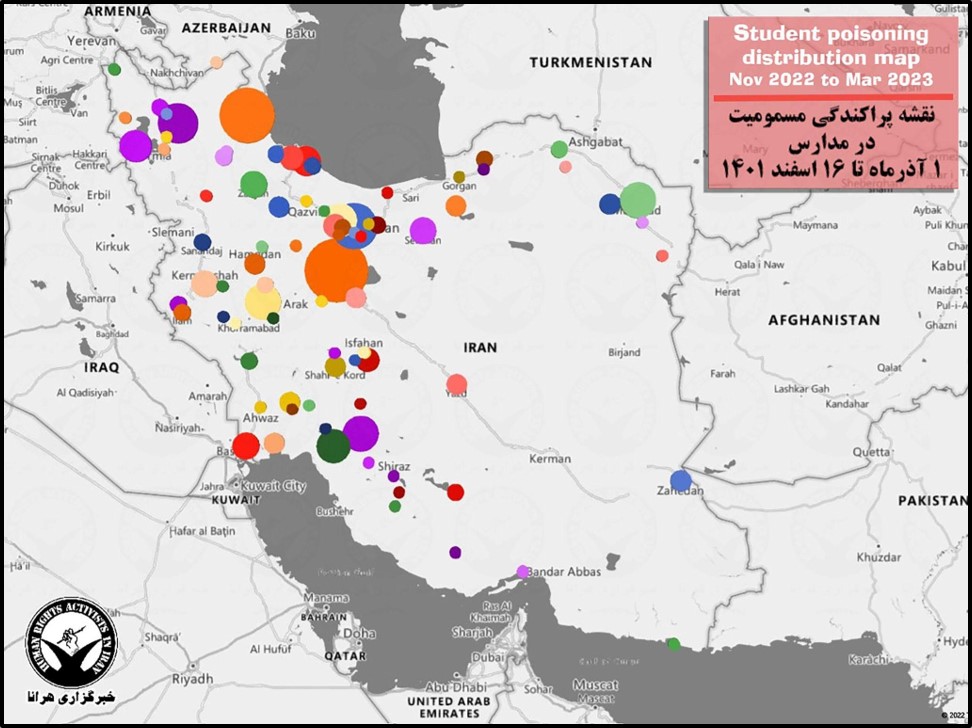

Between November 2022 and March 2023, up to 7,000 schoolgirls were poisoned at dozens of schools in at least 28 of Iran’s 31 provinces, according to human rights groups and government officials. Hundreds were hospitalized with symptoms that included respiratory distress, numbness in limbs, heart palpitations, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. The outbreak at schools for girls, first reported in the holy city of Qom, generated new protests against the government.

The government initially dismissed the illnesses as “rumors” and blamed the “underlying diseases” and “anxiety” of the students, even though the girls reported distinctive smells, such as citrus fruit or chlorides. On February 28, the Health Ministry said a team of 30 toxicologists identified the toxins that poisoned the girls as nitrogen gas, which is invisible, tasteless and odorless.

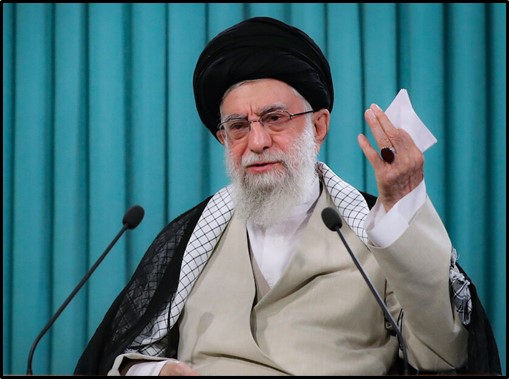

As the frequency of incidents escalated, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei described the wave of poisonings as “a huge, unforgivable crime.” On March 6, he demanded that the perpetrators, when caught, face the death penalty. The new crisis followed nationwide protests over personal freedoms, soaring inflation as the value of the rial has dropped another 30 percent in just two months, and fuel shortages during a bitter winter.

On March 7, Interior Minister Majid Mirahmadi announced that the government had arrested five people connected to the poisonings. Gen. Saeed Montazer al Mahdi charged the perpetrators, who were working for foreign adversaries, sought to “create insecurity and chaos.”

New anti-government protests over the poisonings erupted in mid-February. By early March, demonstrations were organized around Ministry of Education offices in Tehran and other provincial capitals, including Mashhad, Rasht, Sanandaj, and Shiraz. In the Iranian capital, angry families shouted slogans comparing the Revolutionary Guards and other law enforcement agencies to ISIS, the Sunni extremist movement. On March 6, protestors in Tehran chanted, “Death to the child-murdering government.”

Iran also faced mounting global condemnation for its delayed response. A spokesperson for the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva called for a transparent investigation. The White House demanded “a credible independent investigation” and “accountability for those responsible.” On March 6, White House spokeswoman Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters, “If these poisonings are related to participation in protests then it is well within the mandate of the U.N. independent international fact finding mission on Iran to investigate.”

Human rights groups blasted the Iranian government for being unable or unwilling to stop the attacks against Iranian schoolgirls and allow them to continue their schooling. “International support is urgently needed to protect Iranian children and their right to education,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran.

