After the 1979 revolution, the women’s movement in Iran faced challenges restoring rights they had recently gained under the monarchy, but over the next four decades they closed the gender gap in education, political representation and social rights. By 2020, women held more political rights in Iran than in neighboring Muslim countries, such as Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar. The movement went through four cycles:

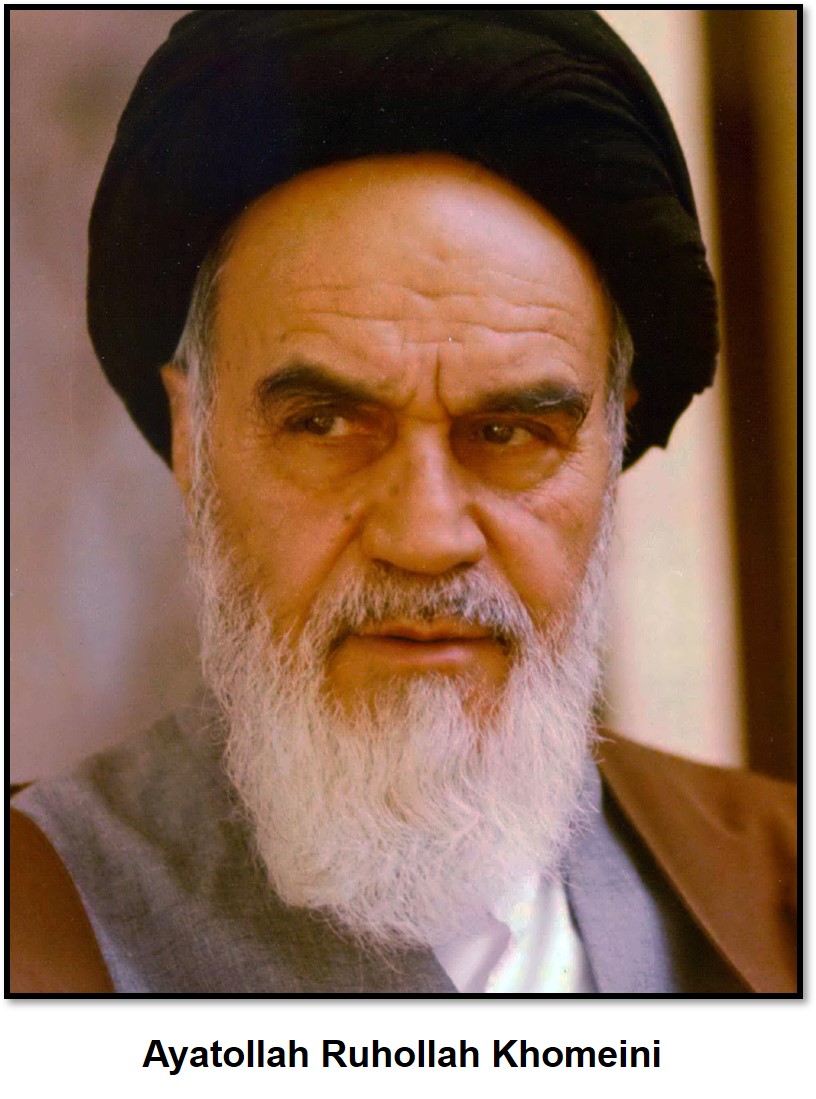

- Retrenchment during the first decade under Revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini,

- Hard-earned reforms under the presidencies of Presidents Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami,

