Born in 1963, Nasrin Sotoudeh has been a vocal critic of Iran’s judicial process, treatment of women, and death penalty. She has represented Nobel Prize winner Shirin Ebadi as well as women’s rights activists, victims of domestic abuse, minors on death row, journalists and Kurdish rights activists.

Trial and Imprisonment

Before the 2009 presidential election, Sotoudeh was an active member of the Iranian Women’s Coalition, which demanded gender equality in the law. After the post-election protests, Sotoudeh represented the families of demonstrators killed by government forces. She was arrested after a raid on her home in September 2010. She was charged with “propaganda against the system” as well as “acting against national security.” In January 2011, she received an 11-year prison sentence that was later reduced to six years after international outcry from the United Nations and international human rights groups. Sotoudeh was given early release in September 2013.

On June 4, 2018, Sotoudeh criticized Iran’s Criminal Procedures Regulations, which forces defendants facing security charges to select a lawyer from a list pre-approved by the judiciary. “A number of lawyers have said they are ready to hold a protest sit-in if necessary,” Sotoudeh said. On June 13, 2018, she was again arrested. According to Sotoudeh’s husband, government agents did not explain the charges but informed her that she had been sentenced to five years in prison. In August 2018, Payam Derafshan, Sotoudeh’s lawyer, reported that the five-year sentence was based on a charge of “espionage in hiding” issued in absentia in 2015. The subsequent charges against her included “membership in the Defenders of Human Rights Center, the LEGAM group (against capital punishment), and the National Peace Council,” as well as “encouraging people to corruption and prostitution.” The “corruption and prostitution” charge may have been connected to Sotoudeh’s defense of Hosseini.