During the Islamic Republic’s first four decades, Iran made major strides in educating females. Before the revolution, literacy among females was 28 percent. Female literacy among girls 15 to 24 soared to 99 percent by 2021, according to the World Bank. Iran won the U.N. award for closing the gender gap in education in 1998. For years, the university student body was over 60 percent female.

Over the years, young women have become crucial players in Iranian politics and society. Starting in September 2022, young women in their teens and twenties were the driving force behind protests demanding an end to hijab, or the strict dress code. “School girls enthusiastically joined the anti-state protests in Iran,” Ghaemi said. “Like the Iranian government, the people who are carrying out these attacks are petrified of these girls’ potential and power.”

Senior Iranian officials charged that the perpetrators of the attacks sought to block girls from attending schools, where many of the protests originated. “Poisoning female students intentionally is very bad news,” Alireza Monadi, the head of parliament’s education committee, told Iranian media. “The fact that a group of people wanted to prohibit young girls from attending school is alarming. We have to find the roots of it.” The following is a timeline of events related to the poisonings.

2022

Late November: Hundreds of students reported suffering from symptoms that included vomiting, diarrhea, and body aches at four colleges in Tehran, Isfahan, Arak and Karaj. Officials in Isfahan initially cited bacteria in the food as a possible cause.

Nov. 30: In Qom, 18 students at the Noor Yazdanshahr Conservatory for girls reported poisoning by inhalation.

Dec. 13: The Noor Yazdanshahr Conservatory reported that 51 students were sick from poisoning.

2023

Feb. 14: In Qom, 117 girls became sick. Parents protested and demanded answers at protests outside government offices. Cases were also reported at the Doshifete middle school for boys in Qom.

Feb. 22: At a press conference, Minister of Education Yusef Nouri blamed the illnesses on “rumors” and “underlying conditions.”

Feb. 26: Younes Panahi, the deputy health minister, said that the poisonings were intentional and aimed at closing schools for girls. “It became clear that some people wanted all schools, especially girls’ schools, to be shut down,” he said. But Panahi later charged that he was misquoted.

Feb. 26: Fatemeh Rezaei, an 11-year-old girl in Qom, became the first known death linked to the poisonings.

Feb. 28: Health Minister Bahram Einollahi told Tasnim News that a “mild poison” caused the recent illnesses.

Feb. 28: Some 37 reported being poisoned at the Khayyam High School in Pardis, near Tehran. Nearly 200 girls reported being poisoned at four schools in western Borujerd over the previous week.

March 1: More than 100 girls were hospitalized in northwestern Ardabil with poisoning. President Raisi instructed his minister of interior to lead an investigation into the illnesses. Amnesty International said the “attacks on school girls in Iran must be stopped.”

March 3: Local and international media estimated that the total number of victims had risen to between 800 and 1,200 at 58 schools in eight provinces. The United States and Germany as well as officials at U.N. Human Rights Council demanded transparent investigations into the mass illnesses.

March 4: Parents launched anti-government protests outside the Ministry of Education in Tehran. “In field studies, suspicious samples have been found, which are being assessed,” Interior Minister Ahmad Vahidi told local media.

March 5: Dozens of girls were hospitalized as poisoning were reported at some 80 schools, according to Iran International, a Persian language TV station. Security forces detained Ali Pourtabatabaei, a journalist in Qom who was covering the poisonings.

March 6: In a speech, Supreme Leader Khamenei called the poisonings an “unforgivable crime” for which perpetrators should be severely punished.

President Raisi created a task force--to include security and law enforcement agencies as well as the health Ministry and laboratories--to investigate.

Interior Minister Vahidi claimed lab tests showed that none of the students had been exposed to “toxic and dangerous” materials, while “stimulants” that do not cause “lasting risks” had been found in less than five percent of the cases. “More than 90 percent of the students expressed their discomfort due to the anxiety and worries created in the classroom,” he said.

Foreign media reported that students hospitalized in Ardabil and Tehran were warned by security forces to remain silent about the poisonings. Parents were also reportedly blocked from visiting children in hospitals.

March 7: The government reported the arrest of five people connected to the poisonings. One of the detainees had sent a video to “hostile media” to create public “fear and apprehension.” Another official claimed that some of the detainees were students engaged in pranks. The Tehran prosecutor announced formal charges against journalists and activists.

Protesters, including parents and teachers, condemned the government in more than a dozen cities, including Tehran, Shiraz, Mashhad, Rasht, and Sanandaj. Some chanted, “Death to the child-killing regime.”

In a report on the situation for women in Iran, HRANA, a human rights monitoring group, claimed that some 7,000 students at more than 103 schools spread across 28 provinces had taken ill.

March 8: The judiciary announced that three people were detained for “spreading rumors” about the poisonings. The Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) said that it had discovered the causes of “some previous incidents” of “students’ distress.” But the ministry said that it could not generalize for all cases. Reporters Without Borders, a rights group, called for the release of Ali Pourtabatabaei, a journalist who covered the outbreak of poisonings in Qom. He had been detained on March 5. The U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) called for “thorough investigations” and “immediate actions to protect schools” so students could return safely to classrooms.