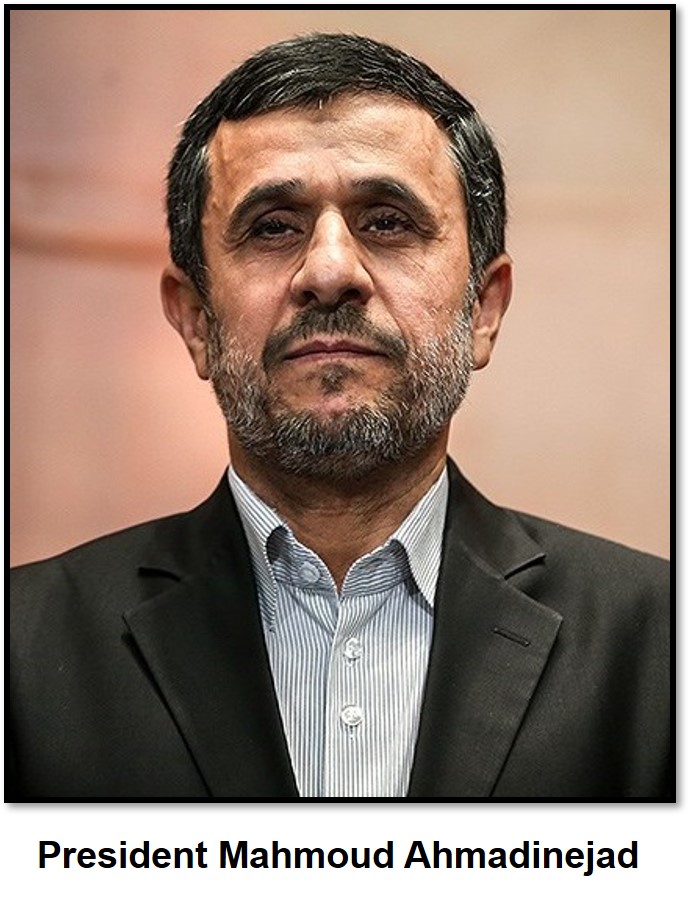

- Rollback under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad,

- Big promises but limited progress under President Hassan Rouhani.

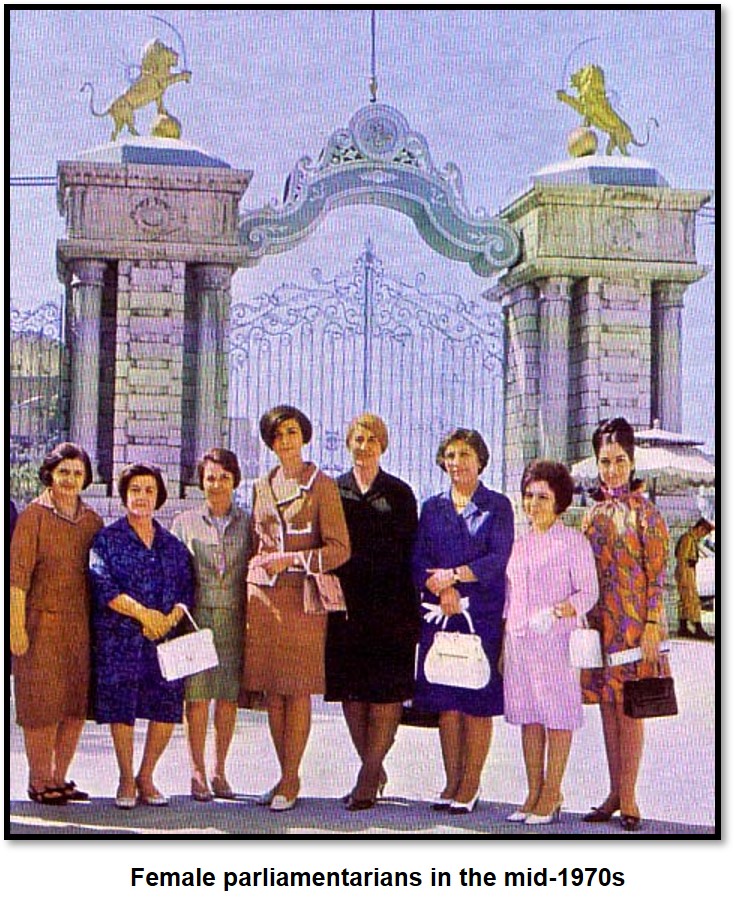

In 1963, the shah announced the first major political and social reforms to burnish his image with the West in the so-called White Revolution. Women were given the vote and allowed to run for political office. By 1978, on the eve of the revolution, women held 22 out of 268 seats in parliament, 333 served on local councils, and five were judges. Reforms allowed women to divorce their husbands and raised the legal age of marriage from 13 to 18 under the Family Protection Laws of 1967 and 1975.

