Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has detained or imprisoned tens of thousands of human rights activists, including peaceful protestors, dissidents, union members, civil society organizers, feminists, students, journalists, lawyers and the unemployed. It notoriously cracked down when millions took to the streets in dozens of cities after the disputed 2009 presidential election and again during nationwide protests over economic conditions in 2017-2018 and 2019. More than 19,000 people were rounded up during those three demonstrations. But many others have been arrested at smaller protests since 1999.

In January 2020, the judiciary said that about 30 people were arrested for taking part in protests after Iran admitted that the Revolutionary Guards had mistakenly shot down Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752. Iranians were enraged at the government’s incompetence and for denying responsibility for three days. Security forces reportedly used live ammunition and tear gas to disperse protestors in Tehran and several other major cities.

In November 2020, a U.N. General Assembly committee that deals with human rights called on Iran to release prisoners detained for participating in peaceful protests. The committee – which included Britain, France, Germany and the United States – urged Iran to cease the “widespread and systematic use of arbitrary arrests and detention.”

The United Nations also condemned the execution of Ruhollah Zam, a journalist and activist, who was hanged on December 12, 2020. Zam ran Amad News, an opposition news website that Iran blamed for inciting widespread anti-government protests in 2017-2018. He had been living in France, which granted him asylum after he documented the demonstrations. Ruhollah was reportedly captured by Iranian agents after traveling to Iraq in September 2019. The judiciary found Zam guilty of “corruption on earth,” a charge often leveled against critics of the government. His execution was “emblematic of a pattern of forced confessions extracted under torture and broadcast on state media being used as a basis to convict people,” Michelle Bachelet, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, said on December 14.

The judiciary, headed by a cleric and dominated by conservatives and revolutionary “principlists,” has invoked a broad and often vague range of charges against activists, such as “colluding against national security” or “distributing propaganda against the state.” Female activists who have challenged the Islamic Republic’s restrictive social laws have been imprisoned for crimes such as “promoting prostitution” or “insulting Islam.”

Since February 2018, Iran has also imprisoned at least nine prominent human rights lawyers who were representing activists, dissidents or political prisoners, according to the Center for Human Rights in Iran. Others have been subject to harassment or faced shorter detentions. Amnesty International called the campaign “part of an escalating crackdown to quash Iran’s civil society.” The Islamic Republic has regularly charged lawyers with vague crimes against the state, held them for arbitrary and lengthy periods before trial, and denied them access to an attorney of their choice, the State Department’s 2019 Human Rights Report concluded. Lawyers and others affiliated with the Defenders of Human Rights Center advocacy group have been subjected to “excessive sentences and punishments for engaging in regular professional activities,” it reported.

Tehran’s increasing harassment of human rights defenders has been widely condemned by international organizations. In mid-2019, a report by the U.N. Special Rapporteur for Iran accused the government of using “increasing levels of intimidation, arrest and detention for providing legal counsel to dissenting voices.” Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran, warned that the courts have been colluding with intelligence agencies to prosecute lawyers “so that any last hopes for defending due process are extinguished, with the tacit approval of Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi and the Rouhani government.”

Iran’s abuse of its own judicial system has further undermined Iran’s image and standing in the international community. “Iranian authorities continue to dig a hole for their domestic and international credibility as they lock up scores of lawyers and activists for the ‘crime’ of defending citizens’ fundamental rights,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, the Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “At a time when everyday life is increasingly difficult for millions of Iranians, rights advocates should be an essential part of solving collective problems, instead of a primary target of the government’s crackdown.”

Iran has faced widespread criticism from foreign governments and human rights groups for more than 40 years. The Islamic Republic has “heavily suppressed the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly” for dissidents challenging the theocracy, Amnesty International reported in 2019. The state’s restrictions on speech, its harsh sentences, and its monitoring of internet communications and social media are “among several factors that deter citizens from engaging in open and free private discussion,” the 2020 Freedom House report said. Iranian state television has a long record of airing “confessions extracted from political prisoners under duress, and it routinely carries reports aimed at discrediting dissidents and opposition activists.”

The State Department’s 2019 Human Rights report charged that Iran’s judiciary often “appeared to have determined the verdicts in advance, and defendants did not have the opportunity to confront their accusers or meet with lawyers. For journalists and defendants charged with crimes against national security, the law restricts the choice of attorneys to a government-approved list.”

Prison conditions are “harsh and life threatening,” the State Department added. Inmates often face physical and/or psychological torture. Prisoners given multiple sentences are eligible for release after serving the longest sentence, but the judiciary has in some cases tacked on additional charges as a prisoner nears release. In prison, some activists have continued to advocate for human rights in open letters and social media posts relayed through relatives, which has led to retaliatory measures by the state on prisoners or their families.

The following are two sets of profiles: First, prominent human rights activists imprisoned between 2004 and 2020. Second, the nine lawyers who defended activists.

Jailed Human Rights Activists

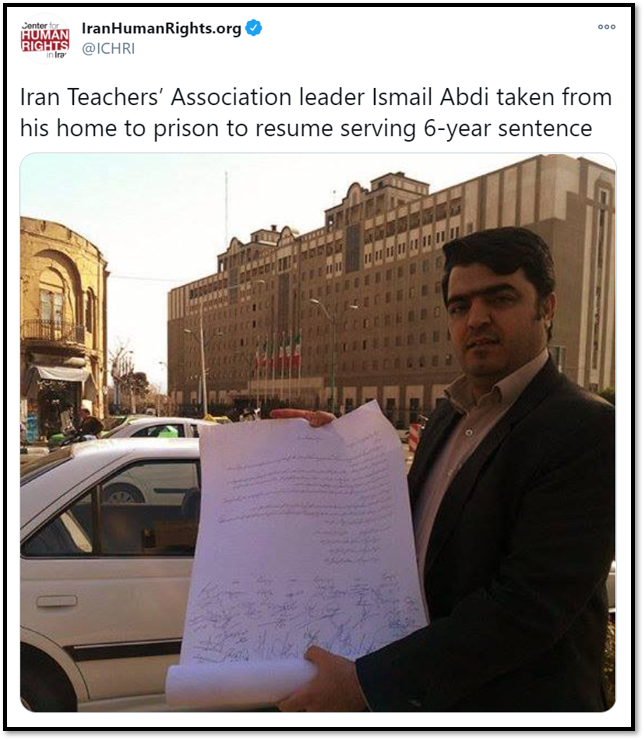

Ismael Abdi

Ismael Abdi, a teacher who was born in 1974, has campaigned for teachers’ rights and free education since at least 2007. He was Secretary General of Iran’s Teachers’ Trade Association from 2013 to 2016. He was detained five times and spent more than four years in prison between 2015 and 2020.

Ismael Abdi, a teacher who was born in 1974, has campaigned for teachers’ rights and free education since at least 2007. He was Secretary General of Iran’s Teachers’ Trade Association from 2013 to 2016. He was detained five times and spent more than four years in prison between 2015 and 2020.

Abdi was detained several times between March 2007 and May 2010 for attending protests and lobbying on behalf of the teachers’ union. He was usually held for a few weeks but not charged. In June 2015, he was arrested after he applied for a visa to attend a teacher’s conference in Canada. He was charged with “propaganda against the regime” and “gathering and collusion to act against national security.” In February 2016, he was sentenced to six years.

