Ali Reza Jamshidi announced that Esfandiari was charged with “endangering national security through propaganda against the system and espionage for foreigners.” The State Department and Members of Congress called for Esfandiari’s release.

Former Wilson Center President Lee Hamilton wrote a letter to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on June 29 pleading for Esfandiari’s release and citing her contributions to the general knowledge of Iranian culture. Hamilton received a letter from Iran’s representative to the United Nations, who claimed that “necessary measures [would] be taken as soon as possible.” Esfandiari was ultimately released on a $320,000 bail on Aug. 21, 2007, when Esfandiari’s mother offered her apartment as collateral. She had spent 105 days in solitary confinement.

Ali Shakeri (May - September 2007)

Ali Shakeri, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on May 8, 2007 by the MOIS for endangering national security. Shakeri, age 59 at the time, worked for the Center for Citizen Peacebuilding at the University of California, Irvine. He was also a founding member of the Ettehade Jomhourikhanan-e Iran, a political organization dedicated to democratization for Iran.

Shakeri had returned to Iran in March 2007 to visit his ailing mother, who died while he was there. Authorities detained Shakeri when he was at Tehran’s airport preparing to leave the country. Shakeri was reportedly interrogated almost daily. On June 8, Iran confirmed that he was being held in Evin prison on charges of endangering national security. The State Department condemned the detainment and called the charges “ridiculous.”

Shakeri was ultimately freed on Sept. 25, 2007 when his family posted a bail of approximately $107,000. He arrived back in the United States on October 9 after a judge permitted him to leave Iran.

Kian Tajbakhsh (May - September 2007; July 2009 - January 2016)

Kian Tajbakhsh, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on May 11, 2007, and again on July 9, 2009. Tajbakhsh, age 45 at the time of his first detention, was a professor at the New School in New York City. He had also advised the Open Society Institute and coordinated dialogue between Iranian and Dutch municipalities.

On May 11, 2007, the MOIS detained Tajbakhsh at his home in Tehran. He was charged with spying and was subsequently held in Evin prison for four months. Columbia University President Lee Bollinger and Dean John Coatsworth called for Tajbakhsh’s release. He was freed on September 19 on a bail of approximately $110,000 after Columbia invited President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to speak at the university.

On July 9, 2009, Tajbakhsh was again detained at his home as part of the crackdown on Green Movement protests that followed Ahmadinejad’s disputed reelection. During a mass trial on October 18, Tajbakhsh was convicted of espionage and sentenced to at least 12 years in prison. The White House and State Department as well as politicians, universities, and celebrities issued statements condemning Tehran’s harsh sentence – which included solitary confinement – and called for his release. On November 26, the IRGC levied additional spying charges against Tajbakhsh.

On Feb. 7, 2010, Tajbakhsh successfully appealed his sentence, which was reduced to five years. He spent eight months in Evin prison before being permitted to serve out the rest of his sentence on parole in Tehran. He was finally freed on Jan. 16, 2016, on the same day that the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was implemented.

Nik Moradi (October 2007 - April 2008)

Nik Moradi, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on Oct. 31, 2007. Moradi, age 57 at the time, was a businessman who owned various clothing stores. He was detained on charges of espionage.

Moradi arrived at Tehran’s airport on Oct. 31, 2007. He was approached by authorities and handcuffed, blindfolded, and driven to an unknown location. Moradi was placed in solitary confinement for the next five months and experienced regular interrogations, during which he was accused of espionage. He was allegedly physically and psychologically tortured as well as sexually assaulted. Moradi falsely confessed that he had connections with the FBI, CIA, and other intelligence organizations.

A judge deemed Moradi not guilty and ordered his release on April 15, 2008, in exchange for his family posting a $500,000 bail. Moradi finally left Iran in November 2008.

Reza Taghavi (May 2008 - October 2010)

Reza Taghavi, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained in May 2008 after he gave $200 to an organization called Tondar that sought an end to the Islamic Republic. Taghavi, a businessman from Los Angeles, claimed that he was tricked into giving the money. He was in his late 60s at the time and was held in Evin prison. Taghavi was released in October 2010 and vowed to sue Tondar. “They (judicial authorities) released me to see what I’m going to do against those people that they gave me the money for,” he said in an interview with Reuters. “I am going to file a suit against them.”

Esha Momeni (October 2008 - August 2009)

Esha Momeni, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on Oct. 15, 2008. Momeni, age 29 at the time, was a graduate student of the School of Communications, Media and Arts at California State University, Northridge. Her master’s thesis was focused on the Iranian feminist movement. Momeni was charged with propagandizing against the regime.

Momeni had visited Iran in August 2008 as part of her thesis research to conduct interviews with the One Million Signatures Campaign, an organization seeking to change discriminatory laws against women in Tehran. On October 15, she was pulled over for an alleged traffic violation. Security officials then entered her home and collected research and computer materials related to her project. That same day, Momeni was taken to Evin prison, where she experienced 19 interrogations. On November 4, judiciary Spokesperson Alireza Jamshidi announced that Momeni had been charged with “acting against national security.”