Women’s rights were severely curtailed after the revolution, even though tens of thousands had taken to the streets to protest against the shah. The post-revolutionary constitution guaranteed “the rights of women in all respects, in conformity with Islamic criteria.” During the Khomeini decade, the theocratic government suspended the Family Protection Laws. It restricted social freedoms, such as the right to divorce. It lowered the age of marriage for women to nine, the age of puberty in Islamic law. (The age of marriage for men was lowered from 18 to 15). It also mandated wearing the head scarf, the hijab. Violators faced harsh punishment, including flogging and jail time. Women, however, retained many political rights, including the right to vote and to run for parliament.

Women’s rights were severely curtailed after the revolution, even though tens of thousands had taken to the streets to protest against the shah. The post-revolutionary constitution guaranteed “the rights of women in all respects, in conformity with Islamic criteria.” During the Khomeini decade, the theocratic government suspended the Family Protection Laws. It restricted social freedoms, such as the right to divorce. It lowered the age of marriage for women to nine, the age of puberty in Islamic law. (The age of marriage for men was lowered from 18 to 15). It also mandated wearing the head scarf, the hijab. Violators faced harsh punishment, including flogging and jail time. Women, however, retained many political rights, including the right to vote and to run for parliament.

The greatest gains were made in education. In 1998, Iran won the U.N. award for closing the gender gap in education. By 2016, 97 percent of 15 to 24 years old women were literate, compared to 98 percent of men. Overall, 81 percent of women were literate, compared with 90 percent of man. Females accounted for 60 percent of students at Iranian universities. Women also became more visible in domestic politics. They actively campaigned for presidents who eased social restrictions on women, won appointments to executive positions, and ran for political office themselves.

Gender inequality, however, persisted. As of 2020, women comprised only 15.2 percent of the workforce and held only 6 percent of seats in parliament. Married women faced inadequate protection from domestic violence at home and could not travel outside the country without their husband’s permission. Activists who protested were imprisoned; some even committed suicide to avoid harsh punishment. Like Iran itself, the women’s movement is complex, said Sussan Tahmasebi, a prominent women’s rights activist. “The situation of women in Iran is not as simple as what people hear outside of the country.”

More in this series:

- Part 2: Profiles of Women Politicians, Activists

- Part 3: Iranian Laws on Women

- Part 4: Khomeini and Khamenei on Women

- Part 5: Statistics on Women in Iran

Retrenchment (1979-1989)