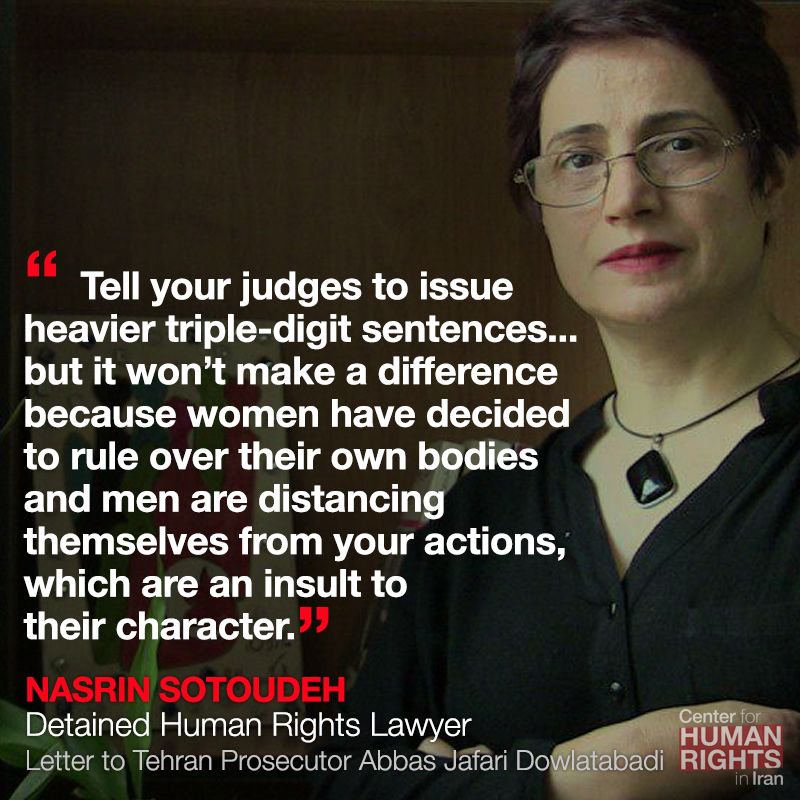

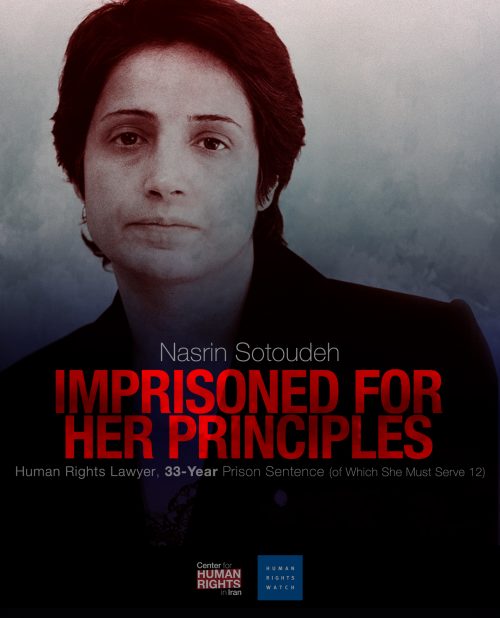

Sotoudeh refused to appear at her trial in December 2018 to protest the state’s refusal to let her use her own attorney. On March 11, 2019, she was convicted of seven offenses and sentenced to 148 lashes and 33 years in addition to the earlier five-year sentence. Under Article 134 of Iran’s penal code, a person convicted of multiple offenses can serve the maximum sentence for the biggest offense. Sotoudeh later claimed that the longest sentence was twelve years for “encouraging… corruption and prostitution.”

The United States, United Nations, European Union and international human rights groups condemned Sotoudeh’s sentence, but she refused to appeal the case on grounds that she did not accept the legitimacy of the verdict or the judicial system. In November 2019, the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe (CCBE) dedicated its 2019 Human Rights Award to Sotoudeh as well as to Mohammad Najafi, Amir Salar Davoudi and Abdolfatah Soltani, all Iranian human rights lawyers.

Open Letters and Hunger Strikes

In March 2020, Sotoudeh wrote an open letter for International Women’s Day. She called for an end to the “systematic” violation of women’s rights in Iran and appealed to the Iranian and U.S. governments to set aside their rivalries for the sake of their female citizens. Ten days later, Sotoudeh began a hunger strike to demand freedom for all political prisoners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three activists imprisoned in Evin joined her protest. Nasrin claimed that she understood the medical risks of beginning a hunger strike during the Coronavirus outbreak and that she resorted to the protest as a “last resort.”

📺 Watch Reza Khandan, husband of the jailed Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, talk about his wife’s hunger strike and her plea to release political prisoners and prisoners of conscience #COVID19 #StandUp4HumanRights. 👉 https://t.co/ktKAyx8p8x pic.twitter.com/So0RUUhoqB

— UN Human Rights (@UNHumanRights) May 21, 2020

In late July 2020, Sotoudeh’s husband, Reza Khandan, discovered that the judiciary had blocked her bank account starting in May 2020. “We believe the prosecutor’s action is aimed at putting economic pressure and financially hurting the family in a time of crisis and economic collapse due to the incompetence and inadequacy of the government and ruling establishments. We will not stay silent in the face of such inhuman actions,” Khandan wrote on Facebook.

On August 11, 2020, Sotoudeh went on hunger strike to demand the release of political prisoners amid the COVID-19 pandemic. In a letter from Tehran’s infamous Evin prison, she warned that inmates were being denied due process and access to legal representation.

To Human Rights Defenders:

In the midst of the Covid-19 crisis which has gripped Iran and the world, the conditions of political prisoners [in Iran] have become so difficult that it is impossible to continue their detention under these oppressive conditions. Their legal cases are made up of unbelievable charges of espionage, corruption on earth, acts against national security, corruption, prostitution, and formation of a unlawful group on the Telegram [social media platform] that can result in up to ten years of imprisonment or even execution.

Many defendants are denied access to an independent attorney or free (unchecked) communication with their own attorneys from the start of their cases through the sentencing. The Revolutionary Court judges recklessly and repeatedly tell the political defendants that they issue verdicts solely based on reports from the intelligence and security agencies and the interrogator tells them the final verdict in advance, from the moment of their arrest. Human rights attorneys are sent to prison because the Revolutionary Court judges become furious with them. Those who face unbelievably heavy charges receive maximum and even more than maximum sentences. Then, a political prisoner who has been sentenced under such unjust conditions incredulously hopes for a legal remedy.

