As of April 2022, food prices in Iran were up 43 percent over the previous year largely due to a severe drought, sanctions, inflation, corruption, and government mismanagement. In early May, the government implemented economic reforms intended to help consumers, but prices of bread and other staples spiked. Cooking essentials, such as oil and sugar, were increasingly scarce.

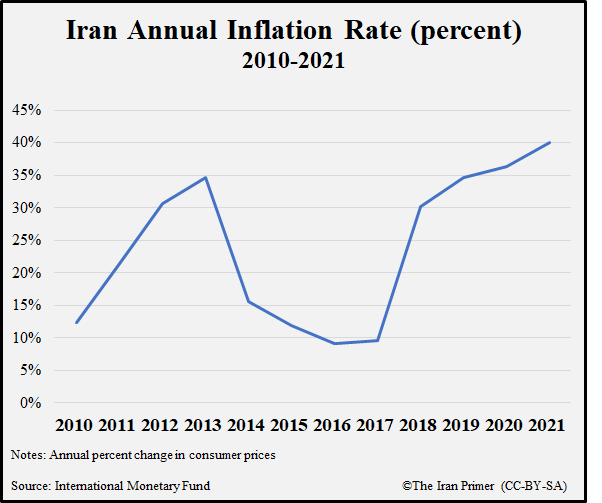

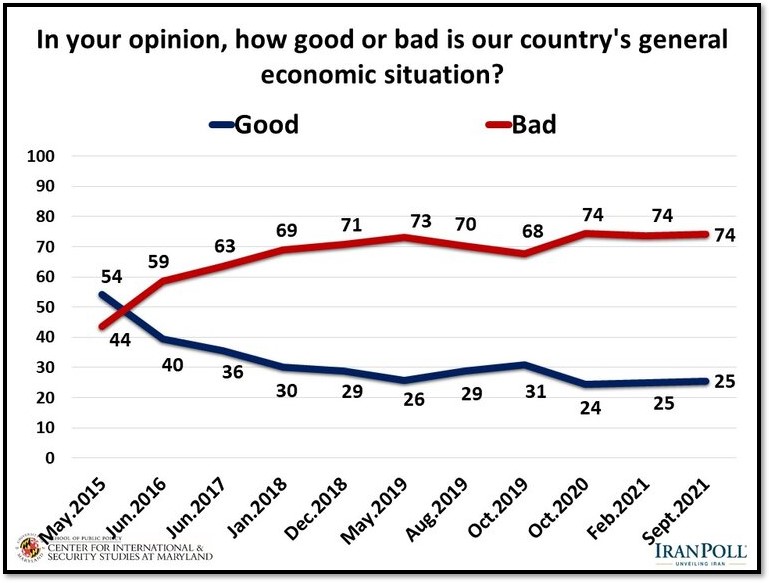

Iranians had already struggled to make ends meet during the three previous years of economic contraction between 2018 and 2021. By early 2022, some 30 percent of households were living below the poverty line, according to government figures. Some experts estimated that at least half of Iran’s 85 million people were living under the poverty line. And inflation for all goods hit 40 percent, the highest since 1994.

The challenges were exacerbated by:

The challenges were exacerbated by:

- The worst drought in a half century, which dragged on for nine months from October 2020 to June 2021, and hurt crop production

- Sanctions, which increased the cost of imported food as well imported parts and machinery for food processing facilities

- The devaluation of Iran’s currency, which increased the cost of imported goods

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a major grain producer, which caused the global price of wheat to rise nearly 20 percent in March 2022

Protests Erupt Over Bread Prices

On May 1, the government announced that it would eliminate an exchange rate subsidy available for the import of wheat, other basic foodstuffs, and some medicines. Many retailers responded by tripling the price of flour-based staples, including bread and pasta. On May 6, protests began in Khuzestan province over bread prices. In the following days, prices for chicken, cooking oil, eggs, milk, and other basics also rose.

