2017 was tumultuous for many Middle East countries, but less for Iran than in previous years. Tehran encountered few existential political or security challenges, whereas Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Libya faced basic questions about their long-term viability. Iran capitalized on the region’s chaos to become more powerful than at any point since the 1979 revolution.

In 2017, the Islamic Republic reelected President Hassan Rouhani. Its economy saw modest growth from sanctions relief after the 2015 nuclear deal. It largely maintained control of its borders and internal security, except for one bloody attack by ISIS and some small border skirmishes with militants. By the end of 2017, Iran and its allies commanded significant influence in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Lebanon. The following is a review of major developments in 2017.

Domestic Politics

Rafsanjani’s Death

The first major event of 2017 was the death of former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. The 82-year-old cleric died of a heart attack on January 8. He had held top positions in the Islamic Republic since the 1979 revolution. He was speaker of parliament during the tough war years in the 1980s and president for two terms from 1989 to 1997. He was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, a panel of more than 80 clerics and scholars who oversee the supreme leader, from 2007 to 2011. And he was chief of the Expediency Council, the ultimate arbiter of disputes between parliament and the 12-man Guardian Council until his death. Rafsanjani’s status gave him sufficient protection to remain a political player for nearly four decades.

The death of a major powerbroker shifted the internal political balance. Rafsanjani had been a voice for pragmatism and a supporter of President Hassan Rouhani. Reformers feared his death would negatively impact Iran’s presidential election in May—and be a boost to hardliners.

Anniversary of 1979 Revolution

Iran celebrated the 38th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution on February 10. Iranians held mass rallies across the country and the president addressed the nation. The Islamic Republic “won’t give in to bullying and threats,” Rouhani vowed. “Some newcomers have come to power in the U.S. and the region,” Rouhani said, alluding to the Trump administration. “They should know that Iranian nation must be talked to with respect.”

38th anniversary of the Islamic revolution today #Bahman22 pic.twitter.com/V3JO7UzFdi

— IranTalks (@IranTalks) February 10, 2017

But Anti-U.S. sentiment in Tehran was more subdued than in previous years. Many demonstrators condemned President Trump’s travel ban on citizens from Iran, Syria, Somalia, Sudan, Libya, and Yemen entering the United States for 90 days. But the burning of U.S. and Israeli flags and shouts of “Down with the U.S.A.” were not as prevalent. In the run-up to the Tehran march, Iranians on social media called on their fellow citizens—using the hashtag #LoveBeyondFlags—not to burn U.S. flags, but instead to thank American protesters for opposing the ban. No missiles were put on display either, so the overall tone of the march, though still anti-Western, was not as aggressive.

Iran celebrates the anniversary of its revolution with far less of the usual U.S. flag burning https://t.co/oKYmG3xQVD pic.twitter.com/1LjYIWpI1v

— New York Times World (@nytimesworld) February 10, 2017

Rouhani Reelected

Candidates began registering for Iran’s presidential election on April 11. A record number of individuals—almost 1,600 men and 137 women, a record--registered for the May election. Nine days later, the Guardian Council announced the names of six men cleared to run: incumbent Rouhani, First Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri, Mashhad cleric Ebrahim Raisi, Tehran Mayor Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, Expediency Council member Mostafa Mir-Salim, and former Vice President Mostafa Hashemitaba.

The economy was the primary issue in the campaign. Iranians were frustrated with unemployment, inflation and the gap between rich and poor. The nuclear deal had not yet yielded significant benefits for the average Iranian. In an April 2017 poll, nearly two thirds of respondents said the economy was either “somewhat” or “very bad.” Rouhani highlighted improvements made under his administration, but he faced heavy criticism from conservative candidates Raisi and Qalibaf. They promised to create at a least a million jobs annually if elected.

