Michael Eisenstadt

- A long, porous border and extensive political, economic, religious and cultural ties provide Iran the potential for significant influence in Iraq.

- Iranian attempts to wield influence, however, have often backfired, leading to a nationalist backlash by Iraqis and tensions with the Iraqi government.

- The U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 allowed Iran to enhance its influence, attempting to incorporate Iraq into the “axis of resistance.”

- The rise of the so-called “Islamic State” has created a new opportunities for Iran to expand its influence in Iraq and to present itself as the country’s savior.

Overview

Since ancient times, Iraq and Iran have been the seats of rival states and empires. Mesopotamia, today’s Iraq, was home to the Assyrian, Babylonian and medieval Abbasid empires. The Achaemenid, medieval Safavid and early-modern Qajar dynasties ruled in Persia.

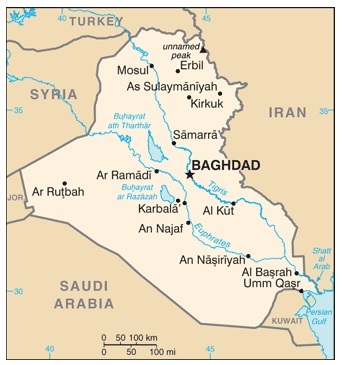

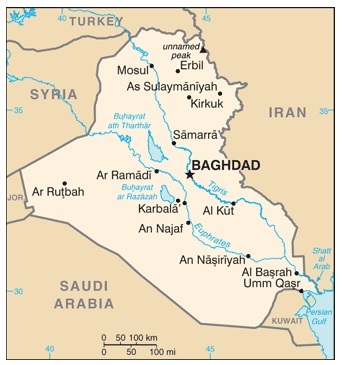

Iraq has also held special significance for Iran ever since the Safavid dynasty made Shiism the state religion in the 16th century. Shiite Islam was born in Iraq. The holy Shiite cities of Najaf and Karbala are traditional Shiite centers of learning and destinations for religious pilgrims. For centuries, the holy cities have had a strong Persian presence. As a result, Iran views southern Iraq as part of its historic sphere of influence.

This ancient rivalry has continued into modern times. The newly established Islamic Republic tried to export its Islamic ideology to Iraq, providing Saddam Hussein a pretext for his 1980 invasion. The Iraqi leader in turn tried to strike a fatal blow against his foremost regional rival and to seize its oil wealth. Instead, the invasion produced a long, bloody and inconclusive eight-year war that killed and wounded well over 1 million people.

The toppling of Saddam Hussein in 2003 by U.S. and coalition forces thus constituted an historic opportunity for Iran to expand its influence in Iraq, and to transform it from an enemy into a partner or ally. And the establishment of the so-called “Islamic State” – also known as ISIS, ISIL, or Daesh – in northern and western Iraq in 2014 allowed Iran to enhance its influence in Baghdad and present itself as Iraq’s protector. As of 2015, whether it could succeed in these goals remained to be seen.

Political strategy

Since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iran has tried to influence Iraqi politics by working with Shiite and Kurdish parties to create a weak federal state dominated by Shiites and amenable to Iranian influence. Tehran has also supported Shiite insurgent groups and militias, and enhanced its soft power in the economic, religious and informational domains.

Iran’s strategy has been to unite Iraq’s Shiite parties so that they can translate their demographic weight into political influence, thereby consolidating Shiite primacy in the Baghdad. Tehran encouraged its closest allies—Badr, the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), Dawa and the Sadrists to participate in politics and help shape Iraq’s nascent institutions. It has backed a range of disparate parties and movements to maximize its options and ensure its interests are advanced, no matter which Iraqi party came out on top.

Local allies

The Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) was established in Tehran in 1982 by expatriate Iraqis, and was based there until returning to Iraq in 2003. Its militia, the Badr Corps, was trained and controlled by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and fought alongside Iranian forces during the Iran-Iraq War. After 2003, thousands of Badr militiamen entered southern Iraq from Iran to help secure that part of the country. Many were subsequently integrated into the Iraqi security forces, particularly the army and the national police. Ammar al Hakim has led ISCI since the death of his father, Abd al Aziz al-Hakim, in 2009.

