John S. Park and Cameron Glenn

- Iran is a linchpin in China’s regional energy security strategy. Iran has a strategic commodity essential to China’s primary goal — sustainable economic development. The more China grows, the less it acts like a responsible stakeholder due to its energy needs.

- Iran has focused on rebuilding its refinery capabilities, hedging against U.S.-led sanctions, and advancing its nuclear energy capabilities. China plays an important role as a major commercial and political partner.

- An unintended consequence of U.S.-led sanctions is more opportunity for Iran and China to cooperate. For China, fewer European and Asian investors means less competition for its companies in Iran and more access to Iranian energy. For Iran, China provides a coping mechanism amid international efforts to squeeze Tehran.

- China participated in nuclear talks with Iran along with Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States. A final deal was reached in 2015, which included sanctions relief for Iran. If implemented, it could have a positive impact on Beijing’s energy security and economic ambitions in the Middle East.

Overview

Iran and China established diplomatic relations in 1971, but trade started in 1950. Since 1982, Sino-Iranian economic and technological cooperation has progressed significantly. In 1985, they set up the Joint Committee on Cooperation of Economy, Trade, Science and Technology to collaborate on energy, machinery, transportation, building material, mining, chemicals and nonferrous metal.

Iran and China established diplomatic relations in 1971, but trade started in 1950. Since 1982, Sino-Iranian economic and technological cooperation has progressed significantly. In 1985, they set up the Joint Committee on Cooperation of Economy, Trade, Science and Technology to collaborate on energy, machinery, transportation, building material, mining, chemicals and nonferrous metal. The symbiotic Iran-China relationship dates to the early 1990s, when Beijing became a major oil importer. As Chinese economic growth accelerated, Beijing’s energy needs increasingly defined its political ties with Tehran. By 2015, Iran provided 11 percent of China’s oil imports. China was also the largest buyer of Iranian oil.

Trade between Iran and China soared from $4 billion in 2003 to over $20 billion in 2009, according to the International Monetary Fund. By 2013, it had doubled to $53 billion. China’s major exports to Iran have been machinery and equipment, textiles, chemical products and consumer goods. A significant portion of Chinese shipments has reportedly been funneled to Iran through China’s trade with the United Arab Emirates. China has also been selling refined gasoline to Iran, which lacks the refineries to meet its domestic needs.

China’s political shift

Premier Deng Xiaoping’s introduction of economic reforms in 1979 set the stage for a major transformation of China. Deng’s changes in the legal and political foundation of China’s economy gradually unleashed the Chinese people’s march toward a xiaokang (“well-being”) society, where the majority of the population has joined the ranks of the middle class through economic development. Deng promoted slogans like “To be rich is glorious” and “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice” to motivate his compatriots to use capitalist means to achieve socialist goals.

After major setbacks following Tiananmen Square in 1989, Chinese economic development began to gain momentum again in the early 1990s. In 1992, delegates to the 14th Communist Party Congress officially endorsed Deng’s renewed push for a market-oriented economy. China began to import oil after the influx of foreign investment, the growth of its export sector, and the expansion of the middle class. During this period, Beijing intensified efforts to secure energy resources from the Middle East. Commercial ties with Iran became a top priority. Beijing fed its increasing need for Iranian oil, while Tehran imported more Chinese manufactured goods.

Ayatollah Khamenei’s visit to Great Wall of #China during 1989 official visit. pic.twitter.com/CtEMpxBXl2

— Khamenei.ir (@khamenei_ir) January 23, 2016Commercial Ties

Growing commercial ties have significant strategic implications, with Beijing reaping the larger immediate benefits. China’s engine of economic growth is relatively well developed and maintained by a leadership group dominated by able technocrats. China, with a population of 1.3 billion, is improving the living standards of more of its citizens each year. Iranian oil helps keep this engine running. In contrast, Iran’s economy has contracted as a result of ineffective government policies. Sanctions have compounded—but not caused—this economic decline.

Tehran sees Beijing as a major trade partner and a key investor in Iran’s oil and gas fields, particularly in its outdated refiningcapabilities. The relationship has helped Iran’s economy withstand the impact of international sanctions that cut it off from most of the world.

At the same time, Iran’s economic difficulties—including an acute shortage of refined gasoline capabilities—have created unique opportunities for China. By 2015, China was highly dependent on foreign crude oil to meet its own energy needs. It even surpassed the United States as the world’s largest net oil importer. Iran – with the world’s fourth largest crude oil reserves – helps protect China’s energy security.

Beyond its oil resources, Iran plays an important role in China’s regional economic ambitions. Since 2013, China has pushed to expand its overland trade routes through the Silk Road Economic Belt, an initiative to build roads, railroads, and other transportation infrastructure throughout Central Asia. Iran is a critical part of this plan, due to its strategic location with access to key waterways.

Growing economic ties are also linked to strategic interests on both sides. Beijing and Tehran view each other as useful allies to counterbalance U.S. power in the Middle East. But China’s willingness to distance itself from the United States has its limits, as it relies on U.S. trade and investment to fuel its own economic growth. China also imports 16 percent of its oil from Saudi Arabia, a U.S. ally and one of Iran’s regional rivals.

