Ali Alfoneh

- The Basij Resistance Force is a volunteer paramilitary organization operating under the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). It is an auxiliary force with many duties, especially internal security, law enforcement, special religious or political events and morals policing. The Basij have branches in virtually every city and town in Iran.

- The Basij have become more important since the disputed 2009 election. Facing domestic demands for reform and anticipating economic hardships from international sanctions, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has mobilized the Basij to counter perceived threats to the regime.

- The Basij’s growing powers have in turn increased the force’s political and economic influence and contributed to the militarization of the Iranian regime.

- Yet the Basij also face problems, reflected in their poor handling of the 2009 protests, limited budget and integration into the IRGC Ground Forces in July 2008. Targeted U.S. and international sanctions against the IRGC could further weaken the Basij.

Overview

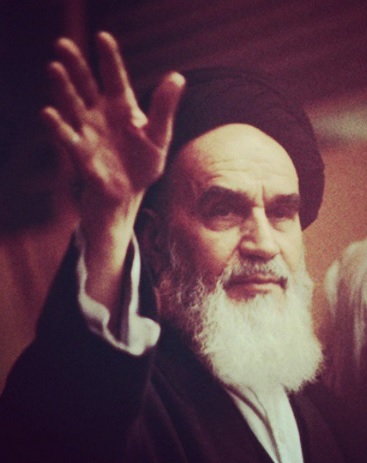

On November 25, 1979, revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini called for the creation of a “twenty million man army.” Article 151 of the constitution obliges the government to “provide a program of military training, with all requisite facilities, for all its citizens, in accordance with the Islamic criteria, in such a way that all citizens will always be able to engage in the armed defense of the Islamic Republic of Iran.” The “people’s militia” was established on April 30, 1980. Basij is the name of the force; a basiji is an individual member.

On November 25, 1979, revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini called for the creation of a “twenty million man army.” Article 151 of the constitution obliges the government to “provide a program of military training, with all requisite facilities, for all its citizens, in accordance with the Islamic criteria, in such a way that all citizens will always be able to engage in the armed defense of the Islamic Republic of Iran.” The “people’s militia” was established on April 30, 1980. Basij is the name of the force; a basiji is an individual member.The Basij were initially engaged in assisting the Revolutionary Guards and the Revolutionary Committees (disbanded in the early 1990s) to secure law and order in major population centers. The auxiliary military unit also aided the central government in fighting against Baluchi, Kurdish and Turkoman separatists in remote regions. But their role shifted after Iraq’s 1980 invasion. As the war took its toll on Iranian forces, the poorly trained Basij were deployed alongside the regular Iranian military. They were often used in “human wave” tactics, in which they were deployed as cannon fodder or minesweepers, against Iraqi forces. Mobilization of Basij for the war-front peaked in December 1986, when some 100,000 volunteers were on the front. The Basij were often criticized for mobilizing child soldiers for the war effort and using children for “martyrdom” operations.

After the war ended in 1988, the Basij became heavily involved in post-war reconstruction. But their role increasingly shifted back to security as a political reform movement flowered in the late 1990s. The Basij became a policing tool for conservatives to check the push for personal freedoms, particularly among students and women. The Basij were mobilized in 1999 to put down anti-government student protests and to further marginalize the reform movement.

Since the 2005 election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Basij interventions in politics have become more frequent. The Basij were pivotal in suppressing the anti-government protests after the disputed presidential election on June 12, 2009. Various branches of the Basij were mobilized to counter anti-government protests at high schools, universities, factories and on the street. Yet the Basij also performed poorly, as they were unable to suppress demonstrations through their local branches. The Iranian press reported that neighborhood Basij were not willing to beat up neighbors who protested against the election result by chanting “God is great” from their homes. Some Basij members at high schools and universities also reportedly deserted their assignments after commanders chiefs tried to mobilize them to intimidate, harass or beat up fellow students engaged in sit-ins and demonstrations against the election results. And many Basij members evaporated in the face of angry demonstrators in major population centers. Basij and IRGC commanders reported transporting Basij members from outside towns to counter dissidents as the local Basij members were not ready to act in their own neighborhoods or place of work.

