Richard N. Haass

- The Bush administration’s policy on Iran was shaped largely by three factors: Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, American hostages held by Iranian allies in Lebanon and a new round of Arab-Israeli peace talks.

- The U.S. strategic priority after Iraq’s invasion was liberating Kuwait and making sure that Saddam Hussein could not dominate the oil-rich region. Iran was an indirect beneficiary of the war, which was a by-product of U.S. policy, but not an objective. The administration was mindful of the threat posed by Iran and worked to ensure any gains from Iraq’s defeat would be distinctly limited.

- The 1991 Madrid Peace Conference – the first face-to-face meeting between Israeli and Arab authorities – was a signal accomplishment for U.S. foreign policy. But Iran viewed it as a major threat to its regional standing and interests.

- Iran’s failure or inability to bring about the release of the American hostages held in Lebanon until mid-1991 (and its continuing support for acts of terrorism) squandered much of the “good will” offered in President Bush’s inaugural address.

Overview

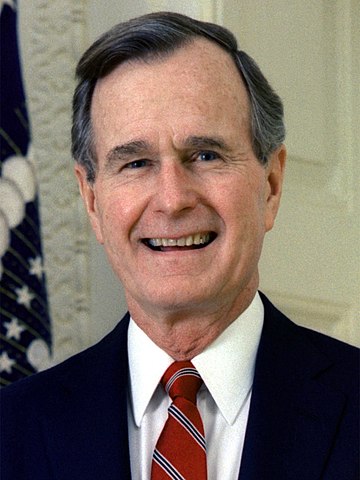

George H.W. Bush entered the White House during a period of rapid and historic global change. The main development was the end of the Cold War, which for four decades had been the defining feature of the international environment. This shift opened up possibilities for U.S.-Soviet – and, subsequently, U.S.-Russian—cooperation. It also muted competition even when cooperation proved elusive.

George H.W. Bush entered the White House during a period of rapid and historic global change. The main development was the end of the Cold War, which for four decades had been the defining feature of the international environment. This shift opened up possibilities for U.S.-Soviet – and, subsequently, U.S.-Russian—cooperation. It also muted competition even when cooperation proved elusive. The Cold War’s end loosened up the international system and increased the room for maneuver—in ways that at times were anything but benign—by other states and non-state entities. The Soviet Union’s demise helped create a moment in which U.S. primacy in the world was stark, a reality that led the 41st president to speak openly about a “new world order” based on stronger international institutions and a considerable degree of cooperation among states.

But the emergence of the United States as the world’s dominant power did not alter the decade-old tensions between Washington and Tehran. Hezbollah, the Lebanese militia sired and armed by Iran, had held several American and other Western hostages dating back to the mid-1980s. Since the late 1980s, Tehran had also aided the Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Hamas, who were challenging both Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization—and adding a new dimension to the conflict.

Early expectations

Ironically, the Middle East region was not expected to play a major role in the Bush 41 presidency. The one possible exception was trying to broker peace between Israel and the Palestinians and/or Syria. Iran and Iraq, the region’s principal contenders for power, had just ended eight years of brutal warfare. Sifting through the ashes of devastated cities, recovering from the hundreds of thousands of dead and wounded, and beginning the slow process of social and economic rebuilding would, it was presumed, preoccupy leaders in both countries.

The Bush administration, for its part, was at once distrustful of the Islamic Republic of Iran, yet open to improving relations. (One sign of this openness was President Bush’s telephone conversation in February 1990 with someone he believed to be Iranian President Akbar Rafsanjani, but who proved to be an imposter.) The continued holding of American hostages in Lebanon by Iranian-backed Hezbollah, however, cast a long shadow over U.S. relations with Tehran. Nevertheless, President Bush referred to the hostage situation in his 1989 inaugural address in a positive way. If Iranian assistance were to be shown, he said, it would not go unnoticed. “Good will begets good will. Good faith can be a spiral that endlessly moves on.”

Hostages released

The Bush administration worked quietly with and through the United Nations to gain the hostages’ release. There was some progress, but in the end, the hostage issue became another in the long line of missed opportunities between Washington and Tehran. Hezbollah had begun seizing Americans in 1982 and many had already languished in captivity for years. Lt. Col. William Higgins, who had been taken years earlier while serving in Lebanon with the United Nations, was killed in 1989.

Making matters worse from the American perspective was the 1989 fatwa issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini against Salman Rushdie, author of “The Satanic Verses.” His edict further limited potential for political progress, as did the assassination in August 1991, in Paris, of former Iranian Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar by Iranian agents.

The last American hostage was released in 1991, but by then the opportunity to improve U.S.-Iranian ties had largely disappeared. Iran’s leaders were reportedly angry and frustrated that their efforts to end hostage-taking did not meet with American goodwill, namely in a relaxation of sanctions or blaming Iraq for initiating the Iran-Iraq War.

From the American perspective, though, it was a case of too little, too late. Splits within Iran’s leadership, which had become more pronounced after the June 1989 death of Ayatollah Khomeini, may have made it impossible for Iran to release the hostages and end acts of terrorism. But what was behind the policy mattered less than the policy itself to officials in the Bush administration.