International Sanctions

After a year of negotiations amid growing Iranian defiance, the Obama Administration secured Chinese and Russian support for the fourth round of U.N. sanctions on Iran in June 2010. U.N. Resolution 1929 restated the Council’s longstanding demand that Iran suspend its uranium enrichment activities and peacefully resolve outstanding concerns over the nature of its nuclear program. The additional sanctions primarily targeted Iran’s military and financial sectors.

In early August 2010, Chinese Vice Premier Li Keqiang reassured Iranian Oil Minister Massoud Mirkazemi that China would maintain cooperation with Tehran on existing large-scale projects in the energy sector, even after the United States directly called on Beijing to observe sanctions. With more than 100 Chinese state-owned enterprises operating in Iran, Beijing expanded its presence in the Iranian market and invested heavily in Iran’s energy sector. Gaps left by Western and other Asian firms forced out by sanctions presented Chinese companies with strategic opportunities to enlarge their share of key sectors amid reduced competition.

In early August 2010, Chinese Vice Premier Li Keqiang reassured Iranian Oil Minister Massoud Mirkazemi that China would maintain cooperation with Tehran on existing large-scale projects in the energy sector, even after the United States directly called on Beijing to observe sanctions. With more than 100 Chinese state-owned enterprises operating in Iran, Beijing expanded its presence in the Iranian market and invested heavily in Iran’s energy sector. Gaps left by Western and other Asian firms forced out by sanctions presented Chinese companies with strategic opportunities to enlarge their share of key sectors amid reduced competition. Washington imposed a new round of sanctions in 2012, which had a particularly damaging effect on Iran’s oil industry. China qualified for a U.S. waiver on Iranian crude oil purchases, but had to cut back imports. In 2012, China imported 20 percent less crude oil from Iran than in 2011. Sanctions disrupted development projects – China canceled a $4.7 billion project to develop the South Pars gas field in 2012. Sanctions also interfered with Chinese payments for crude oil purchases.

In November 2013, Iran and the world’s six major powers reached an interim deal over Iran’s controversial nuclear program. Tehran agreed to scale back some of its nuclear activities in exchange for limited sanctions relief. As a result, China’s imports of Iranian oil returned to pre-sanctions levels. China imported 28 percent more Iranian oil in 2014 than in 2013.

Beijing does not want Iran to acquire nuclear weapons, which could diminish China’s own nuclear status. But it also has incentives for a peaceful solution to the nuclear crisis. Around 52 percent of China’s oil imports come from the Middle East, and regional conflict – including an Israeli or U.S. military strike against Iran - could threaten to cut off oil transit routes.

After the final nuclear deal was announced in 2015, China quickly took steps to increase its trade and investment in Iran. “Those who were our friend during sanctions will receive our friendship to the same proportion,” said Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh.

Common regional interests

Two major trends in the growing Sino-Iranian relationship could help sustain cooperation between the two countries.

Caspian Sea: The first trend is China’s intensifying efforts to gain access to the energy resources of the Caspian Sea region. China’s major energy security initiative is to reduce its heavy reliance on maritime oil imports from Persian Gulf states. Iran is a linchpin in this Chinese regional strategy. Beijing’s plan to build pipeline access to the Caspian Sea region via Iran reinforces the symbiotic relationship between Tehran and Beijing. In this respect, China has a strong interest in seeing a secure Iranian regime.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization: The second trend is Iran’s increasing participation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). It was originally formed in 1996 to demilitarize the border between China and the former Soviet Union. It evolved into a wider regional organization after the Soviet Union’s break-up and the independence of Central Asian countries. Since 2005, Iran has had observer status in the SCO. In 2008, Tehran announced it would seek full SCO membership, but was rejected because Iran was subject to U.N. sanctions. After the nuclear deal was announced in 2015, SCO Secretary General Dmitry Mezentsev said that sanctions relief could pave the way for Iran’s full membership in the SCO.

Despite its limited activities, the SCO could provide Iran an organizational context to forge closer relations with states vital to its interests in Central Asia. Iran reportedly views the SCO as a potential guarantor of its future security.

Diplomacy

The regular exchange visits of senior Iranian and Chinese leaders highlight the mutual importance of bilateral relations. Iranian leaders who visited China include:

- Speaker of the Iranian Islamic parliament Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (June 1985)

- President Ali Khamenei (May 1989)

- Speaker Mehdi Karroubi (December 1991)

- President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (September 1992)

- First Vice-President Hassan Habibi (August 1994)

- President Mohammad Khatami (June 2000)

- President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (June 2006)

- President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (September 2008, June 2012)

- Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki (September 2008)

- First Vice President Parviz Davoodi (October 2008)

- First Vice President Mohammed Reza Rahimi (October 2009)

- Deputy Foreign Minister Mohammad Ali Fathollahi (December 2010)

- Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi (May 2011)

- Deputy Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian (January 2013)

- Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif (May, October 2014)