Momeni’s family and friends as well as women activists launched an online petition calling for her release, while professors at California State University held news conferences on her contributions to cultural understanding. On November 10, Momeni was released on bail when her family offered their home as collateral. But authorities placed Momeni under a travel ban and seized her passport. She was finally allowed to leave Iran on Aug. 11, 2009, and returned to Los Angeles.

Roxana Saberi (January - May 2009)

Roxana Saberi, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on Jan. 31, 2009. She was 31 years old when arrested and worked as a freelance news correspondent for NPR, IPS and ABC Radio. Iran had previously revoked Saberi’s two press accreditations for FNS (Feature News Story) and BBC. She was initially detained for purchasing alcohol, which is illegal in Iran. The judiciary confirmed her detention on March 3 but did not clarify the charges. Then President Barack Obama, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and other politicians urged Iran to free Saberi. The presidents and editors of several news organizations including NPR, The Wall Street Journal, and BBC, also signed an open letter calling for her release. On April 8, the judiciary charged Saberi with espionage and sentenced her to eight years in Evin prison.

On April 21, Iranian film director Bahman Ghobadi published an open letter urging Saberi’s freedom. Four days later, BBC reported that Saberi had gone on a hunger strike. An appeals court dismissed the charges against Saberi on May 10, and a day later she was released from prison.

Sarah Shourd (July 2009 - September 2010), Joshua Fattal and Shane Bauer (July 2009 - September 2011)

Three American citizens — Joshua Fattal, Sarah Shourd and Shane Bauer — were detained by Iranian authorities on July 31, 2009. Fattal, then 27 years old, was a graduate of University of California, Berkeley and co-director of an environmental education center in Oregon. Shourd, 31, was an English teacher working in Damascus, Syria. Bauer, 27, was Shourd’s significant other and a freelance photojournalist with proficiency in Arabic. They were charged with espionage.

Fattal, Shourd and Bauer traveled to Iraqi Kurdistan in July 2009 for vacation. On July 31, they hiked to Ahed Awa waterfall, a popular tourist spot, and continued walking until they inadvertently crossed the border into Iran. Iranian authorities detained Fattal, Shourd and Bauer and sent them to Evin prison, where they were initially held in solitary confinement. President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for their release, as did other government officials and celebrities.

Sarah Shourd was released on humanitarian grounds on Sept. 14, 2010 on a $465,000 bail reportedly paid by the Sultan of Oman. Shourd was still a defendant in the case but did not have to return to Iran for trial on behalf of her declining health.

Fattal and Bauer were convicted of espionage and illegal entry on Aug. 20, 2011 and sentenced to eight years in prison. In September, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad told U.S. media that Bauer and Fattal would be freed shortly. On September 21, Bauer and Fattal were finally freed and taken to Oman by a diplomatic convoy. Oman, which had coordinated with U.S. and Swiss diplomats throughout negotiations, had paid the approximately $1 million bail for the two men.

Amir Hekmati (August 2011 - January 2016)

Amir Hekmati was arrested in August 2011 while visiting his grandmother in Iran. Hekmati, age 28 at the time, was charged with espionage, waging war against God, and corruption on earth. In January 2012, he was convicted and sentenced to death. He was the first American to receive the death sentence in Iran since the revolution. But in March 2012, a retrial overturned the espionage conviction and instead charged him with “cooperating with hostile governments.” He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

On Dec. 30, 2015, Tasnim news agency reported that prison officials were considering a conditional release of Hekmati for good conduct. His lawyer, Mahmoud Alizadeh Tabatabaei told the outlet that he was eligible for probation under Iranian law. In January 2016, Hekmati’s family said that he was allowed to receive medical treatment outside of prison. He was escorted from Evin Prison to hospital for medical tests, including a CT scan, due to a lymph node swelling in his face and neck.

Hekmati was a former U.S. Marine and a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen. His parents were born in Iran. Hekmati was born in Flagstaff, Arizona in 1983 and grew up in Nebraska and Michigan. He served in the Marines from 2001 to 2005, including a six-month deployment to Iraq. He later worked as a government contractor doing linguistic and translation work.

In January 2016, Congressman Dan Kildee, whose constituents include the Hekmati family, implored President Obama to mention Amir Hekmati by name during his State of the Union address. Kildee said he would have Sarah Hekmati, Amir’s sister, to be his guest at the address. “Amir Hekmati has been unjustly held in Iran for nearly 1,600 days. It is long past time for Iran to release him so he can be reunited with his family in Michigan,” Congressman Kildee said. “Having Sarah join me at the State of the Union will serve as an important reminder of Amir’s continued imprisonment and the pain their family continues to endure. We continue to press for his release and do everything we can to bring him home.” On Jan. 16, 2016, he was released as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

Afsaneh Azadeh (May 2012 - May 2013)

Afsaneh Azadeh, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen, was detained on May 13, 2012. Azadeh, age 43 at the time, was general manager of HeavyLift International, a United Arab Emirates-based aviation cargo company. She was charged with endangering national security.

Azadeh arrived at Tehran’s airport on May 13, 2012 to visit her mother. The IRGC detained Azadeh as she was leaving the airport and drove her to Evin prison. The judiciary accused her of collaborating with the CIA and aiding the pro-democracy Green Movement. Over the next four months, Azadeh was held in solitary confinement while undergoing interrogations. She was also poisoned by guards and subjected to two mock executions.