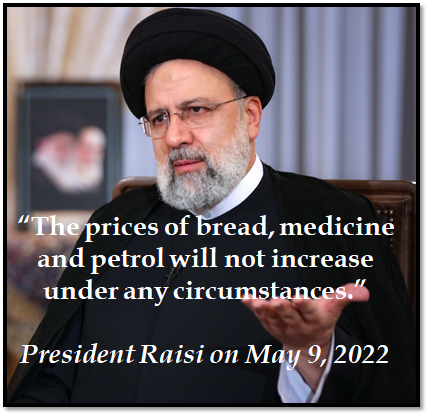

President Ebrahim Raisi called on the public to “not panic” about prices during a televised interview on May 9. He promised to issue electronic coupons in the coming months to allow people to buy a limited amount of bread at subsidized prices. In the meantime, Raisi said that individuals would receive monthly cash transfers of $10 to $13 to help deal with price hikes, but the protests intensified. Major General Hossein Salami, the commander of the Revolutionary Guards, acknowledged the economic “difficulties” and called on the Basij paramilitary to help the people.

The recent protests are not the first time that economic reforms triggered national unrest. Similar protests erupted after the government cut fuel subsidies in November 2019, in turn increasing the consumer price of gasoline. Subsidy reforms are often a political lightning rod because of high inflation and low public trust in government. Since the 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic vowed to help “the oppressed” and improve the material welfare of ordinary people.

The recent protests are not the first time that economic reforms triggered national unrest. Similar protests erupted after the government cut fuel subsidies in November 2019, in turn increasing the consumer price of gasoline. Subsidy reforms are often a political lightning rod because of high inflation and low public trust in government. Since the 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic vowed to help “the oppressed” and improve the material welfare of ordinary people.

But Iran has experienced economic stagnation since sanctions were imposed by the United States, European Union, and United Nations in 2012 during a diplomatic deadlock over Tehran’s controversial nuclear program. The standard of living has not significantly improved in a decade.

Many Iranian economists believe that fuel subsidy reforms or the elimination of the subsidized exchange rate will reduce wastage and corruption—and in turn help the government slow inflation. But successive Iranian governments have failed to communicate the purpose of so-called “economic surgery” or the long-term gains of subsidy reforms, in turn fueling popular resentment.

Government Efforts to Aid the Poor

Economists have long argued that a government-subsidized exchange rate was highly inefficient and did little to help vulnerable households. Since 2016 the government has enabled companies to purchase foreign currency at exchange rates below market prices, effectively providing Iranian importers with billions of dollars in subsidies who did not pass along the subsidized price benefits to food processors, producers or farms.

Economists have long argued that a government-subsidized exchange rate was highly inefficient and did little to help vulnerable households. Since 2016 the government has enabled companies to purchase foreign currency at exchange rates below market prices, effectively providing Iranian importers with billions of dollars in subsidies who did not pass along the subsidized price benefits to food processors, producers or farms.

Proponents of subsidy reform argue that the government could better shield the poor from high prices by giving them cash subsidies. In May 2022, the Raisi government promised to implement new cash transfers to counter price increases as the subsidized exchange rate was eliminated.

The new transfer was originally intended to target only the poorest households. But the initial tranche instead covered the vast majority of the population to avoid backlash. Iran has a long history of using cash transfers to preserve the purchasing power of households. Economists claim that transfers can be efficient.

Public Reaction to Reforms

The reforms implemented by the Raisi administration were originally proposed by the previous government under President Hassan Rouhani, which reflects the consensus among economic policymakers across the political spectrum. “Up to 70 percent of the subsidy funds from the former policy would get lost on their way of reaching the people,” economist Saeed Leylaz, a reformist, told Al Jazeera.

Critics of the reforms have focused mostly on timing and the political consequences, given opposition among politicians with a more populist outlook. Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf – a conservative and the speaker of Parliament – blamed the government for causing “distress among people” by ending the wheat subsidy before issuing electronic coupons for bread. Moeinoddin Saeidi, an independent lawmaker from Sistan and Baluchistan province, warned that Raisi’s “economic surgery… will lead to the death of the patient.”

Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a conservative and populist, also weighed in. “You [President Raisi] cannot do whatever you wish only because you are the boss!” he told a crowd in Bushehr in southern Iran. “The nation will not allow anyone to do anything against the people’s will.”

