What are the Houthis' political views and goals?

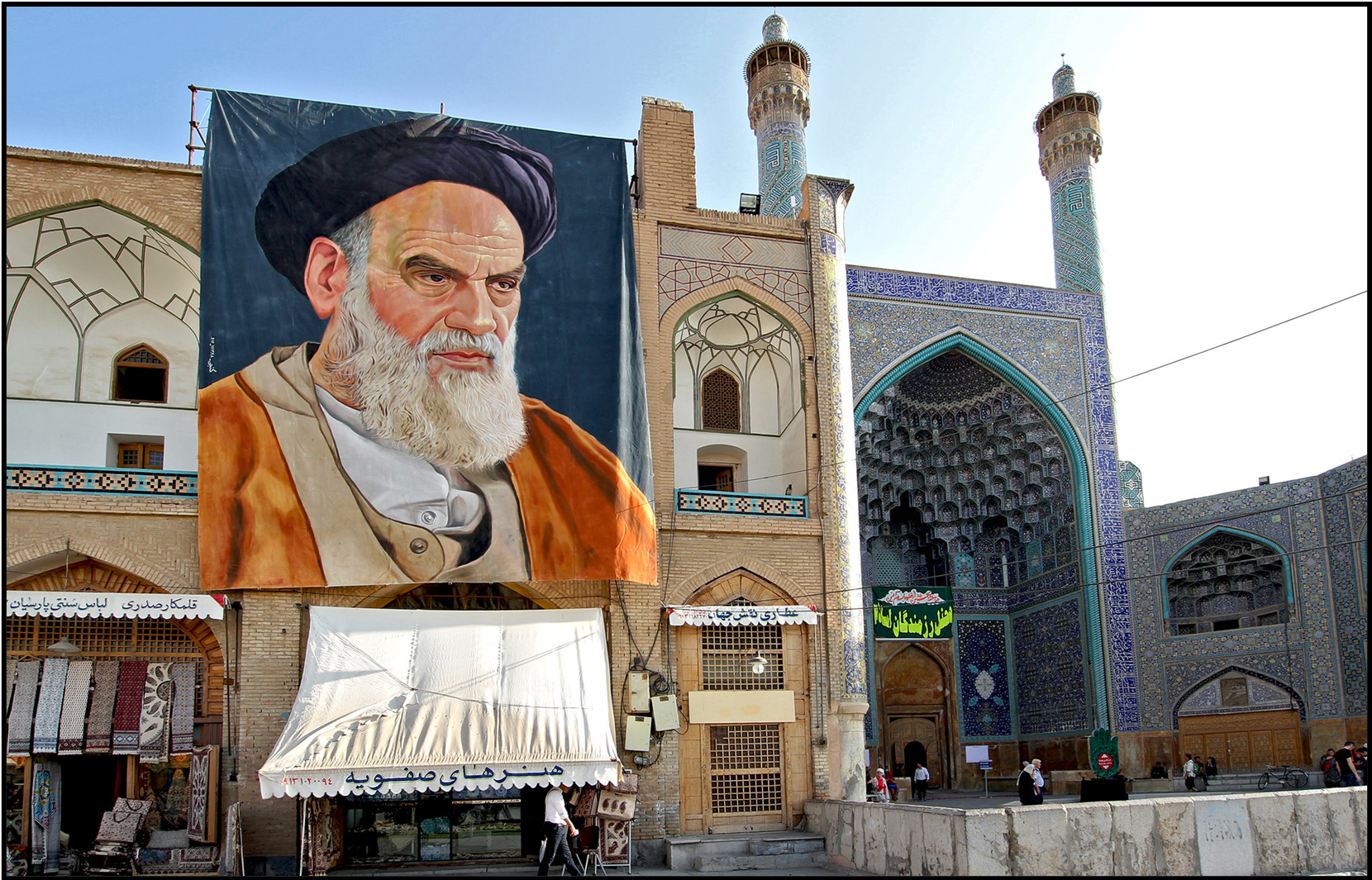

Since the 2000s, Houthi leaders have issued vague or contradictory statements about Yemen's political future as their religious movement evolved into an insurgency – and, as of 2015, the dominant political and military force in Sanna after ousting the Saudi-backed government. The Houthis to revive Zaydi Shiism and prevent Wahhabism, an ultraconservative form of Sunni Islam from Saudi Arabia, from marginalizing them. Houthi ideology has been a mix of Zaydi revivalism, anti-imperialism, and Yemeni nationalism, Fatima Abo Alasarar, a scholar at the Middle East Institute, told The Iran Primer. It has also borrowed elements from the radical Shiite activism proposed by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the late revolutionary leader of Iran. The Houthi slogan – “God is great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Damnation to the Jews, Victory to Islam” – has broadly reflected its ideology.

The Houthis have recruited followers by branding themselves as defenders of Yemeni sovereignty against intervention by the United States, Saudi Arabia and their allies. “The people of the region should realize that their security and stability are subject to proceeding with the liberating project until the expulsion of the American occupier,” Houthi leader Abdel Malek al Houthi said in January 2020.

Rather than framing themselves as a strictly Zaydi religious movement, the Houthis have used nationalist and populist language in their messaging. They long contended that the internationally recognized Yemeni government was corrupt and beholden to the United States and Saudi Arabia. Despite their alliance with Shiite Iran, this strategy helped them to cultivate Sunni supporters. Yet the Houthis did not articulate a coherent political vision even after they took control of Sanaa, Yemen’s capital, in 2014, and ousted the government in 2015. At times, officials expressed support for a united and democratic Yemen.