Langroudi and Abdi in an open letter on Oct. 4, 2018: “Iranian teachers are trying to prevent the development of education monetization. They want to provide free and quality education for all children, but the government, with its policy of privatizing education and attacking the low-income table, is increasing the number of working children and girls leaving school.”

Abdi went on a hunger strike on International Worker’s Day in May 2016 to protest the suppression of unions. He was released on bail after 16 days, but in November 2016 he was ordered to serve the rest of his sentence. He staged a second hunger strike from April until June 2017 over union rights. He contracted coronavirus in August 2020, but received limited medical treatment. He remained in prison as of November 2020.

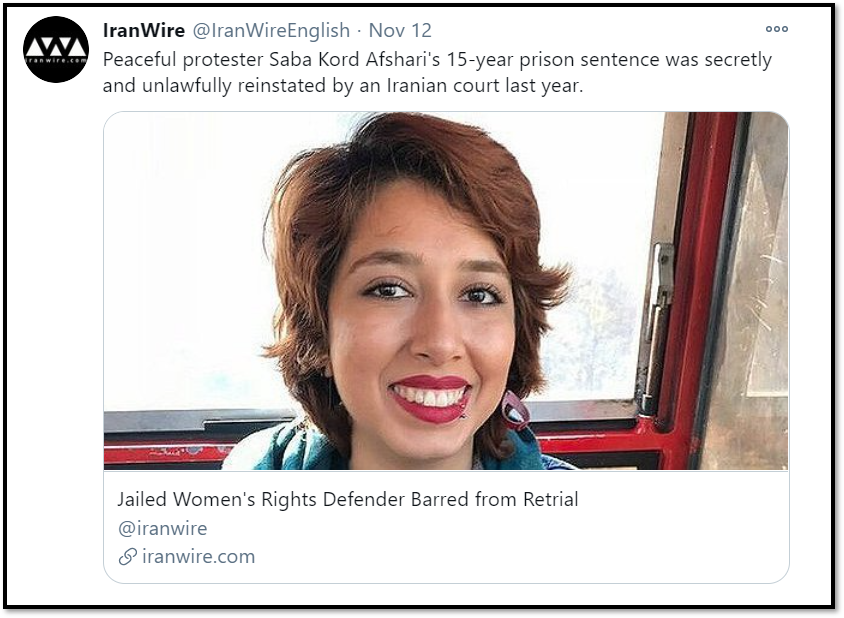

Saba Kord Afshari

Saba Kord Afshari, born in 1998, is a women’s rights activist who campaigned against mandatory hijab laws. She has been arrested twice and spent more than two years in prison.

Saba Kord Afshari, born in 1998, is a women’s rights activist who campaigned against mandatory hijab laws. She has been arrested twice and spent more than two years in prison.

In August 2018, she was arrested at a rally protesting government corruption, charged with “disruption of public order” and sentenced to one year. She was released in February 2019. In June 2019, Afshari posted a video of herself without the headscarf during the White Wednesdays protests. She was arrested for “encouraging people to commit immorality and/or prostitution” and sentenced to a total of 24 years in prison. Security officials detained her mother to pressure Afshari into confessing to the crime on state television. Her request for a retrial was rejected in November 2020 and she remained in Evin as of November 2020.

Kord Afshari in remarks after her first release in February 2019: “When I saw the situation of prisons closely, especially in Qarchak, I came to the conclusion that we in Iran only have the name of human rights. In fact, in Iran, there are no rights for humans, let alone respecting human rights in the prisons.”

Yasman Aryani

Yasman Aryani, who was born in the mid-1990s in Karaj, is a women’s rights activist who challenged mandatory hijab laws. She has been detained twice and has spent nearly two years in prison.

Aryani was first arrested in August 2018 at protests against government corruption. She served six months of a one-year sentence for “disrupting public order” before being pardoned in February 2019. In March 2019, on International Women’s Day, Aryani, her mother Monireh Arabshahi, and Mojgan Keshavaraz handed out flowers to riders on a female-only car on the Tehran Metro to encourage resistance to compulsory hijab laws. A video of the protest went viral.

Aryani, Kord Asfhari and Atena Daemi in an open letter on Oct. 17, 2019: “In all these years, the misogynist government has fought women and mothers who stand up for freedom and justice. That the fight continues is itself a sign of increasing awareness and acceleration of women’s struggles and protests.”

Aryani and her mother were detained at their home in April 2019 and charged with “assembly and collusion to act against national security,” “propaganda against the state,” “encouraging and providing for [moral] corruption and prostitution.” They were sentenced to 16 years. Aryani’s sentence was later reduced to nine years and seven months. She and her mother were transferred from Evin to Rajaee Shahr Prison in October 2020.

Jafar Azimzadeh

Jafar Azimzadeh, who was born in 1966, is a prominent labor activist and the Chairman of the Free Workers Union of Iran. He has been detained three times and spent more than four years in prison for organizing unions and strikes, demanding unpaid wages, and speaking to foreign media.

Jafar Azimzadeh, who was born in 1966, is a prominent labor activist and the Chairman of the Free Workers Union of Iran. He has been detained three times and spent more than four years in prison for organizing unions and strikes, demanding unpaid wages, and speaking to foreign media.

Azimzadeh was first detained on May 1, 2009, and again on May 1, 2014, for protesting on International Worker’s Day. He was held for a few weeks both times. In March 2015, he was tried for “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” He was sentenced to five years. He was imprisoned from November 2015 until June 2016, when he was temporarily released on bail after a two-month hunger strike. In September 2016, Azimzadeh and a colleague were re-tried for the same charges; they were sentenced to an additional 11 years. He was ordered to return to prison in December 2016 and served six months; he was temporarily released when the court acquitted him of one charge in June 2017.

Azimzadeh in an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran in October 2016: “All the charges and accusations against me are for trade union activities, such as organizing unions, non-violent labor strikes, and interviews with the media to defend workers’ rights, myself included. I am a worker.”

In January 2018, Azimzadeh was ordered to serve the rest of his sentence. He was eligible for pardon in February 2020, but he was sentenced to another one year and one month for signing a statement that protested prison medical policy. He contracted coronavirus in August 2020 and was hospitalized. He was returned to a public ward in September 2020.

Atena Daemi

Atena Daemi, who was born in 1988, is a children’s rights activist and an outspoken critic of the death penalty. She was first arrested in 2014 for meeting the families of prisoners, handing out flyers against the death penalty, and denouncing the regime on Facebook. She was imprisoned in 2016; her family claimed that she was prosecuted seven times while serving her sentence.

Atena Daemi, who was born in 1988, is a children’s rights activist and an outspoken critic of the death penalty. She was first arrested in 2014 for meeting the families of prisoners, handing out flyers against the death penalty, and denouncing the regime on Facebook. She was imprisoned in 2016; her family claimed that she was prosecuted seven times while serving her sentence.

Daemi was detained in October 2014 and held in solitary confinement. She was later charged with “assembly and collusion against national security,” “insulting the supreme leader” and “concealing criminal evidence.” In June 2015, she was sentenced to 14 years; the sentence was later reduced to seven years. She was temporarily released on bail in February 2016, but returned to prison in November 2016. She subsequently developed severe health problems, including skin disease, stomach problems and deteriorating eyesight.

In April 2017, Daemi went on hunger strike to protest the arrest of her two sisters, who after Daemi complained to the court that the Revolutionary Guards used excessive force during her arrest. Daemi’s health deteriorated during her hunger strike, but prison authorities reportedly refused her medical care.