Major newspapers were divided. Some reformist dailies criticized the new policy while most conservative papers defended the government. The editor-in-chief of one conservative paper, however, called on Raisi to resign. “Now that it is clear that you cannot solve the problems, have the courage to step aside and leave the work to skilled people to save the people and the country from this vortex,” Masih Mohajeri wrote in a front-page op-ed for Jomhouri-e Eslami.

Problems with Multiple Exchange Rates

Many Iranian policymakers have long opted to use oil revenues to sustain the value of the rial. But the imposition of U.S. sanctions and subsequent decrease in oil revenues beginning in 2012 diminished the Central Bank’s ability to shore the up the currency. Subsequently, the gap between the free-market exchange rate and the official exchange rate widened. In response, the Central Bank decided to limit use of the subsidized exchange rate for the importation of essential goods.

Importers of essential goods—a list that was originally broad—could apply to the Central Bank for currency allocations far below the market rate. In theory, this helped keep key imports cheaper. But the Central Bank lacked the means to prevent Iran’s currency from being devalued, so the official rate remained low.

Over the years, importers reportedly received allocations of currency at the subsidized exchange rate only to turn around and sell the currency at rates closer to the free market rate. The system of multiple exchange rates allowed opportunities for corruption besides being an inefficient way for the Central Bank to manage the foreign exchange market.

Timeline of 2022 Protests

May 1: The government stopped allotting foreign currency below market exchange rates to importers of wheat, other basic foodstuffs, and some medicine. Within days, many retailers across the country tripled the price for flour-based products, including bread and pasta.

May 3: Seyyed Javad Sadatinejad, the Minister of Agriculture, blamed the price increases on the war in Ukraine, which disrupted the global food supply, and on smugglers trying to profit from selling wheat abroad.

May 6: Protests over the spike in bread prices broke out in the southwestern province of Khuzestan. In Izeh, residents reportedly seized a warehouse where flour was stored. In Sousangerd, security forces reportedly imposed a curfew and used live ammunition to disperse demonstrators. Reports were difficult to verify due to a disruption in internet connectivity.

Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a conservative and populist, criticized Raisi’s subsidy reforms. “You cannot do whatever you wish only because you are the boss!” he told a crowd in Bushehr, the capital of the southern province of Bushehr. “The nation will not allow anyone to do anything against the people’s will,” he warned.

May 7: At least 30 protestors had been arrested in Khuzestan province, the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) reported.

Mobile and landline internet in Khuzestan province had been throttled, and mobile internet from two major operators was cut off in some cities, Shargh, a reformist newspaper, reported. Disruptions were reported in Ahvaz, the provincial capital, as well as Abadan, Izeh, Hamidiyeh, and Sousangerd.

Masih Mohajeri, the editor-in-chief of the conservative daily Jomhouri-e Eslami, called on President Ebrahim Raisi to resign over the price increases. “Now that it is clear that you cannot solve the problems, have the courage to step aside and leave the work to skilled people to save the people and the country from this dangerous quagmire,” he wrote in a front-page op-ed. “If the instability of the government and the current dangerous situation have not been created by infiltrators, then they must be attributed to the poor management of your economic ministers.”

May 8: Security forces reportedly used tear gas to disperse protestors in Izeh and Sousangerd in Khuzestan province.

Mobile internet in Ahvaz, Hamidiyeh, Shadegan, and Sousangerd had been cut off since May 6, Jamaran News Agency reported. And landline internet was throttled.

May 9: Authorities reportedly raided the Tehran home of labor activists Anisha Assadollahi and Keyvan Mohtad and detained them.

A large contingent of security forces were deployed to Khuzestan province, according to the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI). “Iranian state forces used live ammunition and killed peaceful protesters in Khuzestan a year ago, and they appear to be gearing up for a bloody repeat,” warned Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of CHRI.

In a live televised interview, President Raisi explained his new economic reforms. He said that the government would distribute cash payments to most Iranians rather than indirectly subsidize the import of wheat and other necessities. Raisi also said that electronic coupons for subsidized bread would be issued in two months. The price of cooking oil quadrupled, and the prices of chicken and eggs doubled after the plans were announced.

