The coronavirus outbreak has created new challenges and exacerbated old ones for Iran’s economy. The outbreak of COVID-19, first announced on February 19, forced businesses nationwide to close just before Nowruz, the Persian New Year, on March 20. Trade slowed due to border closures. By mid-April, the government admitted that four million people—in a labor force of 27 million—could lose their jobs if the shutdown was prolonged or the government didn’t intervene. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its original estimate—of zero growth in 2020—to project that the economy would shrink by up to six percent. Iran's parliamentary think tank projected that the economy could shrink by up to 11 percent.

In a report in late March, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Finance identified eight economic challenges in the new Iranian year, most related to the pandemic:

- Shrinking foreign exchange reserves

- Lower oil and petrochemical prices

- Reduced tax revenues due to business losses

- A deepening recession in the services sector

- Less global demand for mineral products and lower income from metal sales

- Reduced consumer demand for goods and services

- Increased government spending to deal with the health crisis

- A larger budget deficit

On April 3, 50 economists provided an even bleaker outlook in an open letter to President Hassan Rouhani. They also predicted increased unemployment, higher inflation, more poverty and unrest in some low-income areas. The virus hit three months after widespread protests in November 2019 sparked by a sudden hike in gas prices.

Tehran already faced a daunting combination of external pressures and internal issues. Iran was already isolated after the United States reimposed sanctions in 2018 and six months later cancelled sanctions waivers for third countries who bought Iranian oil. Its oil sales were slashed in 2019. Then oil prices crashed in March 2020, partly because of the global pandemic. The rapid spread of the virus to all 31 Iranian provinces also hit sectors of the economy insulated from sanctions, such as tourism, domestic trade and non-oil exports. Yet for all the new challenges, Iran’s economy was not on the verge of collapse in April 2020.

Government Response

The government announced several initiatives to cushion the impact of COVID-19. On March 29, the government approved $6.3 billion stimulus package that included funding for the health ministry, increased unemployment insurance, and aid to businesses, workers and families. On April 6, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei approved Rouhani’s request to withdraw 1 billion euros ($1.09 million) from the National Development Fund to supplement the health ministry and unemployment insurance.

President Hassan Rouhani spoke at a cabinet meeting on April 15.

But Iran’s stimulus package was less than two percent of its GDP of $485 billion in 2019—far less than any of the other oil-producing countries in the Gulf. The Islamic Republic has the region’s second largest economy, but as of late March, its neighbors across the Persian Gulf planned to spend more money—nearly 30 percent of GDP in Bahrain and Oman, more than 10 percent in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, and more than four percent in Saudi Arabia, according to Fitch Ratings. (As of April 27, the U.S. stimulus package was 11 percent of GDP; Japan’s stimulus package was 21 percent of GDP.)

Iran’s stimulus package was not large enough to sustain the economy for months, “too little too late,” according to Ali Dadpay, a professor of finance at the University of Dallas. Rouhani conceded that the economy had to be reopened to ensure Iranians could work or basic services could collapse. In a closed-door meeting on March 13, military leaders reportedly called for continued quarantines, similar to those enforced in China and Italy, to halt the spread of COVID-19. But Rouhani refused on grounds that the government was unable to support millions of people forced to stay home, according to The New York Times.

On April 5, Rouhani announced plans to gradually reopen the country, citing a decrease in new COVID-19 cases. “With the protection of health as a priority and with all the necessary health protocols, we must adopt measures to move the wheel of the economy,” Rouhani said at a cabinet meeting. Low-risk economic activities were allowed to resume in most provinces on April 11 and in Tehran on April 18. The ban on travel between cities ended on April 12 and Iranians were allowed to travel between provinces again on April 20.

Limited Outside Help

Iran acknowledged that it needed foreign assistance to cope with the economic repercussions. On March 6, the governor of the Central Bank of Iran requested an emergency $5 billion loan from the IMF. The request was unprecedented. Iran last received IMF assistance in the early 1960s during the monarchy. But in 2020, the Trump Administration said it would block Tehran’s request. Iran’s Central Bank, which is currently under sanction, “has been a key actor in financing terrorism across the region and we have no confidence that funds would be used to fight the coronavirus,” a U.S. Treasury official told CNN.

Iran still had more than $500 million in its so-called reserve tranche at the IMF; these are funds that it contributed and could tap without a service fee or facing conditions from other IMF members. It also had on-demand access to some $1.6 billion in “Special Drawing Rights” (SDR) at the IMF. The SDR is an international reserve asset that supplements the official reserves of member countries. It is allocated to member countries based on their IMF quotas and relative standing in the world economy. Members can exchange SDRs for useable currencies from other members.