Azadeh was freed from jail in September after signing over the deed to her mother’s house and falsely confessing to being a CIA agent. She remained under house arrest. Azadeh was released from house arrest in November 2012 and finally left the country in May 2013.

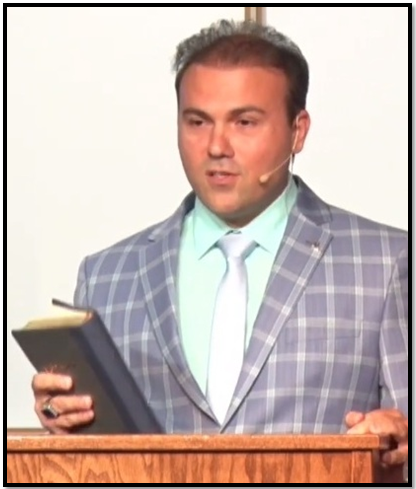

Saeed Abedini (July 2012 - January 2016)

Rev. Saeed Abedini was detained on July 28, 2012, and initially imprisoned in September 2012. Abedini was 32 at the time and had been in Iran to visit family and construct orphanages in partnership with Iranian Christians. His closed trial was held on Jan. 22, 2013. He was convicted and sentenced to eight years in prison, reportedly for “undermining national security.”

Rev. Saeed Abedini was detained on July 28, 2012, and initially imprisoned in September 2012. Abedini was 32 at the time and had been in Iran to visit family and construct orphanages in partnership with Iranian Christians. His closed trial was held on Jan. 22, 2013. He was convicted and sentenced to eight years in prison, reportedly for “undermining national security.”

Abedini was born in Iran in 1980 and later converted to Christianity. In 2002, he met his future wife Naghmeh, a U.S. citizen of Iranian descent who was visiting Iran. The couple played a prominent role in establishing 100 underground churches in Iran for 2,000 Christian converts. Iranian Muslims who convert to Christianity are not allowed to worship in established churches, although Christianity is legal in Iran, and the constitution stipulates proportionate representation in parliament for various Christian minorities. Under pressure from the regime, the couple moved to the United States in 2005.

Abedini was ordained as a minister in 2008. During a trip to Iran in 2009, authorities reportedly threatened him with death for his conversion to Christianity and told him he could only return to Iran if he ceased his underground church activities. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen through marriage in 2010. Between 2009 and 2012, he traveled to and from Iran eight times before his detention in 2012 on his ninth trip. His family in Tehran was periodically allowed to visit him in prison, but he was not permitted to contact his wife and two children in the United States. On Jan. 16, 2016, Abedini was released as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

Jason Rezaian (July 2014 - January 2016)

Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian was detained on July 22, 2014. He was 38 at the time. Charges against him included espionage, “collaborating with hostile governments,” and “propaganda against the establishment.” The indictment specifically cited correspondence with President Obama. According to Iranian press reports, Rezaian allegedly applied for a job with the administration. He reportedly wrote to Obama, “In Iran, I’m in contact with simple laborers to influential mullahs.”

On May 26, 2014, Rezaian went on trial in Tehran’s Revolutionary Court, which handles national security cases. He denied the charges against him “I carried out all my activities legally and as a journalist,” he said. In a press conference on Oct. 11, 2015, Judiciary spokesman Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei confirmed that Rezaian had been found guilty but did not provide details on his sentence or the specific charges on which he was convicted. Rezaian’s family and colleagues strongly condemned the conviction. The Post's Executive Editor Martin Baron said that “Any fair and just review would quickly overturn this unfounded verdict.” On Nov. 22, 2015, Iran's state news agency announced that Rezaian had been sentenced. But the Mohseni-Ejei said that he could not reveal further details.

On Christmas Day 2015, Rezaian’s wife and mother were allowed to visit. “This is the first time in the year that I have been visiting him in Evin Prison that I could spend an extended time there and bring him his first home-cooked meal in months,” his mother, Mary Rezaian, said in an email to The Washington Post.

Rezaian was a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen. His father moved to the United States from Iran in 1959, and his mother was from Chicago. Jason was born in California in 1976. He moved to Iran to work as a journalist in 2008, and became The Post’s Tehran correspondent in 2012. Rezaian’s Iranian wife, Yaganeh Salehi, a correspondent for the Emirates-based paper The National, was also detained in 2014. She was released 10 weeks later. On Jan. 16, 2016, Rezaian was released as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari (May 2015 - January 2016)

Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari, a former California-based carpet seller and F.B.I. consultant, was arrested in May 2015 by Iranian intelligence agents when he tried to leave the country. His lawyer said his arrest had been “the result of a misunderstanding.” He reportedly opted to stay in Iran immediately following his release in January 2016 as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

Siamak Namazi (October 2015 - September 2023)

Dubai-based businessman Siamak Namazi was arrested in mid-October 2015. On July 11, 2016, Tehran’s prosecutor announced that Namazi had been indicted but did not specify the charges. On October 18, 2016, after being tried without access to a lawyer, Namazi was sentenced to 10 years in prison for collaborating with a foreign government.