Daemi in an open letter from prison on June 6, 2019: “They want to suffocate the voice concealed in my pen. But having learned that political prisoners in my country have defied such foolish jokes over the past two decades, like my friends, I keep learning from them to reach what I have been imprisoned for. The more pressure they impose, the closer their demise!!”

In September 2019, authorities added three years and eight months to her sentence for “disseminating propaganda” after she wrote an open letter criticizing executions and for “insulting the Supreme leader” when she sang in honor of executed prisoners. In December 2019, Daemi and other female prisoners, including Narges Mohammadi, led a sit-in to protest the regime’s crackdown on nationwide protests. Daemi was temporarily put in solitary confinement. After she joined a prison protest in February 2020, the court again extended her sentence by two years and added 74 lashes. She remained in Evin as of November 2020.

Sepideh Gholian

Sepideh Gholian, who was born in 1995 in Dezful, is a journalist and labor rights activist. She has been arrested twice since 2018. In 2019, she wrote a book called “Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim” which described torture and inhumane conditions in Sepidar Prison.

Sepideh Gholian, who was born in 1995 in Dezful, is a journalist and labor rights activist. She has been arrested twice since 2018. In 2019, she wrote a book called “Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim” which described torture and inhumane conditions in Sepidar Prison.

Gholian was first detained in November 2018 for reporting on a protest organized by the labor union of the Haft Tappeh sugar factory. She was released on bail in December, but arrested with her brother in January 2019 after she tweeted about the interrogations and abuse she suffered in detention. The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) aired her forced confession to incriminate her.

In September 2019, Gholian was charged with “assembly and collusion to act against national security,” “membership in an illegal group of Gam,” “propaganda against the state,” and “publishing false news.” She was sentenced to 19 years and six months; the court later reduced her sentence to five years. She staged a five-day hunger strike in October; she was temporary released on bail. Gholian wrote a memoir while on furlough, which was published by IranWire in 2020. It described the state’s practice of forcing confessions and discrimination against female prisoners.

Gholian in Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim, a book about her imprisonment in 2018: “I feel I have been sucked into an endless black hole and trapped there. It is a very small cell, maybe 5 square meters, with a filthy brown carpet and two filthier blankets.”

She was arrested a second time for participating in the November 2019 protests against oil price hikes. She subsequently sued the IRIB for defamation and disinformation. The IRIB retaliated with a counter-suit. Gholian was released on bail in the spring of 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic. In June 2020, she was reportedly offered a pardon if she apologized to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, but she refused. She was forced to return to prison, where she remained as of November 2020.

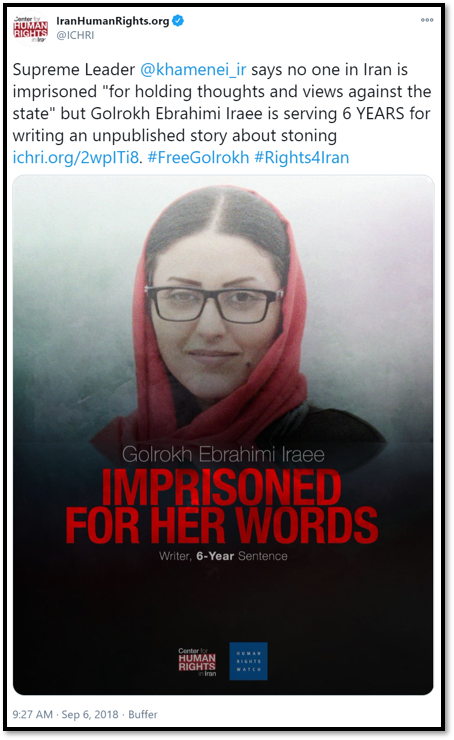

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, who was born in the early 1980s, is an accountant married to Arash Sadeghi, a fellow activist. She was imprisoned for merely writing a story, which was never published, that criticized the law on stoning adulterers to death. She has been arrested twice and spent three and a half years in prison.

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, who was born in the early 1980s, is an accountant married to Arash Sadeghi, a fellow activist. She was imprisoned for merely writing a story, which was never published, that criticized the law on stoning adulterers to death. She has been arrested twice and spent three and a half years in prison.

Intelligence officials reportedly found the handwritten text of her unpublished story when they raided her home in September 2014. She was charged with “insulting Islam,” “conspiracy against national security” and “propaganda against the regime” and sentenced to seven years. She was temporarily released in January 2017 after her husband went on hunger strike to protest her arrest, but she was forced to return to prison less than a month later.

Iraee and Daemi in a letter to foreign ambassadors who toured Evin Prison published on July 8, 2017: “We are in prison because we wanted to present the true picture of the deplorable human rights situation in the Islamic Republic of Iran. We have paid a heavy price for this and our families have also been intimated in various ways. We have even been kept hidden from you.”

Iraee and Atena Daemi, another women’s rights activist, protested in public letters and hunger strikes. The first letter and strike, in July 2017, cited poor conditions and inadequate medical care in Evin. The two women went on hunger strike again in February 2018 to protest their illegal transfer from Evin to Shahr-e Ray Prison, a former industrial chicken farm in Varamin. They also criticized the death penalty in open letters and by singing in prison. In September 2019, Iraee and Daemi were charged with “insulting the supreme leader" and "promoting propaganda against the state” and sentenced to an additional two years and one month. Iraee remained in prison as of November 2020.

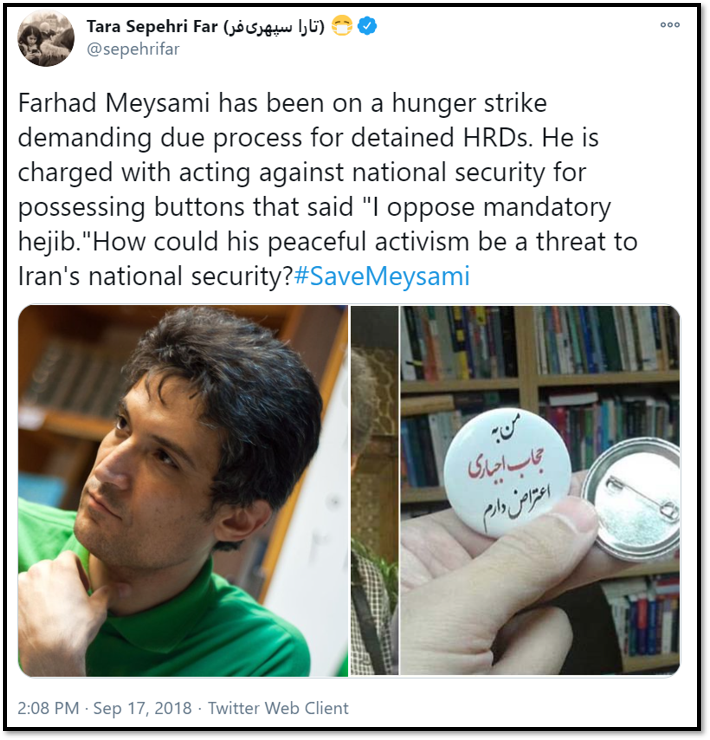

Farhad Merysami

Farhad Meysami, born in 1969, is a medical doctor and women’s rights activist who campaigned against laws requiring women to wear hijab to cover their hair. Meysami was arrested in July 2018 after security agents found books on human rights and buttons declaring “I protest forced hijab” in his office.