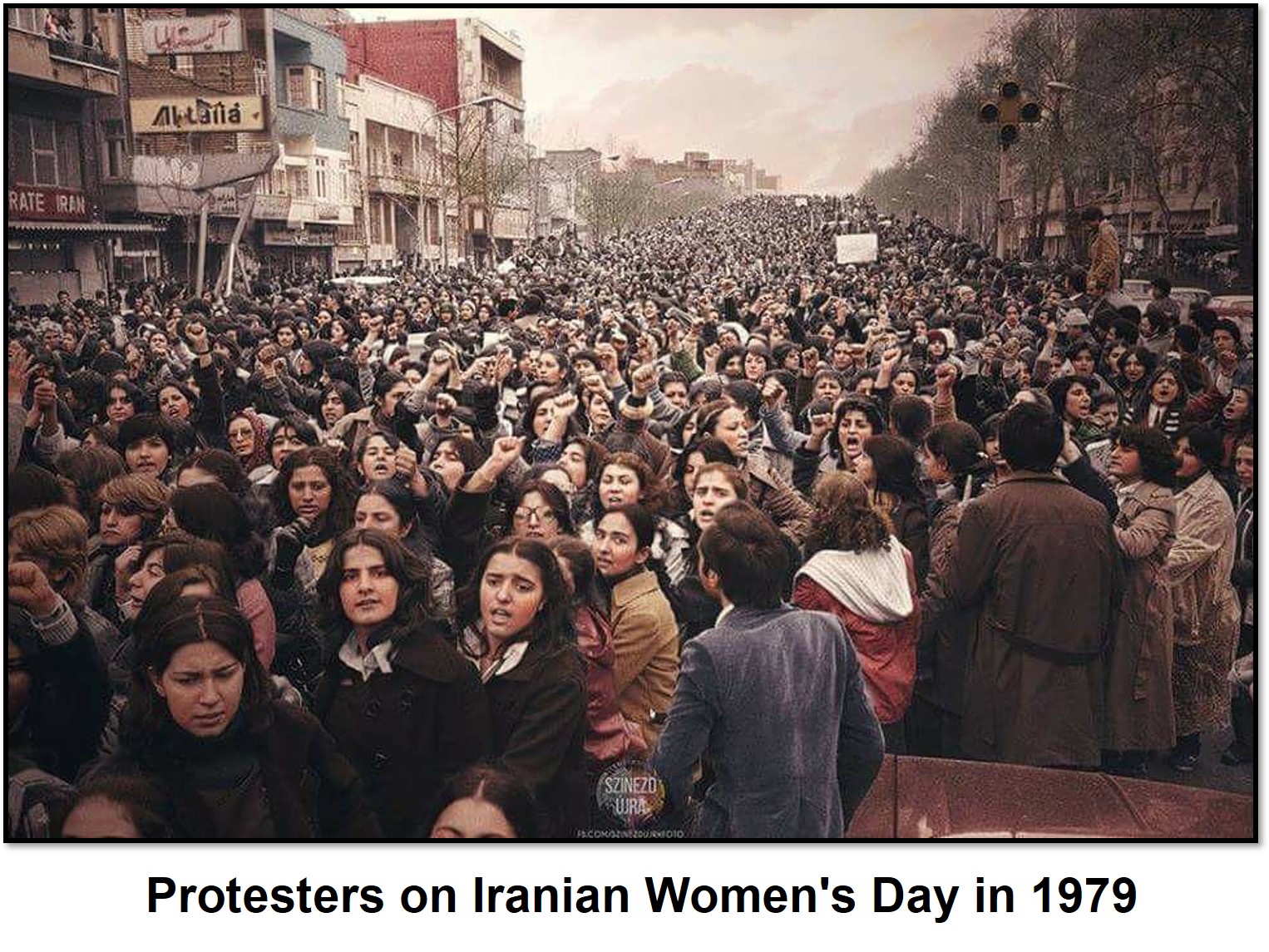

Women participated in the revolution, but their role in society was hotly debated during the 16-month transition as the revolutionaries defined a new political system. Women were caught in the political crossfire between religious conservatives and secular liberals who increasingly split after ousting the monarchy. In March 1979, thousands of women protested Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s mandate that all women wear the black chador, a full-body religious covering, or roupoosh, shapeless full-length coats. Dress became a rallying cry for revolutionary factions that opposed religious rule, including the Communist Tudeh Party, the Marxist Mujahdeen-e Khalq and the secular National Democratic Front. Besides strict dress codes, women also demanded equal civil rights and an end to discrimination in politics, society and the economy. “In the dawn of freedom, there is an absence of freedom,” marchers chanted in front of the Palace of Justice on March 11, 1979.

Not all women opposed a religious agenda. Many women from traditional families had long worn chadors; many believed the revolution belonged to the rural poor and dispossessed. The political fight over the dress code sharply divided secular and religious woman. “Everyone in my family is equal to everyone else in my family,” Soghra All Pour, a rural mother of six, told The New York Times in April 1979. “We eat the same thing, and we work the same. I ask you, where is this not balanced?”

Not all women opposed a religious agenda. Many women from traditional families had long worn chadors; many believed the revolution belonged to the rural poor and dispossessed. The political fight over the dress code sharply divided secular and religious woman. “Everyone in my family is equal to everyone else in my family,” Soghra All Pour, a rural mother of six, told The New York Times in April 1979. “We eat the same thing, and we work the same. I ask you, where is this not balanced?”