Namazi is the son of a former governor of the oil-rich province of Khuzestan in western Iran, according to The Washington Post. His family came to the United States in 1983 when he was a boy. He became a U.S. citizen in 1993. After graduating from college, Namazi returned to Iran for military service, which is compulsory there. From 1994 to 1996, he worked as a duty officer with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning in Tehran.

In 1998, Namazi founded Future Alliance International, a Washington D.C.-based consulting company focused on the risk of doing business in Iran. He came to see Iranian-Americans as a potential asset to his home country. “The new generation must be made to feel that no matter how much time elapses they will be welcomed and treated with respect in the land of their parents,” he wrote in 1998 for The Iranian. He suggested that Iran’s recognition of dual citizenship would be a good first step. “Iranian-Americans are a formidable force in helping mend the bridge between Iran and the United States,” he stated in a 1999 co-authored paper.

Namazi later worked as Managing Director at a family consulting firm founded in Tehran that later moved to Dubai, the Atieh Group. In 2005, he was a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He also did a stint at the National Endowment for Democracy in 2006. He then worked for a few different energy consulting groups in Dubai. In 2013, Namazi warned that sanctions unintentionally created shortages of life-saving medical supplies and drugs in Iran. He was General Manager of Access Consulting Group, a Dubai-based consultancy focused on energy, before moving on to his most recent position at Crescent Petroleum. Namazi holds degrees from the London Business School and from Rutgers and Tufts Universities.

On July 11, 2016, Tehran’s prosecutor announced that Namazi had been indicted but did not specify the charges. On October 17, the Mizan news agency, the judiciary news service, posted a video that appeared to show Namazi in the hours immediately following his arrest. The short clip was an anti-American montage that showed images of a captured American surveillance drone, Jason Rezaian (a dual-national journalist who was accused of spying for the United States), U.S. sailors kneeling before being detained by Iranian forces and more.

On October 18, 2016, after being tried without access to a lawyer, Namazi was sentenced to 10 years in prison for collaborating with a foreign government. Five other defendants were also convicted and given similar sentences, including Siamak Namazi’s father Baquer. Namazi and his father were being held in Evin Prison by the IRGC.

Siamak Namazi’s brother Babak spoke out against the sentences, calling them unjust. “My father has been handed practically a death sentence,” Babak wrote. “Siamak’s only crime has been to speak out against the negative effects of sanctions.” Babak was referring to an Op-Ed essay Namazi wrote for The New York Times in 2013.

In April 2017, Namazi’s lawyer, Jared Genser, called on President Trump to secure the release of Namazi and his father. “If not resolved quickly, the Namazi cases could have an outsized impact on the trajectory of Iran-US relations because both men are in rapidly declining health,” Genser stated. “In our view, something happening to the Namazis would be devastating not just to one side, but to both sides.” “For either or both of the Namazi to die on President Trump’s watch would be a public and catastrophic failure of his negotiating skills.”

Siamak Namazi’s health has declined since his arrest following prolonged periods of interrogation and a hunger strike in 2016. In August 2017, a Tehran appeals court upheld the convictions of both Siamak and his father, Baquer. “The Namazis are innocent of the charges on which they were convicted and they are prisoners of conscience, detained in Iran because they are American citizens,” international counsel to the family, Jared Genser, said in a statement.

In September 2017, a U.N. panel of international legal experts reportedly concluded that the imprisonment of the Namazis was illegal and that they should be freed.

On Aug. 26, 2018, the Tehran Appeals Court denied the appeals of Siamak and Baquer Namazi, upholding their convictions of collaborating with the U.S. government. The Namazis U.S.-based lawyer Jared Genser condemned the move as a “cruel and unjust decision” of the court.

On Feb. 7, 2020, the Ghanoon Telegram messaging app channel published a letter that Namazi had written from Evin Prison. In the letter, Namazi asked Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi why he had not been granted furlough while other prisoners were allowed to go on temporary leave. “For the past four years, while enduring punishment for a crime I did not commit, I have been trying to restore my rights with the help of almighty God within the laws of our beloved country,” Namazi wrote. “Four years and four months have passed without a break… Meanwhile I have witnessed the brother of a senior state official being given furlough just hours after being put into prison.”

On March 2, 2020, the Namazi family’s lawyer, Jared Gensler, reported that his client was at “serious risk” of contracting the virus. “To keep Siamak at Evin prison in the midst of a coronavirus outbreak and without access to testing or even basic medicines constitutes cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in violation of Iran’s obligations under the Convention Against Torture,” said Genser. On March 3, Iran’s judiciary announced that it would grant furloughs to 54,000 healthy prisoners to help stem the spread of the virus. It was unclear whether Namazi would also be granted furlough.

On Oct. 1, 2022, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres announced that Namazi had been “released from detention.” His lawyer clarified that he had been released on a one-week furlough. The United States welcomed the move and thanked Guterres, Switzerland, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and the Britain for working to help the Namazi family. “Our efforts are far from over,” State Department Spokesperson Ned Price said. “We remain committed and determined to securing the freedom of all Americans unjustly detained in Iran and elsewhere.” Namazi's furlough was extended on October 8, but he was forced to return to prison four days later.

On January 16, 2023, Namazi went on a hunger strike. In an open letter, he urged President Biden to do more to free him and the other Americans held in Iran. “In the past I implored you to reach for your moral compass and find the resolve to bring the US hostages in Iran home. To no avail,” he wrote. “Not only do we remain Iran’s prisoners, but you have not so much as granted our families a meeting.”

