On September 10, President Hassan Rouhani appointed former Defense Minister Ali Shamkhani as the new secretary of the Supreme National Security Council -- effectively making him national security advisor. Shamkhani, a centrist, will replace hardliner Saeed Jalili, who was chief negotiator in talks on Iran’s controversial program between 2007 and 2013. Rouhani recently announced that the foreign ministry will lead future nuclear talks, so Shamkhani’s role will differ from his predecessor’s.

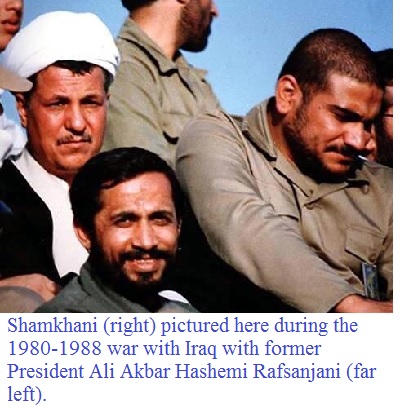

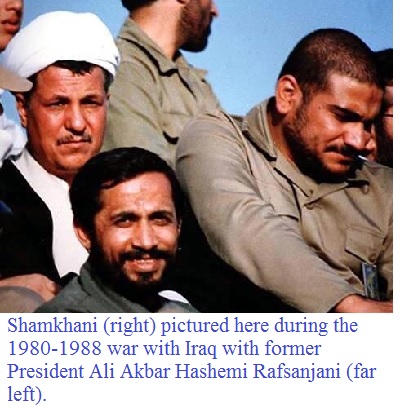

Born in 1955, Shamkhani is an Arab from Ahvaz near the Iraqi border. He commanded the Revolutionary Guards Navy during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. Shamkhani served as defense minister under reformist President Mohammad Khatami between 1997 and 2005. As defense minister, he played a leading role in improving relations between Iran and Persian Gulf sheikhdoms. In 2004, Shamkhani received Saudi Arabia’s highest medal, the Order of Abdulaziz al Saud, from King Fahd for his efforts. Shamkhani directed the Iranian Armed Forces’ Center for Strategic Studies from 2005 until his appointment by Rouhani.

Born in 1955, Shamkhani is an Arab from Ahvaz near the Iraqi border. He commanded the Revolutionary Guards Navy during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. Shamkhani served as defense minister under reformist President Mohammad Khatami between 1997 and 2005. As defense minister, he played a leading role in improving relations between Iran and Persian Gulf sheikhdoms. In 2004, Shamkhani received Saudi Arabia’s highest medal, the Order of Abdulaziz al Saud, from King Fahd for his efforts. Shamkhani directed the Iranian Armed Forces’ Center for Strategic Studies from 2005 until his appointment by Rouhani.

The following is a rare interview that Shamkhani gave while defense minister. It originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times on November 15, 1998.

Ali Shamkhani

Iran's Top Defense Official Probes Depth of Detente With U.S.

By Robin Wright

November 15, 1998

TEHRAN — Ali Shamkhani might not be Iran's top military official today if only he had liked Los Angeles a bit more in the mid-1970s. After high school, Shamkhani went to Los Angeles with his father and two brothers. His brothers stayed, one to study medicine, the other mechanical engineering, but not Shamkhani. "I didn't approve of the culture," he explained during a recent conversation in his large office in Tehran's Defense Ministry Building No. 2.

So, he went home to study engineering at Ahwaz University in the city where he was born--and charted a far different course. While at college, Shamkhani launched an underground movement to challenge Iran's monarchy. After the 1979 revolution, when he was still in his 20s, Shamkhani was rewarded with a job as deputy commander of the new Revolutionary Guards. During Iran's 1980-88 war with Iraq, one of the century's grisliest conflicts, he led key ground offensives. Afterward, he was named commander of Iran's navy, reaching the rank of rear admiral before he hit 40. Last year, after a stunning presidential election upset by reformer Mohammad Khatami, Shamkhani was tapped to be defense minister. Today, Shamkhani, 43, heads a force of more than 500,000, the largest military in the Middle East.

Marine Corps Gen. Anthony Zinni, head of the U.S. Central Command, said Khatami's victory had produced "a more polite and professional attitude" among Iran's naval forces in the Persian Gulf. In contrast, he said, a year earlier he "went to bed worrying that we would have a confrontation at sea" because of a "very hostile" Iranian navy. But Zinni also charged that Iran's naval buildup of antiship missiles and mine-laying submarines, plus a nuclear-weapons program that could be "on track within five years," will make Iran "a more significant problem than Iraq. . . . In the longer term, Iran is a greater threat." He also charged that the Islamic republic still has not abandoned efforts to build weapons of mass destruction or support extremist groups.