To provide short-term relief, more than 30 countries sent medical supplies to Tehran. The European Union pledged to send 20 million euros ($21.5 million) in materiel and 5 million euros ($5.4 million) in financial aid. The following outlines the impact of the coronavirus on Iran’s economy.

Related Material: Dozens of Countries Send COVID-19 Aid to Iran

Unemployment

Unemployment rose because of COVID-19. By mid-April, 3.3 million employees had been dismissed, furloughed or had their wages reduced, according to government spokesperson Ali Rabiei. Another four million self-employed workers were negatively impacted. Some 820,000 people filed for unemployment between mid-March and mid-May, according to a Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare official.

The government acknowledged the long-term potential impact. More than four million people could lose their jobs due to a prolonged shutdown, Rabiei warned in an op-ed. In late April, Parliament’s research arm warned that 6.43 million Iranians could lose their jobs.

Many of the businesses that took the worst hits were part of the service sector, which employs 12 million people or nearly half of the labor force. Historically, the service sector also accounted for about half of Iran’s GDP, so decreased tax revenues could put additional pressure on the budget.

A national survey reflected the sweeping impact. Conducted in mid-April by the Iranian Students Polling Agency (ISPA), it showed:

- 50.7 percent of respondents said their income had been reduced

- 42 percent said their businesses were closed

- 13.5 percent said their lost their jobs

- 26.3 percent said their economic situation had not changed

- 0.6 percent said their situation had improved

- 1.6 percent also mentioned other options

During the pandemic, Iran did not have the financial resources to support the newly unemployed, which was already high before the virus hit. Official unemployment averaged 10.6 percent during the last quarter of the Iranian year ending on March 20. Youth unemployment was much higher at 26 percent. The government tried to incentivize employers to retain workers by promising four million low-interest loans for businesses that did not lay off employees. But business loans offered little protection to the some six million workers – or about a quarter of the labor force – employed in the informal economy or as day laborers.

Rising Inflation

The pandemic hit at a particularly hard time economically. Inflation during the Iranian year 1398 – March 2019 to March 2020 – hit 41.2 percent, the highest in some 25 years. The cost of living has skyrocketed since the United States reimposed sanctions in November 2018. Between mid-2018 and mid-2019, the cost of red meat and poultry rose 57 percent, dairy and eggs by 37 percent, and vegetables by 47 percent. The stress on household budgets has reportedly pushed as many as 1.6 million Iranians below the poverty line since late 2018. In April 2020, the IMF projected inflation would be at least 34 percent in 2020. Inflation could be exacerbated if the government prints money to back the COVID-19 stimulus package.

Monthly Inflation Rate (Percent)

Source: tradingeconomics.com

The pandemic also accelerated depreciation of the rial, which had already plummeted in value as the U.S. reimposed sanctions in 2018. Just before the first cases of coronavirus were reported in mid-February, the free market exchange rate was 144,000 rials to the U.S. dollar. Two months later, it was around 160,000 rials to the dollar, the weakest since September 2018.

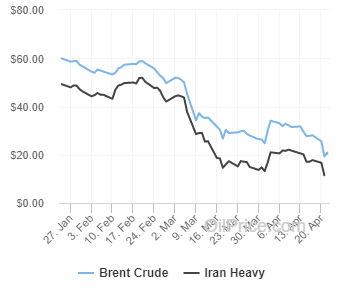

Dwindling Oil Revenues

Already hard hit by U.S. sanctions, Iran faced a stunning decline in the price of oil – a major source of revenue – as an unexpected byproduct of the coronavirus pandemic. The first global price shock came in early March, as an increasing number of governments ordered people to stay home. The demand for fuel sharply declined with less factories online, planes in the air and cars on roads. The trend was worldwide. By April 1, the price of Iran’s heavy crude fell to below $14 per barrel — down from $44 or more per barrel in February.

On April 12, OPEC and its partners, including Russia, finalized a deal to cut oil production by 9.7 million barrels by July. It had the potential to push prices back up somewhat.

But a second price shock came in late April. Prices fell due to the shortage of storage space for excess supply. On April 20, the price of West Texas Intermediate, the benchmark for U.S. oil, hit negative $37.63, the lowest price in history. Global prices followed. On April 21, Iranian crude was selling for $11.51.