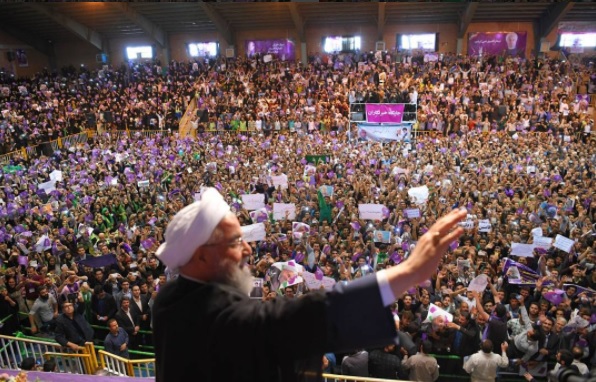

The campaign grew increasingly combative. Rouhani dared to rebuke rivals and even scolded hardline clerics and the powerful Revolutionary Guards. At campaign rallies and in television debates, he presented the election as a stark choice between freedom and suppression. He chastised other candidates for hypocrisy. “We’ve entered this election to tell those practicing violence and extremism that your era is over,” he said on May 8. “The people of Iran shall once again announce that they don’t approve of those who only called for executions and jail throughout the last 38 years.”

Four days before the vote, Qalibaf dropped out of the race and called on his supporters to back Raisi.

Four days before the vote, Qalibaf dropped out of the race and called on his supporters to back Raisi.

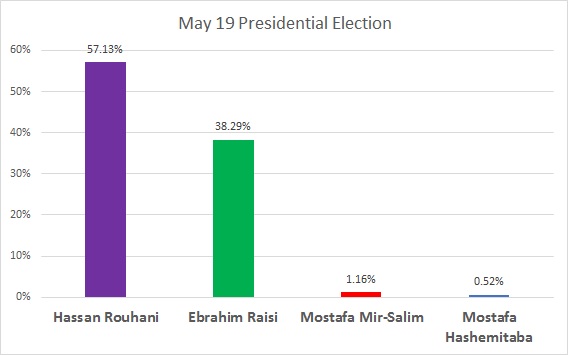

On May 20, Iran’s Interior Ministry announced that Rouhani won a second term by a wide margin—and better than for his first term. He garnered 57 percent of the vote, compared with 38 percent for his closest rival, hardliner Ebrahim Raisi. Rouhani’s victory was a significant blow to conservatives, who were seeking a comeback following a poor performance in the 2016 parliamentary elections. Rouhani won with the support of both reformists and centrists.

Rouhani thanked Iranians for reelecting him in a live television address. “The message of our people was expressed clearly in the election and today, the world knows well that the Iranian nation has chosen the path of interaction with the world, away from violence and extremism,” he said. Rouhani’s first two posts on Instagram after the election indicated his gratitude for support from Iran’s youth, who were key to his victory.

Trade and Economy

Iran’s economic growth significantly slowed in 2017 compared to the previous year. The IMF projected a real GDP growth rate of 3.5 percent for 2017, compared to 12.5 percent for 2016. Most economic growth was due to increased oil and gas sales. Non-oil industries only started to benefit from the improved business climate. The World Bank found that unemployment increased to 12.6 percent in Spring 2017, up from 12.4 percent six months earlier, despite growth in the non-oil sector.

Foreign investment in Iran has slowed for several reasons. U.S. and European sanctions for human rights abuses and support for extremist groups remain in place. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global enforcement body for anti-money laundering and combatting terrorism financing, still had concerns about Iran. Companies had to avoid violating complex sanctions, which could cost billions in fines and damage to their reputations.

Iran has not been an easy place to do business, even for locals. It ranked 124 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s 2018 “Doing Business” report, which evaluates procedures needed to start a business, get construction permits, register property, access credit, enforce contracts, trade across borders, etc. Investors have faced a climate rife with corruption in addition to bureaucratic red tape.