The Gulf War

Tehran’s commitment to exporting its revolution throughout the region, via its terrorist clients if necessary, remained an ongoing and serious threat to regional stability. A formal review of U.S. Persian Gulf policy, finalized in National Security Directive 26 and signed by the president in October 1989, reaffirmed the existing view that Iran, and not Iraq, posed the greater threat to U.S. interests in the region. As a result, President Bush supported a policy, which was consistent with what he inherited from President Reagan, of trying to build a political and commercial relationship with Iraq, in the hopes of moderating its behavior and offsetting Iranian power.

By the spring of 1990, the U.S. effort to work with Iraq was increasingly running up against the reality of Saddam’s bad behavior. What little was left of the policy of constructive engagement came to an end with Iraq’s August 1990 invasion and occupation of Kuwait. The strategic implications of Iraq’s actions were grave. If Saddam’s aggression was allowed to stand, an American diplomat noted at the time, “he would control the second- and third-largest proven oil reserves with the fourth-largest army in the world.” Saddam’s influence in OPEC’s decision-making on production levels and prices would be markedly greater, which would allow him to increase oil prices—and provide even larger revenues to spend on his military. Other states in the region would think twice before standing up to Iraq. Allowing Iraq to control Kuwait would also set a terrible precedent for international relations, setting back hopes that something better would emerge after the Cold War’s end.

For six months, from August 1990 through mid-January 1991, the United States and much of the world tried diplomacy and sanctions to persuade and pressure Saddam to withdraw Iraqi forces from Kuwait and accept its independence. All this made for an interesting moment for the U.S.-Iran relationship. The two countries had stumbled on a rare moment of seeming agreement.

The widespread international opprobrium, crippling economic sanctions and, eventually, military action against Iraq were weakening Iraq far more than Iran could ever hope to do alone. Moreover, Iran had to do little to help. It made some small contributions, such as grounding a significant number of Iraqi fighter jets that landed on its territory and largely respecting the embargo. But by and large, Iran’s leaders simply waited for the coalition to weaken its primary rival for regional power.

The degree of overlap between American and Iranian policy should not be exaggerated. The United States defeated Iraq but deliberately chose not to decimate it or march on to Baghdad. The administration calculated that an Iraq strong enough to balance Iran—but hopefully not strong enough to intimidate or conquer its Arab neighbors—was strategically preferable. U.S.-Iranian interests began to diverge even more clearly after the war. One reason the Bush administration mistrusted and opted not to aid the Shiite uprising in southern Iraq was because of Iranian involvement. Iran encouraged the uprising and sent Iranian-trained militias to join the rebels. Washington was concerned about long-term Iranian influence in Iraq.

Madrid Peace Conference

One of the Bush administration’s original goals in the Middle East was establishing formal peace talks among the Israelis, the Palestinians and their Arab neighbors. The timing was arguably even better after the Gulf War, given soaring U.S. prestige, the absence of a rival superpower, improved ties with many of the Arab states, and the weakening of the Palestine Liberation Organization after its decision to side with Iraq. It was a moment of unique American leverage.

The conference itself was unprecedented. President Bush and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev co-hosted the first face-to-face meetings between Israel and its Arab neighbors, including Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and the Palestinians. It began a years-long series of talks designed to secure a lasting and stable peace between old and wary enemies. To Iran, however, the Madrid summit also represented an unprecedented challenge.

The new peace process not only legitimized the existence of Israel—a state Iran viewed as an illegal and hostile imposition on the region—in the Arab world. It also threatened Iran’s ties with its most important allies. Syria, a participant in the Madrid Conference, was Iran’s principal ally in the region. A separate peace between Syria and Israel would remove a shared strategic goal and undermine the entire relationship. Hezbollah’s refuge in Lebanon could be similarly threatened by a deal between Lebanon with Israel. Disarming and potentially even disbanding Hezbollah would almost certainly have been among the terms of any agreement, an outcome that would remove much of Iran’s influence in the area.

The peace process spurred Iran’s support of a number of Palestinian terrorist groups, not least Hamas. It also encouraged cooperation among the groups, particularly Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Hezbollah. Tehran’s investments paid off, as a spate of fresh terror attacks in the Middle East and beyond shook efforts at peace. It also built relationships with Islamist movements across the Middle East, from Egypt and Algeria to the Gulf states and Lebanon, and invited these hostile forces to work against the peace process in general, and the United States and Israel, in particular.

The aftermath

- The U. S.–Iran relationship was largely stagnant during the Bush administration, with little contact and less progress.

- Iran and its support for terrorist groups posed a significant threat to efforts designed to promote peace and secure Israel’s place in the region.

- U.S. opposition to Iraq after Operation Desert Storm—a hostility that lingered for more than a decade until the 2003 war and Saddam Hussein’s removal—did not translate into better U.S. ties with Iran. In the Middle East, the enemy of your enemy can still be your enemy.

- Many of the same issues that had dogged U.S.-Iranian relations before President Bush took office in 1989—including differences about Israel, the use of terrorism as a tool of policy, and Iraq—were still problems when President Bush was succeeded by President Clinton.

Richard N. Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, was the National Security Council staff director in charge of the Middle East during the George H. W. Bush presidency.