For updated prices, see OilPrice.com

But Iran has been forced to sell oil at an even cheaper price and offer incentives to buyers because of U.S. sanctions reimposed in November 2018. Revenue shortfalls will be problematic for Iran and other exporters – including its regional rival Saudi Arabia – with budgets based on much higher prices.

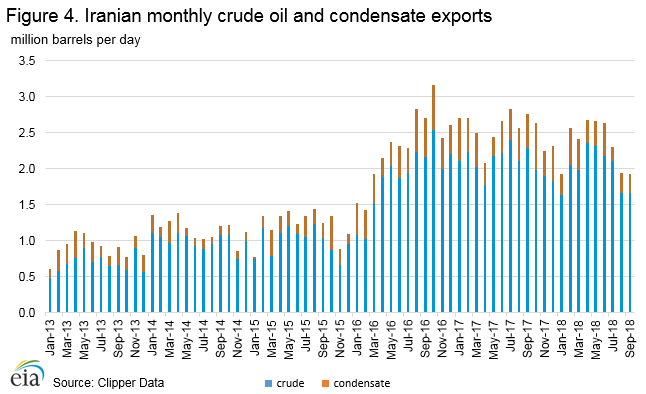

The budget for the Iranian year, which started on March 20, was based on sales of 1 million barrels per day (bpd) at an average of $50 per barrel. The estimate was optimistic even before the coronavirus outbreak. In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected that Iran’s exports will average only 500,000 bpd in 2020 – half of what Tehran needs. In March, Iran reportedly exported as little as 140,000 bpd. In April, it reportedly exported as little as 70,000 bpd.

Iran’s foreign currency reserves, which it needs to import consumer goods, machinery and industrial materiel, will be endangered by falling oil revenues. Before the pandemic hit, the IMF had estimated that Iran’s foreign currency reserves would fall from $86 billion to $70 billion in 2020. On May 10, parliament passed a law that would impose a fine on individuals trying to take foreign currency out of the country. The legislation reflected economic fears and the need for foreign exchange.

The Islamic Republic has become increasingly dependent on imports of essentials such as wheat, sugar, corn, rice, red meat, soybeans, and paper. Imports of essentials were up 17 percent in the last Iranian year that ended in March 2020. “Persistently low prices will exacerbate the imbalance between imports and exports and force Iran to draw more on its foreign currency reserves, giving it less of a cushion moving forward,” said Henry Rome, a senior analyst at the Eurasia Group. The slash in prices could also deepen Iran’s budget deficit, which is projected to be 9.9 percent of GDP in 2020, up from 5.7 percent in 2019, according to the IMF.

Iranian officials have tried to downplay the impact of historically low oil prices. On April 21, First Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri announced that the budget had been adjusted to assume zero oil revenue. In Iran’s budget for 2019, oil revenues accounted for 29 percent of budget revenues. For 2020, oil revenues were projected to account for nine percent of the budget. “The crises and the sanctions imposed by the United States of America have prepared us for running the country under the current circumstances,” he said.

Iran’s oil exports were already severely curtailed by U.S. sanctions, which were re-imposed by the Trump Administration in November 2018. Iran’s oil exports have dropped from a high of 2.54 million barrels per day in October 2016. By April 2019, Iran exported about 1 million bpd. In May 2019, Washington intensified its “maximum pressure” campaign to get Iran to negotiate an expanded nuclear deal. It also cancelled sanctions waivers for key countries that bought Iranian oil, which further crimped oil sales.

Testing Resilience

Iran’s economy has survived war, natural disasters, sanctions, chronic mismanagement and corruption for four decades. As the country began to reopen in April 2020, workers returned to factories and workshops, and shoppers found well-stocked shelves.

A woman filled her cart in a well-stocked aisle in Tehran on April 2.

At the same time, the research arm of parliament warned that Iran could face a shortage of essential goods this year. Iran’s imports of wheat, sugar, corn, rice, red meat, soybeans, paper and other basic goods increased 17 percent in the year that ended in March 2020.

Iran may also rely on two sectors – industries and agriculture – to sustain the economy. Neither was significantly impacted during the first two months of the pandemic. In 2019, industries accounted for 32 percent of jobs and agriculture for 17 percent of jobs, according to the World Bank.

During a cabinet meeting on April 15, 2020, President Rouhani presented an optimistic view of the year ahead, despite the pandemic. Agricultural production was projected to grow by 3.5 percent or more and the non-oil sectors to continue growing. The non-oil parts grew 1.3 percent between March 2019 and December 2019, according to the Central Bank.

