Since taking office in August 2013, President Hassan Rouhani has failed to deliver on promises to open up Iran politically, ease rigid social restrictions and address human rights abuses. Execution rates have steadily increased over the past decade. Political dissidents and journalists are often denied due process or imprisoned for vaguely-defined criminal charges, including “enmity towards God,” “corruption on earth,” and acts undermining state security. Minorities face discrimination in education, employment and property ownership. Laws are often ignored to quash opposition. Even juveniles are vulnerable to abuses.

In a 2016

report, U.N. Special Rapporteur for Iran Ahmed Shaheed said that many provisions of Tehran’s Islamic penal code “facilitate serious abuses” and criminalize the peaceful exercise of fundamental rights. Iran had at least

821 political prisoners or prisoners of conscience in March 2016, according to the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center.

Rouhani’s authority to enact large scale social or cultural change has been limited. Hardliners dominate the judiciary, intelligence agencies and security services. The president also does not appoint judges. But Rouhani does have the power to investigate state institutions that violate constitutional rights, according to the

International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

Mohammad Khatami faced similar obstacles during his presidency between 1997 and 2005. He also had an ambitious agenda to open up Iranian society. Yet in 1999, he was largely

passive when security forces cracked down on student protests at Tehran University. Hardliners repeatedly undermined Khatami, despite strong support for his policies among reformers who dominated Parliament from 2000 to 2004. He was unable to stop the arrest of activists and intellectuals or prevent the closure of reformist publications. Compared to Khatami, Rouhani is at a deeper disadvantage because his supporters have never been a decisive faction in the legislature.

With a presidential election due in mid-2017, Rouhani’s shortcomings on human rights may face greater public scrutiny. Iran’s record also jeopardizes Rouhani’s attempts to improve relations with the international community. The Islamic Republic is still sanctioned by the United States for human rights abuses.

Death Penalty

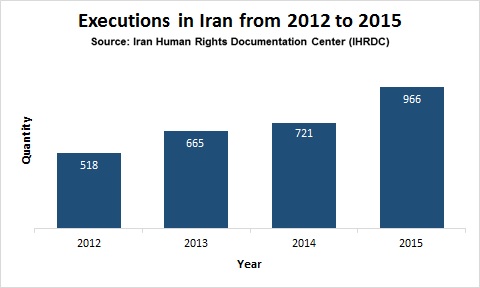

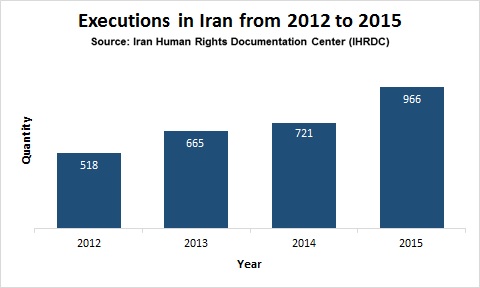

In 2016, the U.N. reported that capital punishment in the Islamic Republic “continues to surge at a staggering rage.” It increased under both President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Rouhani. In 2015, Iran carried out an average of four executions per day between April and June. The Iran Human Rights Documentation Center

reported 195 executions in the first five months of 2016.

The death penalty is most often invoked for drug-related crimes and other ill-defined violations, such as

Moharebeh, or, “enmity against God.” The U.N. reported that 65 percent of executions in 2015 were drug-related, although Iran claimed 80 percent of the country’s total executions were linked to narcotics. In May 2016, Mohammad Javad Larijani, Secretary of Iran’s Human Rights Council, claimed that Iran was reconsidering the death penalty for narcotics convictions. “We need to have a [better]

method to fight against drugs,” he

said.

The State Department has faulted Iran for executing juveniles and due process violations in capital punishment cases. Iranian law permits the execution of girls as young as nine and boys age 13—the age of puberty—if the accused understands the consequences of his or her crime. In 2015, authorities

reportedly executed four people who were charged with crimes committed when they were under 18 years old. In 2016,

Human Rights Watch identified 49 juveniles thought to be on death row. The United Nations suspected the

number could be as a high as 160.

In August 2016, authorities announced the execution of 20 men who were allegedly members of a terrorist group called “Jihad and Towhid.” They were convicted of establishing a terrorist group and killing a Friday prayer leader and several guards. But two lawyers who represented some of the men told Human Rights Watch that their clients did not get a fair trial and that their due process rights had been violated.