Despite these obstacles, Iran did manage to sign some valuable deals and secure billions of dollars in credit in 2017, mainly with European and Asian banks and companies. The following is a sampling:

- French PSA, the maker of Peugeot and Citroen, signed production deals worth $768 million with SAIPA and Iran Khodro (May 2017)

- Boeing and Iran Aseman reached a deal for the sale of 30 737s for $3 billion (June 2017)

- French energy company Total secured a contract worth $5 billion to finance and develop a gas venture in the South Pars Gas Field with Iranian and Chinese firms (July 2017)

- South Korea’s Export-Import Bank (KEXIM) committed to supply a $9.4 billion credit line to finance projects including a refinery in Isfahan and eight gas condensate refineries in Asalouyeh (August 2017)

- Iran established a $10 billion credit line with China’s CITIC Group to finance infrastructure projects in areas including water, energy and transportation (September 2017)

- Iran secured $3.5 billion and $10 billion in finance from German and Japanese companies, respectively, to be used for railroad projects (October 2017)

Many of the deals were related to land, sea or air transportation. The Islamic Republic has long had ambitions to become a regional transit hub. Iran’s acquisition of hundreds of new planes for domestic and international flights was key. In 2017, it began receiving aircrafts from Airbus and ATR. On January 11, Iran received an A321 jet, the first of dozens of aircraft ordered from France’s Airbus. Welcomed in a televised ceremony, it was the first new plane Iran Air had received in 23 years. For decades, international sanctions forced Iran to rely on old jets that became increasingly difficult to service and dangerous to fly. As part of the nuclear deal, sanctions relief allowed Iran to ink major deals with Airbus, Boeing and ATR.

Isn't that a beautiful #airplane in a beautiful livery? #IranAir #Homa #A321 pic.twitter.com/ztF6M4x8SY

— Iran Air (@IranAir_IRI) January 11, 2017

In December, Iran also inaugurated phase one of the Chabahar port. The strategically located southeastern port will enable Indian exports to Iran and landlocked Afghanistan to bypass Pakistan. It will compete with the Gwadar port, just 44 miles to the east in Pakistan. China has leased the port for 40 years.