But the IMF’s outlook for 2020 differed starkly. It projected GDP from non-oil sectors to contract by six percent in 2020.

Timeline of Government Announcements and Economic Intervention

March 4: The Money and Credit Council, the policy-making body of the Central Bank, announced that businesses would be exempt from loan repayments for three months from mid-February through mid-May 21.

March 6: Central Bank Governor Abdolnasser Hemmati requested a $5 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF had said it would support countries impacted by COVID-19 via its Rapid Financial Instrument. Iran last received IMF assistance during the monarchy in the early 1960s.

March 8: The National Tax Administration offered waivers from penalties for late tax payments from February 20 through March 19 on condition businesses paid by June 20.

March 9: To curtail bank visits and the circulation of paper money, the Central Bank increased the amount Iranians could transfer from their debit accounts from 30 million rials ($194) to 100 million rials ($645 at the free market rate).

March 11: The Central Bank governor said banks would extend low-interest loans to four million business owners impacted by the virus. “Interest is 12 percent, but the government will pay eight percent and the borrowers four percent,” he told reporters. The Central Bank issued a list of the types of business eligible for government assistance:

- food distributors, such as restaurants, reception halls, coffee shops, buffets, fast foods, etc.

- businesses active in tourism and the hospitality sector, such as hotels, guesthouses, etc.

- air, road, rail and sea transportation companies

- apparel manufacturers and distributors

- leather and footwear

- confectionaries and shops selling dried fruits

- gyms and recreational centers

- educational and cultural centers

- craftsmen and handicraft shops

Hemmati said businesses eligible for government assistance will be given a three-month grace period to repay debts.

March 11: Iran’s top car manufacturer, Iran Khodro, announced that it would start lowering output at its plants and halt production completely before Nowruz on March 20 because of the pandemic. The auto manufacturing sector had already seen a significant decline. It produced 25 percent fewer cars in 2019, according to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers.

March 12: Rouhani ordered financial aid—from $13 to $130—to seven million people in need. About half of the payouts were to be low-interest loans.

In a tweet, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif urged the IMF to help Iran by providing financial assistance.

IMF's @KGeorgieva has stated that countries affected by #COVID19 will be supported via Rapid Financial Instrument. Our Central Bank requested access to this facility immediately.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) March 12, 2020

IMF/IMF Board should adhere to Fund's mandate, stand on right side of history & act responsibly.

March 13: The government ran spring fairs online to help some 100 businesses sell their goods ahead of Nowruz after annual events were cancelled because of the pandemic.

March 15: In a televised address, Rouhani announced sweeping measures to support families and businesses impacted by the pandemic. The package allowed employees to defer payments for health insurance, taxes, and utility bill payments. It provided a new cash subsidy for three million of Iran’s poor on March 17. But the president ruled out plans for a lockdown. “There is no quarantine. Not today, not during the New Year holidays, not after it nor before it. Everyone can conduct their business” he said.

The Central Bank released a list of businesses—involved in food, apparel, travel, education, and recreation—eligible to receive credit from banks because they had been directly impacted by the pandemic.

The Plan and Budget Organization said that seasonal workers, vendors, taxi drivers and restaurant staff who lost their jobs would be eligible for assistance—in the form of credits for the purchase of goods—if they registered with the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare.

Tehran City Councilor Zahra Nejad-Bahram said that vendors in the capital could receive financial support from the Mostazafan Foundation, the largest charitable organization as well as the second largest commercial enterprise in Iran. The foundation said that it would not collect rent for its commercial real estate properties for two months between mid-February and mid-April.

Donya-e-Eqtesad, a financial newspaper, published a chart about the decline in demand in 20 sectors based on government data. Businesses dependent on foot traffic and gathering large groups of people, such as restaurants, gyms and event spaces, were hit especially hard.

Iran #COVID19 latest:

— Ali Vaez (@AliVaez) March 15, 2020

* 1209 new cases, nearly 14000 total

* 724 confirmed fatalities

* Budget official: 3m Iranians to receive cash transfers; 4m more eligible for low-interest loans

* @deghtesad publishes chart showing major impact on domestic business (translation below). pic.twitter.com/lp9731SAbE

March 16: The Central Bank approved $250 million in emergency funds for importing drugs and medical supplies.

March 19: The government approved a revised budget that increased spending by 15 percent compared with the proposal submitted by Rouhani. The budget included an increase in civil servant salaries as well as a 25 percent increase in spending on development projects. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ budget was increased by more than 60 percent, well above the rate of inflation. Funding for the Basij militia increased by about one-third.

Related Material: Iran’s Crisis Budget

March 24: Rouhani said that about half of all government workers were staying home to help curtail the spread of the virus. First Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri vowed that small business owners would be compensated for losses during the coronavirus crisis.

March 26: The government extended about $47 million in low-interest loans—at 12 percent for two years—to businesses impacted by the health crisis if they did not lay off employees. It also sought to withdraw 1 billion euros from the National Development Fund, which required the approval of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. He approved it on April 6.

March 28-29: Rouhani said Iran would use 20 percent of its new budget, or $6.3 billion, to combat the COVID-19 outbreak. On the following day, the government approved the stimulus package. It included funding for the health ministry, the unemployment insurance fund, and aid to businesses, unemployed workers and poor families.

April 1: In a cabinet meeting, Rouhani claimed that Iran was successfully containing the outbreak and coping economically. “I would like to tell our dear people that despite sanctions, hardships and problems, we set aside about $10 billion to remove barriers to businesses that were in trouble. Part of that will be in loans, part in grants and part in packages paid to families and people in need,” he said.

April 5: Rouhani announced that low-risk economic activities would resume on April 11 in most provinces and on April 18 in Tehran. He did not specify which activities would be permitted. High-risk activities—including school and university classes as well as social, cultural, sports and religious events—would be suspended until at least April 18.

April 6: Rouhani announced that nearly all of the 23 million households already receiving government subsidies would get another $61 in financial aid. He later clarified that the aid would be in the form of an interest-free loan. The three million neediest citizens would receive an additional $12 to $37. Another four million low-income families could apply for low-interest loans of $124. The government also provided $792 million to the Health Ministry for supplies and to research firms to study the coronavirus. The government also provided more than $300 million to the unemployment insurance fund.

April 7: Parliament rejected a motion calling for a one-month nationwide lockdown. Proponents argued that it was more important to save lives than to restart the economy before the virus was fully contained.

April 11: Government offices outside of Tehran reopened, but about a third of employees worked from home.

April 15: Rouhani said the government would sell about 10 percent of its holdings in the Social Security Investment Company, a massive state-managed entity, to raise funds to pay for COVID-19 containment efforts.

April 16: Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance Abbas Saleh urged the government to aid the culture, art and media sectors, which reported losses of $65 million due to the outbreak.

April 20: Shopping malls, bazaars and businesses deemed “medium-risk” reopened across Iran.

April 24: The Ministry of Industry, Mining and Trade launched the country’s largest aluminum factory. Rouhani inaugurated the nearly 500-acre complex via video conference. The facility was expected to boost aluminum production by more than 60 percent and employ 1,500 people directly as well as 5,000 indirectly. Metals have historically been an important source of export revenue. In May 2019, the United States sanctioned the iron, steel, aluminum and copper sectors.

April 27: Government spokesman Ali Rabiei announced that all of Iran’s borders, except for the one with Turkmenistan, had been reopened to trade. Rabiei said that goods and businesspeople could traverse borders and that travelers would eventually be allowed to with permission from the Health Ministry. But not every border crossing was open to all trade yet. For example, Turkey and Iran only resumed regular rail trade. The northern border with Iraq was open while negotiations on southern checkpoints were ongoing.

April 29: The president of the Iranian Hoteliers Association, Jamshid Hamzezadeh, said that the tourism industry lost some $330 million due to the COVID-19 outbreak from February to April 19.

May: Iran’s stock market boom, including daily gains of 5 percent, made analysts worry that the potential impact of a crash. The Tehran Stock Exchange had seen gains of 225 percent in the last year. The government had been selling assets on the market to raise money.

May 10: Parliament passed a law that would impose a fine on individuals trying to take foreign currency out of the country. The fine could be two to four times the equivalent amount of rials. The legislation reflected economic fears and the need for foreign exchange.

May 14: Kpler, a data intelligence company that tracks oil flows, estimated that Iran exported between 70,000 to 200,000 bpd in April, the lowest in decades either way. The decline was largely due to a decline in Chinese purchases.

May 15: The Ministry of Health had received more than $995 million (at the official exchange rate of 42,000 rials to the dollar) to combat the COVID-19 outbreak, according to state-controlled media.

May 17: The Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare announced that a total of $75 million had been deposited into the Social Security Organization’s Unemployment Insurance Fund. A ministry official reported that some 820,930 people had filed for unemployment between mid-March and mid-May.