Henry Rome is the deputy head of research at Eurasia Group. Follow him on Twitter at @hrome2.

What are the key drivers of Iran’s economy in 2022? And how have they changed since 1979?

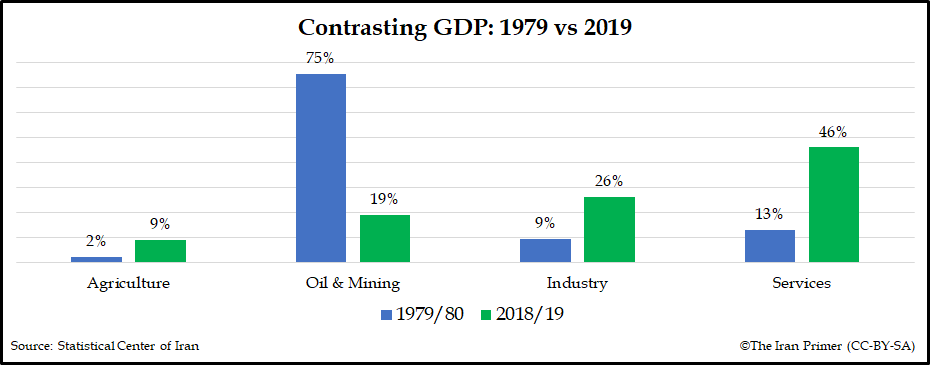

Iran’s economy is driven primarily by the services sector – education, health care, communications, banking, insurance and the like – which accounted for about half of economic output and total employment in 2019/20. The industrial sector – including manufacturing and construction – contributed about one-third to gross domestic product, while agriculture contributed just over 10 percent. Finally, the oil sector contributed about five percent to output; despite its small size, this sector is a critical source of foreign exchange and government revenue.

The economy has changed significantly since the time of the revolution. Oil accounted for the majority of economic value added in 1978/79, as high prices gave the Shah’s government enormous oil revenues in the late 1970s; the agriculture, industry, and services sectors were minor by comparison.

Since the 1920s, the energy industry has been the most important element of Iran’s economy. How has the Islamic Republic developed the industry since 1979? Has the theocracy done anything different than the monarchy did?

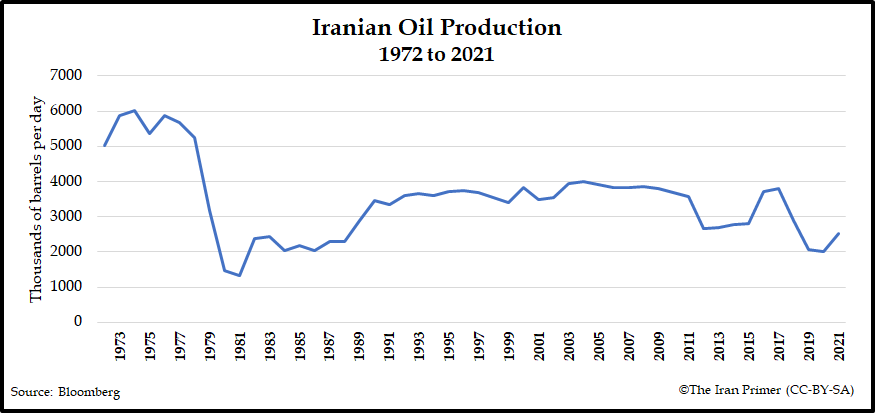

The Islamic Republic has struggled to develop the oil industry to its prerevolutionary stature. Prior to the reimposition of U.S. sanctions in 2018, Iran was producing about 3.8 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil, down from the pre-revolutionary high of 6 million bpd in 1974. Post-revolutionary oil production has never reached the volumes of the Shah era. The revolution and 1980-1988 war with Iraq dealt a devastating blow to the oil sector, both with the exodus of foreign workers and the destruction of facilities. In recent years, a combination of international sanctions and domestic political and ideological constraints have stymied efforts to attract investment and expand oil output.