In a CNN interview in January, Khatami proposed people-to-people exchanges with Americans to tear down "the wall of mistrust." Since then, both Tehran and Washington have launched the most serious efforts in two decades of hostilities to repair relations. But Zinni's warning underscores the fact that the biggest gap between the two countries remains in the defense arena.

Iran is particularly angered that the U.S. Congress responded to Khatami's diplomatic overture with Radio Free Iran, launched this month and mandated to challenge the government. Tehran also labels Washington as hypocritical for selling billions in new arms to Iran's neighbors, despite Tehran's recent detente with Gulf Arabs, while criticizing Iran's efforts to rearm after its massive losses in the war with Iraq.

Iran's fears stem from its eight-year war with Iraq. Despite its far larger population, Iran was forced to accept a U.N. cease-fire in 1988 after massive human and material losses. Iraq had been greatly helped in the conflict by its use of chemical weapons and access to U.S. satellite intelligence.

In his limited spare time, Shamkhani, the only Arab in Iran's cabinet, likes to mountain climb at least three mornings a week, aides say. He gets up at 4 a.m. so that he can still arrive at the office by 7 a.m. Married to a teacher, he is the father of four children.

Question: Gen. Anthony Zinni, the U.S. commander in the Persian Gulf, said recently that Iran will be a more significant long-term problem in the Gulf than Iraq. What is your reaction to this?

The American military has a special view, and it's based on creating a hypothetical enemy and basing their policies on this hypothetical enemy. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union was this enemy. After the Cold War, [Harvard professor Samuel] Huntington made up this theory about a clash of civilizations based on the suggestions or ideas from the Pentagon. We think this hypothesis does not apply to the current trends. Policies based on theories like Huntington's are from the 1940s. They're old-fashioned.

Iranian Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi gave a speech in New York in September suggesting there might be ways, directly or indirectly, for Iran and the U.S. to cooperate in three areas: narcotics control, terrorism and weapons of mass destruction. Can this happen?

Can you insult someone and at the same time claim to be his friend? Is it possible to point a pistol at someone and claim to be his friend? Is it logical to hold joint maneuvers if the enemy is someone whom you supposedly want to make friends with? This is exactly what the U.S. is doing.

It's insulting Iran through Radio Free Iran. The U.S. has a great presence in the Persian Gulf. In no period of its history has the Gulf seen such a large foreign [naval] presence. You're also holding joint maneuvers with Israel and Turkey near our borders, and the Israelis are threatening us in different ways. You think that some countries are providing Iran technical assistance, and you're exerting pressure on these countries. So, actually, you're not for the solution of long-standing problems between Iran and the U.S. You have just altered your dialect. But what you're doing is the same as before.

The U.S. is concerned about Iran's expanding missile program in cooperation with other governments. Why does Iran feel a need to expand its missile capability? What are Iran's goals?

Why do the Israelis buy F-15s with a range of 4,000 kilometers? Why do the Israelis enjoy nuclear weapons? Why shouldn't we have [medium-range] Shahab-3 missiles? We are quite a large country. Your question generates some other questions for us. Why do you ask? It is our natural right.

Our defensive strategy is one of deterrence. We have never started a war against anyone. And we wouldn't do so in the future. But it is also our natural right to prevent anyone from encroaching on our security. We have sustained great losses from our war with Iraq, and we could not neglect this experience.

Many Western governments are convinced, based on a pattern of acquisitions, that Iran is attempting to build a nuclear-weapons program.

It was just two years ago that U.S. military experts claimed that Iran was going to buy $7 billion in military equipment. And they made different campaigns concerning this. At the end of the year, they announced that Iran hadn't done so. They attributed this failure to economic problems.

Don't you think it's unfair to make a lie and then make use of it as the basis for other lies? First of all, we didn't intend to make such large purchases, and on the other hand, our failure to make such purchases was not due to economic problems. The same case applies to Iran's nuclear drive and the campaign the U.S. is conducting.

The Americans always make four allegations against us. One of them is about weapons of mass destruction, in other words, nuclear weapons. But Iran is one of the signatories of the Nonproliferation Treaty. We have not prevented any kind of [International Atomic Energy Agency] inspections. Our activities are for peaceful means. I have no information about the activities in that field, and I'm not interested.

Do the recent nuclear tests by Iran's neighbors Pakistan and India produce greater concern or interest in nuclear weapons?

We won't breach our undertakings with the Nonproliferation Treaty or the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Of course, we're concerned. But it doesn't make any alterations in our plans. We won't make use of this natural right to build a nuclear weapon.

What are the major threats to Iran and how has recent diplomacy by Iran changed the perceptions of the threats?

We feel threatened by two things: One is the foreign military presence in the Persian Gulf, especially the U.S. military presence. And second is the ethnic movements in Central Asia. We expect the American nation to alleviate one of these challenges by drawing back or evacuating from the Persian Gulf.

But the U.S. presence indirectly helps protect Iran from further Iraqi aggression.