On August 10, 2023, Namazi was released from Evin Prison into house arrest at a hotel in Tehran as part of a deal between the United States and Iran. On Sept. 18, 2023, Iran released him and four other Americans.

Matthew Trevithick (December 2015 - January 2016)

On December 7, 2015, Matthew Trevithick, an American student studying Farsi at Tehran University, was arrested and accused of trying to overthrow the Iranian government. He denied the charges and was placed in solitary confinement for 29 days. He was finally released on January 16, 2016, after 40 days in Evin Prison.

Baquer Namazi (February 2016 - October 2022)

Baquer Namazi, a dual American-Iranian citizen, was reportedly arrested on Feb. 22, 2016, four months after his son Siamak was detained. The elder Namazi, age 80 at the time of his arrest, was a former provincial governor and UNICEF representative who worked in several countries, including Kenya, Somalia and Egypt. His work largely focused on aid for women and children affected by war. Baquer Namazi had most recently ran Hamyaran, an umbrella organization of a number of different Iranian NGOs. On Oct. 18, 2016, he was sentenced to 10 years for allegedly cooperating with U.S. intelligence agencies to spy on Iran.

Namazi’s arrest occurred soon after a prisoner swap between the United States and Iran that coincided with the implementation of the nuclear deal. He and his son were denied access to their family’s lawyer. The elder Namazi had a serious heart condition, as well as a host of other medical conditions that required medical attention, according to his wife.

In February 2016, Secretary of State John Kerry told a Senate panel hearing that he was engaged on the issue of Namazi’s detention but could not comment due to privacy considerations.

In April 2016, judiciary spokesman Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejehi suggested both Namazis could be swapped for Ahmad Sheikhzadeh— an Iranian consultant to the United Nations held in the United States on suspicion of tax and money laundering charges for helping violate sanctions. Ejehi, however, emphasized that he had just “heard words from here and there though nothing has been officially conveyed to the judiciary.”

Namazi’s other son, Babak spoke frequently about his father and brother’s imprisonment. In November 2016, in an interview with Steven Inskeep, host of NPR’s Morning Edition, Babak discussed the impact of the ordeal on him and his family.

“As a family, we're devastated. It's just being bombarded for the past year with one horrible event after another. I have half my family ripped away from me. I'm wondering if I will see my father again. It's very horrible to say this, but he has been in essence handed a life sentence. A 10-year sentence for an 80-year-old man is a life sentence. But I have to do all I can to save my father's life and my brother's.”

Babak urged President Trump to take “personal responsibility” for negotiating his father and brother’s release. Baquer Namazi and his son Samiak currently remain jailed in Evin Prison.

In June 2017, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres appealed to President Rouhani in a private letter to release Baquer on humanitarian grounds.

In August 2017, a Tehran appeals court upheld the convictions of both Namazis. Baquer’s health has deteriorated rapidly. “He is 81-years-old, previously had a triple bypass surgery, has lost 30 pounds in prison and suffers from shortness of breath, dizziness, bouts of confusion, and recently lost his hearing in one ear,” international counsel to the family, Jared Genser, said in a statement.

On Sept. 5, 2017, the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention ruled that Siamak and Baquer Namazi were not granted a fair trial under internationally recognized law and called for their immediate release.

On Sept. 19, 2017, Baquer underwent surgery to receive a pacemaker. One week prior, IRGC guards had refused to take him to the hospital despite being advised by cardiologists, prompting pleas from his family. Three days later, U.N. Secretary General Guterres urged President Rouhani to release Namazi on humanitarian grounds during a meeting in New York.

On Jan. 15, 2018, Baquer was rushed to the hospital after a severe drop in blood pressure and irregular heartbeat. He was granted a four-day medical leave beginning on January 28. He was told to report to the government’s medical examiner on February 4, and that his leave would be extended until then. The examiner recommended a three-month leave on medical grounds. But on Feb. 6, 2018, Namazi received a call ordering him to return to Evin prison.

On Feb. 7, 2018, the White House issued a statement calling for the immediate release of Namazi and all other U.S. citizens detained in Iran.

On Aug. 26, 2018 the Tehran Appeals Court denied the appeals of Siamak and Baquer Namazi, upholding their convictions of collaborating with the U.S. government. The Namazis’ U.S.-based lawyer Jared Genser condemned the move as a “cruel and unjust decision” of the court.

On Aug. 28, 2018, the Center for Human Rights in Iran reported that Namazi had been released on medical furlough “for a considerable length of time” due to complications from his heart condition. He had to report back to Evin Prison weekly and is unable to leave the country to undergo heart surgery, according to his family.

On Oct. 4, 2021, Namazi’s family said that he required urgent surgery to remove a 95 percent to 97 percent blockage in his right internal carotid artery, which supplies blood to the brain. Neurologists in Iran and the United States warned that his risk of death, stroke or heart attack could be 10 percent to 15 percent higher if is forced to undergo surgery in Iran. Namazi would risk contracting COVID-19 in an Iranian hospital. “I am begging for Iran to show mercy and for the international community, President Joe Biden, and U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres to do everything that they can to pressure Iran to lift the travel ban.,” said son Babak Namazi. “My dad deserves to spend whatever little time he has left with his children and grandchildren.”