Yet the Islamic Republic has diversified the energy sector in important ways over the decades, aided by new discoveries and spurred by both international assistance and pressure. With the discovery and development of the South Pars gas field and other sites, Iran has vastly expanded its natural gas production, from negligible volumes at the time of the revolution to more than 8 trillion cubic feet in 2019. More than 90 percent of natural gas production was consumed domestically for industrial, residential, commercial, and power purposes; gas was exported primarily to Iraq and Turkey, via pipelines.

Tehran has also expanded its production of higher-value petroleum and petrochemical products, such as gasoline, which reduced the need to import the fuel from abroad. From March to December 2021, petrochemical products accounted for more than 40 percent of all non-oil exports.

What challenges does the energy sector face in 2022?

Iran’s energy sector faces many barriers that keep it from realizing its full production and export potentials. U.S. sanctions have blocked foreign investment in the sector and restricted exports, reducing revenues that the state can invest back into the sector. Iranian companies lack the technical expertise of major international firms, so their absence has impeded growth.

The needs of the sector are staggering; in September 2021, the oil minister announced he intended to attract more than $100 billion in investment in the coming years, an amount that cannot be realized while sanctions are in place.

Sanctions are only part of the challenge. Even when U.S. and international sanctions were not in place, Iran had a troubled relationship with the international oil companies it was courting. Iran’s difficult business – rife with corruption, red tape, uncertainty, and controversial contract structures – has alienated potential investors.

Iran faces an additional complication in attracting foreign investment: With a global transition to renewable energy underway, big firms have significantly cut back on oil exploration and production in recent years, making long-term investments in Iran a tough sell.

What obstacles does the government face in selling Iran’s petroleum products abroad?

U.S. sanctions are the main impediment to Iran’s exports. Prior to reimposition of sanctions in May 2018, Iran had exported about 2.4 million bpd of crude oil; as of early 2022, it was exporting around 1.0 million bpd. Taking into account reduced exports, and the discounted pricing Iran offers on its oil, sanctions cost the government tens of billions of dollars in lost oil revenue every year.

If U.S. sanctions are lifted in 2022 – as part of a mutual return to compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal – Iran probably could return its exports to pre-2018 levels. But it may take as long as a year to ramp up oil production fully.

How has private industry evolved since 1979, when the early revolutionaries nationalized several parts of the economy?

State- and semi-state-owned entities are the dominant economic actors in post-revolutionary Iran. The private sector is a much smaller player, largely confined to small and medium-sized enterprises.

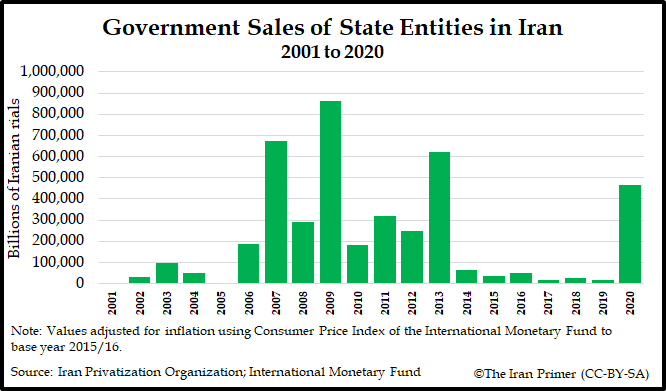

Over the past 30 years, successive Iranian presidents have launched privatization drives to shed assets that the government inherited from the Shah or seized following the revolution and during Iran-Iraq War. Yet, the result has been more akin to “pseudo-privatization.” Assets have been primarily sold to large conglomerates associated with religious and revolutionary foundations, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, pension funds, and other entities other than the “real” private sector. Therefore, the anticipated benefits of privatization—such as greater efficiency, competition, and tax base—have not materialized.

Over the past 30 years, successive Iranian presidents have launched privatization drives to shed assets that the government inherited from the Shah or seized following the revolution and during Iran-Iraq War. Yet, the result has been more akin to “pseudo-privatization.” Assets have been primarily sold to large conglomerates associated with religious and revolutionary foundations, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, pension funds, and other entities other than the “real” private sector. Therefore, the anticipated benefits of privatization—such as greater efficiency, competition, and tax base—have not materialized.