Foreign Affairs

Syria

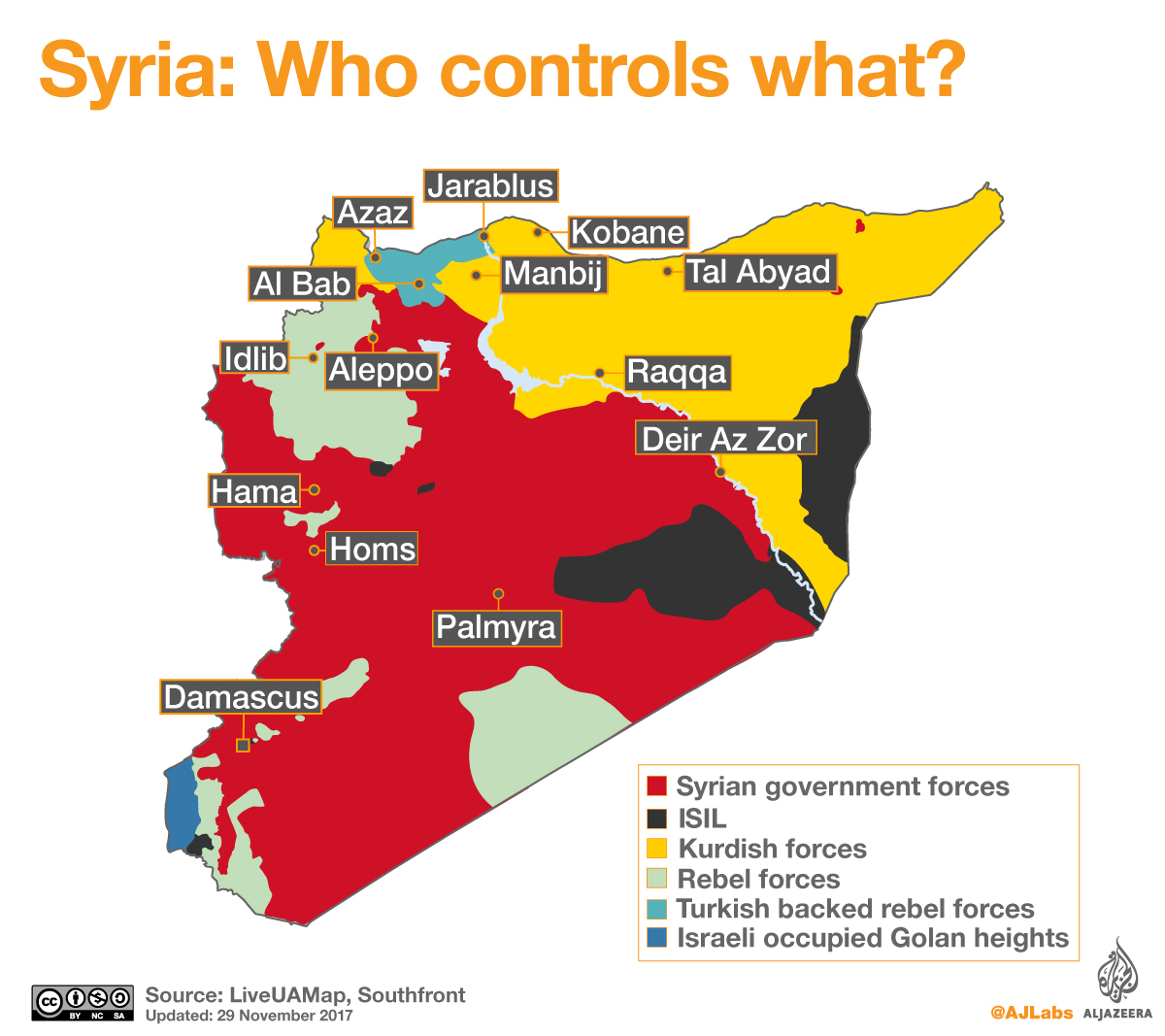

After the Syrian civil war erupted in 2011, Iran provided key military, logistical, technical and financial support—including military advisors—to the government of President Bashar Assad. Iran reportedly recruited thousands of Afghan and Pakistani Shiites to fight in Syria. Pro-regime forces retook a significant amount of territory from ISIS and rebel forces in 2017. In November, Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the IRGC’s Qods Force, reportedly planned and participated in the operation to take Abu Kamal, the last ISIS stronghold in Syria.

Major General #QasemSoleimani, the commander of Qods Force of #Iran's Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), in a surprise visit to #Syria's #AbuKamal. The #SyrianArmy and its allies are preparing to launch a major assault against #Daesh #terrorists in Abu Kamal soon. pic.twitter.com/sZiVkpPLSM

— Press TV (@PressTV) November 16, 2017

By late 2017, Bashar al Assad controlled more than 50 percent of the country, including its four largest cities, 10 of its 14 provincial capitals and its Mediterranean coast.

Gulf Crisis

On June 5, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Egypt cut diplomatic ties with Qatar in a coordinated move. They accused Qatar of destabilizing the region by supporting the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIS, al Qaeda, Iranian-backed groups in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, and Houthi rebels in Yemen. The bloc made thirteen demands of Doha; the first was to break military and political ties with Tehran.

Iran criticized Qatar’s neighbors for isolating the little sheikhdom. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain gave Qatari nationals two weeks to return home. They banned their citizens from travelling to Qatar. Saudi Arabia closed its land border with Qatar, through which the small country imported some 40 percent of its food.

Despite years of wide-ranging differences, Tehran-Doha relations deepened almost overnight. Iran dramatically increased shipments of foodstuffs to Qatar and allowed goods from other countries to flow through Iran to the isolated country.

Yemen and Tensions with Saudi Arabia

For years, Iran has been widely accused of backing the Houthis, a Zaydi Shiite movement that has been fighting Yemen’s Sunni-majority government since 2004. The Houthis took over the capital, Sanaa, in September 2014 and seized control over much of north Yemen by 2016, despite a military intervention led by Saudi Arabia.

Tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia escalated on November 4, when Yemen’s Houthi rebels fired a ballistic missile at King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh. Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al Jubeir told CNN that the kingdom considered the attack to be an act of war by Iran. Tehran denied involvement. In a tweet, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif countered that Saudi Arabia brought attacks on itself by its behavior.

