Iran celebrates the anniversary of its 1979 revolution and the so-called “10 Days of Dawn” between February 1 and 11, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile. John Ghazvinian is the author of the new book “America and Iran: A History, 1720 to the Present.” Born in Iran, Ghazvinian is the Executive Director of the Middle East Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

Iran celebrates the anniversary of its 1979 revolution and the so-called “10 Days of Dawn” between February 1 and 11, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile. John Ghazvinian is the author of the new book “America and Iran: A History, 1720 to the Present.” Born in Iran, Ghazvinian is the Executive Director of the Middle East Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

Forty-two years after the revolution, what is the state of U.S.-Iran relations?

The state of U.S.-Iran relations is poor. It’s as bad as most of us can remember. The last four years, and especially the last year of the Trump administration, have been a low point for relations, if we could even call them relations.

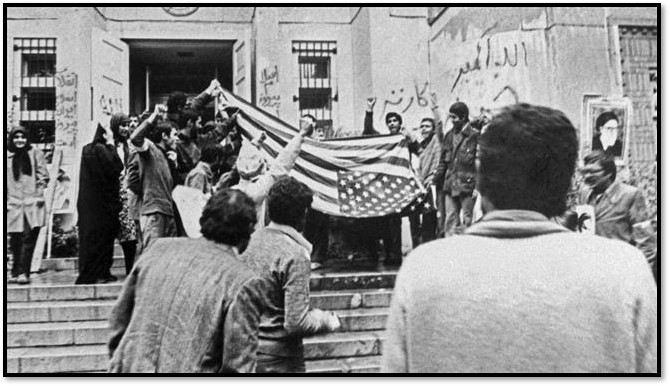

The 1979 to 1981 hostage crisis was a historic low point when relations were broken off and when 52 Americans were held hostage in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran for 444 days. But people forget that there have been other crises. The U.S. and Iran came to blows militarily during 1987 and 1988 during the so-called “Tanker War,” a series of tit-for-tat military exchanges and escalations during the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq.

But things are bad, and I can't put a particularly optimistic spin on it. It's hard to feel really hopeful, although we will see what happens with this new administration.

You track relations since 1720. When have the U.S. and Iran shared interests? And why?

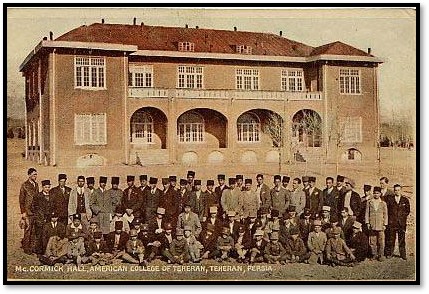

The biggest surprise for me has been to see how warm and affectionate the relationship between these two countries was for a long time. The last 42 years is a blip—and is not characteristic of the relationship for most of its history. Iran and the U.S. developed cultural affinity—and a mutual fascination—starting in the 1700s. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Americans admired the Persian Empire. They thought of Iran as a slightly more exotic eastern oriental kingdom that was less of a threat to them than the Arab world and the Ottoman Empire. In the late 19th century, Iranian reformers praised and admired the U.S. as a progressive, democratic, constitutional republic with economic strength.

Even before the U.S. attained independence, colonial American newspapers were fascinated by Iran and very pro-Iranian. Missionaries and travelers visited Iran before the two countries established political relations in the 1850s, and Iran’s first ambassador was sent to Washington in 1880s. Some of the earliest political relations were not particularly close or strategic, but they were warm and friendly.

From the 1850s until the 1940s, Iran prioritized developing a better relationship with the U.S.. But Washington did not reciprocate. Iran might as well have been in Antarctica as far as the State Department was concerned. The U.S. was not interested in far-flung places where there was no American interest.

The first disagreement between Iran and the U.S. was in the 1850s, when they were trying to sign the first treaty of friendship. Iran wanted the U.S. to be more involved. The government wanted American warships in the Persian Gulf. They wanted to fly the stars and stripes from Persian merchant ships in the Persian Gulf and American ships with American sailors in order to send a message to the British and Russians that they had a new friend. The U.S. said that it didn’t want to get involved.

Iranians liked the U.S. as an anti-imperialist power that had a revolution against the British Empire and had a long history of non-interference in the affairs of small and weak countries. In the early 20th century, Wilsonian rhetoric was taken very seriously in Iran. The U.S. had a very warm, positive reputation in Iran well into the 1940s and the early 1950s. Iranian newspapers, even the nationalist ones, criticized U.S. foreign policy with a tone of sadness: The Americans are new to the international scene. They’re probably getting misled by the British. They may not have enough experience. Favorable views of the U.S. persisted until the CIA-led 1953 coup that overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh's government and restored the shah.

One of the last letters that Mossadegh wrote as prime minister was to President Dwight Eisenhower — just three weeks before he was overthrown by the U.S. and Britain — to ask for help against the Britain embargo of Iranian oil and finances. Eisenhower said that he was not going to help. But right up until the coup, Mossadegh thought that the U.S. would naturally be inclined to understand his point of view. It was a tragic and ironic miscalculation.

After the 1953 coup, during the early years of the Cold War, the U.S. and Iran became increasingly close allies. Iran became of the one of Washington's most important regional allies, by the 1970s. It was almost a regional proxy. Iran was the largest purchaser of American military equipment in the early to mid-1970s. It bought billions of dollars in military equipment.