Farhad Meysami, born in 1969, is a medical doctor and women’s rights activist who campaigned against laws requiring women to wear hijab to cover their hair. Meysami was arrested in July 2018 after security agents found books on human rights and buttons declaring “I protest forced hijab” in his office.

Meysami was charged with “assembly and collusion against national security,” “promoting prostitution” and “propaganda against the state.” In January 2019, he was sentenced to six years; he was reportedly denied legal counsel during his trial.

He continued to protest injustice from prison. On August 1, 2018, he began a hunger strike that lasted 145 days to protest the arrest of fellow activist Reza Khandan.

In a message published on Facebook by fellow activist Reza Khandan on Aug. 24, 2018: “My hunger strike is out of respect for my own dignity and the dignity of those who have been detained on baseless accusations; those who are being interrogated while they have no access to a proper and legitimate legal representation. I will not, under any conditions, succumb to the demands of this illegal procedure.”

In October 2019, Meysami and Mohammad Habibi, his cellmate, wrote an open letter detailing prisoner abuse. He was moved to Rajaee Shahr Prison in Karaj a month later. He contracted the coronavirus in October 2020; he was isolated for eight days but then returned to a public ward.

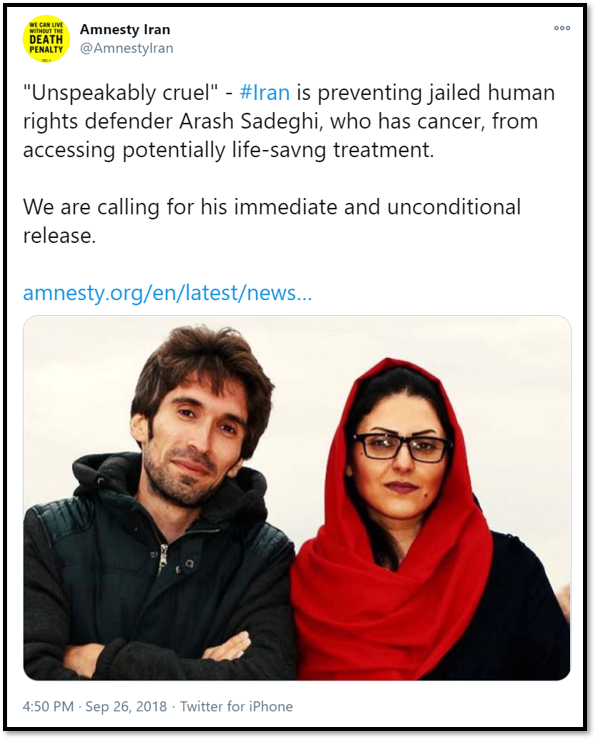

Arash Sadeghi

Arash Sadeghi, who was born in 1986, campaigned for former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi during the 2009 presidential election. He has been detained six times for protesting unfair elections and sharing information with international human rights groups. He has spent eight years in prison, during which he was denied treatment for bone cancer.

Arash Sadeghi, who was born in 1986, campaigned for former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi during the 2009 presidential election. He has been detained six times for protesting unfair elections and sharing information with international human rights groups. He has spent eight years in prison, during which he was denied treatment for bone cancer.

Sadeghi was first detained in July 2009 at protests over alleged electoral fraud, but was released without formal charges. His mother reportedly suffered a heart attack during a security raid on their home in November 2009; she died four days later. He was detained again without being charged in December 2009. In 2010, Sadeghi was charged with “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” He was sentenced to six years, later reduced to one year. He was released in 2011, but detained again in January 2012 and held without charge until October 2013.

Sadeghi was detained in September 2014 and held for seven months. In December 2015, he was arrested and charged with “conspiracy against national security,” “propaganda against the regime,” and “insulting the founder of the Islamic Republic.” He was sentenced to 19 years.

Sadeghi’s wife, Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, is also an activist. She was arrested in 2016 for writing about the stoning of a young woman for adultery. Sadeghi went on a71-day hunger strike until Iraee was released.

Sadeghi in an open letter from August 2018: “If Western officials are serious about this commitment, they cannot rightly plead economic and trade interests as an excuse to turn a blind eye to operatives of this overseas assassination campaign, the very same people who eliminate dissidents within Iran’s borders. Any kind of silence or cooperation with the Islamic Republic enables domestic oppression and threatens the opposition abroad.”

In 2018, Sadeghi developed bone cancer. He was temporarily released for surgery in September 2018, but was reportedly denied post-surgical care. Sadeghi remained in Evin as of November 2020.