The Houthis’ inclusive rhetoric often sharply contrasted with the highly centralized and authoritarian model of governance in their territory, home to some 80 percent of Yemen’s population of 35 million as of 2024. The Houthis “assert control over political, economic, and social life within their territories, suppressing dissent and limiting freedoms in the name of security and stability,” said Fatima Abo Alasarar. Professor Thomas Juneau of the University of Ottawa told The Iran Primer that there was no space for political dissent in Houthi-controlled territory. “Independent civil society and media are systematically crushed,” he added. “The Houthis are also transforming school curricula to ensure that they reflect their idiosyncratic world view.”

For years, human rights groups have documented arbitrary detentions, torture of prisoners, hostage taking and enforced disappearances by Houthi authorities. In May-June 2024, Human Rights Watch documented the enforced disappearance of dozens of people, including U.N. staff members and employees of nongovernment organizations, by the Houthis. The Houthis have also persecuted religious minorities, including Christians, Baha’is and Jews.

Houthi critics alleged that Houthis’ goal was to establish a Zaydi theocracy in Yemen led by Abdel Malek al Houthi. The Houthi family “regards themselves and a narrow group within Zaydi Shiism as being the rightful rulers of the Yemeni state,” Alexandra Stark, a policy researcher at RAND Corporation, explained. When asked if the Houthis would share political power with other factions, a Houthi spokesperson told The Atlantic in early 2024 that Abdel Malek al Houthi will retain absolute power in any future government.

Beyond Yemen’s borders, the Houthis have expressed ambitions for strengthening ties with countries opposed to the U.S.-led world order. “We have the right to establish relations with Russia, China, Iran, the BRICS countries, Cuba, and [North] Korea,” Abdulsalam Jahhaf, a member of the Houthi Shura Council, wrote on X (formerly Twitter) in March 2024. “Everyone hostile to America is our friend. We will widely accept alliances and exchange of military expertise and information. This is a natural result of the West's aggression against us and against our people in Gaza, under the leadership of America.”

The Houthis welcomed direct conflict with U.S. forces in the Red Sea in 2024. Ali al Qahoum, a member of the Houthi political bureau, said that the Houthis wanted to drown the United States, Britain and the West in the Red Sea. “[Our] goal is to make it [the U.S.] sink and disappear, and weaken its unipolarity,” he declared in March 2024.