Saudi Arabia intercepted another ballistic missile over southern Riyadh on December 19. The Houthis claimed responsibility for the attack, which targetedthe royal Yamama Palace in Riyadh. “As long as you continue to target Sanaa, we will strike Riyadh and Abu Dhabi,” rebel leader Abdul Malik al Houthi said. The Saudi-led coalition claimed the missile proved "continued involvement of Iran in supporting the Houthis.”

Yemen's Iran-backed Houthi rebels fire another ballistic missile into Saudi Arabia, Saudi government says, adding that the missile was successfully intercepted by Saudi air defenses. https://t.co/ONfqCANSqt pic.twitter.com/Oc5igOnOZC

— ABC News (@ABC) December 19, 2017

Lebanon

On November 4, Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri abruptly resigned, blaming Iran and its Lebanese proxy Hezbollah for destabilizing the region. The Arab world would “cut off the hands that wickedly extend to it [Iran],” he warned. Hariri, leader of the Future Movement Party, is the leader of Lebanon’s main Sunni Muslim political bloc and a close ally of Saudi Arabia. He announced his decision from Riyadh on the Saudi-owned Al Arabiya satellite television station.

Hariri claimed that outside powers, alluding to Iran, had stoked sectarian tensions and created a state-within-a-state through Hezbollah. Following Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, Iran sent some 1,500 Revolutionary Guards to the Bekaa Valley to help create, arm and fund a shadowy organization that eventually became Hezbollah, a militia and Lebanon’s foremost Shiite political party.

Hariri accused Hezbollah of gaining power by building a massive arsenal. Lebanon must have “only one state, one army, and one set of arms,” he said. The prime minister also claimed that there was a plot on his life. He said the current political climate resembled 2005, when his father and former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated. In 2011, four Hezbollah members were indicted by an international tribunal for the murder.

In November 2017, Lebanese officials accused Saudi Arabia of coercing Hariri into resigning. Iranian officials also alleged Saudi meddling. Hariri returned to Lebanon after visiting Abu Dhabi, France, Egypt and Cyprus only to rescind his resignation. He narrowly prevented a political crisis that could have collapsed the coalition government, which includes Hezbollah ministers and allies. Hezbollah and Iran appeared to be the winners at the expense of Saudi Arabia in the power struggle.

Warming Iran-Russia Ties

On March 27, Rouhani arrived in Moscow with a large political and economic delegation for a two-day visit. It was his first official visit to Moscow as president and his first foreign trip since the start of the new Persian year (March 20).

Iranian and Russian officials signed 14 memoranda of understanding to cooperate on a range of security, economic, scientific and cultural issues. Putin noted that bilateral trade had increased 70 percent compared to the previous year.

In a joint statement, Rouhani and President Vladimir Putin expressed support for the continued implementation of the Iran nuclear deal. They also criticized U.S. foreign policy by dismissing “unilateral sanctions” as “illegitimate,” likely a reference to U.S. sanctions on Iran for human rights abuses and support for terror and on Russia for its aggression on Ukraine.

On November 3, Putin visited Iran for the first time since 2015. In a meeting with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Putin voiced support for the nuclear deal and said that Russia objects to “any uniliteral change” to it. “We oppose linking Iran’s nuclear program with other issues, including defensive issues,” he said, apparently referring to President Trump’s criticism of the deal.

On November 3, Putin visited Iran for the first time since 2015. In a meeting with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Putin voiced support for the nuclear deal and said that Russia objects to “any uniliteral change” to it. “We oppose linking Iran’s nuclear program with other issues, including defensive issues,” he said, apparently referring to President Trump’s criticism of the deal.

Khamenei told Putin that enhanced Iran-Russia cooperation could help to isolate America and decrease its influence in the region. He proposed using national currencies in bilateral transactions to “nullify” the effect of U.S. sanctions. Putin and Iranian leaders also discussed Iran-Russia cooperation in supporting President Bashar al Assad in the Syria conflict. Putin said that the fight against terrorists there was going well.