May 10: Alireza Habibi, the manager of Radio Farhang, a state-run station, told staff to stop reporting on economic problems because they were “viewed as [national] security matters.” He instructed producers and presenters to not include “newspaper headlines that are gloomy, critical, or about high prices in the programs,” he said in an audio recording acquired by Iran International.

May 11: Protests continued in Khuzestan province, centered in the cities of Ahvaz, Dezful, Izeh, and Mahshahr. Protestors chanted anti-government slogans such as “Death to Raisi” and “Death to [Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali] Khamenei.” Some called for the return of the Pahlavi monarchy that was ousted in the 1979 revolution. “God bless your soul, Reza Shah,” some chanted.

NetBlocks, a cyber monitoring firm, reported a major disruption in internet connectivity. The slowdown “may limit the free flow of information amid protests,” it said.

⚠️ Confirmed: Real-time network data show a brief collapse in observable international connectivity on internet provider Rightel in #Iran, as well as a deterioration on other mobile and fixed-line providers; the slowdown may limit the free flow of information amid protests 📉 pic.twitter.com/uuzu2uYduB

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) May 11, 2022

Interior Minister Ahmad Vahidi denied reports about internet disruptions in Khuzestan province. “There is no area with insecurity in the country,” he said, according to Tasnim News Agency. Vahidi also pledged that no goods would become more expensive until the government’s subsidy plan is implemented.

May 12: The government cut subsidies on chicken, eggs, cooking oil, and milk. Prices jumped some 300 percent.

In a video, protestors in Kermanshah, the capital of the western province of Kermanshah, pulled down a billboard with a picture of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Security forces reportedly fired live rounds and wounded protestors in Khuzestan province. Omid Soltani, a 21-year-old, reportedly died after being shot in Andimeshk. Three days later, Ahmad Avaei, the area’s representative in Parliament, acknowledged that a resident of Andimeshk had been killed.

Major General Hossein Salami, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), acknowledged that the new government policies caused “difficulties.” He called on the Basij militia to help the people, “as the enemy is waiting for us to show weakness to take advantage.”

May 13: At night, demonstrators gathered in at least six provinces, in cities including Ahvaz and Dezful in the southwestern province of Khuzestan, Boroujerd in the western province of Lorestan, Qazvin in the northern province of Qazvin, and Shahr-e Kord in central Charmahal and Bakhtiari provinces. “Death to the dictator,” some chanted. In a video from Boroujerd, a man shouted “they are firing on the crowd.” State media reported that hundreds of people protested in cities across Iran.

Security forces reportedly shot Hamid Ghasempour, a protester in Farsan in Charmahal and Bakhtiari province. He later died at a hospital.

State media reported that at least 22 protestors had been arrested since the start of the protests. Police arrested “provocateurs” after they torched shops in some cities, according to IRNA.

First Vice President Mohammad Mokhber said that the increase in prices was not limited to Iran. “Prices in the world have changed... the situation in the region has created problems in the prices of products and the prices of basic goods were set accordingly.”

President Raisi spoke with residents of Tehran about the distribution of basic goods during visits to chicken and meat distribution centers and a supermarket.

May 14: Security forces reportedly fired on dozens of protestors who attacked a Basij militia base in the town of Babaheydar in the central provinces of Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari. Behrouz Eslami, a father of two, was reportedly shot and killed.

The Ministry of Intelligence banned local media from using particular words in reporting on the protests. The list included “clashing with people,” “sit-in”, “violent confrontation,” and “economic surgery,” according to Iran International. The latter was a term initially used by government officials to explain the economic reforms, but critics subsequently used the word in political cartoons and op-eds. Reporters Without Borders later said that authorities tried to intimidate journalists so that they would not cover the protests.

Ahmad Ahvaei, a member of parliament from Dezful, acknowledged that one person had been killed in Khuzestan province amid the protests.