Where are the Houthis' strongholds? What role have they played in Yemen's history?

The Houthis are a large clan originating from Yemen’s northwestern Saada province. They practice the Zaydi form of Shiism. Zaydis make up around 35 percent of Yemen’s population and Sunnis account for some 65 percent. A Zaydi imamate ruled Yemen for a millennium before being overthrown in 1962 by army officers who declared a republic. Since then, the Zaydis – stripped of their political power – have struggled to restore their authority and influence.

In the 1990s, the Houthi clan began a movement to revive Zaydi traditions, feeling threatened by rising Saudi influence. Not all Zaydis, however, aligned with the Houthi movement. Houthi insurgents clashed with Yemen’s government in six wars between 2004 and 2010. The group expanded beyond its Zaydi roots and became a wider movement opposed to President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi – a Sunni from southern Yemen aligned with Saudi Arabia – who took office in 2012 after the Arab uprisings. The Houthis took over the capital, Sanaa, in September 2014 and seized control over much of north Yemen by 2016.

What is the relationship between the Houthis and other Islamists in Yemen?

The Houthis have had a tense relationship with Islah, a Sunni Islamist party with links to the Muslim Brotherhood. Islah has claimed that the Houthis are an Iranian proxy, and blames them for sparking unrest in Yemen. The Houthis, on the other hand, have accused Islah of cooperating with al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

After the Houthis took over Sanaa in September 2014, Islah initially took a few steps towards reconciliation. In November, top Islah and Houthi leaders met to discuss a political partnership. Islah called on the Houthis to cease attacks on Islah members and to release Islah prisoners. In December 2014, the United Nations and Gulf Cooperation Council brokered a deal between the two groups to cease hostilities.

But clashes between the Houthis and Islah continued. In the first four months of 2015, the Houthis kidnapped dozens of Islah party leaders and raided their offices. By April, more than 100 Islah leaders were detained by the Houthis. Tensions increased after Islah declared support for the Saudi-led airstrikes. Some Islah leaders chose exile in Saudi Arabia rather than live under Houthi rule.

The Houthis have had both antagonistic and working relations with Sunni extremist groups. On March 20, 2015, an ISIS affiliate calling itself the Sanaa Province claimed responsibility for suicide bomb attacks on two Zaydi mosques that killed at least 135 people and injured more than 300 others. The group issued a statement that said “infidel Houthis should know that the soldiers of the Islamic State will not rest until they eradicate them.”

AQAP denied involvement in the mosque attacks but has targeted the Houthis. In April 2015, the group claimed responsibility for three suicide attacks that killed dozens of Houthis in Abyan, al Bayda’, and Lahij. AQAP has reportedly partnered with southern tribes to fight the Houthis.

In subsequent years, however, the Houthis have reportedly cooperated with AQAP and ISIS. “The Houthis have provided tactical help, cooperation, prisoner exchanges and handover of military camps to [ISIS] under Houthi supervision,” according to a 2020 U.N. report. In 2023, the Houthis acknowledged prisoner exchanges with AQAP. By 2024, the Houthis had reportedly provided drones to AQAP and were coordinating deployments to attack Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist organization and a mutual adversary, in a bid to take control of southern Yemen.

How does Zaydism compare to the type of Shiism practiced in Iran?

Zaydis are a minority within a minority in Islam. Only 10 to 15 percent of the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims are Shiite while the rest are Sunni. Most adherents of Zaydism reside in Yemen, and Zaydis make up around eight percent of the world’s 70 million Shiites.

Like other Shiites, Zaydis believe that only descendants of the Prophet Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali, have the right to lead the Muslim community as imams - divinely-appointed successors of the Prophet. In Yemen, descendants of Prophet Muhammad, sadah, hold a privileged position in society. The Houthi clan hails from that class.