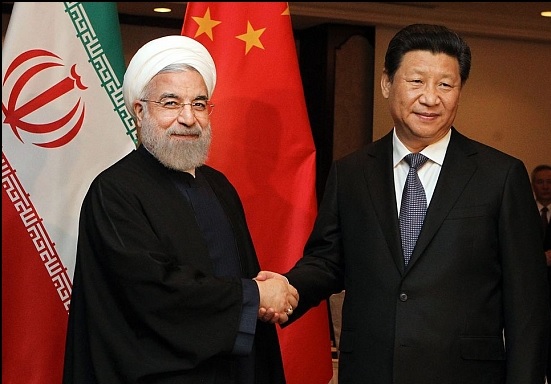

- President Hassan Rouhani (May 2014)

Chinese leaders who visited Iran include:

- Chairman of the National People’s Congress Wan Li (May 1990)

- Premier Li Peng (July 1991)

- President Yang Shangkun (October 1991)

- Chairman of the National People’s Congress Qiao Shi (November 1996)

- State Councilor Wu Yi (March 2002)

- President Jiang Zemin (April 2002)

- Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing (November 2004)

- Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi (November 2007)

- Vice Foreign Minister Zhai Jun (April 2008, August 2012)

- Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin (November 2010)

- Vice Foreign Minister Zhai Jun (December 2011)

- Foreign Minister Wang Yi (February 2015)

- President Xi Jinping (January 2016)

People's Republic of #China President Mr. Xi Jinping and his delegation met with Leader of Islamic Revolution. pic.twitter.com/Ybu7bfZEAz

— Khamenei.ir (@khamenei_ir) January 23, 2016Flashpoints

First: Trade Disputes

Tehran and Beijing have occasionally clashed over trade and the slow pace of investment projects, despite generally strong economic ties. In April 2014, Iran canceled a $2.5 billion contract with the China National Petroleum Corporation to develop the South Azadegan oil field after recurring delays on the project.

Iranians also blame the influx of cheap, low-quality Chinese goods for hindering domestic industrial development. In 2015, chairman of the Iran-China Chamber of Commerce Asadollah Asgarowladi acknowledged “minor differences” over the quality of Chinese products imported to Iran. “We believe that the quality of Chinese goods exported to Iran must be improved,” Asgarowladi said.

Second: China’s Muslims

Despite shared economic and geopolitical interests, Beijing and Tehran have clashed over China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang province. Tensions have risen between the wealthy Han majority and the Uighur minority as a result of Beijing’s efforts to promote Han migration to Xinjiang. In July 2009, ethnic riots erupted in the provincial capital of Urumqi after the killing of two Uighur workers in Guangdong province. More than 150 people were killed, 800 injured, and over 1,000 arrested. Most of those involved were Uighurs. Tehran sided with its Muslim brethren. Ayatollah Jafar Sobhani said, “In that part of the world, the unprotected Muslims are being mercilessly suppressed by yesterday’s communist China and today’s capitalist China.” And Iran’s Foreign Ministry expressed support for “the rights of Chinese Muslims.” A Chinese diplomat in Tehran countered that the Xinjiang riots were encouraged by foreign separatist groups and were not connected to religious or ethnic issues.

Despite shared economic and geopolitical interests, Beijing and Tehran have clashed over China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang province. Tensions have risen between the wealthy Han majority and the Uighur minority as a result of Beijing’s efforts to promote Han migration to Xinjiang. In July 2009, ethnic riots erupted in the provincial capital of Urumqi after the killing of two Uighur workers in Guangdong province. More than 150 people were killed, 800 injured, and over 1,000 arrested. Most of those involved were Uighurs. Tehran sided with its Muslim brethren. Ayatollah Jafar Sobhani said, “In that part of the world, the unprotected Muslims are being mercilessly suppressed by yesterday’s communist China and today’s capitalist China.” And Iran’s Foreign Ministry expressed support for “the rights of Chinese Muslims.” A Chinese diplomat in Tehran countered that the Xinjiang riots were encouraged by foreign separatist groups and were not connected to religious or ethnic issues.Both Iran and China sought to defuse tensions. Within days, an Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman said that Tehran balanced concerns for Muslims with bilateral relations with China. But Iranian concerns about China’s Muslim population continued to fester, despite a meeting between foreign ministry officials to discuss the ethnic unrest. Beijing’s approach to dealing with the Uighurs is likely to remain unchanged, endangering future ethnic unrest—and tensions with Tehran over a sensitive Chinese core interest.

Trendlines

- Beijing’s growing energy needs are likely to only deepen Iran-China relations for the foreseeable future. China’s oil demand has increased by an average of 5.7 percent annually between 2001 and 2014, and is expected to increase by 2.6 percentper year through 2020.

- China will likely remain a key investor in Iranian oil and gas infrastructure, as Beijing and Tehran intend to expand economic cooperation – especially after the nuclear deal is implemented.

John Park is an adjunct lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School and a research associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

This chapter was originally published in 2010. Cameron Glenn, a senior program assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace, contributed to an update of this chapter in 2015.

Photo credits: Rouhani and Xi Jinping via President.ir, Persian Gulf by Stevertigo at en.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons; Uighur mosque by Colegota via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 2.5]

PDF Iran Region_Park_China.pdf210.65 KB