Netblocks reported a significant drop in internet connectivity from MobinNet, one of the country’s largest wireless broadband providers, for 2.5 hours.

May 15: The United States supports the rights of Iranians to “peaceful assembly and freedom of expression online and offline - without fear of violence and reprisal,” State Department Spokesperson Ned Price tweeted.

Brave Iranian protestors are standing up for their rights. The Iranian people have a right to hold their government accountable. We support their rights to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression online and offline - without fear of violence and reprisal.

— Ned Price (@StateDeptSpox) May 15, 2022

Protests were held in at least 40 cities and towns, such as Quchan in northeastern Razavi Khorasan province, Rasht in northern Gilan province, and Hamadan in the western Hamadan province. Security forces deployed in Tehran in anticipation of demonstrations.

In a video posted to social media, protestors in Shahr-e Kord chanted “Death to Raisi.”

May 16: Said Madani, a professor of sociology at Allameh Tabatabai and a former political prisoner, had recently been detained, Mehr News Agency reported. Authorities alleged that he had “suspicious foreign connections” and was “acting against national security” in collaboration with “well known foreign elements.” He was taken into custody just hours after speaking to IranWire about the protests. Madani’s lawyer said that his client was held in solitary confinement in the infamous Evin Prison in Theran.

Vice President Mohammad Mokhber said that the price of chicken, eggs and cooking oil would “return to normal in the coming days.” He stressed that the price of bread should not have risen by “one rial.” Mokhber warned that infractions would not be tolerated.

Officials from the Intelligence Ministry and the Supreme National Security Council held two meetings with media executives to“to set policy on how to cover the protests and price reform plan,” an Iranian journalist told BBC Persian.

May 17: More than 500 Iranian civil and political activists urged officials to “exercise restraint” and to "think before it is too late to contain problems, especially staggering inflation.” The “unsettled and complicated’’ situation was the inevitable result of “the majority of the nation's elected officials not being approved by the people,” they said in a joint statement. The activists seemed to reference the Guardian Council’s power to vet candidates for public office.

Protestors chanted “Death to the dictator” and “Death to Raisi” in videos from Golpayegan in the central province of Isfahan.

Security forces reportedly used live ammunition to disperse protests in Jouneqan in southwestern Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari province. One demonstrator, Jamshid Mokhtari was hit with four bullets and died.

Demonstrations had spread to at least 20 cities, including Tehran, and at least five people had died, CHRI reported. “The Iranian people are in the streets to protest living costs and air grievances against their repressive government, and the Islamic Republic is responding yet again by killing and jailing them,” CHRI Executive Director Ghaemi said.

Amnesty International urged the international community to pressure Iran to stop using lethal force to disperse protestors. The human rights organization called for an independent U.N. mechanism to hold Tehran accountable. “It is the human right of people in Iran to organize and take part in peaceful protests free from intimidation, violence and threats of arbitrary arrest, torture and unjust prosecution.”

May 19: Video on social media showed riot police firing live ammunition at protestors in Farsan in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari province. In the cities of Shahr-e Kord and Hafshejan, in the same province, security forces fired teargas and used clubs to disperse demonstrators. In Dezful, in Khuzestan province, protestors chanted "Fear not, fear not, we are in this together."

Brigadier General Qasem Rezaee, the deputy commander of the police, warned the damage of public and private property would not be tolerated during demonstrations. “Police will act against those individuals with firmness.” He also said that authorities were cracking down on smuggling and hoarding of supplies, which exacerbated shortages.

May 20: Some 50,000 members of the IRGC and the Basij militia participated in a rally outside of Tehran to mark the 40th anniversary of the recapture of the city of Khorramshahr during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. “The enemies mistakenly think the Iranian people will respond to… the rumors that they spread and lies they tell,” IRGC commander Salami said in a reference to the protests.

May 21: President Raisi participated in an international forum on privatizing Iran’s economy. He warned that the government will be making “tough decisions that some may not agree with.” He did not elaborate.

Garrett Nada, managing editor of The Iran Primer, Tiffany Saade, a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson Center, and James Motamed, a research analyst at the U.S. Institute of Peace, contributed to this report.