A powerful Iraq was made partly by the U.S. What guarantees can you give us not to create another Iraq? Have you ever stood in the rain? Have you opened the umbrella? The stick holds the umbrella. The U.S. was the stick for Iraq [during the Iran-Iraq War].

I had two brothers martyred by Iraq in the war. Do you think we hold the American regret now as enough? We feel they are acting against our interests in the Gulf.

U.N. and U.S. officials say Iran has twice cut off Iraq's sanctions-busting oil shipments smuggled inside Iranian waters. But both times, Iran then allowed Iraq to resume shipments. Why?

You expect too much. We have offered more than 2,500 martyrs to stop narcotics [from Afghanistan], to prevent transit to the West and the U.S. What have you done in return? In fact, we have offered these martyrs to protect you. Let me tell you, you have made our borders insecure. And if we just build up our forces to face this challenge [from Afghanistan], you make a campaign about Iran's military power.

Naturally, we can't fight on several fronts. Our capabilities are limited. Our ability to control the developments in the Persian Gulf depends on the distribution of our forces.

We are always on a continuous basis controlling in accordance with the U.N. resolutions on Iraqi oil exports. If there has been some kind of smuggling of Iraqi oil, it has been because of some kind of faults resulting from problems and difficulties within the Iranian military because we can't centralize our forces. Ask the U.S. forces: Can they fight on three fronts?

Last year, President Khatami said that while Iran did not agree with the peace process between Israel and the Palestinians, Iran would not sabotage it. The latest phase of the accord has been sharply criticized by Iran. Will Iran do anything to undermine the Wye accord?

We just reiterate what President Khatami has said.

Following the murder of Iranian diplomats in Afghanistan, Iran deployed 200,000 troops on the border and conducted military exercises. What are the chances Iran will go to war? And given the Soviet experience in Afghanistan, is this a war Iran thinks it can win?

It's quite a mistake to compare the Iranian position on Afghanistan to the presence of Soviet forces in Afghanistan. The Russians committed the same mistake as the British [colonial army] in 1818. What we are really after is to solve our problems through means other than confrontation. What we hope to achieve is the punishment of the assassins of our diplomats, the freeing of our prisoners, the prevention of genocide in Afghanistan and the prevention of narcotics trafficking.

We have quite a good record during our eight years of defense against Iraq, including irregular warfare. And we think our forces can't be compared with the Soviet forces. But we hope it will not come to war. It's up to the Taliban [who rule Afghanistan] to alleviate our concerns and avoid confrontation. We also think that international organizations can play a great role.

Robin Wright has traveled to Iran dozens of times since 1973. She has covered several elections, including the 2009 presidential vote. She is the author of several books on Iran, including “The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and transformation in Iran” and “The Iran Primer: Power, Politics and US Policy.” She is a joint scholar at USIP and the Woodrow Wilson Center. See her chapter, “The Challenge of Iran” from "The Iran Primer."

Born in 1955, Shamkhani is an Arab from Ahvaz near the Iraqi border. He commanded the Revolutionary Guards Navy during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. Shamkhani served as defense minister under reformist President Mohammad Khatami between 1997 and 2005. As defense minister, he played a leading role in improving relations between Iran and Persian Gulf sheikhdoms. In 2004, Shamkhani received Saudi Arabia’s highest medal, the Order of Abdulaziz al Saud, from King Fahd for his efforts. Shamkhani directed the Iranian Armed Forces’ Center for Strategic Studies from 2005 until his appointment by Rouhani.

Born in 1955, Shamkhani is an Arab from Ahvaz near the Iraqi border. He commanded the Revolutionary Guards Navy during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. Shamkhani served as defense minister under reformist President Mohammad Khatami between 1997 and 2005. As defense minister, he played a leading role in improving relations between Iran and Persian Gulf sheikhdoms. In 2004, Shamkhani received Saudi Arabia’s highest medal, the Order of Abdulaziz al Saud, from King Fahd for his efforts. Shamkhani directed the Iranian Armed Forces’ Center for Strategic Studies from 2005 until his appointment by Rouhani. Iran is particularly angered that the U.S. Congress responded to Khatami's diplomatic overture with Radio Free Iran, launched this month and mandated to challenge the government. Tehran also labels Washington as hypocritical for selling billions in new arms to Iran's neighbors, despite Tehran's recent detente with Gulf Arabs, while criticizing Iran's efforts to rearm after its massive losses in the war with Iraq.

Iran is particularly angered that the U.S. Congress responded to Khatami's diplomatic overture with Radio Free Iran, launched this month and mandated to challenge the government. Tehran also labels Washington as hypocritical for selling billions in new arms to Iran's neighbors, despite Tehran's recent detente with Gulf Arabs, while criticizing Iran's efforts to rearm after its massive losses in the war with Iraq.