The most complicated issue in U.S.-Iran diplomacy is the overlapping network of U.S. sanctions that punish the Islamic Republic on multiple counts, from activities related to the nuclear program and support of terrorism to missile proliferation and human rights abuses. Some of Iran’s major institutions, including the Central Bank and the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), are sanctioned both for their roles supporting the nuclear program and for aiding terrorist attacks by proxy militias.

The Biden administration has vowed to lift the sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear program – as promised in the 2015 deal – if Tehran, in turn, rolls back recent breaches of the nuclear deal. The complicating factor in current and future diplomacy is that key Iranian institutions and individuals could remain sanctioned for secondary reasons, thus not providing Iran the economic relief it seeks.

Iran’s oil industry, the country’s main source of export revenue, is a prime example. Biden could lift sanctions on NIOC for its role in funding programs on weapons of mass destruction. But it would remain sanctioned for financially facilitating terrorism orchestrated by the Revolutionary Guards. The same problem of overlapping sanctions could arise in any future talks about Iran’s missile program because institutions involved in proliferation are also sanctioned for supporting regional terrorism.

The Biden administration has the authority to provide temporary exemption from sanctions; it would keep sanctions in place legally but nullify their effects until the Treasury formally revokes sanctions. “Iran is unlikely to be satisfied with such an approach and could demand formal removal of counterterrorism sanctions on these entities, a move that would be hugely unpopular in U.S. domestic circles,” Brian O'Toole wrote for the Atlantic Council.

The issue of sanctions was complicated when President Donald Trump abandoned the nuclear deal—brokered by the world’s six major powers over two years of intense diplomacy—in 2018. He then reimposed earlier sanctions from the Bush and Obama administrations that had been lifted when the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was implemented in 2016. He also took the unusual step of sanctioning Iran’s banking and oil sectors for funding the Revolutionary Guards and extremist proxies across the Middle East.

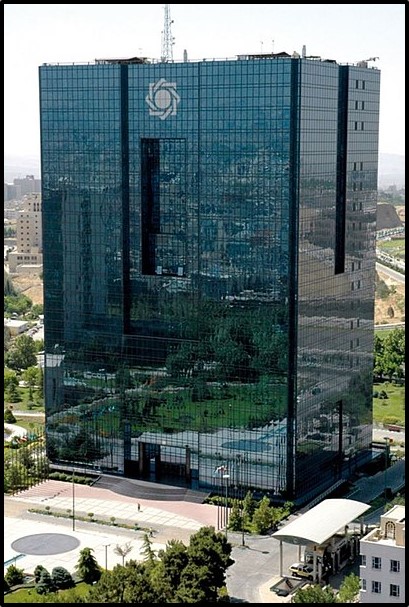

On April 6, Iran began indirect talks in Vienna with the United States on returning to compliance with the JCPOA. The Iranian delegation included representatives from the Central Bank of Iran and the Petroleum Ministry, which reflected Tehran’s interest in sanctions relief. The following is a list of major banking, shipping and oil institutions sanctioned by the Trump administration under multiple authorities.

Central Bank of Iran

Established in 1960 under the shah, the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) is responsible for designing and implementing monetary and credit policy. The bank’s governor is appointed for a five-year term by the cabinet. The bank is accountable to the government, which is the sole shareholder. Its duties include issuing currency and setting the exchange rate; supervising the financial sector; and facilitating trade-related transactions.

The Central Bank is the primary conduit for oil sales transactions, a key source of Iran’s foreign exchange. But since 2018, U.S. sanctions have made it hard for Iran to sell its oil abroad and be paid in hard currency because the bank was cut from the international financial system. The bank has been unable to repatriate tens of billions of dollars in frozen assets in foreign banks due to U.S. sanctions. The following is a timeline of U.S. sanctions on the Central Bank:

• In February 2012, the Obama administration sanctioned all Iranian financial institutions, including the Central Bank, to pressure Tehran to negotiate limits on its nuclear program. Iran “will face ever-increasing economic and diplomatic pressure until it addresses the international community’s well-founded and well-documented concerns regarding the nature of its nuclear program,” the Treasury said. Sanctions on the CBI were lifted in January 2016 as one of the incentives for Iran to agree to limits on its nuclear program and as part of the JCPOA.

