Stephen J. Hadley

- The Bush administration’s engagement with Iran began positively. The two nations worked together to form a new Afghan government after the 2001 ouster of the Taliban.

- But efforts to cooperate on Iraq after Saddam Hussein’s overthrow foundered. Iran increasingly provided training, weapons and support to terrorists and insurgents, first in Iraq and later in Afghanistan.

- U.S. and international concern about Tehran’s nuclear activity increased dramatically in 2002, when an exile group revealed that Iran had secretly built a facility in Natanz capable of enriching uranium for use in nuclear weapons as well as civilian nuclear power reactors.

- After Iran reneged on an agreement to suspend uranium enrichment in 2005, the White House backed an international campaign offering Iran a choice: aid and engagement or economic pressure. Tehran balked.

- As part of its “freedom agenda,” the administration supported greater political opening in Iran through presidential speeches, Persian language broadcasts and aid to civil society groups.

Overview

The Bush administration had perhaps the most significant public engagement with Iran since the 1979 revolution, mainly on Afghanistan and Iraq. But it was short-lived. Iran’s growing support for extremist groups and new revelations about its secret nuclear facilities soon produced some of the deepest tensions between Washington and Tehran since relations originally ruptured.

The Bush administration had perhaps the most significant public engagement with Iran since the 1979 revolution, mainly on Afghanistan and Iraq. But it was short-lived. Iran’s growing support for extremist groups and new revelations about its secret nuclear facilities soon produced some of the deepest tensions between Washington and Tehran since relations originally ruptured. On Iran’s nuclear program, Bush administration strategy was to rally the international community to confront the Iranian regime with a strategic choice. Tehran could transparently and verifiably give up its pursuit of a nuclear weapons capability, especially its enrichment facility at Natanz. If it did, the international community would respond with substantial diplomatic, economic and security benefits. These would include the relaxation of existing economic sanctions and active international support for a truly peaceful civilian nuclear program, including the supply of nuclear fuel so Iran would not need an enrichment facility. If it rejected this choice, the regime would only be further isolated diplomatically, incur increased economic sanctions, and run the risk of military action.

The Bush approach can be summarized as the “two clocks” strategy: First, try to push back the time when the Iranian regime would have a clear path to a nuclear weapon. And second, try to bring forward the time when public pressure would either cause the regime to change its nuclear policy (and suspend enrichment), or transform it into a government more likely to make the strategic choice to deal with the international community.

Engaging Iran

The Bush administration was aware of Clinton administration efforts to engage the Iranian regime and improve relations. But the lack of a sustained positive response from President Mohammad Khatami was taken by the Bush administration as evidence that he was either unable or unwilling to deliver. Despite skepticism engendered by this history, the Bush administration engaged the Iranian regime after the 9/11 attacks. Tehran had long backed the Northern Alliance, the main Afghan opposition force, which Washington also supported to help oust the Taliban. U.S. and Iranian envoys then worked together at the Bonn conference in December 2002 to establish the first post-Taliban government in Afghanistan. The Iranian team was pivotal in convincing the Afghan opposition to support the U.S.-backed candidate for president, Hamid Karzai.

After the 2003 ouster of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, Tehran and Washington again sought to cooperate to stabilize Iraq internally in the face of increasing terrorist and insurgent violence. In 2004, U.S. and Iranian envoys held three meetings in Baghdad, two at ambassadorial level. But little was accomplished. In the years that followed, diplomatic engagement on Iraq and Afghanistan went downhill. Iran increasingly trained, armed, and aided Shiite extremists in Iraq and later Taliban militants in Afghanistan. Other engagement efforts had little merit or success. In 2003, a fax purportedly from Iranian sources offering a diplomatic breakthrough arrived on a State Department fax machine. It was later determined to be the result of freelancing by a Swiss diplomat hoping to be the one to make peace between Iran and the United States.

Terrorism

Iran continued throughout this period to support other terrorist groups such as Hezbollah, Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Hamas. Tehran provided them with increasingly advanced weaponry, all for use against Israel. Iran’s support contributed to both the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon (sparked by the kidnapping of Israeli soldiers) and the 2008 Israeli incursion into Gaza (in response to rocket attacks launched from Gaza into Israel). The Bush administration staunchly defended Israel’s right to defend itself against these terrorist threats, while at the same time using its diplomacy to extricate Israel from each of these conflicts.