Iran has overturned a few death sentences. In February 2016, for example, Iran’s Supreme Court reversed Mohammad Ali Taheri’s death sentence. Taheri, founder of the spiritual practice “Interuniversalism,” has been in solitary confinement for five years on charges of “

insulting Islamic sanctities.”

Political Dissent

During his 2013 campaign, Rouhani Tweeted:

As of mid-2016, however, the government still heavily restricted the freedoms of expression, association, and assembly. Authorities frequently arrested students, journalists, lawyers, political activists, women’s activists, artists, and religious minorities. The government also “arrested, convicted, and executed persons on criminal charges, such as drug trafficking, when their actual offenses were political,” according to the State Department.

According to Amnesty International’s 2015

report, “Scores of prisoners of conscience continued to be detained or were serving prison sentences for peacefully exercising their human rights.” Monitoring groups noted an uptick in arrests of journalists, artists, and activists in the run-up to the 2016 Parliamentary and Assembly of Experts elections. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran described the

arrests in late 2015 and preceding months as a “visible expression of the crackdown.”

In 2015, prison conditions were “often harsh and life-threatening,”

according to the State Department. “Some prison facilities...were notorious for the use of cruel and prolonged torture of political opponents of the government,” it reported in 2015. Quarters were severely overcrowded, and

reports cited incidences of prisoner suicide. Political prisoners were vulnerable to attacks by other inmates.

Prisoners are also often denied critical medical treatment. In 2011, authorities

arrested postdoctoral student Omid Kokabee on charges of illegal earnings and “communicating with a hostile government.” Kokabee showed signs of severe kidney illness in Evin prison, but he did not receive prompt treatment. Diagnosed with cancer, his right kidney was surgically removed in April 2016.

Amendments to the new

Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) came into effect in June 2015,

according to the U.N. special rapporteur. The code affords those suspected of crimes greater protection. However, the law still has some problems that need to be resolved,

according to the National Union of Bar Associations of Iran.

Women

“In the future cabinet, in all social areas, discrimination among men and women will be eliminated,” Rouhani pledged in mid-2013. He promised to uphold women’s rights and sponsor legislation addressing gender discrimination. As of mid-2016, however, Iran’s laws significantly favored men as much as before Rouhani’s election.

In the early months of his presidency, Rouhani secured the release of seven women activists and human rights lawyer Nasrine Sotoudeh from prison, according to

Haleh Esfandiari, director emerita of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The president also appointed four women vice presidents and three governors. He instructed his cabinet members to appoint women as deputy ministers. He did not, however, assign women to his cabinet or revive the Ministry for Women’s Affairs as he had promised.

Women’s political participation increased in 2016 during the parliamentary election. A record number of women, 1,434, registered to run. And a

record 17 women won seats, although after the election, the Guardian Council disqualified

Minoo Khaleghi. For the first time, women outnumber clerics in the Majles (Parliament).

But women still face serious discrimination, especially in matters related to marriage, divorce, inheritance and child custody. In 2012, the government initiated efforts to reverse Iran’s population decline. Minister of Health and Medical Education Marzieh Vahid Dastjerdi

announced a

cut back on funding for the family planning program.

Women are obligated to wear appropriate hijab--including head covering and modest Islamic dress— although it lacks a clear legal definition. Females can receive floggings or steep fines for violations,

according to the State Department. Opponents of the dress code have used

social media to criticize and flaunt the laws, but no changes have been made.

The morality police, who answer to the supreme leader, monitor the streets of Iran for violations of the Islamic dress code. In April 2016, Iran’s

morality police added thousands of undercover plainclothes police to track women with poor hijab. Rouhani

criticized the practice. “Our first duty is to respect people’s dignity and personality. God has bestowed dignity on all human beings and this dignity precedes religion,” he said.

Women’s rights are also curtailed in marriage. The law considers intercourse within marriage consensual, allowing for spousal rape. A husband is not required to cite a reason for divorcing his wife. A wife, however, is limited to specific justifications in order to divorce her husband. Women may not transmit citizenship to their children or to non-Muslim spouses, according to the State Department’s 2015

report.

In early June 2016, professor of social anthropology Homa Hoodfar was arrested and taken to Evin Prison for

allegedly “co-operating with a foreign state against the Islamic Republic of Iran.” Hoodfar, a professor at Concordia University in Montreal and a dual citizen of Iran and Canada, was “conducting historical and ethnographic research on women’s public role,” according to her

family. The 65-year-old scholar traveled to Iran in February 2016 primarily for personal reasons, but also to conduct academic research. She was imprisoned following nearly three months of questioning by Iran’s intelligence service, her sister told

The Guardian.