On Oct. 1, 2022, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres announced that Namazi’s travel ban had been lifted so that he could seek medical treatment abroad. The United States welcomed the move and thanked Guterres, Switzerland, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Britain for working to help the Namazi family. “Our efforts are far from over,” State Department Spokesperson Ned Price said. “We remain committed and determined to securing the freedom of all Americans unjustly detained in Iran and elsewhere.” On October 5, Namazi flew to Oman and then to the United Arab Emirates for treatment.

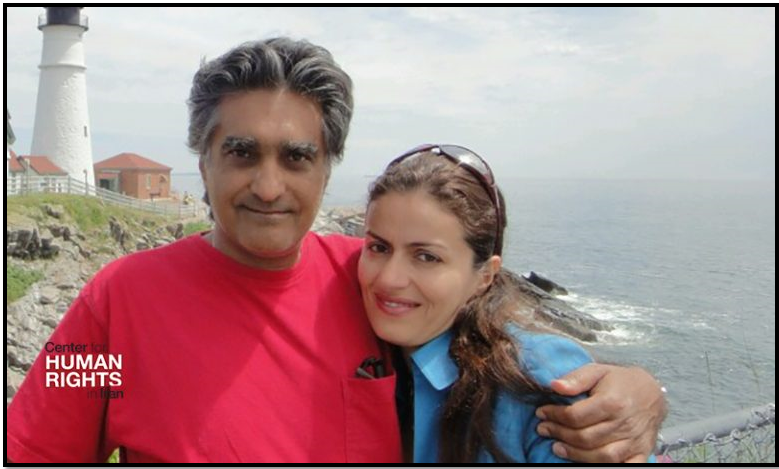

Karan Vafadari (July 2016- July 2018)

Karan Vafadari, a dual American-Iranian citizen, and Afarin Niasari were arrested by the IRGC intelligence organization in July 2016 and then held at Evin Prison. Details about their case were only published in December 2016. The husband and wife reportedly managed an art gallery in Tehran. Niasari, a permanent U.S. resident, was apprehended by IRGC agents at Imam Khomeini airport when she attempted to visit family abroad, according to Vafadari’s sister. Soon after, Niasari was forced to call her husband and ask him to come to the airport, where he too was apprehended. The next day, they were brought back to their home handcuffed, while IRGC agents destroyed works of art hanging on their walls.

No formal charges were immediately brought against Vafadari and Niasari, however, prosecutors alluded to the pair hosting mixed-gender parties for foreign diplomats and Iranians where alcohol was consumed. Vafadari, a Zoroastrian, was not subject himself to the ban on Muslim consumption of alcohol. Iran permits recognized minorities ― Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians ― to drink alcohol in the privacy of their homes.

Vafadari and Niasari ran an art gallery in Tehran, and Niasari also worked as an architect. Vafadari, a dual national, was educated in the United States and had three children who were living in New York City. Vafadari was able to contact family members who visited him a number of times while he was detained.

Vafadari and Niasari ran an art gallery in Tehran, and Niasari also worked as an architect. Vafadari, a dual national, was educated in the United States and had three children who were living in New York City. Vafadari was able to contact family members who visited him a number of times while he was detained.

In August 2016, Jafari Dowlat-Abadi, Tehran’s Prosecutor General described the Vafadari and Niasari home as “a center of immorality and prostitution.” The original charges were initially dropped due to lack of evidence, but reinstated at a hearing in March 2017, during which the pair was denied legal counsel.

New charges were brought against Vafadari and Niasari in a pre-trial hearing on March 8, 2017. The new charges included attempting to overthrow the Islamic Republic and recruiting spies through foreign embassies.

In a letter to the judge dated July 24, 2017, Vafadari said that the charges against him and his wife were completely false. “It is my belief that judiciary officials arrested us for political and financial reasons, without sufficient investigation or evidence,” he wrote.

In a Jan. 21, 2018 letter, Vafadari stated that he had been issued a 27-year prison sentence while his wife Niasari had received 16 years. Vafadari’s sentence included 124 lashes, confiscation of all assets, and a fine, he wrote. He cited charges related to espionage, alcohol consumption, receiving gifts of alcohol, and hosting parties. Vafadari attributed his treatment and sentence to being Zoroastrian and a dual national, with the asset seizure being justified by the court under an unprecedented use of 1928 Civil Code Article 989.

On July 21, 2018, Vafadari and Niasari were released from prison on bail after having their initial sentences reduced earlier in 2018. They were awaiting a final verdict on their appeal request as of late July. Vafadari was still in Iran as of June 2019.

Xiyue Wang (August 2016 - December 2019)

Princeton University graduate student Xiyue Wang was arrested on Aug. 8, 2016 while conducting research in Iran on the administrative and cultural history of the late Qajar dynasty for his doctoral dissertation. He was 35 at the time. On July 17, 2017, Wang was sentenced to 10 years in prison after being convicted of spying, according to Iran’s judiciary spokesman, Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejehi, and Iranian media.