The Bush administration considered Hezbollah the “A-team” of terrorist groups. It had killed and kidnapped Americans during two previous administrations. The White House took steps to enhance U.S. capability to deal with this threat. But Hezbollah did not undertake terrorist activity directed against Americans or provoke a confrontation with the United States during President Bush’s tenure.

“Axis of evil”

The Bush administration placed a high priority on fighting terrorism and countering nuclear proliferation. The scope and sophistication of the al Qaeda attack on September 11, 2001 increased concern that these two dangers would merge, and nuclear terrorism would pose an even more ominous threat. Iran was one of three countries—with Iraq and North Korea—that sponsored terrorist groups and were widely believed to be pursuing nuclear weapons.

President Bush sought to dramatize this risk in his State of the Union speech on January 29, 2002. He called these three states “an axis of evil,” because each represented a potential link between terrorists and weapons of mass destruction. The administration was criticized for using the word “axis,” suggesting a World War II-style alliance among these three states and sounding as if Washington was threatening them with war. The criticism colored how the speech was received, particularly abroad, and gave it a war-mongering cast. Yet, the speech did not prevent the subsequent constructive cooperation between the United States and Iran on Afghanistan

Nuclear deal

After revelations about Iran’s secret nuclear sites, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) pressed Tehran in 2002 and 2003 for greater access, particularly to the Natanz uranium enrichment facility. It sought answers to outstanding questions about the regime’s nuclear program and called on the regime to suspend all further enrichment activity. About the same time, Britain, France and Germany—the EU-3—sought to engage Iran in a political dialogue.

In October 2003, the EU-3 foreign ministers and Iranian officials in Tehran issued a statement in which Iran agreed to cooperate fully with the IAEA and voluntarily suspend all uranium enrichment activities. It separately agreed to provisional implementation of the IAEA Additional Protocol, which gave the IAEA enhanced access to Iran’s nuclear-related facilities. The statement was codified in the Paris Agreement signed on November 14, 2004, after a year of attempted Iranian backpedaling. In support of EU-3 diplomacy, the United States announced in March 2005 that it would drop its objection to Iranian membership in the World Trade Organization and consider licensing spare parts for aging Iranian civilian aircraft.

Nuclear setback

After he took office in 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad promptly accused Iranian diplomats who had negotiated the Paris Agreement of treason, and began to restart Iran’s nuclear activities. In April 2006, Tehran announced that uranium enrichment had resumed at Natanz.

The administration did not give up on efforts to engage the regime. It backed international overtures, including an EU offer in August 2005 to provide extensive, long-term political, economic and civilian nuclear cooperation, if Tehran suspended enrichment. It supported Moscow’s plan to enrich fuel in Russia for Iran’s new nuclear power reactor at Bushehr and then take back the spent fuel rods to ease international concern about the reactor.

The White House also extended its own offer. In May 2006, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice announced that the United States would join the EU-3’s talks with Iran once Tehran suspended all enrichment-related activities. The next month, the so-called P5+1 offered additional incentives. (The P5+1 included the five permanent U.N. Security Council members—Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States—plus Germany.) EU foreign policy chief Javier Solana launched a series of meetings with Iranian nuclear negotiator Ali Larijani. But whenever they seemed to be making progress, Ahmadinejad publicly attacked the process. In 2007, Larijani resigned in frustration. A final P5+1 diplomatic effort offered a “refreshed” incentives package in Geneva in 2008, with U.S. Under Secretary of State William Burns in attendance. It went nowhere. The Iranian regime gradually expanded its nuclear activities.

Sanctions

As Iran balked, the administration and its European allies won international support for a sequence of four separate U.N. Security Council resolutions: 1737, 1747, 1803 and 1835. They sanctioned Iranian missile and nuclear-related entities and persons, imposed asset freezes and travel bans, and required international vigilance regarding arms sales to Iran. Separately, the United States unilaterally sanctioned the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Iranian state-owned banks. Sanctioning official Iranian government entities sent a signal of increased seriousness, and including the IRGC meant attacking a principal security pillar of the regime – and the one it relied upon to keep the Iranian people in line.

The administration also launched a unique global campaign to get major foreign banks to stop doing business with Iran because it violated international banking practices. The Treasury Department convinced banks and later multinational businesses that dealing with Iranian banks or supplying goods and services to the government carried reputational risks, due to the potential that these entities engaged in any of three practices: Facilitating nuclear proliferation, supporting terrorism, or money laundering needed to finance these activities. More than 90 major international banks in dozens of countries signed on. The combination of economic sanctions and banking restrictions led major multinational companies to pull out of contracts with the Iranian government. The international Financial Action Task Force and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development later issued their own warnings about dealing with Iranian financial institutions.

