Alireza Nader

Iranian politics are personal. Indeed, the theocrats are decidedly earthly in their rivalries. But the 2013 election is particularly telling. It may be settling a score dating back a quarter century between the revolution’s two most enduring politicos—Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

The two men have competed for power and the right to define the revolution since the death of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989. Rafsanjani originally had the upper hand in two sweeping changes. He oversaw constitutional changes that created an executive president, which he then ran for and won. And, in Tehran’s worst-kept secret, he orchestrated Khamenei’s selection as the new supreme leader, reportedly because Khamenei was a middle-ranking cleric and dour figure who could not rival Rafsanjani’s political base or charismatic wiles. Khamenei actually owes his power and position to Rafsanjani, the man known in Iran as the “shark.”

The two men have competed for power and the right to define the revolution since the death of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989. Rafsanjani originally had the upper hand in two sweeping changes. He oversaw constitutional changes that created an executive president, which he then ran for and won. And, in Tehran’s worst-kept secret, he orchestrated Khamenei’s selection as the new supreme leader, reportedly because Khamenei was a middle-ranking cleric and dour figure who could not rival Rafsanjani’s political base or charismatic wiles. Khamenei actually owes his power and position to Rafsanjani, the man known in Iran as the “shark.” But since 1989, Rafsanjani’s master plan has gradually unraveled. In 2013, Khamenei has now managed not only to emerge from Khomeini’s shadow. He has also sidelined most of his old rivals, including the crafty Rafsanjani. On May 21, Rafsanjani was disqualified from running for the presidency—even though the 12-man Guardian Council had qualified him to run in three earlier elections. He had been elected twice. Rafsanjani is 78. Winning elected political office is likely to be increasingly difficult. Hardliners in parliament even considered legislation this year that would bar any candidate over the age of 75.

For now, Khamenei is his own man. Yet the two rivals still epitomize a core schism among the original revolutionaries.

Rafsanjani believes Islam should be the basis of Iran’s political system. But he also advocates facets of modern politics, including republican institutions, an essentially capitalist economy, and a foreign policy that honors international practices. It is not liberal democracy. It instead has electoral outlets with strict safeguards that protect religious and revolutionary doctrines. Rafsanjani appears to view himself as a modern day version of Amir Kabir, the reformist chief vizier for Qajar dynasty Naser al Din Shah in the 19th century.

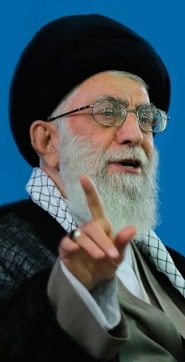

In contrast, Khamenei is more conservative and dogmatic. He believes that the supreme leader, rather than the president, should be the theocracy’s key decision-maker. He also appears to view the Iranian people more as subjects than citizens. For Khamenei, the supreme leader’s authority is primarily derived from God and the Hidden Imam. Elected institutions are meant to implement his policies rather than shape them.

Khamenei has spent the last 24 years converting his vision into a reality—and taking on his revolutionary peers. Between 1989 and 1997, he tolerated President Rafsanjani’s economic liberalization and attempted détente with the West because he had little choice as a newly minted leader. But he used the time to build his own power base, tapping into close connections to the Revolutionary Guards. He had served as their supervisor and deputy minister of defense during the revolution’s first decade and the tough eight-year war with Iraq.

Once Rafsanjani’s term was over, Khamenei used the Guards to suppress reformists under President Mohammad Khatami, who held office for two terms between 1997 and 2005. Khamenei was widely believed to feel threatened by Khatami, a suave cleric who had popular appeal and a historic connection to Khomeini. Like Rafsanjani, Khatami was also thwarted from running again in the 2013 presidential election.

Khamenei’s initial support for Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who first ran for the presidency in 2005, was partly because the Tehran mayor’s had no connections to Khomeini. He was also not a cleric with religious standing that could undermine the supreme leader. The other two major candidates in the disputed 2009 presidential race — Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi — had both been close to Khomeini. As prime minister from 1981 to 1989, Mousavi had frequently clashed with Khamenei at a time Iran had a parliamentary government and Khamenei was titular president. Karroubi had been head of the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee and the Martyr's Foundation as well as speaker of parliament. Both men are now under house arrest for challenging the 2009 election and serving as leaders of the so-called “sedition” against Khamenei’s rule.

Khamenei has managed to clear the field. Yet his position at the top is also lonely and potentially unwieldy.

Ironically, Iran’s supreme leader now faces opposition from an unexpected source — the family of the only other man who held the job. Khomeini’s daughter recently published an open letter to Khamenei stating that her father wanted Iran to be ruled by Khamenei and Rafsanjani working side-by-side. She warned that Rafsanjani’s removal from power would make the regime a dictatorship — and could even imperil the revolution.

Alireza Nader is a senior policy analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and the author of “Iran After the Bomb.”

Read Alireza Nader's chapter on the Revolutionary Guards in "The Iran Primer"

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org