.@UNESCO urges thorough investigations and immediate actions to protect schools and facilitate the return of affected students in Iran, to their safe and healthy classrooms.#CSW67 #IWD2023 pic.twitter.com/PsG1p5hE4l

— UNESCO 🏛️ #Education #Sciences #Culture 🇺🇳 (@UNESCO) March 8, 2023

March 9: Some 300 university professors warned the government against “covering up the crime” of the “disaster of chain and organized chemical attacks” on schools for girls. In a statement, they said that “covering up this crime… and not exposing and prosecuting the perpetrators” would be seen as “complicity and alignment,” which would have “stormy consequences.” The statement was backed by professors from multiple universities, including in Tehran, Isfahan, and Shiraz. They called on the government to be transparent and solve the problem.

March 10: Iran TV aired the confessions of a father and a student who allegedly attacked schools with gas. Security forces reportedly detained a blogger in Urmia, West Azerbaijan province. Friday prayer preachers condemned the attacks. In Tehran, Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami called on the judiciary to “deal decisively with those who spread rumors” about the poisonings. He blamed the leaders of nationwide “riots” for wanting to “create discord” by poisoning children. In Kerman, Hojatoleslam Hassan Alidadi Soleimani said that the perpetrators should be “arrested and severely punished.” He warned that the “enemy wants to enter a new phase of… war, which does not even spare children.”

The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution claimed that the majority of the poisonings were “caused by emotional behavior and the stress of dear students and girls caused by mental pressure.” It also said that the Islamic Republic would “not allow any kind of abuse and violation of its citizens,” and that any perpetrators “will be punished for their actions without any tolerance.” It added that the “internal and external factors disrupting the country’s security” would be exposed.

March 11: More than 100 people “responsible for the recent school incidents” had been detained across 11 provinces, the Interior Ministry said. Some of the detainees had “hostile motives” and sought to instill terror in people. “Initial inquiries show that a number of these people, out of mischief or adventurism and with the aim of shutting down classrooms and influenced by the created psychological atmosphere, have taken measures such as using harmless and smelly substances,” the ministry added. The ministry was also investigating a “possible connection” with Mujahedeen-e Khalq (MEK), an exiled opposition group.

The government claimed that the rate of poisonings was decreasing. But dozens of students in at least ten schools were reportedly poisoned, including in Khuzestan, Fars, Kurdistan, and Gilan provinces, on March 11. “Less than 10 percent” of cases involved “an irritant gas” that was not “weapons-grade or deadly,” reported the Human Rights Headquarters of the Islamic Republic of Iran, an affiliate of the judiciary. It claimed that the majority of cases were stress-related.

March 12: Education Minister Nouri blamed the media for inducing panic among students. A member of Parliament claimed that “all the behind the scenes agents” had been detained. People who were “intentionally involved” in the poisonings would be “severely punished,” Mohammadreza Mirtaj al Dini said. Some 30 students at Allameh University in Tehran were banned from entering campus for protesting the poisonings, a student activist account reported on Telegram.

March 13: Schoolgirls were reportedly poisoned in Baneh, Kurdistan province, and Mahshahr, Khuzestan province. Some 13,000 schoolgirls had been treated for symptoms linked to the poisonings as of March 12, according to Deputy Health Minister Saeed Karimi. Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei, the judiciary chief, called for judges to “seriously, speedily, accurately, and fairly deal” with the cases of detained suspects.

March 14: In Birjand, South Khorasan province, 13 schoolgirls were reportedly poisoned at a primary school. A provincial education official claimed that the students had not been poisoned. “Only the anxiety and stress in the students caused the families to worry,” Seyyed Alireza Mousavinejad said.

March 15: The police said that 110 people had been detained for involvement in the poisonings. The police had also reportedly seized thousands of stink bomb toys. A 4,000-member patrol had been created to monitor and protect schools, said Gen. Saeed Montazer al Mahdi, a police spokesperson. It was unclear if the round of arrests was separate from the Interior Ministry's previous announcement that more than 100 people had been detained.

March 16: Eight U.N. officials, including three special rapporteurs, condemned the poisonings. “We are deeply concerned about the physical and mental well-being of these schoolgirls; their parents and the ability of the girls to enjoy their fundamental right to education,” they said in a statement. “While arrests have just been announced, we remain gravely disturbed by the fact that for several months, State authorities not only failed to swiftly investigate the attacks, but repeatedly denied them until recently.” They added that the government’s response was “further evidence of a pattern by Iran authorities to silence all who try to report on or demand accountability for human rights violations.”

The European Parliament called for the United Nations to investigate the poisonings. “The resolution condemns the regime's months-long failure to act on, as well as its deliberate suppression of, credible reports of systematic toxic attacks against schoolgirls,” the 27 countries said.

April 4: Twenty schoolgirls were reportedly poisoned in Tabriz. The girls were hospitalized with symptoms including shortness of breath. “Emergency experts were immediately dispatched to the scene after a report that a number of students from one of the girls’ high schools in Tabriz were in a bad condition,” the head of Tabriz’s emergency services said.