Religious Minorities

“All Iranian people should feel there is justice. Justice means equal opportunity. All ethnicities, all religions, even religious minorities, must feel justice,” Rouhani

said during his 2013 presidential campaign.

Shiite Muslims constitute some 90 percent of Iran’s population, with Sunni Muslims being the next largest group at about nine percent, according to U.S. government

estimates. The Islamic Republic’s constitution recognizes Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians as minorities and allocates a total of five seats for them in Parliament, proportionate to their populations. But

minorities risk

charges of

Moharebeh, “anti-Islamic propaganda,” or threatening national security. They also face religious discrimination in property ownership, education, and employment.

In 2012, Rev. Saeed Abedini was arrested for organizing Christian churches in Iranian homes. He was charged with attempting to undermine the Iranian government and

reportedly endured torture and beatings during his imprisonment. Iran released Abedini, in January 2016 as part of a prisoner swap with the United States.

The Baha’i, Iran’s largest non-Muslim religious minority, are not protected under the law and cannot practice their faith openly. The government views Baha’is as “

heretics.” As of February 2016, at least 80 Baha’is were

imprisoned for their religious beliefs.

In May 2016, the State Department

condemned Iran for continuing to imprison seven Baha’i community leaders eight years after their arrest. Spokesperson John Kirby called on Iranian authorities to “uphold their own laws and meet their international obligations that guarantee freedom of expression, religion, opinion, and assembly for all citizens.”

The Iranian government maintains that it allows Baha’is to obtain higher education, but Baha’i students find it difficult to in practice, according to a

2016 report by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. In 2015 and 2016, Baha’i youth with high standardized test scores were denied entry to or expelled from schools after their religious identities were discovered.

In November 2015, agents from Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence

arrested at least 15 Baha’is. The reason for the arrests was unknown. In April and May of 2016, authorities

closed 35 Baha’i-owned shops to allegedly prevent Baha’i holy day observances.

Ethnic Minorities

Persians make up the majority of the population, but Iran is also home to several ethnic minorities. The largest groups

are the Azeris, Kurds, Lors, Arabs, and Baluchis, who face significant cultural and political restrictions.

Iran’s eight million Kurds still face discrimination. Several were persecuted and arrested after the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK)

campaigned for regional autonomy in 2015. Others have been arrested for working in Kurdish non-government organizations. Kurds were long banned from registering Kurdish names for their children or teaching the Kurdish language in most schools. In July 2015, however, the University of Kurdistan announced its opening of a Kurdish language and literature program, according to a Human Rights Watch

report. And in September 2015, Rouhani

appointed a Sunni Kurd, Dr. Saleh Adibi, to be ambassador to Vietnam and Cambodia. Dr. Adibi is widely

thought to be the first Iranian Sunni to be appointed as a

senior envoy since the 1979 revolution.

Azeris are the largest ethnic minority and account for about 16 percent of the population – around 13 million people. They are well-integrated into Iranian society. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is reportedly half

Azeri, although his official bio does not mention an Azeri heritage. In 2015, however, the State Department

reported that the government harassed Azeri activists, prohibited the Azeri language in schools, and changed Azeri town names.

Arabs account for about two percent of Iran’s population, more than 1.5 million people, according to U.S.

estimates. Rouhani appointed

Ali Shamkhani — an Arab and a former defense minister — as Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council in 2013. But the U.N. special rapporteur reported in August 2015 that authorities arrested approximately 1,000 demonstrators in March 2015 for protesting on behalf of Younes Asakere, an Arab who set himself on fire after harassment by local authorities. In 2016, security forces singled out Ahwazi Arabs — Arabs from Ahwaz, Khuzestan province — as well as Azeris and Kurds, according to

Amnesty International. In April 2016, security forces

detained scores of Ahwazi Arabs, including several children.

Iran’s Baluchis number more than 1.5 million people and live in areas that have historically been underdeveloped. Baluchis, who are Sunni, also live in Pakistan and Afghanistan. In Iran, Baluchis had limited access to education, healthcare, shelter, and work in 2015 according to a

report by the State Department. Baluchis have also been underrepresented in government positions.