On April 2, 1979, Khomeini proclaimed a “government of God”- two days after a national referendum on whether Iran should become an Islamic Republic. The transition to an Islamic state led many traditional families to allow their daughters to be educated beyond elementary school, partly because classes were newly segregated by gender. “If there was no gender segregation at the K to 12 level, many families wouldn’t send their children to school,” said Dr. Fatehmeh Haghighatjoo, a reformist member of parliament from 2000 to 2004. “I do not support gender segregation, but for traditional society that really helped.”

Under Khomeini, the theocracy consolidated power in a new constitution. In 1980, the new Islamic Republican Party then won the first parliamentary elections. Both undermined early attempts by liberal groups to secure women’s rights. The regime moved swiftly to impose a rigid vision of Islamic governance. It nullified the Family Protection Laws and lowered the age of marriage from 18 to 13, before reducing it further to nine. It segregated schools by gender. Women lost the right to divorce and to child custody. Men were permitted to marry a second wife without his first wife’s consent—or knowledge. In court, a woman’s testimony counted only half of a man’s. The Islamic Law of Retribution, passed in 1981, punished female adulterers with death by stoning.

Under Khomeini, the theocracy consolidated power in a new constitution. In 1980, the new Islamic Republican Party then won the first parliamentary elections. Both undermined early attempts by liberal groups to secure women’s rights. The regime moved swiftly to impose a rigid vision of Islamic governance. It nullified the Family Protection Laws and lowered the age of marriage from 18 to 13, before reducing it further to nine. It segregated schools by gender. Women lost the right to divorce and to child custody. Men were permitted to marry a second wife without his first wife’s consent—or knowledge. In court, a woman’s testimony counted only half of a man’s. The Islamic Law of Retribution, passed in 1981, punished female adulterers with death by stoning.

In the judiciary, women were barred from serving as judges, and senior clerics urged women to be prohibited from graduating from law school. They could not serve in top religious positions, including supreme leader, and all female candidates were disqualified from running for president by the Guardian Council – an all-male body of 12 Islamic scholars and jurists. The constitution made families “the fundamental unit of society,” and clerics urged women to breed an “Islamic generation.” It also promoted “the protection of mothers,” particularly during pregnancy and childrearing, and the “rearing of ideologically committed human beings.” In practice, many women were pushed out of the work force. The Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) led the government to employ women as medics, but women’s overall participation in the workforce still dropped from 13 percent during the shah’s final year to 8.6 percent during the first decade of the revolution.

Reform (1989-2004)

The end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988 and Khomeini’s abrupt death in June 1989 marked the beginning of a new political era, including for women. Female voters were a pivotal bloc during the 1989 presidential elections that brought Rafsanjani to office and reelected him in 1993. Rafsanjani was a wily pragmatist. Iranian voters overwhelmingly backed his call for incremental reform within the constraints of Islamic law. "Islam and the Revolution have envisioned far greater opportunities for women,” he told a crowd of 80,000 at Azadi Stadium in November 1994.

During his presidency, from 1989 to 1997, Rafsanjani’s government eased social restrictions on women. New reforms allowed women to initiate divorce proceedings and lifted restrictions on female employment in engineering and legal work. Women won four-month compulsory maternity leave, passage of an equal opportunity labor law, reduced punishments for improper dress and the right to an abortion when the life of a woman was threatened. In 1989, Iran introduced a encouraged family planning, which included free contraceptives, that brought the population growth rate down from 3.9 percent in 1985 to 2.7 percent in 1992. One of the program’s selling points was that women would have a better life with fewer children.

In the 1990s, women were more visible in the legislature and the executive branch. Dozens ran for parliament in April 1992; they won 13 out of 270 seats. In 1996, a woman was selected as mayor of a Tehran district. By 1994, 30 percent of government employees were female. Rafsanjani appointed Shahla Habibi as an advisor on women's affairs. During his second term, he appointed a female deputy minister. Still, women could not serve as judges, divorce their husbands at will, or freely marry without the consent of a male guardian.