• In May 2018, Trump abandoned the JCPOA.

• In November 2018, five months after withdrawing from the JCPOA, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on the Central Bank.

• In September 2019, the Trump administration sanctioned the bank for facilitating funding for Iran’s links to terrorism. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said that the CBI funded Iran’s “terrorist network, including the Qods Force, Hizballah, and other militants that spread terror and destabilize the region.” Washington said the sanctions were also a response to Iran’s attack that month on Saudi Aramco oil facilities by cruise missiles and drones.

National Iranian Oil Company

Established in 1951 after Iran nationalized its oil industry, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) is responsible for exporting oil and gas as well as exploration, drilling, production and research and development. It is overseen by the Ministry of Petroleum. NIOC was the ninth-largest state-owned oil company in the world, based on 2019 revenues. Iran has fourth-largest oil reserves and the second-largest gas reserves in the world. The following is a timeline of sanctions on NIOC:

• In November 2012, the Obama administration sanctioned NIOC for weapons of mass destruction proliferation by providing financial, material or other support to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). “As the IRGC has become increasingly influential in Iran’s energy sector, IRGC’s construction and development wing, Khatam Al-Anbia, has obtained billions of dollars’ worth of contracts from NIOC, often without participating in a competitive bidding process,” the Treasury said. Sanctions on NIOC were lifted in January 2016 as one of the incentives for Iran to agree to limits on its nuclear program and as part of the JCPOA.

• In May 2018, Trump abandoned the JCPOA.

• In November 2018, five months after withdrawing from the JCPOA, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on NIOC.

• In October 2020, the Trump administration sanctioned NIOC for facilitating terrorism through financial support to the IRGC, especially its external operations arm, the Qods Force. “The Iranian regime continues to prioritize its support for terrorist entities and its nuclear program over the needs of the Iranian people,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said.

National Petrochemical Company

Established in 1964, the National Petrochemical Company (NPC) is a subsidiary of the Ministry of Petroleum. Petrochemical exports, including chemicals, fertilizers, fuel and polymers, are the second-largest source of government revenue after crude oil. As of early 2021, petrochemical exports accounted for nearly a third of non-oil exports. NPC has historically been the second largest producer and exporter of petrochemicals in the Middle East, after Saudi Arabia. The following is a timeline of sanctions on NPC:

• In June 2010, the Obama administration sanctioned NPC to pressure Tehran to curb its nuclear and missile programs. The NPC was among 22 companies determined to be owned or controlled by the Iranian government. The Treasury said the sanctions were “designed to deter other governments and foreign financial institutions from dealing with these entities and thereby supporting Iran's illicit activities.” Sanctions on the NPC were lifted in January 2016 as one of the incentives for Iran to agree to limits on its nuclear program and as part of the JCPOA.

• In May 2018, Trump abandoned the JCPOA.

• In November 2018, five months after withdrawing from the JCPOA, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on NPC.

• In October 2020, the Trump administration sanctioned NPC for facilitating terrorism by being controlled by the Ministry of Petroleum, which generated revenue for IRGC.

National Iranian Tanker Company

National #Iranian Tanker Company (#NITC) makes its first confirmed OIL DELIVERY to #China’s Jinxi Refining and Chemical Complex after Trump administration’s revocation of waivers permitting sale of Iranian crude on May 2: Report pic.twitter.com/zWAOos01Hk

— Tasnim News Agency (@Tasnimnews_EN) June 26, 2019

Established in 1955, the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) transports Iranian crude oil for export and stockpiles oil in floating storage units. It is a subsidiary of the NIOC. As of 2019, NITC had a fleet of at least 54 tankers, including 38 Very Large Crude Carriers and eight Suezmaxes. NITC tankers began shipping millions of barrels of oil to Venezuela starting in May 2019. The following is a timeline of sanctions on NITC:

• In July 2012, the Obama administration sanctioned NITC, 58 vessels and 27 affiliates under helping Iran evade sanctions. Sanctions on NITC were lifted in January 2016 as one of the incentives for Iran to agree to limits on its nuclear program and as part of the JCPOA.

• In May 2018, Trump abandoned the JCPOA.