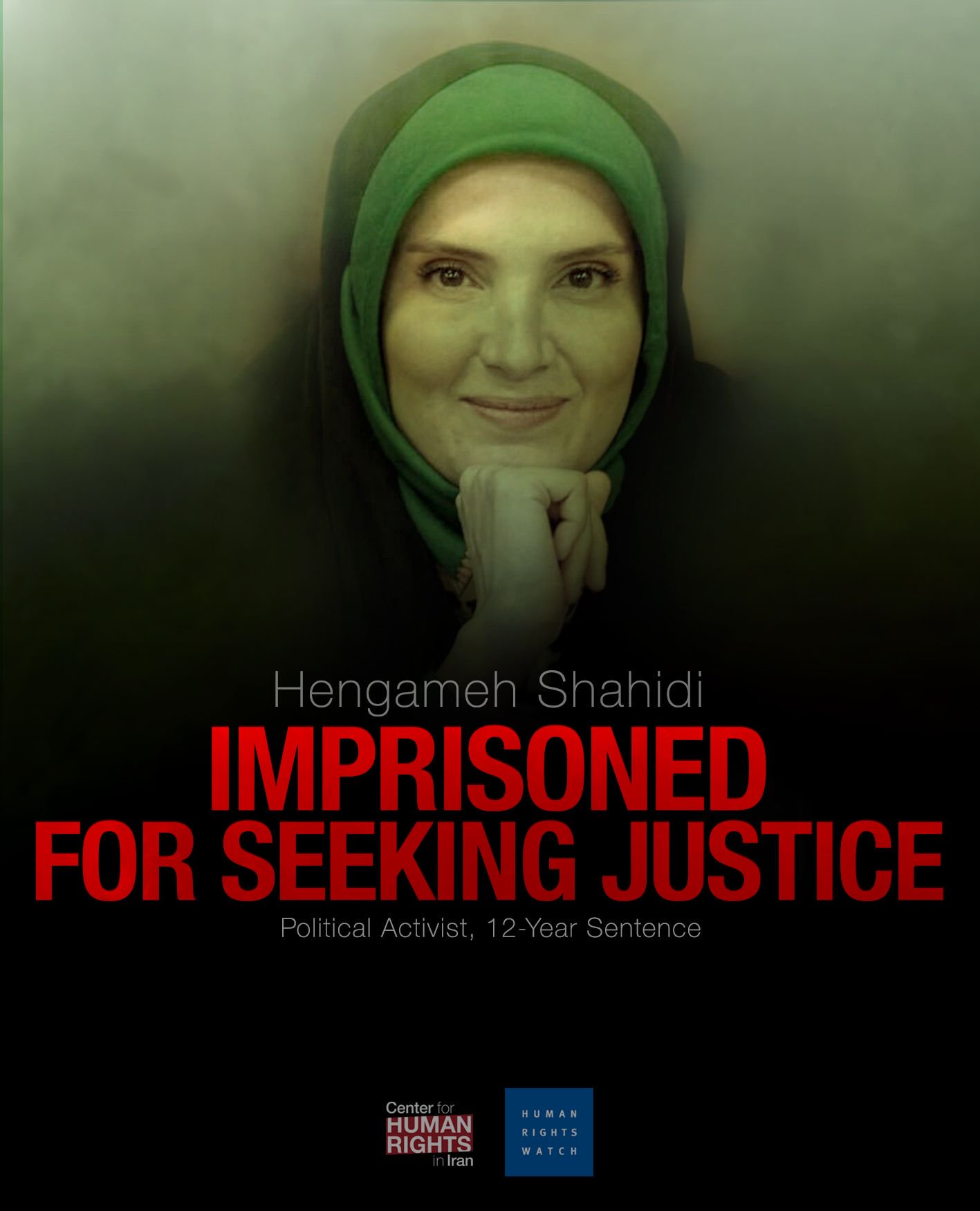

Hengameh Shahidi

Hengameh Shahidi, who was born in 1975, is a journalist who advised presidential candidate and former speaker of parliament Mehdi Karroubi in the 2009 election. She joined the 2009 Green Movement opposition after the election; she was prosecuted for protesting, speaking with media, supporting women’s rights, and campaigning against stoning for adultery. She has been detained three times and spent more than four years in prison.

Shahidi was first detained in July 2009 during the Green Movement protests over presidential election results. She was held in Evin for four months; she went on hunger strike until she was released on bail in November 2009. She was subsequently charged with “gathering and colluding with intent to harm state security” and “propaganda against the system;” she was sentenced to six years. She reportedly suffered health problems—including rheumatic heart disease, severe depression, and kidney and stomach problems—but she was allowed limited medical care. In May 2011, she was released on medical grounds.

Shahidi was first detained in July 2009 during the Green Movement protests over presidential election results. She was held in Evin for four months; she went on hunger strike until she was released on bail in November 2009. She was subsequently charged with “gathering and colluding with intent to harm state security” and “propaganda against the system;” she was sentenced to six years. She reportedly suffered health problems—including rheumatic heart disease, severe depression, and kidney and stomach problems—but she was allowed limited medical care. In May 2011, she was released on medical grounds.

Shahidi was detained without charge again in March 2017 before the presidential election in May. While in solitary confinement, she staged another hunger strike; she was hospitalized after two months for a heart condition. She was released in August 2017.

Shahidi was arrested again in June 2018 for criticizing the judicial system. In December, she was charged with “defamation,” “dissemination of false information,” “insulting regime officials,” “propaganda against the regime” and “conspiracy against national security.” She was sentenced to 12 years and nine months. She was only allowed two visits with her family and lawyer in six months, and her appeal was denied.

Shahidi in a letter posted on Instagram in March 2017: “You [President Hassan Rouhani] were supposed to be a breath of fresh air for reformists after the oppressive years under [President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad, and not choke the air out of them to become president like he did.”

In March 2020, Shahidi was reportedly infected with coronavirus. She was furloughed to receive medical attention in April, but in June 2020 was reported to be back to prison.

Caitlin Crahan, a research assistant the Woodrow Wilson Center, assembled the profiles of human rights activists.

Jailed Human Rights Lawyers

Amirsalar Davoudi

Davoudi is a Tehran lawyer who was born around 1990. He has represented clients charged with political or national security offenses, including Zeinab Jalalian, a Kurdish political prisoner, and Soheil Arabi, a blogger sentenced to death in 2014 for “insulting the Prophet of Islam.” (Arabi’s sentence was reduced in 2015 to seven-a-half years and mandatory religious education). Davoudi has championed freedom of speech and was known for representing human rights or political defendants for minimal cost or free of charge.

Urgent Action - Human rights lawyer Amirsalar Davoudi has been on hunger strike since 9 February, in protest at the Iranian authorities’ refusal to grant him prison leave. He is a prisoner of conscience who must be freed immediately and unconditionally. https://t.co/wrETDMl73B pic.twitter.com/8zcRmzkXHD

— Amnesty Iran (@AmnestyIran) February 18, 2020

On November 2018, Davoudi was arrested in Tehran and charged with “propaganda against the state.” He was held in a solitary cell in Evin Prison and was denied access to Vahid Farahani, his defense attorney. From November 2018 to April 2019, Davoudi was only permitted sporadic visits from Tanaz Kolahchian, his wife and a lawyer. On April 16, Farahani reported that Davoudi faced four charges, including “forming a group to overthrow the state.” The charges were related to a channel that Davoudi created and managed on the Telegram social media app. The channel was a public forum for thousands of people to discuss legal issues, mainly related to trade unions.

On June 1, 2019, Davoudi was sentenced to 30 years in prison and 111 lashes. Article 134 of Iran’s penal code allows people charged with multiple convictions to serve sentences concurrently, with the maximum time in jail from the longest sentence; his sentence was effectively 15 years. Davoudi chose not to object to the verdict. Amnesty International condemned the harsh sentence and launched a campaign to advocate for his release. A group of exiled Iranian lawyers wrote an open letter praising Davoudi’s integrity and criticizing the decision to convict him “merely for defending victims of the judiciary and security agents.”

In November 2019, a year after his arrest, Davoudi wrote an open letter to the people of Iran reaffirming belief in free speech and the right of citizens not to be prosecuted for expressing their views. The Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) dedicated its 2019 Human Rights Award to Davoudi as well as to Nasrin Sotoudeh, Mohammad Najafi and Abdolfatah Soltani, all Iranian human rights lawyers.

In February 2020, Davoudi went on a 10-day hunger strike after authorities denied his request for temporary release so he could see his young daughter, whom he had not seen in fifteen months. In March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, United for Iran, an advocacy group, demanded the release of Davoudi and 18 other imprisoned lawyers.

Payam Derafshan

Derafshan is a Tehran lawyer who started studying law at the University of Tehran in 2000. He has taken high-profile cases of human rights activists charged with political or national security offenses, including Nasrin Sotoudeh and Mohammad Najafi, both human rights lawyers. He also represented Kavous Seyed-Emami, an Iranian-Canadian professor and environmentalist who was accused of espionage in January 2018 and died in Evin Prison less than three weeks later.

Payam Derafshan is a lawyer who has defended several political and human rights activists including Mohammad Najafi, Nasrin Sotoudeh, and Vida Movahed. He was suspended from practicing law for two years. #FreeIranLawyers pic.twitter.com/mg7p0zPFuB

— International Observatory of Human Rights (@observatoryihr) June 25, 2020

In May 2018, Derafshan signed a petition that challenged the judicial ban on the Telegram social media app. In August, Derafshan was arrested in the Tehran suburb of Karaj while visiting the family of Arash Keyhosravi, another human rights attorney who had also signed the petition and been detained. Derafshan was charged with “insulting judicial authorities.” In January 2020, the Islamic Revolution Court in Karaj convicted him of “insulting the Supreme Leader.” His lawyers were barred from attending the trial, Saeed Dehgan, his defense attorney, said in May 2020. “They were allowed to read a few pages of the case file after the verdict was issued, which is a violation of the law.” Derafshan was sentenced to two years in prison and banned from practicing law for an additional two years.