Artists

In April 2014, President Rouhani Tweeted:

Artists and filmmakers faced

censorship before Rouhani’s election in 2013, and little has changed since then.

More bands have been permitted to perform concerts since Rouhani took office, but local authorities — who are often

ultra-conservative — still consider music, singing, and dancing

haram, or sinful. For example, in May 2016, local authorities in the city of Nishapur

cancelled at least three performances by famous Iranian musicians.

Two

poets, Fatemeh Ekhtesari and Mehdi Mousavi, received sentences of 11 and nine years in prison, in addition to 99 lashes for “insulting sanctities,” according to the Freedom House’s 2016 report. In January 2016, both poets

escaped Iran.

Journalists

Since his 2013 campaign, Rouhani has repeatedly called for more press freedom. “We also need a clear law for press and media, thus, as far as the law is clear and unambiguous, no one can stick to a part of it and play with or misuse people's rights of freedom of press in the society,” he said in November 2015. Freedom House

reported in 2016 that “some journalists and citizens say the situation improved slightly after Rouhani took office.” During his campaign, Rouhani promised to reinstate the Association of Iranian Journalists but has not done so, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Hardliners have continued to crack down on journalists, artists, and activists in waves of arrests, according to

Amnesty International. Iran ranked 169th out of 180 countries in the World Press 2016

freedom index. Journalists’ families also experience harassment, and some imprisoned journalists were kept in solitary confinement.

In April 2016, an Iranian revolutionary court imposed prison sentences on four pro-Rouhani journalists. All of them worked for reformist newspapers and were

charged with assisting the United States in “infiltrating” Iran. Human Rights Watch

described their charges as “overly broad” and “inconsistent with human rights law.”

Jason Rezaian, an Iranian-American and correspondent for

The Washington Post, was one of the most prominent cases during Rouhani’s presidency

. He was detained on

charges that included espionage. He was sentenced to a prison term of unspecified length after a closed-door trial, according to

Freedom House. Rezaian was released in January 2016 as part of a prisoner exchange between the United States and Iran.

In June 2016, artist and activist Atena Farghadani was sentenced to more than 12 years in prison for a political cartoon that depicted Iran’s members of parliament as animals. She stated that authorities forced her to take a virginity test after shaking hands with her male lawyer, according to the State Department.

Citizens’ Rights Charter

During his 2013 campaign, Rouhani promised a new “civil rights charter.” His administration published a draft in November 2013, but progress has been stalled. In theory, it would guarantee all Iranians citizenship rights regardless of gender, ethnicity, wealth, social class, and race. It would define citizenship rights, the government’s obligations, and penalties for violations.

The

draft divided “The Most Important Citizenship Rights” into 21 sections including “Life, Health, and Decent Living,” “Freedom of Opinion, Expression, and Press,” and “Administrative Health, Proper Governance, and Rule of Law.” It also contained a vague “Minorities and Ethnic Groups” section; another entitled “Combating Narcotics” described the government’s responsibility to create a drug-free environment.

According to Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, the draft

identifies rights violators, recognizes the security environment’s degrading effect on rights, and gives the Iranian media a discussion platform. But “the draft Charter suffers from serious shortcomings, both in terms of its unclear legal status within the Iranian legal system and in the actual content of the Charter itself,” he

wrote. Lawyer and human rights activist Mehrangiz Kar

compared the draft to a “slogan” that lacked realistic enforcement power and planning.

Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said in April 2016 that Rouhani may want to put aspects of the draft to a vote in Parliament. “The Citizens’ Bill of Rights does not require parliamentary approval,” he told

The New Yorker. But the president may want to “put in place certain procedures and guarantees and mechanisms,” which may require parliamentary approval.

Lisa Canak is a cadet at West Point who completed her Academic Individual Advanced Development training at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

In a 2016 report, U.N. Special Rapporteur for Iran Ahmed Shaheed said that many provisions of Tehran’s Islamic penal code “facilitate serious abuses” and criminalize the peaceful exercise of fundamental rights. Iran had at least 821 political prisoners or prisoners of conscience in March 2016, according to the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center.

In a 2016 report, U.N. Special Rapporteur for Iran Ahmed Shaheed said that many provisions of Tehran’s Islamic penal code “facilitate serious abuses” and criminalize the peaceful exercise of fundamental rights. Iran had at least 821 political prisoners or prisoners of conscience in March 2016, according to the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center.