Mission and command

The Basij statute stipulates that the militia’s mission is to “create the necessary capabilities in all individuals believing in the Constitution and the goals of the Islamic Republic to defend the country, the regime of the Islamic Republic, and aid people in cases of disasters and unexpected events.”

The Basij organizational structure divides each city in Iran—depending on its size and population—into “resistance areas.” Each resistance area is then divided into resistance zones, each zone into resistance bases, and each base into several groups. The smaller towns and villages have Basij “resistance cells.” Sensitive social housing areas, such as housing for members of the regular army, also appear to have a special Basij presence. The Revolutionary Guards and the regular military are effectively rivals for resources, equipment and power.

Branches

The Basij has several branches. There are three main armed wings:

- Ashoura and Al-Zahra Brigades are the security and military branch tasked with “defending the neighborhoods in case of emergencies.”

- Imam Hossein Brigades are composed of Basij war veterans who cooperate closely with the IRGC ground forces.

- Imam Ali Brigades deal with security threats.

The force also has multiple branches with specialized functions. They include:

- Basij of the Guilds [Basij-e Asnaf]

- Labor Basij [Basij-e Karegaran]

- Basij of the Nomads [Basij-e ‘Ashayer]

- Public Servants’ Basij [Basij-e Edarii]

- Pupil’s Basij [Basij-e Danesh-Amouzi]

- Student Basij [Basij-e Daneshjouyi]

Each specialized branch of the Basij functions as a counterweight to non-governmental organizations and the perceived threat they pose to the state. Basij of the Guilds, for example, is a counterpart to professional organizations. The Labor Basij provides a counterpart to labor organizations, unions and syndicates. And the Student Basij balances independent student organizations.

Membership

Estimates of the total number of Basij vary widely. In 2002, the Iranian press reported that the Basij had between 5 million to 7 million members,although IRGC commander Gen. Yahya Rahim Safavi claimed the unit had 10 million members. By 2009, IRGC Human Resource chief Masoud Mousavi claimed to have 11.2 million Basij members—just over one-half the number originally called for by Khomeini. But a 2005 study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think-tank, put the number of full-time, uniformed and active members at 90,000, with another 300,000 reservists and some 1 million that could be mobilized when necessary. Persian language open-source material does not provide any information about what percentage of the force is full time, reservists or paid members of the organization.

Members include women as well as men, old as well as young. During the Iran-Iraq War, Basij volunteers were as young as 12 years old, with some of the older members over 60 years old. Most today are believed to be between high school age and the mid-30s. The perks can include university spots, access to government jobs and preferential treatment.

The Basij statute distinguishes between three types of members:

- Regular members, who are mobilized in wartime and engage in developmental activities in peacetime. Regular members are volunteers and are unpaid, unless they engage in war-time duty.

- Active Members, who have had extensive ideological and political indoctrination, and who also receive payment for peacetime work.

- Special Members, who are paid dual members of the Basij and the IRGC and serve as the IRGC ground forces.

The Basij statute says members are selected or recruited under the supervision of “clergy of the neighborhoods and trusted citizens and legal associations of the neighborhoods.” The neighborhood mosques provide background information about each volunteer applicant; the local mosque also functions as the Basij headquarters for the neighborhood. For full-time paid positions, applicants must apply at central offices of the Basij, in provincial headquarters of the Basij.

Budget and business

The Basij’s budget is modest. According to the 2009/2010 national budget, the Basij were allocated only $430 million – or less than $40 per member, on the basis of 11.2 million members. But as a corporation, the Basij reportedly accumulated vast sums through so-called interest-free financial institutions that the Basij and the IRGC established in mid-1980s and the early 1990s to provide social housing and general welfare to their members. As subsequent governments began privatization of publicly owned enterprises, Basij financial institutions used their funds to purchase the privatized companies.

By 2010, the Basij were allegedly a major investor in the Tehran Stock Exchange. The largest Basij-owned investors in the Tehran Stock Exchange allegedly include Mehr Finance and Credit Institution, and its subsidiary Mehr-e Eghtesad-e Iranian Investment Company. Iranian critics of the Basij accuse them of distorting the market, marginalizing not only the private sector, but also the revolutionary foundations that have been a large part of Iranian economy since the revolution. The Basij and the IRGC are also accused of widespread corruption.

Political role

Presidential contender Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of parliament, accused the Basij and the Revolutionary Guards of helping manipulate the outcome of the 2005 election, when Ahmadinejad defeated former President Rafsanjani. Karroubi and Mir-Hossein Mousavi raised similar allegations against the Basij after the disputed June 12, 2009 presidential election.

Presidential contender Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of parliament, accused the Basij and the Revolutionary Guards of helping manipulate the outcome of the 2005 election, when Ahmadinejad defeated former President Rafsanjani. Karroubi and Mir-Hossein Mousavi raised similar allegations against the Basij after the disputed June 12, 2009 presidential election.The Basij's performance since the June 2009 election has been mixed. It managed to suppress street protests in the provinces with the help of the local police forces, but maintaining order in major urban centers, especially Tehran, was more difficult. And their actions have faced backlash. On June 15, Basij members reportedly shot and killed protesters at Azadi Square who were forcing their way into the local militia station. From June 22 onward, the Basij constituted only a minority of the forces cracking down on protesters. Basij commander Hossein Taeb, a Shiite cleric with the rank of hojatoleslam, claimed that eight Basij had been killed and 300 wounded during the anti-government protests.

The Student Day protests in December 2009 proved equally challenging for the Student Basij, who had mobilized several thousand members but were still unable to suppress dissidents at campuses in Tehran, Shiraz and Tabriz. The Basij were also unable to contain the massive demonstrations three weeks later during Ashoura, the holiest time of the year for Shiite Muslims. Senior military officials admitted that the IRGC had to mobilize militia members from the capital's outskirts and even from other provinces in order to suppress the unrest.

The regime signaled its displeasure with the Basij's performance. In October 2009, Taeb was removed as Basij chief. A few days later, the militia was formally integrated into the Revolutionary Guards ground forces, with Brig. Gen. Mohammad Naghdi as the new chief. In 2010, the Basij focused significant attention on combating perceived threats to the regime from the Internet. Thousands of members were educated in blogging and filtering of dissident websites, Basij officials acknowledged.

Trendlines

- Without a solution to Iran’s internal political turmoil, the Basij’s role and powers are almost certain to grow.

- But because they receive less training than other Iranian security forces, their tactics are often the toughest against dissidents—and in turn generate more public anger that could weaken rather than strengthen the regime long-term.

- Incorporating the Basij into the Revolutionary Guards ground forces may improve the overall Basij performance in the future, but in the short- and middle-term, the IRGC and not the Basij are likely to remain the main pillar of support for the regime.

Ali Alfoneh is a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

This chapter was originally published in 2010. The following are updates as of 2015.

The Basij have reportedly supported Iran’s activities in Iraq and Syria since 2011. In June 2014, an Iraqi official said that 1,500 Basij forces had entered Iraq’s Diyala province, and another 500 entered the Wasat province. And as of mid-2015, experts estimate that 7,000 Revolutionary Guard and Basij members are active in Syria. Their primary role has been to help train militias supporting Syrian President Bashar al Assad.

Since 2010, the United States has imposed sanctions against the Basij and some of its officials, including Commander Mohammad Reza Naqdi, Deputy Commander Ali Fazli, and former Commander Hossein Taeb.

PDF Military_Alfoneh_Basij.pdf201.21 KB