In May 2020, an appeals court suspended Derafshan’s sentence--which meant that it would not be enforced unless the same offence was committed again-- but it upheld the professional ban. On June 8, 2020, Derafshan was arrested again and held in Evin Prison, again without access to his lawyer. The government did not clarify whether he was detained because of new charges or the previous case.

Soheila Hejab

Hejab is a Kurdish lawyer and activist in the city of Shiraz who was born in 1990 in the eastern province of Kermanshah. Hejab is reportedly a supporter of Reza Pahlavi, heir to the exiled Pahlavi monarchy and founder of Farashgard, an exiled opposition group. Hejab has called for regime change as well as legal rights for defendants and ethical treatment of political prisoners.

Human rights lawyer, Soheila Hejab is serving an 18-year prison sentence for defending women's rights in #Iran.

— International Observatory of Human Rights (@observatoryihr) June 25, 2020

In her own words: "When a pen does not write about injustices, it must be broken.” #FreeIranLawyers pic.twitter.com/bTKsLhFfEs

In December 2018, Hejab was arrested in Shiraz and charged with “supporting an anti-state organization.” She served five months of a two-year sentence. On June 6, 2019, ten days after her release, Revolutionary Guard intelligence agents raided Hejab’s home and rearrested her. She was detained in the women’s ward of Evin Prison. Hejab claimed that she was subjected to physical abuse at Evin and was once temporarily transferred to the hospital.

In December 2019, Hejab wrote a letter from Evin that criticized the government for denying legal rights to defendants and brutalizing demonstrators during the nationwide protests that began in November 2019. She also said that she had gone on a hunger strike but ended it after authorities falsely promised to release her. In February 2020, Hejab and 11 female political prisoners wrote an open letter calling on voters to boycott the parliamentary elections.

In March 2020, Hejab was released on bail. Five days later, a Tehran Revolutionary Court sentenced her to 18 years in prison for four offenses, including “gathering and planning against national security” and “joining opposition groups to defend women’s rights.” Article 134 of Iran’s penal code allows people charged with multiple convictions to serve sentences concurrently, with the maximum time in jail from the longest sentence; Hejab’s sentence was effectively seven years and six months. On May 23, 2020, an appeals court upheld her sentence, and Hejab was transferred to Qarchak Prison outside Tehran.

Hejab reported hat she was severely beaten after her appeal. She also claimed that an interrogator repeatedly threatened to kill her. On June 16, 2020, she began another hunger strike to protest her incarceration and harassment of her family. In an audio message in June 2020, Hejab demanded that authorities release her brother from prison and transfer Zeinab Jalalian—a Kurdish political prisoner diagnosed with coronavirus—out of Qarchak. Hejab also called on Iranians to demand their rights and take action against a regime that has “committed terrible murders.”

Arash Keykhosravi

Keykhosravi is a Tehran lawyer who was born in Saqqez City in Kurdistan province. He has taken high-profile human rights cases of people facing political charges. In early 2018, he and Payam Derafshan represented Kavous Seyed Emami, an Iranian-Canadian professor and environmentalist who was accused of espionage in January and died in Evin prison less than three weeks later. In February 2018, the two lawyers also took the case of Mohammad Najafi, another imprisoned human rights attorney, but they were ultimately blocked from representing him. Keykhosravi has advocated transparency in elections and the ethical treatment of prisoners.

As part of a yearlong crackdown on the right to counsel in #Iran, three defense attorneys—Mohammad Najafi, Arash Keykhosravi and Ghasem Sholeh Sa’di—have been sentenced to long prison terms under trumped-up national security charges https://t.co/hynBsbyxV6. pic.twitter.com/pNiHBDntId

— IranHumanRights.org (@ICHRI) December 11, 2018

In May 2018, Keykhosravi and other lawyers—including Derafshan—signed a petition that challenged the judicial ban on the Telegram social media app. On August 18, Keykhosravi and Ghasem Sholeh-Saadi, a former member of parliament, were arrested during a peaceful rally outside Parliament to protest the new Caspian Sea Agreement, which reduced Iran’s shares of the Caspian Sea’s resources by nearly 50 percent. Demonstrators also protested powers granted to the Guardian Council to vet all political candidates. Keykhosravi was charged with “propaganda against the system” and “assembly and collusion against national security.”

On August 30, several dozen lawyers signed an open letter demanding the release of Keykhosravi and Sholeh-Saadi. Keykhosravi was sentenced to six years in prison in December 2018. In January 2020, a Tehran appeals court acquitted Keykhosravi of all charges.

In April 2020, Keykhosravi co-wrote a letter that demanded the release of all eligible prisoners during the COVID-19 pandemic. The letter condemened the unhealthy prison conditions and the vulnerability of prisoners to the disease. In June 2020, Center for Human Rights in Iran reported that Keykhosravi was charged with “publishing falsehoods” because he criticized the arrest of Mohammad Najafi, a fellow human rights lawyer. Details about the new case against Keykhosravi, however, were unclear.

Mohammad Najafi

Mohammad Najafi, a lawyer and pro-democracy activist, was born around 1975 in Arak. He has protested government corruption, mistreatment of factory workers and police brutality. Najafi was arrested in 2009 for participating in the Green Movement protests and again in 2016 for wearing a shirt that commemorated the Green Movement. Najafi claimed that the authorities were “trying to grind him into oblivion” through repeated arrests and judicial harassment.

Mohammad Najafi, detained lawyer wearing Green Movement T-shirt, has been released on bail pic.twitter.com/HDqB5RP8f4

— IranHumanRights.org (@ICHRI) October 17, 2016

In December 2017, Vahid Heydari, one of Najafi’s clients, was arrested during economic protests; he died days later in Arak Prison. In January 2018, Najafi challenged the official claim that Heydari had committed suicide. A week later, Najafi was arrested and charged with eight offenses, including “organizing with the intention to disturb national security,” “propaganda against the state” and “insulting the supreme leader.” Four other human rights activists in Arak were also arrested in connection to his case. Najafi was denied access to his own attorneys. He was released on bail in April.

After his release, Najafi announced that he would continue working on Haydari's case. He was arrested again in October 2018 and sentenced to three years in prison and 74 lashes for “publishing falsehoods” and “disturbing the public state.” In December, Najafi was sentenced to an additional 14 years in prison. In January 2019, a Shazand court sentenced Najafi to two more years in prison for “disturbing public opinion” because of a letter he posted on Facebook. Addressed to Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khameini, the letter criticized government corruption and neglect of the poor.

In August 2019, Najafi was transferred to solitary confinement in Arak Prison, where he went on a hunger strike until he was returned to a general prison ward four days later. In September, Najafi protested his detention with another letter to Khameini. In November 2019, the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) dedicated its 2019 Human Rights Award to Najafi as well as to Nasrin Sotoudeh, Amir Salar Davudi and Abdolfatah Soltani, all Iranian human rights lawyers.

In December 2019, Najafi refused to appear in court on three separate dates. He was sentenced to three years and ten months for “insulting the supreme leader” and “agitating the public consciousness.” Najafi was temporarily released in March 2020 during the Covid-19 outbreak. Advocacy groups, including United for Iran and the CCBE, have called for his release.