Of the post-revolutionary presidents, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) sold the most state assets, in rial terms, as the chart below shows. One of Ahmadinejad’s initiatives, called “Justice Shares,” involved distributing heavily discounted shares of state-run companies to more than 40 million low-income Iranians; the shares pay dividends and, as of 2020, can be traded on the stock exchange. Between 2003 and 2007, only five percent of shares sold by the government went to private firms, according to one study. A separate Iranian study, published in 2010, assessed that the private sector received 13.5 percent of shares issued since Ahmadinejad took office.

What percentage of Iran’s industries and financial sectors are owned by the government? And what percentage by private industries or individuals? And how has that changed since 1979?

There are no reliable statistics on the breakdown between state, semi-state, and private entities in Iran, although academics and business organizations have attempted to approximate the data. A 2019 study examined the top 300 firms traded on the Tehran Stock Exchange. Private sector entities had controlling shares of firms in four sectors (real estate, automotive, rubber and plastic, and banking and securities) and minority shares of firms in two sectors (cement and insurance). All other major economic sectors were dominated by state or semi-state institutions.

Which countries are Iran’s most important trading partners? How have trading partners changed since 1979? Why?

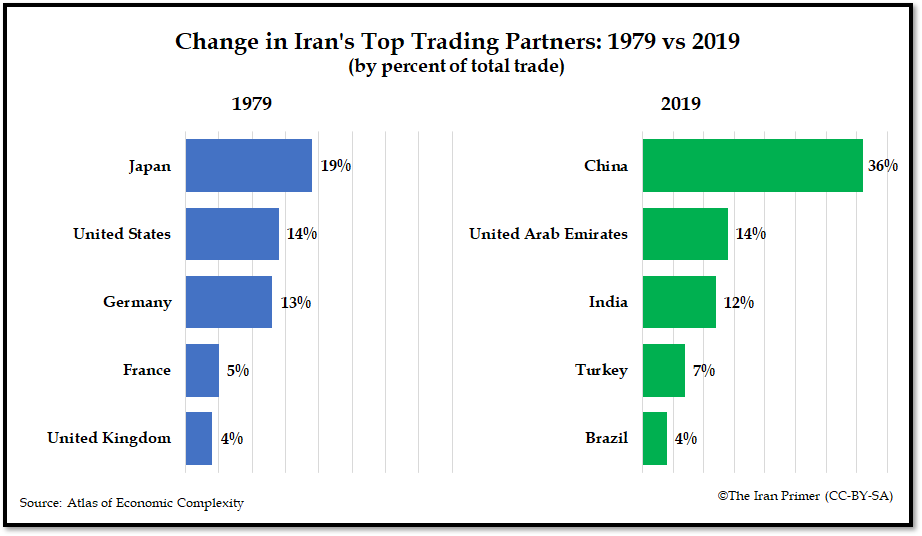

Iran’s largest and most important trading partner is China. In 2022, it was the only country purchasing significant volumes of crude oil exports. It also accounted for 30 percent of non-oil trade (between March and November 2021). The United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Turkey are other key partners, demonstrating the importance of regional trade to Iran’s strategy to weather U.S. sanctions. Trade with India and Brazil – two other important partners – has declined since the reimposition of sanctions in 2018.

In 1979, Iran’s trading partners looked quite different. The top five trading partners, as the chart below shows, were all industrial democracies, led by Japan and the United States. The shift can be attributed to politics and market forces. Over the decades, Iran shifted away from the West and sanctions took hold; meanwhile, soaring economic growth in the developing world created new markets for Iranian products and sources for imports.

The United States, European powers, and the United Nations have imposed sanctions on Iran in fluctuating waves since 1979. How have sanctions impacted the economy? What sectors of the economy have been most affected?