The Badr Organization split from ISCI in 2012, and has since operated as an independent party. After the fall of Mosul to ISIS in June 2014, Badr and its leader, Hadi al Amiri, have spearheaded the military campaign against ISIS, greatly increasing the organization’s domestic political profile. As of 2015, Hadi al Ameri was one of Tehran’s closest allies in Iraq.

Dawa, founded in the late 1950s, enjoyed the Islamic Republic’s support during the latter phase of its underground existence in Iraq. After 2003, Dawa joined the political process, but its potential was limited due to its lack of an armed militia. Its leader, Nuri al-Maliki, was selected by the more powerful ISCI and Sadrists as a compromise choice for prime minister in 2005, but he subsequently used this position to build a power base in the government and the army—parts of which functioned as a personal and party militia. Following the 2014 elections, Maliki was replaced as prime minister by another Dawa member, Haidar al Abadi.

Maliki shared a general affinity with Tehran’s Shiite Islamist worldview, but not its doctrine of clerical rule. Mindful of his dependence on Washington for survival, he tried to tread a middle path between Tehran and Washington, and avoided a full-fledged embrace of Tehran.

Abadi, who spent his years in exile in the United Kingdom, represented a less insular tendency within the party. He continued Maliki’s policy of trying to hew a middle path between Washington and Tehran, while calling for reconciliation with Iraq’s Sunni Arab community. But the influence of sectarian elements within his State of Law Coalition and the ruling Iraqi National Alliance prevented him from implementing this agenda.

Abadi, who spent his years in exile in the United Kingdom, represented a less insular tendency within the party. He continued Maliki’s policy of trying to hew a middle path between Washington and Tehran, while calling for reconciliation with Iraq’s Sunni Arab community. But the influence of sectarian elements within his State of Law Coalition and the ruling Iraqi National Alliance prevented him from implementing this agenda.

The Sadrists have emerged as a major force in politics and the Iraqi street since 2003. Their leader, Muqtada al Sadr, has played on his family name as the sole surviving son of the revered Ayatollah Muhammad Sadiq al Sadr, who was murdered by regime agents in 1999. His populist, anti-American rhetoric, and the muscle and patronage offered by his Jaysh al Mahdi (Mahdi Army) militia, recently renamed the Saraya al Salam (Peace Companies), have gained him support among the Shiite urban poor.

Though politically aligned with ISCI, Badr, and Dawa, the Sadrists have also had a contentious and violent relationship with several of these parties. Sadr fled to Iran in 2007 to avoid being targeted by U.S. and Iraqi forces, and to pursue his religious studies. He returned to Iraq in 2011 and continued to play an important role in Iraqi politics, though he has often distanced himself from Iranian policies.

Kurdish parties—the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)—have long-standing ties with Iran. Kurdish guerillas (Peshmerga) fought alongside Iran during the Iran-Iraq War. And Tehran armed the PUK during its fighting with the KDP from 1994 to 1998. Iran continues to enjoy close ties with the PUK and KDP, as well as Iraq’s northern Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). In the past, Tehran conducted occasional cross-border artillery strikes against Iranian Kurdish guerillas based in northern Iraq, though these activities have waned in recent years. Iran’s relationship with the Kurds has likewise improved as the KRG region became an important trading partner with Iran – a hub for busting international sanctions on the Islamic Republic.

Modes of influence

Iran exercises its influence through its embassy in Baghdad and consulates in Basra, Karbala, Irbil and Suleimaniyah. Both of its post-2003 ambassadors—Hassan Kazemi-Qomi and Hassan Danaifar, who was born in Iraq but whose family was expelled by Saddam Hussein—served in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) elite Qods Force. Their appointments reflect the role Iran’s security services play in formulating and executing policy in Iraq. The Qods Force is the IRGC unit in charge of Iran’s most sensitive covert foreign operations.

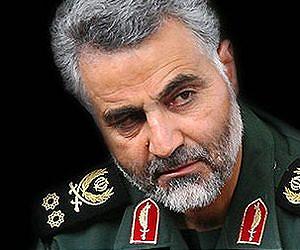

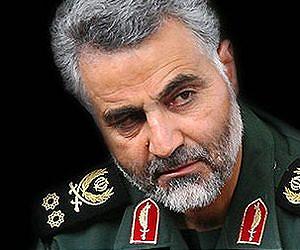

Iran reportedly tried to influence the outcome of the 2005 and 2010 parliamentary elections and 2009 provincial elections by funding and advising its preferred candidates. Qods Force commander Qassem Soleimani allegedly played a key role in negotiations to form an Iraqi government in 2005. He also reportedly brokered ceasefires between the Supreme Council and the Mahdi Army in 2007, and between the Iraqi government and the Mahdi Army in 2008. Iran unsuccessfully encouraged ISCI, Dawa and the Sadrists to run for the 2010 elections in a unified bloc. Following the 2010 election, Iranian Majles Speaker Ali Larijani reportedly prodded these parties to form a coalition government.

Iran played a less prominent role in the government formation process following the 2014 elections. Its preferred candidate for prime minister, Nuri al Maliki, was replaced by Haidar al Abadi at the urging of the United States and – more importantly – Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani. Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council Admiral Ali Shamkhani subsequently played a key role in the government formation process (standing in for Soleimani, whose continued support for a third term for Maliki made him unsuited for the task).

Iran has also vied for Iraqi “hearts and minds” through Arabic language news and entertainment broadcasts into Iraq (and the Arab world) over the al-Alam television network. The programs reflect Tehran’s propaganda line on news relating to the region. Al-Alam was launched on the eve of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Militias and insurgents

During the occupation, Iran encouraged its Iraqi political allies to work with the United States. But its Qods Force armed, trained and funded militias associated with these parties, as well as radical insurgent groups that attacked U.S. forces. These groups continue to provide Tehran the means to retaliate against the 3,500 U.S. advisors and trainers currently in Iraq, should the United States (or Israel) harm Iranian interests elsewhere in the region.

After 2003, Iran initially focused its resources on its traditional allies in ISCI’s Badr Corps. But it soon expanded its aid to include the Sadrists’ Mahdi Army, associated special groups and even some Sunni insurgent groups. It sometimes used Arabic-speaking Lebanese Hezbollah operatives to facilitate these efforts.

Iran’s support for the Mahdi Army proved particularly problematic. The Sadrist militia underwent a dramatic expansion after 2003, which led it to incorporate many criminal elements. The militia’s radical agenda and its competition for power within the Shiite community soon brought it into conflict with both the Supreme Council and the Iraqi government, thereby undermining Iranian efforts to unify the Shiite community.

Iran also reportedly facilitated the activities of the Ansar al Islam, a Salafi jihadist group in northern Iraq, which provided leverage over the Kurdish regional government and an entrée into Sunni jihadist circles.

By 2010, Iran had narrowed its support to three armed Shiite groups: Sadr’s Promised Day Brigade—the successor to the Mahdi Army—and two special groups: Asa’ib Ahl al Haqq (League of the Righteous) and Kata’ib Hezbollah (Battalions of Hezbollah). Iranian advisors reportedly returned to Iraq in mid-2010 with Kata’ib Hezbollah operatives trained in Iran to conduct attacks on U.S. forces as they drew down. Their goal was to create the impression that the United States was forced out of Iraq.

After the 2011 U.S. withdrawal from Iraq, many of these groups stood down. But when ISIS seized Mosul and began advancing on Baghdad, Grand Ayatollah Sistani issued a fatwa calling on Iraqis to rally behind Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) to defend their country, their people, and their holy places. Massive numbers of Shiites who volunteered were organized into various militias known as Popular Mobilization Units (also known as PMU or al Hashd al Shaabi).

The volunteers were organized into more than 50 new militias, numbering between 60,000-90,000 men. Many were armed by Iran and reflected a Khomeinist ideological orientation. These groups, along with Iran’s traditional allies such as Badr, Asa’ib Ahl al Haqq, and Kata’ib Hezbollah, played a lead role in the fight against ISIS. But they were sectarian actors who took a heavy handed military approach, and they were frequently involved in human rights abuses against Sunni Arabs. Thus they also contributed to the sectarian polarization of Iraqi society.

As of 2015, the long-term implications of the rise of the Popular Mobilization Units remained unclear. Much will depend on whether they are eventually integrated into the ISF or serve as a springboard for ambitious radical Shiite politicians seeking to translate their military achievements into political capital. They could also remain a parallel military force used by radical populist Shiite politicians to pressure the government - or by Iran to advance its interests in Iraq, in much the way that Hezbollah does in Lebanon.