But the Zaydis are distinct from the “Twelver” form of Shiism practiced by the majority of the world’s Shiites, including most Shiites in Iran. Twelver Shiites believe the twelfth imam, whom they consider infallible, disappeared in 941 CE and will one day return to usher in an age of justice as the Mahdi, or promised one. In the Mahdi’s absence, Twelver Shiites believe clerics can substitute for his authority on certain issues. The faithful are supposed to follow the clerics’ religious rulings, a power transferred to Iran’s theocracy after the 1979 revolution.

Zaydis, also known as “Fivers,” believe that Zayd, the great-grandson of Ali, was the rightful fifth imam. But Twelver Shiites consider Zayd’s brother, Muhammad al Baqir, the fifth imam. The Zaydis do not recognize the later Twelver imams. They believe that only relatives of Ali and his wife Fatima can be imams. Historically, Zaydis rejected the Twelver doctrine that the imam is infallible. But Houthi leaders reportedly believe that they are chosen by God and therefore vested with absolute authority.

The Houthis, unlike some of Iran’s Shiite allies, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, do not explicitly recognize Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as their marja' (source of emulation) or highest religious authority. But the movement’s leaders belong to the Jarudi denomination, the Zaydi sect closest to Twelver Shiism. As a result, the Houthi clan has had strong connections to Iran for decades.

The family of Badr al Din al Houthi, a prominent religious scholar and the father of the Houthi’s leader, celebrated the success of Iran’s 1979 revolution and transformation into an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Khomeini. Badr al Din al Houthi traveled to Iran for religious studies in the holy city of Qom in the 1990s. Iran has reportedly paid for hundreds of Houthi religious students to study in Qom since 1994.

At least three of Badr al Din’s 13 sons accompanied him on trips to Iran, including Hussein, who founded the Houthi movement and led it until he died fighting Yemeni government forces in 2004, and Abdul Malek, who succeeded Hussein. Badr al Din and his family also reportedly traveled to Beirut, where they took inspiration from Hezbollah, a powerful Shiite political movement and militia.

Hussein espoused increasingly radical views following repeated trips to Iran and a year of study in Sudan, then a close partner of Iran, from 1999 to 2000. After his return to Yemen in 2000, he introduced what became the Houthi slogan: “God is great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Damnation to the Jews, Victory to Islam.”

Iranian influence has been reflected in the adoption of some Twelver Shiite practices by Yemenis. For example, Houthi supporters reportedly observed Ashura in public for the first time in 2017. The solemn day commemorates the anniversary of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, during the Battle of Karbala in 680 C.E. The Houthis have also encouraged the celebration of Eid al Ghadir, which commemorates Muhammad’s designation of his son-in-law Ali as his successor.

Who are the leaders of the Houthi movement?

Abdel Malek al Houthi

Abdel Malek al Houthi has led the movement since 2006. Born in Saada in northwestern Yemen between 1979 and 1982, he hailed from a prominent Zaydi Shiite family believed to be descended from the Prophet Muhammad. His father, Badr al Din al Houthi, was a cleric and scholar who gave his son a religious education and took him on visits to Iran and Lebanon.

Abdel Malek al Houthi moved to Sanaa in the mid-1990s to live with his older brother, Hussein al Houthi, who served as a role model. Hussein al Houthi had established the “Believing Youth Movement,” a precursor to the Houthis. Hussein al Houthi founded Ansar Allah (Supporters of God), also known as the Houthi movement, in 2004 and was killed in the first insurgency against Yemen’s central government that same year.

Abdel Malek al Houthi led Houthi forces in all six wars against the central government from 2004 to 2010. He developed a reputation as a competent battlefield commander before becoming the group’s spiritual, military, and political leader in 2006.

Abdel Malek al Houthi rose to prominence after the 2011 Arab uprisings, as the group seized control of provinces in northwestern Yemen. In 2015, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned him for engaging in acts that “threaten the peace, security, or stability of Yemen.” The U.N. Security Council also blacklisted him.