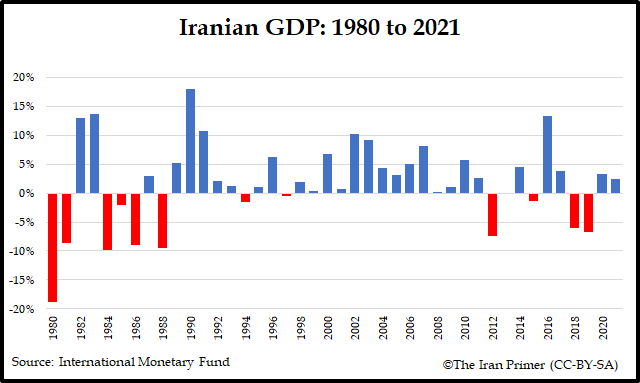

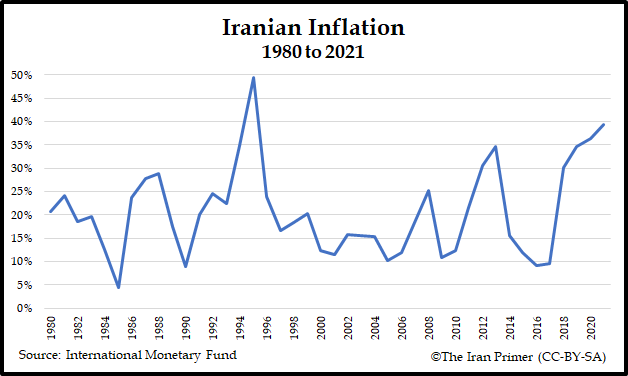

Multilateral sanctions have directly or indirectly affected all aspects of the Iranian economy, especially during the two most-recent waves of sanctions (2010-13 and 2018-present). Trade and financial sanctions have disrupted Iran’s connections to global markets, sending the economy into recession, driving inflation higher, and weakening the currency.

Sanctions have hurt businesses by raising the cost of imports, limiting destinations for exports, and reducing opportunities for domestic and foreign investment. The disruptions to both personal and business finances have led to more Iranians leaving the workforce and an increase in the number of Iranians in poverty. These restrictions exacerbated existing weaknesses and inefficiencies in the Iranian state, including a poor business climate and endemic corruption. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the sanctions-related pressures.

Sanctions have hurt businesses by raising the cost of imports, limiting destinations for exports, and reducing opportunities for domestic and foreign investment. The disruptions to both personal and business finances have led to more Iranians leaving the workforce and an increase in the number of Iranians in poverty. These restrictions exacerbated existing weaknesses and inefficiencies in the Iranian state, including a poor business climate and endemic corruption. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the sanctions-related pressures.

The impact on the oil sector has been the most severe, given the global nature of the oil market and the dominance of the U.S. dollar. While oil’s share of the economy is relatively small, it is a key source of revenue and hard currency. Sanctions have also disrupted Iran’s non-oil export industries through direct sanctions and the severing of international banking connections.

The services sector has been relatively insulated, given its more domestic focus. For example, at the onset of U.S. sanctions in 2018/19, the oil sector shrank more than 18 percent and the industrial sector by nearly 4 percent, but the services sector declined by just 0.1 percent.

The services sector has been relatively insulated, given its more domestic focus. For example, at the onset of U.S. sanctions in 2018/19, the oil sector shrank more than 18 percent and the industrial sector by nearly 4 percent, but the services sector declined by just 0.1 percent.

How has Iran adapted to circumvent the limitations on trade?

Iran has developed several strategies to bypass U.S. sanctions or mitigate their effects, with varying degrees of success. U.S. sanctions imposed under the Trump administration targeted all major sectors of the Iranian economy. They have been most effective in curtailing oil exports because oil is traded on a global market that relies on an intricate web of shippers, traders, insurers, ports, and refiners which are vulnerable to government pressure. Iran has attempted to frustrate U.S. efforts by concealing tanker movements and selling oil at a discount, to encourage sanctions busting.

For non-oil trade, Tehran has focused intently on its neighbors. Regional trade is far more difficult to track and disrupt, as exchanges can take place directly in small quantities in local currencies. For both oil and non-oil trade, Iran has experimented with using barter arrangements as well, to avoid the complexity and risks of moving money. Finally, Iran has sought to reduce reliance on foreign imports as part of its “resistance economy” strategy.