The visit was timed to coincide with trilateral talks between Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan. They focused primarily on improving road and rail connections between the Caspian Sea nations. Eager to develop Iranian oil and gas fields, Russia agreed to collaborate on “strategic” energy deals that could involve up to $30 billion in investments.

Iran vs ISIS

On March 27, the Islamic State group released a rare Farsi-language video on social media that threatened Iran. The nearly 40-minute clip, by ISIS’s Diyala Province in neighboring Iraq, was titled “The Farsi Land: From Yesterday ‘till Today.” The Islamic State (also known as ISIS, ISIL or Daesh) accused Iran of being a repressive state that persecutes Sunnis while providing protection for Jews and cooperating with Israel and the United States. The clip expressed the organization’s goal to conquer Iran and return it to Sunni rule, as it had been in the past.

On June 7, ISIS gunmen and suicide bombers attacked Iran’s parliament and the mausoleum of late revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. At least 17 were killed and 52 were injured in the first attacks by any opposition group in Tehran in more than a decade.

Attack in Tehran appeared to be the first time that Iran has been successfully targeted by ISIS https://t.co/s97bknQBQ6 pic.twitter.com/Y48iSSt9Lp

— New York Times World (@nytimesworld) June 9, 2017

The six assailants who were killed were reportedly from western Iran. The woman who was captured was from southern Iran, according to Alaeddin Boroujerdi, chairman of Parliament’s National Security and Foreign Policy Committee. At least four of the attackers were reportedly from Paveh, a Sunni Kurdish town in Kermanshah province, western Iran. Serias Sadeghi, who was identified by the Intelligence Ministry, was a known ISIS recruiter.

Iranian leaders downplayed the significance of the attacks. Some lawmakers even took selfies as they waited for security forces to deal with the terrorists.

نمایی از داخل #مجلس#تهران pic.twitter.com/3mICD1nchz

— خبرگزاری تسنیم (@Tasnimnews_Fa) June 7, 2017

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said that “the fumbling with firecrackers in Tehran won’t affect the will of the nation.” Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani said the terrorists were cowards and that the attacks were a “minor issue.”

On June 18, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) fired six mid-range missiles from western Iran at ISIS targets in the Deir Ezzor region of eastern Syria. The IRGC said the missiles targeted a key arms depot, a military command center and the group’s Deir Ezzor headquarters. At least 50 ISIS members were killed, including several high-ranking commanders, according an initial IRGC report. A later statement claimed that 170 fighters were killed.

On November 21, Rouhani heralded the end of ISIS days after the group lost its last strongholds in Syria and Iraq. “Today, with God’s guidance and the resistance of people in the region, we can say that this evil has either been lifted from the head of the people or has been reduced,” he said. In his televised address, Rouhani accused Western countries, including the United States and Israel, of supporting the jihadi extremists. He criticized the Arab League for inaction on ISIS and the conflict in Yemen.

Human Rights

Iran’s human rights record did not significantly improve in 2017. In August, a report by the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Iran released concluded:

Information received continues to highlight serious human rights challenges in the country, including the arbitrary detention and prosecution of individuals for their legitimate exercise of a broad range of rights; the persecution of human rights defenders, journalists, students, trade union leaders and artists; a high level of executions, including of juvenile offenders; the use of torture and ill-treatment; widespread violations of the right to a fair trial and due process of law, especially before revolutionary courts; and a high level of discrimination against women and religious and ethnic minorities.

In October, Parliament did pass an amendment to the Law Against Drug Trafficking that could save thousands of prisoners on death row and dramatically reduce the number of executions per year. Iran has long been one of the world’s leaders in executions. In 2016, it executed 42 percent less people than the previous year, down from 977 to 567 recorded executions. It is still ranked number two, however, behind China and ahead of Saudi Arabia.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of The Iran Primer and The Islamists websites at the U.S. Institute of Peace.