Ghasem Sholeh-Saadi

Sholeh-Saadi is a lawyer, academic and former member of parliament, who was born in 1954. He represented the district of Shiraz from 1988 to 1996. He later worked as a professor of law and international relations at Tehran University. Sholeh-Saadi has criticized the government’s opposition to reform movements, its efforts to suppress educational freedom, and its lack of transparency.

Attorneys Arash Keykhosravi & Ghasem Sholeh Sa’di https://t.co/TRRUC8bNYO have been sentenced to 6 YEARS prison in #Iran for peacefully doing their jobs under “assembly and collusion against national security” & “propaganda against the state" charges. pic.twitter.com/a2e4PbAHri

— IranHumanRights.org (@ICHRI) December 10, 2018

Sholeh-Saadi registered as an independent candidate in the presidential election of 2001. In December 2002, he published a letter that questioned Ayatollah Khamenei’s religious credentials and accused him of undermining democracy. He was arrested in Tehran in February 2003 and charged with “insulting the authorities,” “acting against national security” and spreading propaganda against the state. He served 36 days of an 18-month sentence. Sholeh-Saadi claimed that he was released on bail because of his poor health; his wife said that he suffered a spinal injury in prison that caused paralysis in his left hand.

Sholeh-Saadi returned to teaching at Tehran University. In 2009, Sholeh-Saadi attempted to register as a presidential candidate but was disqualified by the Guardian Council. He was arrested again in April 2011. The prosecutor general said that Sholeh-Saadi was arrested because he had not fulfilled his 2003 sentence. In August, his wife reported that he developed shingles but was denied proper medical attention. In October, Sholeh Saadi was sentenced to another year for “insulting the supreme leader” through his letters and statements. The court banned him from teaching or practicing law for ten years.

Sholeh-Saadi was released in August 2012. He registered as a candidate for president in the 2013 election; he later said that he had been warned against talking with foreign media. In February 2016, the Supreme Disciplinary Court for Judges barred Sholeh-Saadi and two-dozen other lawyers from running in elections for the Iranian Bar Association’s board of directors. Sholeh-Saadi criticized the decision but did not appeal it. “Once the Supreme Disciplinary Court for Judges issues a decision,” he said, “there’s basically no hope.” In 2017, Sholeh-Saadi again registered as a presidential candidate.

On August 18, 2018, Sholeh-Saadi was arrested during a peaceful rally outside Parliament. The rally was to protest the new Caspian Sea Agreement, which reduced Iran’s shares of the Caspian Sea’s resources by nearly 50 percent. Demonstrators also protested the power of the Guardian Council to vet political candidates. Arash Keykhosravi, another human rights attorney, was arrested along with Sholeh-Saadi.

On August 30, several dozen lawyers signed a letter demanding the release of Sholeh-Saadi and Keykhosravi. In December 2018, Sholeh-Saadi was sentenced to six years in prison. In January 2020, a Tehran appeals court acquitted Sholeh Saadi of all charges.

Abdolfattah Soltani

Abdolfattah Soltani is a Tehran lawyer and co-founder of the Defenders of Human Rights Center who was born in 1953. He has provided legal and financial support to political prisoners. He has taken high-profile cases of people charged with political crimes, including Akbar Ganji, a journalist imprisoned from 2001 to 2005 for implicating government officials in the murder of dissidents, and Zahra Kazemi, an Iranian-Canadian journalist who was arrested in June 2003 for photographing detainees’ families outside Evin Prison and died 18 days later. Soltani has championed defendants’ rights and challenged the persecution of the Baha’i minority.

This is Abdolfattah Soltani, an Iranian human rights lawyer. He was briefly allowed out of prison to mourn his 30-yr-old daughter's death. #Iran's President @HassanRouhani is standing by & watching as #FreeSoltani's life slips from him. Soltani's crime? Defending human rights. pic.twitter.com/2YZmg9xHd9

— IranHumanRights.org (@ICHRI) August 4, 2018

In July 2005, Soltani was charged with “transferring classified information” related to an ongoing case in which his clients were charged with giving nuclear secrets to the United States and Israel. Mohammad Dadkhah, Soltani’s lawyer, claimed that his arrest was instead retaliation for his investigation into Kazemi’s death. Soltani was denied access to his attorney for five months. He was released on bail in March 2006. Four months later, he was sentenced to five years in prison. An appeals court acquitted him in May 2007 but confiscated his passport.

Four days after the mid-2009 presidential election, Soltani was again detained for 70 days. He spent 17 days in solitary confinement. In July, he was offered a temporary furlough to attend his sister’s funeral but rejected it because of an order that he not speak to the media. He was released on bail in August. Soltani later claimed that he was arrested for questioning the election results and associating with Shirin Ebadi, a Nobel prize-winning human rights attorney and co-founder of the Defenders of Human Rights Center.

In October 2009, Soltani won the Nuremberg International Human Rights Award for fighting for human rights “with admirable courage and at high personal risk.” Soltani’s wife accepted the award on his behalf because he was still barred from travel abroad.

Soltani was arrested again in September 2011 on charges of “spreading propaganda against the system,” “setting up an illegal opposition group,” “gathering and colluding with intent to harm national security” and “accepting an illegal prize and illegal earnings.” The charges were connected to his founding of the Defenders of Human Rights Center and the Nuremberg award. In March 2012, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison and was barred from practicing law for 20 years. In June, an appeals court reduced the sentence to 13 years.

Soltani received the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Award in October, 2012. In November 2013, he went on a hunger strike to protest poor medical treatment for prisoners. Soltani’s family reported that he had severe coronary and digestive problems in 2013 and was hospitalized for 41 days. In June 2014, 100 lawyers wrote an open letter to Sadeq Larijani, head of the judiciary, demanding a new trial for Soltani. In January 2016, he received a 21-day medical furlough but was sent back to Evin Prison before full recovery; he was hospitalized again in May for heart issues. Soltani’s family has repeatedly petitioned for better medical treatment and medical furloughs.

In September 2016, the Defenders of Human Rights Center reported that Soltani’s sentence was reduced to 10 years, with a two-year ban on practicing law after his release. Article 134 of Iran’s penal code stipulates that anyone convicted of multiple offenses must serve only the maximum sentence for the biggest offense. In August 2018, Soltani was given a temporary furlough for the funeral of his daughter. He returned to prison on October 28 but was released on parole one month later.

In November 2019, the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) dedicated its 2019 Human Rights Award to Soltani as well as Nasrin Sotoudeh, Mohammad Najafi, Amir Salar Davoudi, all Iranian human rights lawyers.

Nasrin Sotoudeh

Nasrin Sotoudeh, who was born in 1963, is one of the most prominent human rights lawyers in Iran and a vocal critic of its judicial process, treatment of women and death penalty. She has represented Nobel Prize winner Shirin Ebadi as well as women’s rights activists, victims of domestic abuse, minors on death row, journalists and Kurdish rights activists.

📺 Watch Reza Khandan, husband of the jailed Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, talk about his wife’s hunger strike and her plea to release political prisoners and prisoners of conscience #COVID19 #StandUp4HumanRights. 👉 https://t.co/ktKAyx8p8x pic.twitter.com/So0RUUhoqB

— UN Human Rights (@UNHumanRights) May 21, 2020

Before the 2009 presidential election, Sotoudeh was an active member of the Iranian Women’s Coalition, which demanded gender equality in the law. After the post-election protests, Sotoudeh represented the families of demonstrators killed by government forces. She was arrested after a raid on her home in September 2010. She was charged with “propaganda against the system” as well as “acting against national security.” In January 2011, she received an 11-year prison sentence that was later reduced to six years after international outcry from the United Nations and international human rights groups. Sotoudeh was given early release in September 2013.