What interests—on diplomacy, security, the economy and energy—do they share today?

Today, Iran and the U.S. are looking for remarkably similar things in the wider Middle East. Both countries want to ensure freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf. They also have a shared interest in defeating ISIS and other extremists. Both countries fundamentally want a stable, peaceful Iraq. The same is true in Afghanistan. Iran hated the Taliban long before the U.S. hated the Taliban. There could be wide scope for cooperation in the region. Iran was helpful to the U.S. in Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks and could be again. The U.S., in turn, can marshal a level of raw power and money that Iran could never dream of. The problem is that Iran and the U.S. are often rivals in pursuit of the same goals.

Today, Iran and the U.S. are looking for remarkably similar things in the wider Middle East. Both countries want to ensure freedom of navigation in the Persian Gulf. They also have a shared interest in defeating ISIS and other extremists. Both countries fundamentally want a stable, peaceful Iraq. The same is true in Afghanistan. Iran hated the Taliban long before the U.S. hated the Taliban. There could be wide scope for cooperation in the region. Iran was helpful to the U.S. in Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks and could be again. The U.S., in turn, can marshal a level of raw power and money that Iran could never dream of. The problem is that Iran and the U.S. are often rivals in pursuit of the same goals.

On what are they most divided?

The division between the U.S. and Iran has become self-perpetuating. They are locked in a kind of a cold war, where national security interests are instrumentalized in the service of ideology. Iran's foreign policy is not that different, fundamentally, from its foreign policy under the shah — if you pull away its antagonistic relationship with the U.S. and the West, and by extension, Israel. Iran follows its basic national strategic security interests. So does the U.S. most of the time.

Iran has ideological as well as tactical reasons for supporting proxies like Hezbollah, a Lebanese political party and militia. Tehran sees Hezbollah's arsenal of missiles and rockets as insurance against an Israeli attack. Support for Hezbollah and the Palestinians buys Iran a lot of goodwill in Arab states.

What have been the top misperceptions between Washington and Tehran since 1979?

The greatest misconception in the U.S. is the idea that the Islamic Republic is a house of cards that is about to collapse. There is an assumption that the Iranian people, with enough incentives and support, will overthrow the government and install a pro-American one in its place. That’s an unhelpful way of looking at Iran because it simply is not true. That does not mean that the Islamic Republic is popular among Iranians. But you do not have to like the Islamic Republic to acknowledge that it's not a house of cards.

Iran’s system of government has survived for more than 40 years with few allies and in the face of opposition from at least one of the world's superpowers at any given time. The U.S. has tried to weaken and destabilize the Islamic Republic but has not succeeded.

Iranians understand the American political system a little better because it is more open and easier to understand. But Iran, like many countries, sometimes overestimates its own importance in the American mindset. Iran is not the top U.S. priority at any given time.

What are prospects for new diplomacy—or even renewed diplomatic relations?

There is no compelling reason why the U.S. and Iran must remain enemies. They could become friends and allies. But that's not going to happen tomorrow.

I do not anticipate any huge surprises in the coming months. The landscape is straightforward. Iran has a presidential election in June. President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif are heavily invested in trying to resurrect the 2015 nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). They want to prove that diplomacy with the U.S. can work and that the Trump administration was an exception. If they're not able to do that, then the reformist, moderate and pragmatic camps are headed for a massive election disappointment because the hardliners will argue that the U.S. is not trustworthy.

At the same time, the Biden administration has a lot of officials who negotiated the JCPOA and are also invested in its success. The U.S. and Iranian teams know the issues very well and, in many cases, have worked together personally. But there is a very tight window for diplomacy. And the Biden administration has many other pressing issues on its plate, both domestic and foreign.

But the U.S. and Iran can also improve their relations without fixating on the JCPOA. The nuclear deal was always meant to be a starting point of a conversation, and it could have been if the Trump administration had not withdrawn from it. If the U.S. provided some sanctions relief, recognition and respect, and Iran, in turn, demonstrated some of its bona fides, perhaps there could be a gradual detente. And the nuclear issue could be part of that.

How do Iran’s political factions—and the divide among them—influence dealing with the U.S.?

Sometimes the divisions between Iran’s political factions are overstated. Some of these labels – reformists, moderates, pragmatists and hardliners – are slippery. Iran has never had a strong party system, so it's hard to really know who stands for what. But there are issues that all political actors in the Islamic Republic agree on. For example, all factions are committed to Iran’s right to a peaceful nuclear program, including uranium enrichment. There is no daylight between any members of the political establishment on this or even among most of the Iranian public. All government factions are also committed to the survival of the Islamic Republic.

Is there a constituency with a vested interest in an adversarial relationship with the U.S.?

Yes, there is a grassroots anti-American constituency in Iran. The hardliners are ascendant right now in large part because of the Trump administration’s policies. The U.S. made it very easy for Iran to adopt this very anti-American posture because it served Iran well. The U.S. shot itself in the foot. The easiest way to embolden reformist, moderate and pragmatist forces in Iran is to behave differently than the Trump administration.

But politics can shift in Iran. The anti-American bloc was not ascendant in 1997, when reformist Mohammad Khatami was elected president. It was not ascendant in 2015, when the nuclear deal was brokered by President Rouhani’s administration. Also, we have to separate rhetoric from reality. People can be convinced to see that their interests can change.