Trade

Iran has pursued trade and economic ties with Iraq for financial gain, and to obtain leverage over its neighbor. Iran is reportedly Iraq’s largest trade partner. Iranian and Iraqi officials claimed that total trade between the two countries reached $12 billion in 2013 and 2014. But official Iranian statistics show that total trade was about $6 billion in that period, almost all of it consisting of Iranian exports to Iraq. The exports consist of fresh produce and processed foodstuffs, construction materials, inexpensive household appliances, and cars. Iranian investors and construction firms are also active in Baghdad, predominantly Shiite southern Iraq and Kurdistan.

Iranian dumping of cheap, subsidized food products and consumer goods into Iraq (as well as counterproductive Iraqi government policies) have undercut Iraq’s agricultural and light industrial sectors, generating resentment among Iraqis. Iran’s damming and diversion of rivers feeding the Shatt al Arab waterway has also undermined Iraqi agriculture in the south and hindered efforts to revive Iraq’s marshlands. And while Iran has made up for Iraq’s electricity shortages by providing about five to 10 percent of available supplies in Iraq (a proportion that is much higher for several provinces that border Iran), many Iraqis believe that Iran has at times manipulated these supplies for political ends.

Religious influence

Iran has been working to ensure the primacy of clerics trained in Qom, steeped in the Islamic Republic’s official ideology, over clerics trained in the relatively non-political “quietist” tradition of Najaf’s academies. Its goal is to ensure that its version of Islam is the dominant ideology among Shiites world-wide.

Iran may now be poised to achieve this goal, due to:

- Its lavish use of state funds for the activities of its politicized clerics.

- The 2010 death of Grand Ayatollah Hussein Fadlallah, an influential Lebanese cleric trained in Najaf.

- And the advanced age of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani—the foremost member of the Najaf school and marja, or source of emulation, for perhaps 80 percent of all Shiites. He was born in 1930 and is reportedly ailing.

Iraq has become a major destination for Iranian religious tourists. From 2013-2014, 1.2 million Iranian religious tourists visited holy sites in Najaf, Karbala, Kadhimiya and Sammarra. Likewise, during that period, 1.7 million Iraqis visited Iran. Iran invests tens of millions of dollars annually for construction and improvement of tourist facilities for its pilgrims.

Limits of influence

Despite significant investments to expand its influence in Iraq, Iran’s efforts have yielded only mixed results. The goal of Shiite unity in Iraq has proven elusive. Relations among its Iraqi clients have frequently been fraught with tensions and violence, and it has spent much time and effort mediating among them. Tehran’s meddling in Iraqi politics has sometimes been a liability, stoking a nationalist backlash against Iran and its local allies.

But the rise of ISIS and Iran’s quick response with arms, military support, and advisors after the fall of Mosul (compared to the comparatively slow and restrained U.S. response) has created opportunities for Iran to portray itself as Iraq’s savior. Its conduct since then has boosted its standing in the eyes of many Iraqis.

Yet Iran has occasionally overplayed its hand. Officials from Qassem Soleimani to presidential advisor and former intelligence minister Ali Younesi have boasted of Iran’s influence in Iraq, provoking a backlash among Iraqis. And its preferred military approach—the reliance on the PMUs—had not yielded decisive military results by late 2015, while contributing to the sectarian polarization of Iraqi society. U.S. reticence and restraint, however, are likely to ensure that Iran continues to play a major military role in Iraq – at least as long as ISIS remains an imminent threat, and Iraq proves unable to deal with that threat on its own.

Trendlines

- Geography, politics, economics and religion ensure that Iran will retain significant influence in Iraq. There will always be Iraqis willing to partner with Iran for pragmatic, ideological, or mercenary reasons, especially as long as Iran is seen as a rising power and the leader of the region’s most cohesive axis.

- The most powerful constraints on Iranian influence in Iraq remain Iraqi nationalism, Iran’s own policies, and it sometimes high-handed behavior. But without a determined U.S. effort to counterbalance the Iranian presence, Iran will remain the most influential outside power in Iraq.