Many defendants are denied access to an independent attorney or free (unchecked) communication with their own attorneys from the start of their cases through the sentencing. The Revolutionary Court judges recklessly and repeatedly tell the political defendants that they issue verdicts solely based on reports from the intelligence and security agencies and the interrogator tells them the final verdict in advance, from the moment of their arrest. Human rights attorneys are sent to prison because the Revolutionary Court judges become furious with them. Those who face unbelievably heavy charges receive maximum and even more than maximum sentences. Then, a political prisoner who has been sentenced under such unjust conditions incredulously hopes for a legal remedy.

Courts of appeals, conditional parole, sentence suspension, postponement of sentences, and a new law that insists on minimum charges have been annunciated, but in extrajudicial proceedings, the exercise of all these legal rights are left to interrogators who shut all doors [to freedom] for political prisoners. Many prisoners are now eligible for conditional parole and many would be released with the enforcement of the new law, but prisoners are treated as if there are no laws and none of them have the right to any legal outlets. Prisoners' correspondence to find legal ways out [of the situation] have remained unaddressed.

As all correspondences remain unanswered, I am going on a hunger strike, demanding the release of political prisoners.

Hoping for justice in my homeland, Iran.

Nasrin Sotoudeh, Evin [Prison]

August 11, 2020

On August 17, 2020, Intelligence Ministry and judiciary agents raided Sotoudeh’s house and arrested her 20-year-old daughter, Mehraveh Khandan, on charges of “insult and assault.” One of the family’s lawyers posted bail of 100 million tomans, about $23,729, to release her. Reza Khandan said the charges related to a verbal argument between his daughter and a female prison guard in 2019. “The message is very clear: Ms. Sotoudeh you must climb down and stop your hunger strike. They want to put pressure on her and intimidate the family.”

Documentary on her life

Nasrin was the subject of a 2020 movie, secretly filmed in Iran by women and men who risked arrest. "NASRIN is an immersive portrait of one of the world’s most courageous human rights activists and political prisoners, Nasrin Sotoudeh, and of Iran’s remarkably resilient women’s rights movement," according to the film producers.

Health issues

On September 19, 2020, Sotoudeh was transferred to an intensive care unit at Taleghani Hospital due to heart and breathing problems. But she was transferred back to Evin prison on September 23, despite her poor health. She ended her hunger strike on September 26 but by mid-October was faced with “great cardiac and pulmonary problems,” according to her husband. Khandan said that she was exposed to guards in the hospital who later tested positive for COVID-19. He charged that her return to prison was “a deliberate attempt to put her life in danger.”

On October 20, 2020, prison authorities told Sotoudeh that she would be transferred to the hospital again, but she was instead taken to Gharchak prison, according to Khandan. “By denying Nasrin Sotoudeh critically needed medical care, and instead moving her to Gharchak Prison, known for its horrific conditions, the authorities in Iran are placing Nasrin Sotoudeh’s life in immediate danger,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran.

Sotoudeh’s daughter, Mehraveh, was summoned to court on October 26, 2020. She and her lawyers, Mostafa Nili and Shadi Halimi, presented their defense against the complaint filed by Fatemeh Hosseinpour, a guard at the Evin Prison Women’s Ward. The judge said a verdict would be issued after receiving video footage of the incident in question.

In an op-ed on October 23, 2020, Helena Kennedy, the director of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute, and Irwin Cotler, Sotoudeh’s international legal counsel and a former justice minister and attorney-general of Canada, called on the Canadian government to demand her release and sanction her jailers. “It is past time that Canada imposed Magnitsky sanctions on the Iranian architects of repression, including Mr. Raisi [head of Iran’s judiciary] and the head of Evin Prison,” Kennedy and Cotler wrote in The Globe and Mail. “Violators in the international arena must be named and shamed.”

On November 7, 2020, Sotoudeh was temporarily released. The judiciary did not provide details about the furlough. Three days later, her husband said that she tested positive for COVID-19 during a visit to the doctor.