In 2013, Sotoudeh co-founded the Campaign for Step By Step Abolition of the Death Penalty, known by the Farsi acronym LEGAM. LEGAM was established to advocate legislation that would abolish capital punishment. In early 2018, she took the case of Narges Hosseini, an activist arrested for protesting the law requiring hijab, or head covering, who refused to attend her own trial. Hosseini “objects to the forced hijab and considers it her legal right to express her protest,” Sotoudeh said. “She is not prepared to say she is sorry.”

On June 4, 2018, Sotoudeh criticized Iran’s Criminal Procedures Regulations, which forces defendants facing security charges to select a lawyer from a list pre-approved by the judiciary. “A number of lawyers have said they are ready to hold a protest sit-in if necessary,” Sotoudeh said. On June 13, 2018, she was again arrested. According to Sotoudeh’s husband, government agents did not explain the charges but informed her that she had been sentenced to five years in prison. In August 2018, Payam Derafshan, Sotoudeh’s lawyer, reported that the five-year sentence was based on a charge of “espionage in hiding” issued in absentia in 2015. The subsequent charges against her included “membership in the Defenders of Human Rights Center, the LEGAM group (against capital punishment), and the National Peace Council,” as well as “encouraging people to corruption and prostitution.” The “corruption and prostitution” charge may have been connected to Sotoudeh’s defense of Hosseini.

Sotoudeh refused to appear at her trial in December 2018 to protest the state’s refusal to let her use her own attorney. On March 11, 2019, she was convicted of seven offenses and sentenced to 148 lashes and 33 years in addition to the earlier five-year sentence. Under Article 134 of Iran’s penal code, a person convicted of multiple offenses can serve the maximum sentence for the biggest offense. Sotoudeh later claimed that the longest sentence was twelve years for “encouraging… corruption and prostitution.”

The United States, United Nations, European Union and international human rights groups condemned Sotoudeh’s sentence, but she refused to appeal the case on grounds that she did not accept the legitimacy of the verdict or the judicial system. In November 2019, the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) dedicated its 2019 Human Rights Award to Sotoudeh as well as to Mohammad Najafi, Amir Salar Davoudi and Abdolfatah Soltani, all Iranian human rights lawyers.

In March 2020, Sotoudeh wrote an open letter for International Women’s Day. She called for an end to the “systematic” violation of women’s rights in Iran and appealed to the Iranian and U.S. governments to set aside their rivalries for the sake of their female citizens. Ten days later, Sotoudeh began a hunger strike to demand freedom for all political prisoners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three activists imprisoned in Evin joined her protest. Nasrin claimed that she understood the medical risks of beginning a hunger strike during the Coronavirus outbreak and that she resorted to the protest as a “last resort.”

In late July 2020, Sotoudeh’s husband, Reza Khandan, discovered that the judiciary had blocked her bank account starting in May 2020. “We believe the prosecutor’s action is aimed at putting economic pressure and financially hurting the family in a time of crisis and economic collapse due to the incompetence and inadequacy of the government and ruling establishments. We will not stay silent in the face of such inhuman actions,” Khandan wrote on Facebook.

On August 11, Sotoudeh went on hunger strike to demand the release of political prisoners amid the COVID-19 pandemic. In a letter from Tehran’s infamous Evin prison, she warned that inmates were being denied due process and access to legal representation. “It is impossible to continue their detention under these oppressive conditions,” wrote Sotoudeh. Sotoudeh said that interrogators acted with impunity in extrajudicial proceedings. Prisoners “are treated as if there are no laws and none of them have the right to any legal outlets,” she added.

On August 17, Intelligence Ministry and judiciary agents raided Sotoudeh’s house and arrested her 20-year-old daughter, Mehraveh Khandan, on charges of “insult and assault.” One of the family’s lawyers posted bail of 100 million tomans, about $23,729, to release her. Reza Khandan said the charges related to a verbal argument between his daughter and a female prison guard in 2019. “The message is very clear: Ms. Sotoudeh you must climb down and stop your hunger strike. They want to put pressure on her and intimidate the family.”

On September 19, Sotoudeh was transferred to an intensive care unit at Taleghani Hospital due to heart and breathing problems. “The security authorities have done everything to her with the aim of creating one of the most inhuman conditions in the hospital, to isolate her from the outside world, to prevent any contact so that she can submit to the will of the security guards,” according to Khandan. But she was transferred back to Evin prison on September 23, despite her poor health. She ended her hunger strike on September 26 but by mid-October was faced with “grave cardiac and pulmonary problems,” according to her husband.

Khandan said she was exposed to guards in the hospital who later tested positive for COVID-19. He charged that her return to prison was “a deliberate attempt to put her life in danger.” On October 20, prison authorities told Sotoudeh that she would be transferred to the hospital again, but they sent her to Gharchak prison, according to Khandan. “By denying Nasrin Sotoudeh critically needed medical care, and instead moving her to Gharchak Prison, known for its horrific conditions, the authorities in Iran are placing Nasrin Sotoudeh’s life in immediate danger,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran. On November 7, Sotoudeh was temporarily released. The judiciary did not provide details about the furlough. Three days later, her husband said that she tested positive for COVID-19 during a visit to the doctor. On December 2, she was summoned back to Gharchak prison.

Other Lawyers:

Hoda Amid, arrested in September 2018, three days before leading a workshop on gender equality in marriage. No charges were announced, and she was released on bail in November 2018.

Mohammad Ali Dadkhah, arrested in 2012 for “spreading propaganda against the system through interviews with foreign media” and “membership in the Center for the Defenders of Human Rights,” and sentenced to 8 years and a ten-year ban on practicing law. Dadkhah was released on furlough 2013, but the court upheld his professional ban.

Farrokh Forouzan, arrested along with Payam Derafshan in August 2018 while visiting the home of Arash Keykhosravi, a detained human rights lawyer. He was charged with “insulting the leadership” and sentenced to two years. His sentence was suspended in May 2020.

Mehdi Houshman-Rahimi, sentenced in absentia in December 2018 to five years for “spreading propaganda against the system,” “insulting the founder of the Islamic Republic,” and “[making] insulting remarks during a speech on November 17, 2016.” After failing to respond to summons, he was sentenced in absentia in January 2019 to two years for “insulting the head of the judiciary” and “insulting the supreme leader.” He was permitted to remain free until the end of his appeal process.

Farhad Mohammadi, arrested in January 2019 on unannounced charges. Mohammadi is the secretary of the National Unity Party in Kurdistan and was arrested along with at least eight other Kurdish activists. He was released on bail in July 2019.

Masood Shamsnejad, arrested in January 2019 and charged with “spreading propaganda against the system” and “membership of a Kurdish opposition party.” He was sentenced to six years in February 2019.

Zeinab Taheri, arrested in June 2018 for “inciting public opinion and mobilizing the counterrevolution against the judiciary.” She was detained a day after the execution of Mohammad Salass, her client. Taheri had promised to publish evidence proving Salass’s innocence. She was released on bail in August 2018.

Casey Donahue, a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson Center, assembled the report on jailed lawyers.

Photo Credits: Raisi and Larijani by Mehr News Agency, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons