In August, Iran began shipping badly needed fuel to Lebanon through Hezbollah, the Lebanese political movement and militia. The move demonstrated Tehran’s unwavering support for the group and defiance of U.S. sanctions. Hezbollah used the shipments to bolster its image amid Lebanon’s economic crisis.

Iran dispatched three tankers to Syria. As of September 29, two ships had arrived in Syria, where the diesel was transferred onto trucks bound for Lebanon. A third tanker carrying gasoline was on its way, and a fourth was expected to depart Iran in winter 2021. Hezbollah had Iran bring the fuel to Syria for overland transfer to Lebanon to avoid embarrassing the Lebanese government and to mitigate the risk of U.S. sanctions.

“Certainly we cannot see the suffering of the Lebanese people,” Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Saeed Khatibzadeh said on August 23. Tehran said that it sold the fuel to a Lebanese businessman. The first ship reportedly carried up to 13.2 million gallons of fuel, enough to meet Lebanon’s needs for just two or three days. But the modest shipments carried a far more substantial symbolic weight.

“Certainly we cannot see the suffering of the Lebanese people,” Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Saeed Khatibzadeh said on August 23. Tehran said that it sold the fuel to a Lebanese businessman. The first ship reportedly carried up to 13.2 million gallons of fuel, enough to meet Lebanon’s needs for just two or three days. But the modest shipments carried a far more substantial symbolic weight.

First, the shipments showed that Iran remains deeply committed to Hezbollah. The Shiite movement was Iran’s first proxy in the Middle East. It started as a militia in the early 1980s, with military and financial support from Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. It evolved into the region’s most powerful militia and a major player in Lebanese politics.

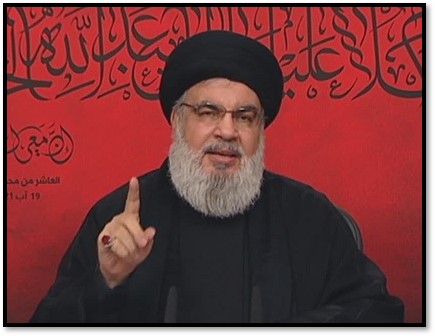

“Hezbollah’s budget, everything it eats and drinks, its weapons and rockets, comes from the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah said in 2016. In 2018, the Treasury Department estimated that Tehran provided the group with more than $700 million annually.

Nasrallah welcomed hardliner Ebrahim Raisi's victory in Iran's 2021 presidential election. “Your victory has renewed the hopes of the Iranian people and the people of the region who see you as a shield and a strong supporter… for the resistance against aggressors,” he said on June 20.

Second, the shipments highlighted Hezbollah’s ability to provide services where the government has failed. Lebanon has suffered an acute energy crisis since June 2021, when interim Prime Minister Hassan Diab reduced oil subsidies amid a broader economic collapse. Fuel prices soared. The Lebanese government was only able to provide electricity for a couple of hours each day. Many people and businesses were reliant on diesel fuel to power generators.

Nasrallah pledged to donate some of the fuel to government-run hospitals, orphanages, and the Lebanese Red Cross. He vowed to sell some below the market rate to private hospitals, medicine factories and bakeries. Nasrallah also said that fuel would be distributed to gas stations connected to the group. Hezbollah is “not looking to make a business out of this but wants to help ease the people's hardships,” he said on September 13.

Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati said that the government had not approved the shipments. “Frankly, I am sad, because this [violates] the sovereignty of Lebanon,” he said in an interview on CNN on September 17. The first convoy of trucks passed through an unofficial border crossing in Qusayr without being inspected.

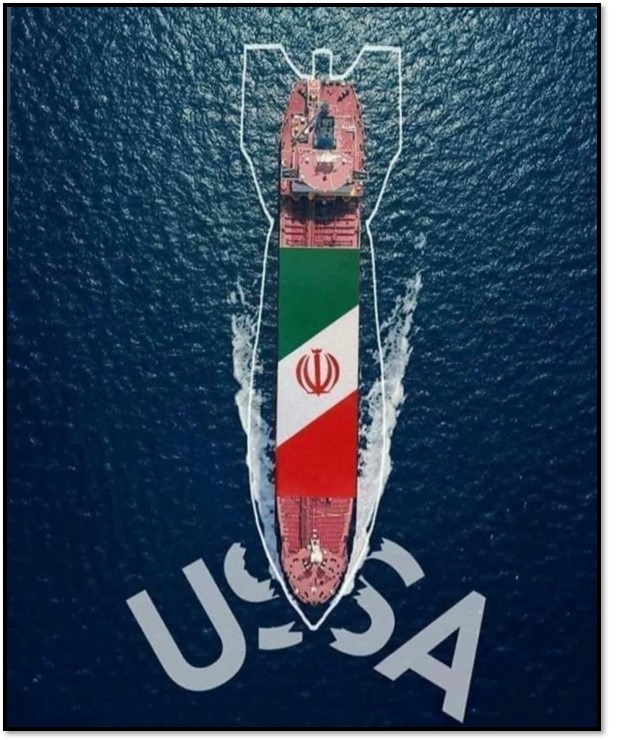

Third, the shipments were an act of defiance toward the United States by Iran and its allies. Hezbollah claimed credit for breaking what it considered an “American siege” on the country. The group had blamed the United States for Lebanon’s economic problems.