Photos of Iranian rights advocate Nasrin Sotoudeh with her daughter Mehraveh. Sotoudeh was temporarily released from prison yesterday amid concerns over her health. #freenasrin https://t.co/iNJKiSxWJR

— Golnaz Esfandiari (@GEsfandiari) November 8, 2020

On December 2, 2020, Sotoudeh was summoned back to Gharchak prison. Her husband published the following message from her on Facebook:

Dear friends and human rights activists,

They told me to go back to prison and today I will return to prison, where I left behind hundreds of cellmates, a place where I left my heart behind. It’s always this way. Under these circumstances, I don’t like to talk about what it was like being unable to hug my children during these three weeks because of the coronavirus.

But I do have a duty to declare my concern about Ahmadreza Djalali’s situation and appeal to everyone who can muster support to pay attention to his case. Free Ahmadreza Djalali, today.

Nasrin Sotoudeh

American Bar Association Award

In December 2020, the American Bar Association's Center for Human Rights honored Sotoudeh with its annual Eleanor Roosevelt Prize for Global Human Rights Advancement. “The professional solidarity which transcends our governments advances a brighter outlook for civil society and the true meaning of rights and justice,” she said in a pre-recorded message.

Open letter on minorities

In February 2021, Sotoudeh asked PEN America to circulate a letter about a new spate of executions of ethnic and religious minorities in Iran.

To The Honorable Secretary-General of the United Nations,

I write to you from Qarchak, one of Iran’s most notorious prisons, so that my voice might, in some way, boost the efforts of the United Nations. My hope is that, in the not too distant future, we can realize even some small part of the great dreams for humanity enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As you may be aware, in the past few months, many of our religious and ethnic minority compatriots in Iran have been executed amid the media’s silence. At dawn on Wednesday, February 17, Zahra Esmaeli, an inmate at our prison, and eight other prisoners were taken to the gallows and hanged.

You know well what predictable mistakes are often made in these numerous executions. As someone who has been closely involved in Zahra Esmaeili’s case, I am certain that she did not commit murder. I ask you, the international community, and human rights activists to please pay close attention to the issue of executions in Iranian society, especially that of religious, ethnic minorities, and women, and take necessary measures to prevent such extensive executions.

With deep respect,

Nasrin Sotoudeh

Qarchak Women’s Prison

On June 13, 2021, U.S. Special Envoy for Iran Rob Malley marked the third year anniversary of Sotoudeh's sentencing in a tweet:

It's been 3 yrs since human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh was sentenced to 38.5 yrs in prison and 148 lashes for defending women’s rights in Iran. From prison she cont’s to advocate for the humane treatment of political prisoners. She should not have spent a single day in prison.

— Special Envoy for Iran Robert Malley (@USEnvoyIran) June 13, 2021

On July 21, 2021, Sotoudeh was granted medical leave from prison. She was still at home as of July 2022.

Open letter to American women

In an open letter after the U.S. Supreme Court reversed Roe v. Wade in July 2022, Sotoudeh pledged to stand by American women as their rights are “facing assault” on their reproductive rights. “Abortion rights and contraceptive rights are now recognized in dozens of countries around the world, thanks to the hard-fought struggles of countless women and men. Now, they are once again at risk.”

In a piece published in Ms. Magazine, she expressed concern that "this threat is emerging in what has long been the most powerful heartland of the global movement for women’s rights: the United States. It is extremely sad to see your country move away from the principles of freedom and progress that (even when not fully realized) have long been such an inspiration. We should all be alarmed by what will fill the void.”

Reflecting on her own experience as a political prisoner, she wrote as “someone who lived through (and campaigned against) this loss of freedom and democracy, I can offer a warning: It will not end with this Supreme Court decision on abortion.” she pledged to "stand by you my sisters so that through our solidarity as women, we triumph over oppression and make the world safer and better for generations to come.”

State Department Award

On Feb. 1, 2023, the State Department announced the 10 winners of the annual Global Human Rights Defender Awards, including Sotoudeh. “As we celebrate both the 75th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 25th Anniversary of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, we are pleased to honor this cohort of Awardees – ten individuals from around the globe who have demonstrated leadership and courage while promoting and defending human rights and fundamental freedoms; countering and exposing human rights abuses by governments and businesses; and rallying action to protect the environment, improve governance, and secure accountability and an end to impunity,” the State Department said in a statement.