On December 8, President Hassan Rouhani presented a $43 billion budget to parliament for the upcoming fiscal year, which starts in March 2020. What challenges does Rouhani face?

This year’s budget is the first since the U.S. “maximum pressure” campaign kicked into high gear in May 2019. The cancellation of sanctions waivers that month drove oil exports – Iran’s most important source of revenue – down to less than 500,000 barrels per day, an 80 percent drop from a year prior. Rouhani’s challenge was to design a budget with significantly lower oil revenues while preserving the social spending that Iranians expect and the defense spending that the military demands. “This is a budget to resist sanctions ... with the least possible dependence on oil,” Rouhani told lawmakers. “This budget announces to the world that despite sanctions we can manage the country.”

For the government, striking a balance is critical to ensuring political and economic stability. The protests in November 2019 demonstrated the stakes. An estimated 200,000 protesters took to the streets in more than 100 cities and towns. Security forces killed at least 300 people; the protests were the deadliest since the 1979 revolution. They were sparked by the abrupt increase in the price of gasoline and the introduction of a fuel rationing system, steps designed to improve the government’s balance sheet before finalizing the budget.

Parliament is required to mark up the bill and suggest changes. But lawmakers are essentially being presented with a fait accompli. In an unusual move, the budget had already been reviewed by the Supreme Council for Economic Coordination, which includes the heads of the three branches of government; it reports to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Given the council’s intervention, the parliament had limited room for maneuver.

What are the broad outlines of the budget and how does it compare to the previous year’s budget? How is it likely to impact the average Iranian?

The budget calls for government spending of 5,638 trillion rials, or $43 billion at the current free-market exchange rate. In rial terms, this is an eight percent increase over the previous budget. After accounting for high inflation, however, spending is actually shrinking by about 17 percent. The World Bank estimates inflation will be 29 percent next year; the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts it will be 31 percent. The IMF also predicts that the economy will contract by 9.5 percent in 2019.

Given scarce resources, the government is trying to cushion the blow on the lower and middle classes. Public salaries will increase by 16 percent, while welfare and development spending will remain roughly the same. In line with the fuel subsidy reduction in November, the government cut subsidy spending by 74 percent. But the plan to increase cash transfers may move two million lower-income Iranians out of poverty, according to an Iranian-American economist. The Rouhani administration has also pledged that it will continue to allocate $14 billion for the import of basic goods and medicine at low prices.

What does the budget assume about revenue and the overall economy next year?

The Rouhani government made several assumptions that could prove overly optimistic. Mohammad-Baqer Nobakht, the chief of the government’s budget office, said the government expects overall economic growth of two percent in 2020-21. This is significantly higher than the estimates of international observers. The World Bank and the IMF estimate growth to be 0.1 percent or lower.

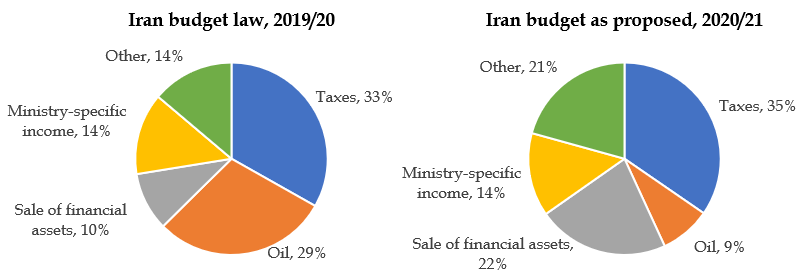

The estimate for oil revenue appears even more farfetched. Last year, oil sales made up 29 percent of government revenues. For 2020, the government is counting on oil to provide only nine percent of revenues. The budget assumes that Iran will export one million barrels per day at $50 per barrel—for a total annual income of just over $18 billion. The estimated price is conservative, but the volume of sales may be optimistic, given U.S. sanctions. As of December 2019, Iran exported about 400,000 barrels per day with global oil prices at $63 per barrel, although Iran was forced to sell crude at a steep discount to incentivize buyers. Iran’s precise monthly revenue from oil sales was difficult to determine because its sales arrangements were secret. In addition to offering oil at a cheaper price, Iran in the past has used oil exports to pay off debt or for barter, meaning it was not receiving revenue from the sales. Without major U.S. sanctions relief, Iran has no clear path to reach one million barrels. Even if Iran sold oil at $65 per barrel in 2020, it would still need to export about 770,000 barrels per day to achieve the anticipated $18 billion in revenue.

The budget’s assumptions about tax revenue also appear too sanguine. The government plans to hike annual tax revenue by 13 percent to 1,950 trillion rials or $15 billion, but authorities may have trouble collecting anywhere close to that much. The government started to crack down on tax evasion, but it has been wary about increasing tax rates on individuals or businesses already under severe pressure. Moreover, the budget continues to grant tax exemptions to foundations and religious organizations affiliated with the supreme leader. The national tax authority reported in October that about half of the highest-earning people and organizations are exempt from taxes. In November, Rouhani acknowledged that 1,500 trillion rials in tax revenues is more realistic.

What portion of the budget would go towards national security?

It’s difficult to put an overall price tag on defense spending, as funding is divided across scores of line items throughout the budget. Parts of the armed forces also receive significant amounts of off-the-book funding from business enterprises and smuggling. But the explicit line items for the major military bodies do suggest a trend.

The Army, Revolutionary Guards, and Ministry of Intelligence all received budget increases of about 20 percent. The Ministry of Defense, which plays an important role in military acquisition, received an 8.5 percent increase, while the domestic law enforcement forces received an increase of 14 percent. All of these increases are below the estimated rate of inflation, meaning that their funding in real terms is declining. The Basij paramilitary received the most dramatic cut of all; its funding was cut almost in half.

But entities associated with the Revolutionary Guards may benefit from other provisions in the budget. The government is planning to double the amount of revenue it earns from selling state companies. In theory, privatization should benefit the private sector and improve inefficient government-run enterprises. But given Iran’s weak private sector, the buyers of privatized state assets tend to be semi-state entities, many of which are linked to hardline power centers, including the Revolutionary Guards. If the government goes through with these sales, hardline elements stand to gain handsomely.

Will Iran receive any outside financial help?

It’s unlikely. When he presented the budget, Rouhani announced that Russia will provide a $5 billion loan to support infrastructure projects next year. Russia has yet to confirm this initiative, and Moscow was hesitant to support Iran economically in 2019, partly to avoid running afoul of U.S. sanctions. If it goes through, the $5 billion loan would support two projects: the construction of a power plant and a train line. The Russian loan would not fund the government’s operating budget, although it could potentially allow the government to reprogram funds earmarked for development projects –roughly 12 percent of the budget–for other purposes.

Europe has vowed to take small steps to support humanitarian or non-sanctioned trade with Iran. INSTEX, the European financial mechanism designed to bypass U.S. sanctions, was slated to process its first transactions in December 2019, although the timing has repeatedly been delayed. INSTEX is unlikely to handle large quantities of trade with Iran, meaning it will not significantly ease pressure on the government to continue allocating dollars for humanitarian imports. Switzerland is implementing a separate channel for food and medicine that may help ease immediate shortages. But, similar to INSTEX, it is unlikely to have a major budgetary impact.

Could the budget proposal—and its implications—trigger more protests?

The flashpoints of protests are difficult to predict, but Iran will face a difficult year even if, as the World Bank and IMF expect, the economy starts to stabilize. Access to critical foreign reserves has dwindled. The rial, which remained relatively stable for the last six months of 2019, has started to lose ground against the dollar. The government will likely have to impose more austerity measures as the year goes on to adjust for the budget’s optimistic assumptions about growth, oil revenue and tax collection.

But even renewed bouts of protest may not signify the death throes of the Islamic Republic. The November demonstrations showed that the security forces remain loyal, efficient, and brutal. And the government can still lean on vast amounts of off-the-books resources stashed away in religious institutions and military-linked entities to keep the lights on.

*Updated April 2, 2020

The government approved a revised budget on March 19, 2020, following amendments by the parliament and Guardian Council. How was the approval process different from previous years and what were the major changes?

Parliament rejected Rouhani’s budget bill on February 24 by a vote of 67 in favor and 114 against (with many lawmakers absent). Some criticized the plan as unrealistic while others were concerned that the spread of coronavirus made further parliamentary review too dangerous. In response, parliament speaker Ali Larijani requested Supreme Leader Khamenei’s intervention. On March 3, the supreme leader issued a state decree permitting the budget to be implemented without a parliamentary vote. The parliament’s combined budget committee made further changes in consultation with the Guardian Council; another body, the Council for the Discernment of Expediency, was also involved, to litigate differences between the parliament and Guardian Council. The budget was finalized on March 19. The supreme leader’s formal intervention was highly unusual and underscored the parliament’s eroding role in the Islamic Republic as well as the extraordinary economic and public health conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The revised budget increases spending by 15 percent to 6,498 trillion rials compared with the budget submitted by Rouhani. This includes an increase in civil servant salaries as well as a 25 percent increase in spending on development projects. In addition, the revised budget hikes spending on defense and law enforcement entities. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ budget increased by one-third over the level proposed by Rouhani to 243 trillion rials; this is a more than 60 percent increase in the amount it received last year, well above the rate of inflation. Funding for the Basij militia increased as well, to 22 trillion rials—more than double what Rouhani proposed and about a one-third increase over last year. The domestic Law Enforcement Forces received 10 percent more than what Rouhani had proposed, as did the regular Army. The defense allocations signal that despite the coronavirus crisis, the government intends to maintain its repressive capacity at home and its military capabilities abroad.

Rouhani subsequently announced that the government would spend 1,000 trillion rials to support individuals and companies facing coronavirus-related pressure; this is equivalent to $6.3 billion at the current market rate or 15 percent of planned expenditures this year. The source of the stimulus was unclear, but Rouhani is unlikely to enforce across-the-board budget cuts to free up money. Rouhani had already asked for $1 billion from the National Development Fund to spend on medical supplies, and he may ask for more as the pandemic’s economic impacts become clearer. Iran has also requested access to $5 billion from the International Monetary Fund, although the United States may try to block this disbursement.

Henry Rome is an Iran analyst at Eurasia Group.