In the 1990s, women were more visible in the legislature and the executive branch. Dozens ran for parliament in April 1992; they won 13 out of 270 seats. In 1996, a woman was selected as mayor of a Tehran district. By 1994, 30 percent of government employees were female. Rafsanjani appointed Shahla Habibi as an advisor on women's affairs. During his second term, he appointed a female deputy minister. Still, women could not serve as judges, divorce their husbands at will, or freely marry without the consent of a male guardian.

In 1997, the election of President Mohammad Khatami, a reformist, accelerated progress. Khatami and his allies in parliament passed laws granting greater legal rights in divorce proceedings and improved access to higher education. In 2002, the Majles also raised the age of marriage to 13. “The reform movement was a better era for the flourishing of women’s rights,” Haghighatjoo said. “We never had any other parliament like the sixth parliament (2000-2004) in terms of supporting women’s rights.”

Under Khatami, women also dramatically increased their presence in education and the workforce. From 1990 to 2000, the number of women entering university tripled. In 2003, Khatami congratulated Shirin Ebadi, a human rights lawyer, for becoming the first Muslim woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Under Khatami, women also dramatically increased their presence in education and the workforce. From 1990 to 2000, the number of women entering university tripled. In 2003, Khatami congratulated Shirin Ebadi, a human rights lawyer, for becoming the first Muslim woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Khatami also brought women into senior government positions for the first time. In 1997, he appointed Masoumeh Ebtekar as vice president for the environment as well as a record number of women to senior government positions. "We should have a comprehensive view of the role of women and before anything else, should not regard women as second-class citizens," Khatami said in 2005. "We should all believe that both men and women have the capability to be active in all fields, and I emphasize, in all fields."

Rollback (2004-2013)

During his final year in office, Khatami faced opposition to further reforms for women after hardliners and conservatives won the majority of seats in the 2004 parliamentary elections. The new Majles rejected a proposal to expand inheritance rights and to use gender equality as a benchmark for economic development. Days before the 2005 presidential election, hundreds of women protested sex discrimination during the campaign pitting Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a hardline newcomer, against former President Rafsanjani. “We are women. We are the children of this land,” they chanted. “But we have no rights.”

Ahmadinejad’s victory solidified conservative and hardline control over the third of the three branches of government – executive, legislative and judicial—which led to the rollback of women’s rights. Ahmadinejad pushed “Islamification” measures at major universities, such as banning women from majoring in computer science, engineering, political science, accounting, business and public administration. His government also eliminated the budget for Rafsanjani’s family planning measures and offered families financial incentives to have children.

Ahmadinejad’s victory solidified conservative and hardline control over the third of the three branches of government – executive, legislative and judicial—which led to the rollback of women’s rights. Ahmadinejad pushed “Islamification” measures at major universities, such as banning women from majoring in computer science, engineering, political science, accounting, business and public administration. His government also eliminated the budget for Rafsanjani’s family planning measures and offered families financial incentives to have children.

During Ahmadinejad’s presidency, the independent judiciary also cracked down on female activists. In 2006, police arrested dozens of women who signed the One Million Signatures petition calling for equal rights in marriage, divorce, custody and inheritance law. The regime escalated the crackdown in 2008 when they detained Sussan Tahmasebi, the leader of the petition movement. Many Iranians were not aware of the scope of discrimination in the law when the One Million Signatures Campaign began, Tahmasebi said. Part of the challenge was just making them aware of the legal codes.

Four women activists were also arrested for writing articles on feminist websites; they were sentenced to six months in jail. The government shut down Zanan, Iran’s leading feminist magazine, after charging it with being a “threat to the psychological security of the society.”

Under Ahmadinejad, women’s representation in politics decreased, partly because of the conservative influence in parliament. Ahmadinejad attempted to nominate three women to his cabinet, but only one was confirmed– Marzieh-Vahid Dastjerdi –as minister of health. In the 2008 parliamentary election, only nine women—out of 585 female candidates—were elected, down from 13 seats in 2004. All the winners were conservative or independents.