For non-oil trade, Tehran has focused intently on its neighbors. Regional trade is far more difficult to track and disrupt, as exchanges can take place directly in small quantities in local currencies. For both oil and non-oil trade, Iran has experimented with using barter arrangements as well, to avoid the complexity and risks of moving money. Finally, Iran has sought to reduce reliance on foreign imports as part of its “resistance economy” strategy.

Iran’s revolutionaries set up a welfare state to protect what they called the “oppressed.” How has Iran implemented its vision of social justice? To what extent has Iran succeeded in bettering the life of the working and lower classes?

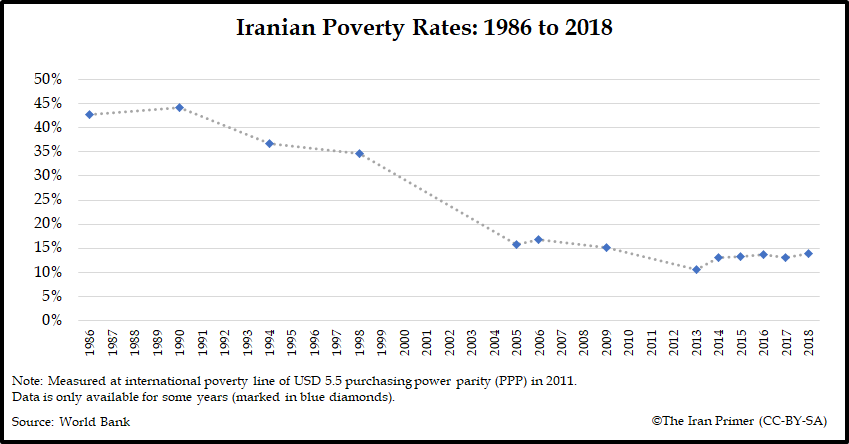

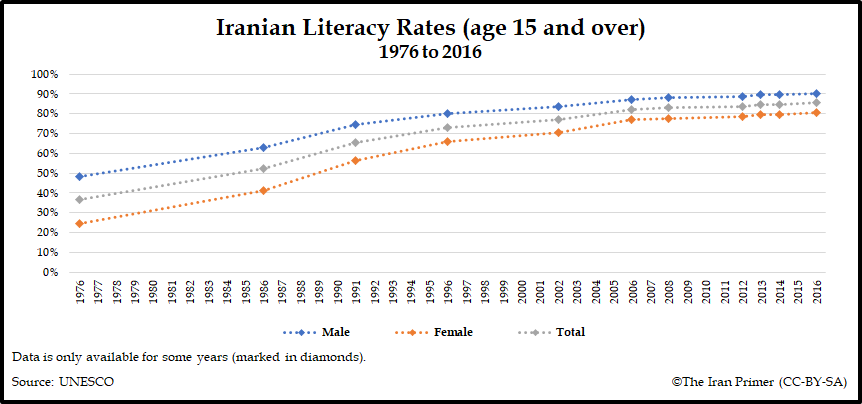

The Islamic Republic has made significant progress in shrinking the welfare gaps between urban and rural populations and between men and women, as well as reducing poverty rates. In the revolution’s aftermath, the government established new institutions and initiatives to expand access to healthcare, education, and basic infrastructure, especially to rural and poorer communities. In aggregate, these efforts contributed to a sharp reduction in poverty starting in the early 1990s that led to a vast expansion of the middle class and a widespread improvement in literacy.

But since 2018, with the combination of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign, and the COVID-19 pandemic, the poverty rate has slightly increased.

Tehran has also directly or indirectly subsidized oil, electricity, gas, bread, wheat, water, and other items to varying degrees for decades. Yet these subsidies have proven enormously costly, and the government has tried in recent years to shift support measures from artificially suppressing prices to offering direct cash handouts. Reforming subsidies has proven highly controversial, as leaders have struggled to balance state finances with offering social support to the most vulnerable members of society, fulfilling a key tenet of the revolution.