- Over the long-term, Iraq’s relations with Iran will depend largely on its security situation (particularly the fate of ISIS), the political complexion of its government, and the type of long-term relationship it forges with the United States and its Arab neighbors.

Michael Eisenstadt is Kahn Fellow and Director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Photo credits: Abadi and Rouhani via President.ir; Qassem Soleimani by Aslan Media via Flickr Commons [CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]; Saddam Hussein via Wikimedia Commons; Ammar al Hakim by US Dept of State via Flickr Commons (cropped)

This chapter was originally published in 2010, and is updated as of August 2015.

Since ancient times, Iraq and Iran have been the seats of rival states and empires. Mesopotamia, today’s Iraq, was home to the Assyrian, Babylonian and medieval Abbasid empires. The Achaemenid, medieval Safavid and early-modern Qajar dynasties ruled in Persia.

Since ancient times, Iraq and Iran have been the seats of rival states and empires. Mesopotamia, today’s Iraq, was home to the Assyrian, Babylonian and medieval Abbasid empires. The Achaemenid, medieval Safavid and early-modern Qajar dynasties ruled in Persia. Since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iran has tried to influence Iraqi politics by working with Shiite and Kurdish parties to create a weak federal state dominated by Shiites and amenable to Iranian influence. Tehran has also supported Shiite insurgent groups and militias, and enhanced its soft power in the economic, religious and informational domains.

Since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iran has tried to influence Iraqi politics by working with Shiite and Kurdish parties to create a weak federal state dominated by Shiites and amenable to Iranian influence. Tehran has also supported Shiite insurgent groups and militias, and enhanced its soft power in the economic, religious and informational domains. Abadi, who spent his years in exile in the United Kingdom, represented a less insular tendency within the party. He continued Maliki’s policy of trying to hew a middle path between Washington and Tehran, while calling for reconciliation with Iraq’s Sunni Arab community. But the influence of sectarian elements within his State of Law Coalition and the ruling Iraqi National Alliance prevented him from implementing this agenda.

Abadi, who spent his years in exile in the United Kingdom, represented a less insular tendency within the party. He continued Maliki’s policy of trying to hew a middle path between Washington and Tehran, while calling for reconciliation with Iraq’s Sunni Arab community. But the influence of sectarian elements within his State of Law Coalition and the ruling Iraqi National Alliance prevented him from implementing this agenda. Iran reportedly tried to influence the outcome of the 2005 and 2010 parliamentary elections and 2009 provincial elections by funding and advising its preferred candidates. Qods Force commander Qassem Soleimani allegedly played a key role in negotiations to form an Iraqi government in 2005. He also reportedly brokered ceasefires between the Supreme Council and the Mahdi Army in 2007, and between the Iraqi government and the Mahdi Army in 2008. Iran unsuccessfully encouraged ISCI, Dawa and the Sadrists to run for the 2010 elections in a unified bloc. Following the 2010 election, Iranian Majles Speaker Ali Larijani reportedly prodded these parties to form a coalition government.

Iran reportedly tried to influence the outcome of the 2005 and 2010 parliamentary elections and 2009 provincial elections by funding and advising its preferred candidates. Qods Force commander Qassem Soleimani allegedly played a key role in negotiations to form an Iraqi government in 2005. He also reportedly brokered ceasefires between the Supreme Council and the Mahdi Army in 2007, and between the Iraqi government and the Mahdi Army in 2008. Iran unsuccessfully encouraged ISCI, Dawa and the Sadrists to run for the 2010 elections in a unified bloc. Following the 2010 election, Iranian Majles Speaker Ali Larijani reportedly prodded these parties to form a coalition government. After 2003, Iran initially focused its resources on its traditional allies in ISCI’s Badr Corps. But it soon expanded its aid to include the Sadrists’ Mahdi Army, associated special groups and even some Sunni insurgent groups. It sometimes used Arabic-speaking Lebanese Hezbollah operatives to facilitate these efforts.

After 2003, Iran initially focused its resources on its traditional allies in ISCI’s Badr Corps. But it soon expanded its aid to include the Sadrists’ Mahdi Army, associated special groups and even some Sunni insurgent groups. It sometimes used Arabic-speaking Lebanese Hezbollah operatives to facilitate these efforts.