Wang was born in China and was a naturalized American citizen. He studied in China as a child and for his first year of college. He dropped out after securing a chance to study India before heading to the University of Washington in 2003, according to The Washington Post. He studied Russian and Eurasia studies at Harvard University before working as a Princeton in Asia fellow at the law firm Orrick in Hong Kong in 2008. Wang also worked as a translator for the International Committee of Red Cross in Afghanistan. In 2013, he began his doctoral work at Princeton University.

On July 17, 2017, Wang was sentenced to 10 years in prison after being convicted of spying, according to Iran’s judiciary spokesman, Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejehi, and Iranian media. A U.S. citizen “was gathering intelligence and was directly guided by the U.S.,” Ejehi announced at a weekly press briefing on July 16. He noted the sentence could be appealed but did not elaborate or reveal the individual’s name.

Mizan Online News Agency, however, identified Wang. In a report citing an anonymous source, Mizan alleged that Wang had been using his academic research as a cover and was working on a 4,500-page digital archive for “the world’s biggest anti-Iran spying organization.” The article said he infiltrated Iran’s national archive and gathered secret and top-secret intelligence for the U.S. State Department, the Harvard Kennedy School and the British Institute of Persian Studies.

State Department officials told journalists that they were aware of the reports about the dual national but that they would not detail efforts on this case or others for privacy reasons. “The Iranian regime continues to detain U.S. citizens and other foreigners on fabricated national-security-related changes," an official said.

Princeton University also issued a statement saying they were “very distressed by the charges brought against him in connection with his scholarly activities, and by his subsequent conviction and sentence.” Princeton has reportedly been working with Wang’s family, the U.S. government and lawyers to help secure his release.

In August 2017, Iranian authorities denied Wang’s appeal. “I am devastated that my husband’s appeal has been denied, and that he continues to be unjustly imprisoned in Iran on groundless accusations of espionage and collaboration with a hostile government against the Iranian state,” his wife, Hua Qu, said in a statement.

In a November 2017 interview with NBC, Qu stated her husband had attempted suicide and that his condition was “very desperate.” She also called on the Trump administration to work with the Iranian government to bring about his release.

On Aug. 23, 2018, the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention issued a statement calling on Iran to immediately release Wang. It said that Iran had “no legal basis for the arrest and detention” of Wang and that he had been wrongly accused of espionage. The Working Group obtained a response to the petition from the government of Iran. The Iranian response, however, failed to explain how Wang had cooperated with a foreign state against Iran’s government or “how Mr. Wang’s trial on espionage charges posed a national security threat so serious that it warranted a closed hearing.”

On Dec. 7, 2019, Wang was released in Switzerland in exchange for Massoud Soleimani, an Iranian national held in an Atlanta prison for allegedly violating U.S. sanctions. President Donald Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif thanked the Swiss for their help in arranging the trade.

Morad Tahbaz (January 2018 - September 2023)

On Jan. 24, 2018, the IRGC Intelligence Organization detained Morad Tahbaz, a dual American-Iranian citizen, and eight other environmental activists accused of espionage. Their trial began in January 2019 but was delayed until the beginning of August. On November 20, 2019, an Iranian court sentenced Tahbaz to 10 years in prison.

The activists were members of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation conducting research on Iran’s endangered cheetah population. On Oct. 24, 2018, the judiciary charged Tahbaz with “seeking proximity to military sites with the cover of environmental projects and obtaining military information from them.” One of the four charges against him included “sowing corruption on earth,” which typically carries the death penalty. But on Oct. 14, 2019, the judiciary spokesman said that the capital charge had been dropped. The activists still faced charges of “assembly and collusion against national security” and “contacts with U.S. enemy government … for the purpose of spying,” according to the judiciary.

Tahbaz reportedly had cancer and his health continued to deteriorate because he did not receive medication and treatment for more than a year.

In March 2022, Tahbaz was released on furlough when two other British-Iranians, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Anoosheh Ashoori, were released and allowed to leave Iran. Tahbaz, however, was returned to prison later in the month. On July 26, 2022, Iran released Tahbaz on bail with an electronic bracelet, according to his lawyer. Tahbaz was allowed to stay in Tehran with his in-laws and wife, Vida Tahbaz. Vida was barred from leaving Iran. “It's amazing news, but they're still not home,” their daughter Tara told Al-Monitor. “There's still a long way to go to get to that happy ending." In a tweet, the U.S. special envoy for Iran, Robert Malley, thanked Oman for “its help in achieving the furlough” of Tahbaz. “It is high time that he and the three other unjustly detained US citizens return home,” he added.

On Aug. 10, 2023, Tahbaz was released from Evin Prison into house arrest at a hotel in Tehran as part of a deal between the United States and Iran. On Sept. 18, 2023, Iran released him and four other Americans.

Emad Shargi (2018 - 2019; 2020 - 2023)

Emad Shargi, a dual American-Iranian citizen in his early 50s, was first arrested in April 2018 and held in section 2A of Evin prison for eight months. For his first 44 days in prison, he was held incommunicado, with no contact or access to the outside world, including family and legal counsel. While detained, he was repeatedly interrogated and also held in solitary confinement, according to Shargi’s family. He was questioned about his business dealings and travels.

Shargi was released on bail in December 2018. Approximately one year later, in December 2019, he was issued an official document from the Revolutionary Court declaring his innocence and clearing him of all spying and national security charges. But his passport was withheld, and he was not permitted to leave Iran.