Due to security concerns, the Houthi leader rarely appeared in public and frequently relocated. But he did give fiery speeches on television in which he often condemned the United States, Israel and Saudi Arabia. The United States “plays a major role in the (Saudi) aggression... including logistical support for air and naval strikes, providing various weapons... and providing complete political cover,” he said in September 2016.

Abdel Malek al Houthi often pledged that the Yemeni people did not just support the Palestinian cause but were ready to fight Israel. “The Zionist enemy is an eternal enemy for the Arab and Muslim nations,” he said in April 2024 after Israel struck an Iranian facility in Damascus, Syria, and killed senior military officers.

Yusuf al Madani

Major General Yusuf al Madani has served as the commander of the Houthis’ Fifth Military Region for years. He was born in Muhatta in northwestern Yemen in 1977. He studied under Houthi clerics in Saada, where he became familiar with Hussein al Houthi’s “Believing Youth Movement.” He joined the movement and later married Hussein al Houthi’s daughter.

Al Madani reportedly traveled to Iran to train with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in 2002 and returned to Yemen in 2003. He has served as a prominent Houthi military commander since 2004 and has reportedly operated as an important conduit between the Houthis and Iran. He served as a commander in all six war against Yemen’s central government from 2004 to 2010 and played a major role in the Houthi takeover of Sanaa in 2014.

In 2021, the United States and United Nations each designated al Madani a terrorist and sanctioned him. At the time, al Madani commanded Houthi forces in the Yemeni cities of Hodeida, Hajjah, al Mawhit, and Rayma.

Like other Houthi leaders, Madani has expressed solidarity with the Palestinians. “Any escalation in Gaza is an escalation in the Red Sea,” al Madani warned in December 2023. “Any country or party that comes between us and Palestine, we will confront it.”

Muhammad Abdel Karim al Ghamari

Muhammad Abdel Karim al Ghamari has served as the Head of the General Staff of the Houthi Forces since 2016. He was born in Wahha in northwestern Yemen, reportedly in either 1979 or 1984. He studied at the Hussein al Houthi Institute in 2003, which helped him to climb the ranks.

Al Ghamari received military training in Houthi camps run by Iran’s IRGC and by Lebanese Hezbollah. He reportedly traveled to Syria and Lebanon for training as well. In 2009, al Ghamari visited Tehran, where he learned to use artillery and rocket shells. He served as a commander in all six wars against Yemen’s central government from 2004 to 2010 and played a role in the takeover of Sanaa in 2014.

In Yemen, al Ghamari established Houthi military training camps and procured weapons. He was appointed chief of staff of the Houthi military in 2016 and promoted to the rank of major general. He orchestrated attacks against the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia as well as the internationally recognized government of Yemen.

In 2021, al Ghamari led the Houthi offensive against the Yemeni Armed Forces in Marib. He allegedly planned attacks on infrastructure that harmed civilians. The U.S. Treasury and the U.N. Security Council imposed sanctions on him for threatening the “peace, security, or stability of Yemen.”

Other Houthi leaders

- Muhammad Ali al Houthi, head of the Houthi supreme revolutionary committee

- Abdullah Yahya al Hakim, Chief of Military Intelligence sometimes described as the movement’s second-in-command

- Muhammad al Atifi, the so-called "Minister of Defense"

- Muhammad Fadl Abd al Nabi, commander of Houthi maritime forces

- Muhammad Ali al Qadiri, Coastal Defense Forces Chief and Director of the Houthi Naval College

- Muhammad Ahmad al Talibi, director of weapons procurement

Related Material:

- Houthi Explainer: Ties to Iran

- Houthi Explainer: Conflict in the Red Sea

- Houthi Explainer: Military Arsenal

- Houthi Explainer: Timeline of Attacks

- Houthi Explainer: Conflict with Israel

- Houthi Explainer: U.S. Sanctions