On social media, pro-Iran and pro-Hezbollah users shared a graphic depicting an Iranian tanker as a missile breaking through the letters "USA" superimposed on the water.

The fuel transfers appeared to violate U.S. sanctions since most of the parties involved were already sanctioned:

- Iran: In 2018, the United States reimposed sanctions on key sectors of Iran’s economy, including the oil industry, after then-President Donald Trump withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal.

- Hezbollah: In 1995, the United States sanctioned Hezbollah and Secretary General Nasrallah for disrupting the Middle East peace process. It designated Hezbollah a Foreign Terrorist Organization in 1997 and a Specially Designated Global Terrorist in 2001.

- Amana: In 2020, the United States sanctioned Amana fuel company for its connections to Hezbollah. Amana was the company charged with distributing the Iranian fuel in 2021.

- Syria: In 2004, the United States sanctioned Syria for several reasons, including supporting terrorism, occupying Lebanon and pursuing weapons of mass destruction. Since 2011, the United States has imposed additional sanctions for Syria’s violent crackdown on anti-government demonstrators.

The first convoy of 60 trucks that crossed in Lebanon received a hero’s welcome. On September 16, Hezbollah supporters threw rice and rose petals onto the road, fired weapons into the air, passed out sweets and played celebratory music. “Thank you Iran. Thank you Assad's Syria,” read a banner in the northern village of al Ain.

U.S. Response

After Nasrallah announced the first shipment of Iranian fuel, the United States was mum about a response. “I don’t think anyone is going to fall on their sword if someone’s able to get fuel into hospitals that need it,” the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon, Dorothy Shea, told Al Arabiya English on August 19. “But I think the Lebanese people deserve importers of fuel to distribute it equitably. And I ask you, can you count on Hezbollah to do that?”

Ambassador Shea said that the United States was working on alternative energy sources for Lebanon. “We’ve been talking to the governments of Egypt, Jordan, the government here [Lebanon], the World Bank. We’re trying to get real, sustainable solutions for Lebanon’s fuel and energy needs.”

On September 8, energy ministers from Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria agreed to work together on resuming shipments of Egyptian gas to Lebanon.

The United States is the largest provider of humanitarian aid to Lebanon. On August 4, the Biden administration announced a $100 million aid package to Lebanon.

The following is a timeline of Iran’s fuel shipments to Lebanon.

2021

June 25: Interim Lebanese Prime Minister Hassan Diab signed a decree financing fuel imports above the official exchange rate. The move increased gasoline and fuel prices by 35 percent, incentivizing distributors to hoard their supply to sell at a higher price later.

August 19: Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah blamed the United States for Lebanon’s current energy crisis and promised an incoming shipment of Iranian fuel to Lebanon.

August 22: The Lebanese government raised fuel prices by 66 percent to curb the fuel shortage.

September 12: The first Hezbollah-commissioned Iranian tanker arrived at the Syrian port of Baniyas. The fuel was transferred to tanker trucks.

This morning's satellite imagery captured by @planet confirms that the Iran-flagged handysize tanker FOREST (9283760) is currently discharging her cargo of fuel at one of the petroleum product SBM stations of the Baniyas refinery in Syria. This fuel is earmarked for Lebanon. pic.twitter.com/1gUBzI9bNe

— TankerTrackers.com, Inc. (@TankerTrackers) September 25, 2021

September 16: A convoy of 60 trucks, each carrying 13,000 gallons of oil, arrived in Lebanon via the informal Qusayr border crossing in Syria. Nasrallah claimed that Hezbollah had “broken the American siege.”

September 17: A second convoy of 60 tanker trucks arrived in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley from Syria. The trucks’ destination was Baalbek, where the Hezbollah-linked oil distribution company Amana was supposed to distribute the oil freely to hospitals, orphanages, local governments, the Lebanese Red Cross, and others.

In an interview with CNN, Prime Minister Najib Mikati said that the shipments constituted a violation of Lebanese sovereignty. Mikati added that he did not want to discuss the issue further “because we are trying to solve this in a very calm way.”

September 19: A third tanker departed Iran for Syria.

September 23: The second Hezbollah-commissioned Iranian tanker arrived at the Syrian port of Baniyas.

September 26: Hadi Beiginejad, a member of the Iranian parliament’s energy committee, said that fuel shipments to Lebanon were “definitely not for free” without specifying a payment method.

Brett Cohen, a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson Center, and Garrett Nada, managing editor of The Iran Primer, contributed to this report.