• In November 2018, five months after withdrawing from the JCPOA, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on NITC.

• In June 2020, the Treasury sanctioned captains working for NITC for shipping gasoline to Venezuela.

• In October 2020, the Treasury sanctioned NITC for facilitating funding for Iran’s links to terrorism. It accused NITC personnel of coordinating with Hezbollah on logistics and pricings for oil shipments to Syria.

Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines

Established in 1967, the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) is the national shipping company. It started under the name Aria Shipping Lines with six vessels. As of 2019, it operated a fleet of 115 vessels but many were old and unsafe for travel. IRISL has dozens of affiliates it uses to evade U.S. and international sanctions. The company has falsified documents to conceal military-related shipments from maritime authorities. The following is a timeline of sanctions on IRISL:

• In September 2008, the George W. Bush administration sanctioned the IRISL and 18 affiliates for shipping cargo used in Iran’s proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. In 2010, the Obama administration sanctioned dozens more IRISL affiliates as part of sanctions on Iran’s nuclear and missile programs. Sanctions on IRISL and its affiliates were lifted in January 2016 as one of the incentives for Iran to agree to limits on its nuclear program as part of the JCPOA.

• In May 2018, Trump abandoned the JCPOA.

• In November 2018, five months after withdrawing from the JCPOA, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on IRISL and its affiliates.

• In September 2019, the Treasury sanctioned an “oil-for-terror” shipping network that included IRISL-linked vessels.

• In December 2019, the State Department designated IRISL for transporting material used in Iran’s missile program. The designations took effect after 180 days to allow Iran to find alternative ways to ship humanitarian supplies.

• In June 2020, the Treasury sanctioned captains working for IRISL for shipping gasoline to Venezuela.

Private banks

In November 2018, the Trump administration reimposed punitive economic sanctions on most major public and private Iranian banks. Many private banks had been sanctioned by previous administrations for money laundering and sanctions evasion. U.S. sanctions cut them off from the global financial system. The difference between public and private banks in complicated in Iran because many private banks are owned by official or military organizations, while other banks are reportedly controlled by private conglomerates or charitable foundations (bonyads) that are also linked to the government.

Between 2018 and 2020, the Treasury took the additional – and unusual – step of sanctioning banks for facilitating funding for terrorism; it cited malign activities by the Revolutionary Guards and proxy militias across the Middle East. In 2020, President Trump’s Executive Order 13902 further authorized the Treasury to sanction any Iranian financial institution. U.S. sanctions were intended to have a chilling effect on foreign transactions with Iran. The following is the timeline of U.S. sanctions on private banks:

• In February 2012, the Obama administration froze the assets of all Iranian financial institutions held in the United States to pressure Tehran to negotiate limits on its nuclear program. In January 2016, the Obama administration lifted sanctions on dozens of Iranian banks as part of the Iran nuclear deal.

• In May 2018, Trump abandoned the JCPOA.

• In October 2018, the Treasury sanctioned several banks—including Bank Mellat, Parsian Bank, Sina Bank and Mehr Eqtesad Bank--for supporting the Basij under its counterterrorism authorities. Mehr Eqtesad had not previously been sanctioned.

• In November 2018, the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on 50 Iranian banks and their subsidiaries, including Amin Investment Bank, Arian Bank, Ayandeh Bank, Bank Kargoshaee, Bank Maskan, Bank Melli, Bank Sepah, Bank Tejarat, Day Bank and Future Bank.

• In October 2020, the Treasury sanctioned 18 major banks to deny Iran funding for its nuclear program, missile development or support for terrorism. The sanctioned banks included Amin Investment Bank, Bank Keshavarzi Iran, Bank Maskan, Bank Refah Kargaran, Bank-e Shahr, Eghtesad Novin Bank, Gharzolhasaneh Resalat Bank, Hekmat Iranian Bank, Iran Zamin Bank, Islamic Regional Cooperation Bank, Karafarin Bank, Khavarmianeh Bank (also known as Middle East Bank), Mehr Iran Credit Union Bank, Pasargad Bank, Saman Bank, Sarmayeh Bank, Tosee Taavon Bank (also known as Cooperative Development Bank), and Tourism Bank.