Limited progress (2013-2020)

Female activists had high expectations when President Hassan Rouhani assumed office in August 2013. Rouhani ran as a centrist promising reform. He did not explicitly campaign on women’s rights, but many female voters backed his agenda and believed he would govern in the mold of Rafsanjani and Khatami. “The women of Iran voted for President Rouhani, and they will be keeping a close eye on the actions of his administration on women’s issues,” Mehrangiz Kar, a human rights lawyer, wrote in October 2013.

Rouhani increased female representation in government and the workforce. In his first term, he appointed four female vice presidents and three female governors at the district and county level. His government drafted reforms to increase women’s participation in high-level management positions and investigated sex discrimination in the job market. "Women must enjoy equal opportunity, equal protection and equal social rights," Rouhani said on Women’s Day in April 2014. In the 2016 parliamentary elections, women won 17 seats, the highest number since the revolution.

Rouhani increased female representation in government and the workforce. In his first term, he appointed four female vice presidents and three female governors at the district and county level. His government drafted reforms to increase women’s participation in high-level management positions and investigated sex discrimination in the job market. "Women must enjoy equal opportunity, equal protection and equal social rights," Rouhani said on Women’s Day in April 2014. In the 2016 parliamentary elections, women won 17 seats, the highest number since the revolution.

Yet female activists criticized Rouhani for appointing no women to his cabinet. After winning reelection in 2017, he appointed women to three high profile positions: Masoumeh Ebtekar as vice president for family and women’s affairs, Laya Joneydi as vice president for legal affairs, and Shahindokht Molaverdi as presidential assistant for civil rights. But he again failed to appoint a woman to his cabinet.

Under Rouhani, women won several legal victories. In 2019, parliament passed – and the hardline Guardian Council approved -- a law allowing women to pass on their citizenship to children of foreign spouses. In October 2019, thousands of women were allowed to attend an international soccer match in Tehran for the first time in nearly four decades; the change was allowed only for FIFA matches, not local games. But the ruling followed the widely covered suicide of Sahar Khodayari, 22, after she was arrested for attending a soccer match. She set herself on fire after she was sentenced to prison term of six months to two years.

But broader efforts – to prevent violence against women, amend personal status law and ban honor killings – stalled due to hardline opposition. “For Rouhani, having an international deal on Iran’s nuclear program was his main point, and he didn’t want to aggravate religious people in the government,” Haghighatjoo said. “Still, this is not a good excuse from my point of view.”

But broader efforts – to prevent violence against women, amend personal status law and ban honor killings – stalled due to hardline opposition. “For Rouhani, having an international deal on Iran’s nuclear program was his main point, and he didn’t want to aggravate religious people in the government,” Haghighatjoo said. “Still, this is not a good excuse from my point of view.”

The judiciary continued to crackdown on female activists, despite Rouhani’s promise of reforms. “He’s either been completely unable or completely unwilling to address this persecution of women’s rights activists,” said Karen Kramer, publications director at the Center for Human Rights in Iran, which is based in New York. In May 2017, women launched the white scarf moment by removing their headscarves in public places and waving them on a stick to protest strict state dress codes. Many were arrested and charged with various crimes, including,

- assembly and collusion acts against national security

- propaganda against the state

- encouraging moral corruption and prostitution.

Young activists – including Monireh Arabshahi, Yasaman Aryhani and Mojgan Keshavarz - faced sentences from five to 15 years. The judiciary also targeted prominent human rights lawyers who defended the activists. The judiciary is trying to “punish lawyers or to threaten lawyers not to accept women’s rights or political cases,” Haghighatjoo said. The campaign intensified during Rouhani’s second term (2017-2021).

Nasrin Sotoudeh– a Tehran lawyer, who represented activists, victims of domestic abuse and journalists – was sentenced to 38 years. Other female human rights lawyers– including Hoda Amid, Zeinab Taheri, and Soheila Hejab – were also charged. “The length of years is astonishing,” Tahmasebi said. “The amount of money being demanded for bail is astonishing, given the economic situation of the country.”