On Nov. 30, 2020, Shargi was summoned to court and convicted of espionage without a trial. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison, a family friend told NBC News. His lawyer filed an appeal. On Jan. 14, 2021, the Young Journalists Club, a news agency affiliated with the IRGC, reported that Shargi had been arrested near the western border. From April 2021, he was held in section 2A of Evin prison and was not allowed visitors or access to legal counsel since his arrest, according to his family.

“Nobody has been able to see him in nearly five months,” Shargi’s two daughters, Ariana and Hannah, wrote in The Washington Post in April 2021. “He is trapped in terrible conditions during a deadly pandemic and is being refused a vaccine. We have no way of knowing how he is, except for a couple of short, monitored phone calls.”

Shargi and his wife, Amidi Shargi, were born in Iran but left as children. Emad Shargi completed his higher education in the United States. He received an undergraduate degree from the University of Maryland and a master’s degree from George Washington University. He previously worked in the plastics industry supplying plastics for water bottles and later at a company in Abu Dhabi leasing and selling private airplanes. He and his wife went to Iran in 2017, after their youngest child left home for college. At the time of his arrest in April 2018, he had just started working for the Dutch division of Sarava Holding, a tech investment company.

On Aug. 10, 2023, Shargi was released from Evin Prison into house arrest at a hotel in Tehran as part of a deal between the United States and Iran. On Sept. 18, 2023, Iran released him and four other Americans.

Michael White (July 2018 - June 2020)

U.S. Navy veteran Michael White, 46, from Imperial Beach, California, was arrested on unspecified charges in late July 2018 while visiting his girlfriend in Iran. In March 2019, White was sentenced to two years in prison for insulting the supreme leader and 10 years posting a private photograph publicly.

White arrived in Iran on July 9, 2018 and never made it onto his return flight on July 27, 2018, according to his mother, Joanne White. She last spoke with him on July 13, 2018; she filed a missing-person report when Michael did not return on his scheduled flight. In December 2018, the State Department informed her that White was being held in an Iranian prison and that U.S. officials were seeking access to him through the Swiss embassy in Tehran, which has provided consular services for Americans since 1980.

On March 11, 2019, an Iranian prosecutor said White had been sentenced, but he did not elaborate on the charges. An attorney for the family, Mark Zaid, later said that he was sentenced to two years in prison for allegedly insulting the supreme leader and 10 years for posting a private photograph on social media. Zaid said that he believed the sentences would run concurrently.

In August 2019, Swiss diplomats were granted permission to visit White in prison. The Swiss were told that prison doctors removed melanoma from his back earlier that month. White "continues to have medical issues” related to his cancer and previous chemotherapy treatments, according to a report from the Swiss embassy. He is currently awaiting a ruling on his appeal.

In January 2020, White's mother released audio from a phone conversation she had with him in prison. He alleged that he had been subject to torture and inhuman conditions. "They've done everything to press me," White said. "They put me in isolation. They subjected me to torture conditions—deprivation of food and water numerous times."

On March 19, the State Department announced that White was temporarily released from prison on a medical furlough. He was transferred to a hotel but remained in Iranian custody. His release was facilitated by the Swiss, who represent U.S. interests in Iran. White was required to remain in Iran throughout his furlough. “He’s in very good spirits. But he has some preexisting health conditions that are going to require some attention,” said U.S. Special Representative for Iran Brian Hook.

On March 25, White was admitted to a hospital ward for coronavirus patients after experiencing fever, fatigue, a cough and shortness of breath. White’s family said that he "is an immunocompromised cancer patient and his situation is urgent." They called for an immediate humanitarian medical evacuation to the United States to receive medical treatment. In early May, Switzerland asked Iran to extend White’s medical furlough. White was eventually transferred back to the hotel after his condition improved.

On May 6, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo thanked Switzerland for its efforts. “Our gratitude also goes out to Switzerland, the United States protecting power in Iran for now four decades, for its efforts to extend Michael White’s medical furlough and seeking humanitarian furloughs for Siamak Namazi and Morad Tahbaz and bringing home all U.S. citizens wrongfully detained,” Pompeo told reporters at a news conference.

On June 4, 2020, Joanne White announced that her son had been released. “For the past 683 days my son, Michael, has been held hostage in Iran by the IRGC and I have been living a nightmare. I am blessed to announce that the nightmare is over, and my son is safely on his way home,” she said. Iran exchanged White for an American-Iranian physician imprisoned in the United States for sanctions violations.

Unnamed businessman (2022-2023)

In late 2022, a male U.S.-Iranian citizen was reportedly detained in Iran. He was released on Sept. 18, 2023 as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

Unnamed female former U.N. worker ( - 2023)

On Sept. 18, 2023, Iran released an unnamed woman, a former U.N. worker, as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

Related Material:

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: Fact Sheet on Details

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: US Statements

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: Iran Statements

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: Congressional Reaction

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: New Sanctions

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: Profiles

Iran-US Prisoner Swap: World Reaction

Photo Credits: Seib via C-SPAN; Zahedi via Freedom For Zahedi; Abedini via Keshsih Rasoul - کشیش رسول, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons;