President Trump’s announcement on May 8 — to withdraw from the 2015 nuclear deal and reimpose sanctions — began to isolate Iran again. “We’re going to deny them the benefit of the economic wealth that has been created and put real pressure, so that they’ll stop the full scale of the sponsorship of terrorism with which they’ve been engaged in these past years,” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said on May 13. Any foreign companies doing business with the United States could face serious penalties if they continued doing business with Iran. On June 26, President Hassan Rouhani accused the United Sates of waging a “psychological, economic and political war” against Iran.

Khamenei Orders Crackdown After Tehran's Biggest Protests in Years https://t.co/9d84ExHJJS pic.twitter.com/NxpgCmNyTR

— The Voice of America (@VOANews) June 27, 2018

Iran’s economy was already facing several challenges before Trump’s decision. In the 2015 deal, Tehran agreed to curb its nuclear program in exchange for lifting of international sanctions. Iran’s economy improved modestly after the deal was implemented in January 2016. But growth was largely limited to the oil and gas sector. Iran did not receive the anticipated foreign investment. In a January 2018 poll, nearly 70 percent of Iranians said the economy was bad. The World Bank projected the real GDP growth rate would drop to 4.3 percent for fiscal year 2017-2018, down from 12.5 percent from the previous year.

In December 2017 and January 2018, tens of thousands took to the streets to protest rising prices, unemployment, the gap between rich and poor, and corruption. Unemployment hovered around 12 percent in early 2018, with unofficial estimates higher, especially for women and youth. In April, Iran’s currency, the rial, declined rapidly, triggering public panic and a race on foreign currency. In June 2018, protests broke out in Tehran over rising prices. In an open letter, 187 out of 290 lawmakers urged President Hassan Rouhani to change up his economic team to deal with the rial’s devaluation.

Source: Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland and IranPoll.com

Related article: Iran's Troubled Economy, By the Numbers

After Trump’s withdrawal in 2018, the other five parties to the accord – Britain, China, France, Germany, and Russia – explored ways to keep the deal alive. Iran stipulated that economic benefits had to be guaranteed, or it would consider restarting its nuclear program on an industrial scale. Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif visited Beijing, Moscow and Brussels to negotiate a way forward.

European Response

The European Union scrambled on ways to shield companies from U.S. penalties. “Our governments remain committed to ensuring the agreement is upheld, and will work with all the remaining parties to the deal to ensure this remains the case including through ensuring the continuing economic benefits to the Iranian people that are linked to the agreement,” the foreign ministers of Britain, France, and Germany said in a joint statement on May 8. Among the options was updating and activating the Blocking Statute, an E.U. law that forbids citizens from “complying with U.S. extraterritorial sanctions, allows companies to recover damages arising from such sanctions from the person causing them, and nullifies the effect in the E.U. of any foreign court judgements based on them.” The Blocking Statute will enter into force in August if no objections are raised by the European Parliament or Council. The potential impact is unclear because the original law was never used.

On May 16, European Council President Donald Tusk criticized U.S. policies in a tweet:

Looking at latest decisions of @realDonaldTrump someone could even think: with friends like that who needs enemies. But frankly, EU should be grateful. Thanks to him we got rid of all illusions. We realise that if you need a helping hand, you will find one at the end of your arm.

— Donald Tusk (@eucopresident) May 16, 2018

On June 4, the foreign and finance ministers of Britain, France and Germany, as well as the E.U. foreign policy chief, formally requested exemptions from U.S. sanctions for European companies. “In their current state, U.S. secondary sanctions could prevent the European Union from continuing meaningful sanctions relief to Iran,” they wrote in a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. “As allies, we expect that the United States will refrain from taking action to harm Europe’s security interests.”

On June 6, the European Investment Bank (EIB) rejected an E.U. executive plan to do business with Iran to salvage the JCPOA. “A prerequisite for its business model is that the bank should remain a solid and credible institution on the international capital markets, and this would be incompatible with ignoring possible sanctions against Iran,” a bank spokesman told Reuters. “The E.U. bank is not the right tool.” European Commissioners had agreed to enable the bank to work in Iran, where it had never done business. In July, E.U. lawmakers voted to grant the EIB the ability to invest in Iran but did not obligate it to do so. EIB President Werner Hoyer said the not-for-profit lender could not play an active role in the Islamic Republic. The bank’s refusal accentuated the limited options available to the European Union to maintain trade with Iran.

On June 6, the European Investment Bank (EIB) rejected an E.U. executive plan to do business with Iran to salvage the JCPOA. “A prerequisite for its business model is that the bank should remain a solid and credible institution on the international capital markets, and this would be incompatible with ignoring possible sanctions against Iran,” a bank spokesman told Reuters. “The E.U. bank is not the right tool.” European Commissioners had agreed to enable the bank to work in Iran, where it had never done business. In July, E.U. lawmakers voted to grant the EIB the ability to invest in Iran but did not obligate it to do so. EIB President Werner Hoyer said the not-for-profit lender could not play an active role in the Islamic Republic. The bank’s refusal accentuated the limited options available to the European Union to maintain trade with Iran.

Individual businesses ultimately will make their own calculations even if the European Union finds ways to shield companies. The final decision may depend on balancing whether the risk of running afoul of U.S. sanctions outweighs the potential benefits of doing business with Iran. In 2015, the French bank BNP Paribas was ordered to pay $9 billion in penalties for violating U.S. sanctions against Iran, Cuba and Sudan. “No reasonable company wants to be made the test case of this, even if their government wants to stand up,” Elizabeth Rosenberg, a former senior advisor at the U.S. Treasury, said in April. By July, more than 50 international firms had announced that they were leaving the Iranian market, according to the State Department.

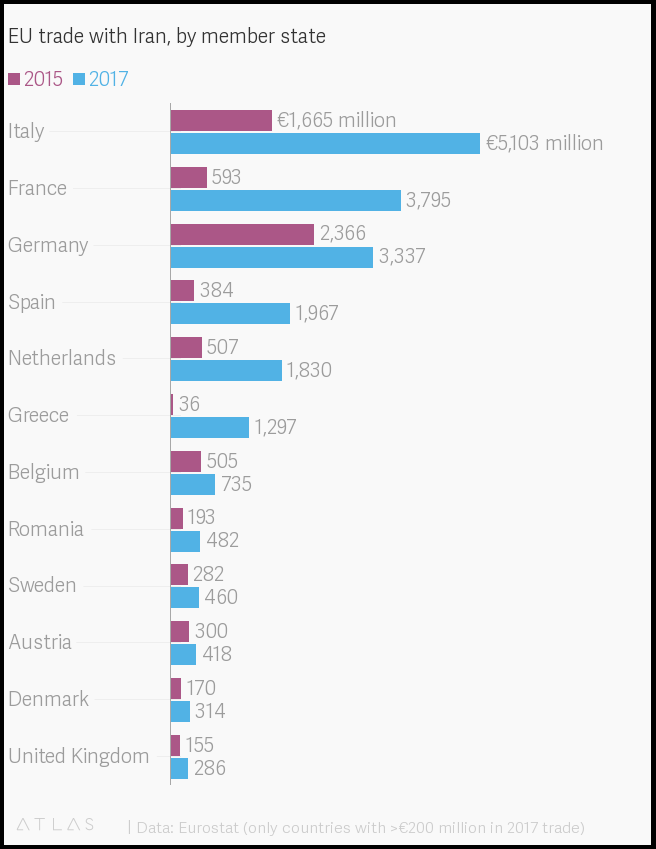

The potential benefits to Europe of maintaining trade with Iran are relatively slim. E.U. trade with Iran jumped from $9.1 billion in 2015 to nearly $25 billion in 2017 as a result of the nuclear deal. Yet trade with Iran accounted for less than one percent of E.U. trade in 2017. Iran was European Union’s 33rd largest trade partner — behind Kazakhstan and Serbia. Europe, conversely, is far more important for Iran. In 2017, it was Iran’s third largest trading partner after China and the United Arab Emirates.

France

France’s response initially was the most assertive. Europe should not accept the United States as the “world’s economic policeman,” Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said. Another official called it “an important test of sovereignty.” France was Europe’s second largest trade partner with Iran in 2017. Bilateral trade soared in 2017 to $4.2 billion, up nearly 80 percent compared with 2016. Iran exported $2.6 billion worth of goods to France, mostly oil. France exported $1.6 billion in goods to Iran. But several major French firms have started winding down their Iran business. The United States rejected a French request for sanctions exemptions, Finance Minister Le Maire said in an interview published on July 13.

France’s response initially was the most assertive. Europe should not accept the United States as the “world’s economic policeman,” Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said. Another official called it “an important test of sovereignty.” France was Europe’s second largest trade partner with Iran in 2017. Bilateral trade soared in 2017 to $4.2 billion, up nearly 80 percent compared with 2016. Iran exported $2.6 billion worth of goods to France, mostly oil. France exported $1.6 billion in goods to Iran. But several major French firms have started winding down their Iran business. The United States rejected a French request for sanctions exemptions, Finance Minister Le Maire said in an interview published on July 13.

- In May, energy giant Total announced that it will pull out of a $2 billion project for developing the South Pars gas field, the world’s largest. Total “cannot afford to be exposed to any secondary sanction, which might include the loss of financing in dollars by U.S. banks for its worldwide operations,” it said.

- In June, Airbus said it probably would not be able to deliver the remaining 97 aircraft that Iran ordered, worth up to $20 billion. Iran had only received three aircraft from Airbus, an international conglomerate based in France.

- In June, aircraft manufacturer ATR said it would stop delivering planes to Iran. IranAir had committed to buy 20 planes from ATR, eight of which had been delivered. ATR was seeking a U.S. waiver to deliver completed aircraft and those that were already in production. On August 5, however, ATR delivered five more planes less than two days before U.S. sanctions were due to be reimposed.

- In June, PSA Group, the maker of Peugeot and Citroen automobiles, began winding down its business in Iran even as it sought a U.S. waiver with French government support. Iran was the company’s biggest market outside of France.

- In June, carmaker Renault said it would not abandon the Iranian market, even if it means downsizing. “When the market reopens, the fact of having stayed will certainly give us an advantage,” said CEO Carlos Ghosn. But he also said the company would be careful to comply with U.S sanctions. In July, COO Thierry Ballore said Renault’s Iran operations would likely be put on hold.

- In July, Scor SE, a property and casualty and life reinsurer, said it was pulling out of Iran.

- In July, CMA CGM, operator of the world’s third largest container shipping fleet, said it was pulling out of Iran.

Germany

Germany has historically been one of Iran’s top European trading partners, even before the 1979 revolution. After the JCPOA, trade between Germany and Iran flourished. As of mid-2018, some 120 German companies had staff in Iran, and some 10,000 German firms had business with Iran, according to Reuters. Trade rose to $3.9 billion in 2017 from $2.7 billion in 2015. Imports from Iran grew by nearly a quarter to $383 million. German exports include high-end products, such as chemical and electrical goods, construction equipment, and industrial machines. The U.S. ambassador in Berlin, Richard Grenell, tweeted a warning to German companies after Trump’s announcement.

Germany has historically been one of Iran’s top European trading partners, even before the 1979 revolution. After the JCPOA, trade between Germany and Iran flourished. As of mid-2018, some 120 German companies had staff in Iran, and some 10,000 German firms had business with Iran, according to Reuters. Trade rose to $3.9 billion in 2017 from $2.7 billion in 2015. Imports from Iran grew by nearly a quarter to $383 million. German exports include high-end products, such as chemical and electrical goods, construction equipment, and industrial machines. The U.S. ambassador in Berlin, Richard Grenell, tweeted a warning to German companies after Trump’s announcement.

As @realDonaldTrump said, US sanctions will target critical sectors of Iran’s economy. German companies doing business in Iran should wind down operations immediately.

— Richard Grenell (@RichardGrenell) May 8, 2018

A handful of companies have indicated that they will cut business ties with Iran.

- In May, Siemens AG, which is involved in healthcare, energy and other industries, said it could no longer do business in Iran.

- In May, Wintershall AG, an energy firm, told its Iranian partners it may not secure funding for oil projects because its parent company does business in the United States.

- In May, Volkswagen said it was monitoring the situation closely. It “complies with all applicable national and international laws and export regulations,” a spokesperson said. Volkswagen began exporting cars to Iran in 2017 for the first time in 17 years.

- In May, insurer Allianz said it was winding down business with Iran.

- In August, Daimler, the maker of Mercedes-Benz cars, said it had suspended its activities. In 2016, it announced plans to return to Iran, but it had not yet resumed production or sales there.

The United Kingdom

![]() U.K.-Iran trade more than doubled between 2015 and 2017 under the nuclear deal. In 2017, Britain exported nearly $300 million in goods to Iran. Iran exported some $64 million in goods to Britain.

U.K.-Iran trade more than doubled between 2015 and 2017 under the nuclear deal. In 2017, Britain exported nearly $300 million in goods to Iran. Iran exported some $64 million in goods to Britain.

- In May, Serica Energy initially said it was “evaluating the implications” of renewed U.S. sanctions. But, a few weeks later, it reaffirmed its commitment to buying BP’s stake in a North Sea gas field. The other half is owned by the National Iranian Oil Company.

Italy

Italian companies were heavily invested in the Iranian market before the 1979 revolution. Energy and construction companies remained until international sanctions were imposed in 2011 and 2012. Italy was Europe’s top trading partner with Iran in 2017. Bilateral trade amounted to nearly $6 billion, up from $1.9 billion in 2015. In June 218, oil company Eni said its limited operations in Iran would not be affected by U.S. sanctions. In July, Denikon Company signed a memorandum of understanding to promote international investment in a solar energy project in Yazd province. But at least two other Italian companies said they were pulling out.

Italian companies were heavily invested in the Iranian market before the 1979 revolution. Energy and construction companies remained until international sanctions were imposed in 2011 and 2012. Italy was Europe’s top trading partner with Iran in 2017. Bilateral trade amounted to nearly $6 billion, up from $1.9 billion in 2015. In June 218, oil company Eni said its limited operations in Iran would not be affected by U.S. sanctions. In July, Denikon Company signed a memorandum of understanding to promote international investment in a solar energy project in Yazd province. But at least two other Italian companies said they were pulling out.

- In May, Italian steel manufacturer Danieli announced that it stopped seeking financial coverage for Iranian orders worth $1.8 billion.

- In June, Saras was examining how to wind down its Iranian oil purchases ahead of the deadline because it “cannot defy the United States.”

- In June, Gruppo Ventura said it was no longer expecting to build railroad tracks in Iran. The company had signed a $2.3 million contract in 2017 and had already started work.

Other European Countries

Several other European firms have also taken steps to protect themselves. Companies with stakes in Iran’s energy industry were the most cautious.

- In May, Torm, a Danish oil tanker operator, said it stopped taking news orders in Iran.

- In May, Maersk Tankers, a Danish company, announced it would “perform customer agreements entered into before May 8 and ensure that they are wound down by November 4.”

- In May, Switzerland-based MSC, the world’s second largest container shipping group, informed its clients that it was “ceasing to provide access to services to and from Iran.” It stopped taking new bookings.

- In May, Swiss Banque de Commerce et de Placements suspended new transactions with Iran.

- In June, Austrian energy group OMV said it would finish seismic studies in Iran before pulling out. “U.S. sanctions are a much bigger risk for OMV’s business than any possible compensation that Europe ... could offer,” Chief Executive Rainer Seele told Reuters.

- In June, Austria’s Oberbank, one of the first European banks that financed new ventures in Iran, announced that it will halt its business in the Islamic Republic.

- In June, Belgian financial group KBC said it would only conduct transactions with Iran involving humanitarian goods as defined by the U.S. Treasury.

- In August, Danish engineering company Haldor Topsoe, said it would cut 200 jobs, about seven percent of its workforce, due to reimposed U.S. sanctions on Iran.

- In August, Swiss railway company Stadler Rail put plans to deliver subway cars for use in Tehran on hold. The deal was reportedly worth $1.4 billion.

Back in Vienna together with President Rouhani, celebrating 160 years of diplomatic relations. Fruitful discussions with Austrian hosts - holding EU presidency - as well as business community. Commitment to JCPOA vividly on display. Imperative to translate will into action. pic.twitter.com/8BFR91aa1w

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) July 4, 2018

China

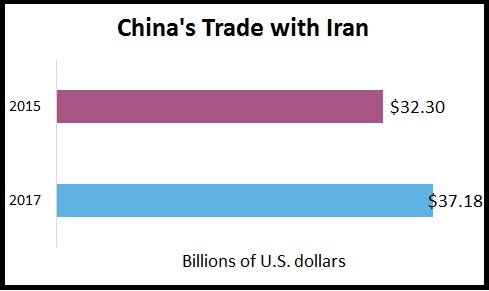

Chinese and Russian companies could capitalize as European companies withdraw. After Trump’s announcement, Zarif’s first two stops on his international trip were Beijing and Moscow. China is Iran’s top trading partner. In 2017, trade exceeded $37 billion—a 15 percent increase from 2015. Beijing “has always been a friend” during “rainy days,” Zarif said in Beijing on May 13. In April, China purchased 671,000 barrels of Iranian oil per day. In June, China’s Commerce Ministry said its firms would continue to trade with Iran despite the threat of U.S. sanctions. The statement came amid rising tensions between Washington and Beijing over trade.

Good and substantive meetings with counterparts in Beijing & Moscow; heading to meet with EU High Rep and E3 FMs in Brussels. Will soon determine how P4+1 can guarantee Iran’s benefits under the #JCPOA, and preserve this unique achievement of diplomacy. pic.twitter.com/qH51vd7Dby

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) May 14, 2018

President Xi Jinping criticized China’s opposition to the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal. “With their unilateral spirit and disregard of commitments and regulations, Americans are seeking to change the international order for their own benefit,” he said after meeting President Hassan Rouhani in June in Shanghai. “We are determined to cement economic relations with Iran.”

The Chinese state-owned oil company CNPC is ready to take Total’s stake in a huge South Pars gas project, Iran’s oil minister, Bijan Namdar Zanganeh, said on May 17. The South Pars field has the world’s largest natural gas reserves. Russian and Chinese dominance in the Iranian market would not benefit the United States or Europe, Total’s CEO, Patrick Pouyanné, warned on May 17. “It’s a huge opportunity for China and Russia to cement relationships with Iran,” Philip K. Verleger, an energy economist who worked in Republican and Democratic administrations, told The New York Times.

In May, Sinopec, another large Chinese-state oil company, sent representatives to Tehran to negotiate a $3 billion deal to develop the Yadvaran oil field. Royal Dutch Shell PLC was originally interested in the project but reportedly concluded in March that the sanctions risk was too great. The deal could be one of the biggest foreign investments in a decade, according to The Wall Street Journal. In July, Sino Steel Company signed a memorandum of understanding to construct a solar power plant and solar panel factory in Yazd province. The state-owned firm had reportedly invested $2.5 billion in Iran by July 2018.

Chinese and Russian companies that are not connected to the U.S. financial system could still buy Iranian crude oil despite sanctions, a former U.S. official said. They could also use alternative payment methods—such as using local currencies or cryptocurrencies—to buy Iranian oil. In early August, China reportedly refused to slash Iran oil imports but also agreed to not increase its purchases.

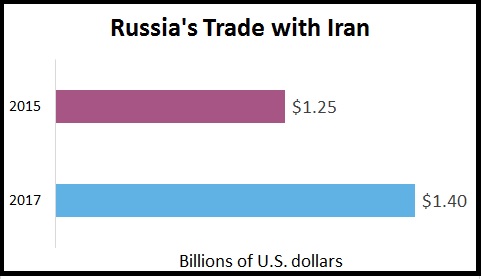

Russia

Russia claims it is committed to the nuclear deal and trade with Iran. “Moscow will continue to talk with other parties to support the JCPOA,” President Vladimir Putin assured Rouhani in June. “We are not scared of sanctions,” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov said during a visit to Tehran two days after Trump’s announcement. “Russian companies will continue doing business in Iran as if nothing happened at all” because they were already under U.S. sanctions, according to TeleTrade Chief Analyst Petr Pushkarev.

But Moscow and Tehran are actually competitors in the international energy market and do limited trade with each other. In the 2000s, bilateral trade peaked at $3 billion. In 2017, it was down to $1.7 billion. Renewed U.S. sanctions may hinder potential Russian investment in the oil and gas sector. In late 2017, Russia and Iran had signed agreements to collaborate on energy deals—involving Rosneft and Gazprom, both Russian companies—worth up to $30 billion. That deal may be endangered.

Russia could end up investing a “a lot less in Iran than it is capable of,” according to a Middle East Institute report in June. “Moscow considers Tehran a rival both geopolitically, with both trying to increase their influence in the Middle East, and in the energy market, as both are seeking out gas markets in Southwest and East Asia.” In May, Lukoil, Russia’s second biggest oil producer, said it was not moving forward with its Iranian projects. “For the moment, basically, we have everything on hold,” a company official said.

India

India is not a party to the JCPOA but it is an important player indirectly. After Saudi Arabia and Iraq, Iran has been India’s third largest source of oil since 2016. India, in turn, is a vital trading partner for Iran; it is the second largest importer of Iranian goods, largely from oil sales. India’s actions could have a significant impact on the Islamic Republic’s economy.

India had been keen to grow its economic ties with Iran. For years, it helped develop the Chabahar port in southeastern Iran to facilitate trade with Afghanistan and Central Asia – and bypass rival Pakistan. In 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed $500 million to the project. In February 2018, President Rouhani visited India and signed nine agreements, including a lease giving operational control of Chabahar to India for 18 months.

After Trump’s announcement, New Delhi vowed to sustain trade with Iran. “India follows only U.N. sanctions, and not unilateral sanctions by any country,” External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj said on May 28, hours before meeting Foreign Minister Zarif. India will seek exemptions from U.S. sanctions or at least try to minimize the reduction of its oil imports from Iran, a senior official told The Wall Street Journal. In June, India’s oil ministry reportedly told refiners to look for alternative oil sources.

Sushma Swaraj hold talks with her Iranian counterpart Javad Zarif, says India only recognises UN sanctionshttps://t.co/mfWXkCCPBe pic.twitter.com/3VYSnKUL0M

— Zee News (@ZeeNews) May 28, 2018

India continued to purchase Iranian oil since the deadline for cutting off business is not until November. Indian demand for Iranian oil rose significantly. In May, 2018, Indian imports from Iran surged to 705,000 barrels per day, the highest level since October 2016, when imports rose to 789,000 barrels per day. In June, the Indian state refiner Bharat Petroleum Corporation sought an extra one million barrels of oil for the month—more than double its usual monthly intake in the previous fiscal year—from the National Iranian Oil Company.

In 2012, India also refused to recognize U.S. sanctions. But it did eventually cut its Iranian oil imports by some 20 percent. In 2018, several Indian banks and companies have indicated that they will eventually curtail purchases or stop handling payments for Iranian oil to avoid being hit by U.S. sanctions.

- In June, the State Bank of India reportedly told Indian refiners that it would not handle oil payments to Iran as of November 4.

- In June, the Indian Oil Corp said that oil imports from Iran would be reduced in late August “unless a new payment route is established.”

- In May, Reliance Industries, which owns the world’s largest refining complex, planned to halt Iranian oil imports in October or November, Reuters reported.

- In June, Nayara Energy, one Iran’s biggest Indian customers, said it would find alternative oil sources to comply with U.S. sanctions. The company began cutting imports in June 2018 with plans to limit intake to three to four million barrels per month, down from six million barrels per month, Reuters reported. But the company said it had not planned any specific cut-backs.

- In May, two banks, IndusInd and UCO, told exporters to conclude all deals with Iran by August 6, according to the Federation of Indian Exporters Organization.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of "The Iran Primer" and "The Islamists" websites at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Photo credits: President Rouhani via President.ir; 5,000 rial note by Pol70117 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Click here for President Trump's announcement of the U.S. withdrawal.

Click here for the U.S. Treasury's statements on sanctions.

Click here for Iran's response.

Click here for world reactions.

Click here for congressional remarks.

Click here for Obama-era officials' reactions.

Click here for analysis by foreign policy and non-proliferation experts.

Click here for responses from around the Middle East.

Click here for Iranian media coverage.