National Intelligence Estimate

In 2007, the Director of National Intelligence released the unclassified judgments of a National Intelligence Estimate confirming that Iran had had a covert program to develop nuclear weapons. The program included covert nuclear weapon design, weaponization (including marrying a nuclear warhead with a ballistic missile delivery system) and uranium enrichment-related work. The NIE judged this covert work to have been suspended in the fall of 2003 at roughly the same time that Iran agreed to suspend its overt enrichment activity at Natanz. The release of the NIE judgments seriously set back Bush administration efforts during 2008 to convince the international community to impose further sanctions on Iran.

The NIE concluded that the covert program “probably was halted in response to international pressure.” Other events in 2003— the U.S. invasion of Iraq over its suspected nuclear weapon activities, and the interception of the German cargo ship BBC China carrying uranium enrichment centrifuge components to Libya—may have helped convince the Iranian regime that its covert program was too risky. (Libya ended up handing over all elements of its nuclear weapon and other weapons of mass destruction programs to the United States.) When the Bush administration left office, there were questions about whether Iran’s covert nuclear weapons activities remain suspended.

U.S. support for Iranian freedom

Over this period the Iranian regime increasingly pursued a more repressive policy at home, sidelining reformers and pragmatists and cracking down on regime opponents. The Bush administration wanted to show that it stood with the Iranian people, but without discrediting Iranian political activists or subjecting them to the charge of being American agents. Washington had to deal with the Iranian regime diplomatically but without enhancing its legitimacy.

The administration sought to strike the right balance in several ways. In presidential speeches and other statements, it made a distinction between the Iranian people (which it supported) and the regime (which it challenged to give its people more political freedom). Senior officials blamed regime policies for the isolation and hardships suffered by the Iranian people. President Bush spoke directly to the Iranian people on the Iranian new year, expressing respect for Iranian history, culture and traditions, and explicitly expressing American support for their struggles.

In 2002, the United States began to increase the flow of news and information into Iran. The Voice of America (VOA) established what later became its Persian News Network (PNN). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and VOA jointly established Radio Farda. For the 2003 Afghan election and the 2005 Iraqi vote, provisions were made so that refugees of both countries living in Iran would be able to vote in their nation’s respective elections. It was hoped that their example would encourage Iranians to demand more free and fair elections from the Iranian regime. In 2008, Congress appropriated $60 million for programs to promote democracy, the rule of law and governance in Iran.

The aftermath

- The Bush administration added to the long history of attempted engagement with Iran, having some initial success, but growing disillusioned over time as Iran failed to respond positively.

- The administration left behind a robust international framework for coordinating incentives to encourage positive behavior from the Iranian regime, as well as diplomatic and economic pressure if it failed to comply with U.N. resolutions.

- The administration developed a new set of tools to exert economic pressure by cutting off Iran from the international financial system and persuading multinational businesses to sever ties with the regime.

- The administration enhanced the U.S. military presence in the Middle East, encouraged and facilitated increased defense cooperation among Arab allies—on air defense, missile defense and in other areas—and worked to enhance the defense capabilities of individual friends and allies.

- As the Bush administration left office, there was increasing debate within Iran about the wisdom of the regime’s foreign policy, its economic performance and the lack of political freedom.

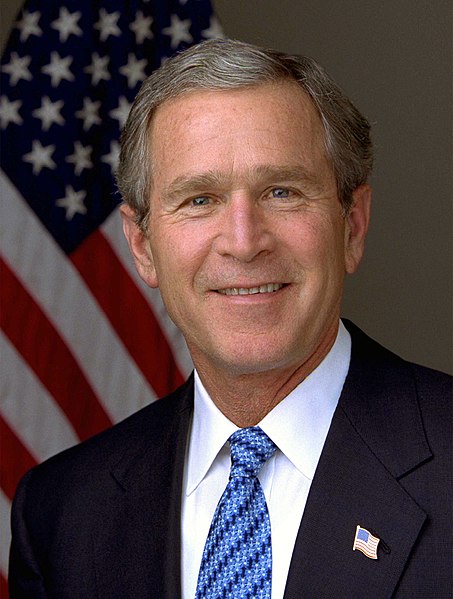

Stephen J. Hadley was national security adviser for President George W. Bush during his second term, and assistant secretary of defense under President George H.W. Bush. He is currently senior advisor for international affairs at USIP.